Many urbanists had high hopes that Senate Bill 5466 guaranteeing denser transit-oriented development (TOD) near rapid transit would sail through the State Legislature after it cleared the State Senate and moved over to House. But amendments prompted by hesitant House Democrats gutted the bill, greatly pared back its scope and added a 20% affordable housing mandate on new buildings that appears to be a poison pill for actually encouraging housing. Lawmakers should strip that poison pill or the bill could end up being counterproductive.

Fortunately, amendments to House Bill 1110, which would remove prohibitions on fourplexes in the state’s largest cities, have been less drastic. The missing middle housing bill continues to worm its way through the senate and passing it would be a huge step forward for addressing the state’s housing crisis.

Governor Jay Inslee and top lawmakers pledged this would be the year of housing, responding to a clear consensus among voters that the state must ramp up housing production and ease restrictions on new housing. Those leaders promised a multifaceted approach that involved a “three-legged stool” of supply, subsidy, and stability. Without passing HB 1110, it’s hard to argue that the lawmakers followed through on their pledge.

Bills stabilizing rents fell by the wayside last month, meaning one leg of the stool has already been punted to next year. The state budget is still being hashed out, which means a marked increase in state subsidies for affordable housing could still be possible — though lawmakers have balked at Inslee’s four-billion-dollar bonding proposal, preferring a smaller package. Leaders have staked housing action on the supply bills and HB 1110 is the flagship of that effort. To chart a course to winding down the housing crisis, it’s essential they pass it.

The TOD bill could be a great complement to the middle housing bill if the poison pill is removed. The addition of a 20% affordability requirement for new housing in TOD areas might sound good on paper, but in practice, it’s likely to devastate housing production. If no housing is built, 20% inclusionary requirements mean nothing — 20% of zero is still zero.

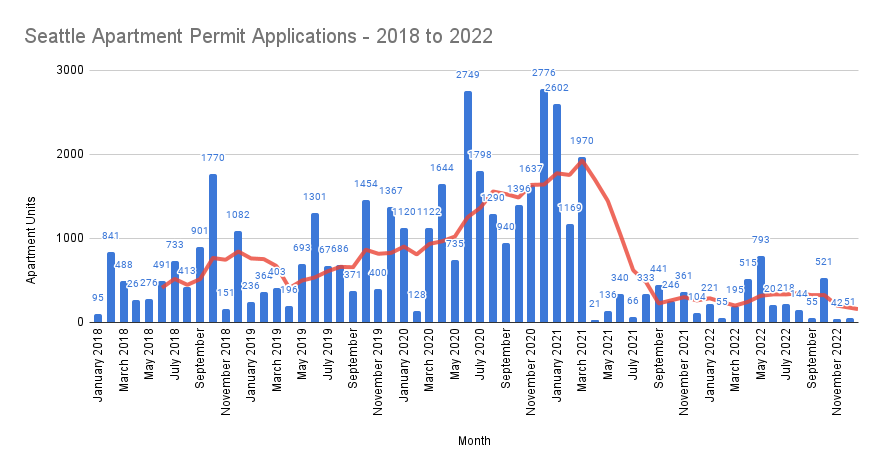

We are in a particularly difficult economic environment for homebuilders to weather additional costs and mandates. Interest rates are at a 15-year high, which means borrowing costs are very high for builders. Construction costs remain high after pandemic supply chain disruptions jacked up costs for building materials like lumber, steel, and concrete.

In Seattle, builders are also grappling with a strict new energy code, which, while great for environmental sustainability, adds considerable costs, especially at the initial phase when builders are still adjusting and tooling up. Design review and permitting times are slow and the City is also contemplating adding another cost in the form of a stricter tree ordinance. These combined headwinds already have slowed down permit applications and new housing starts, particularly after the stricter energy code went into effect in March 2021.

Seattle already has inclusionary zoning in the form of the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program that ranges from 3% to 11% requirement with rents set at 60% area median income (AMI) — which works out to $62,160 for a family of two in King County — or requires builders pay an in lieu fee aimed at creating an equal or greater amount of housing off-site. Several developers have complained that MHA has become a drag on development even at Seattle’s lower requirements. A 20% inclusionary requirement might turn off the spigot of market-rate development completely. Seattle tends to command some of the highest rents in the state, helping to offset inclusionary requirements. But cities with lower prevailing rents will struggle even more to shoulder affordability requirements.

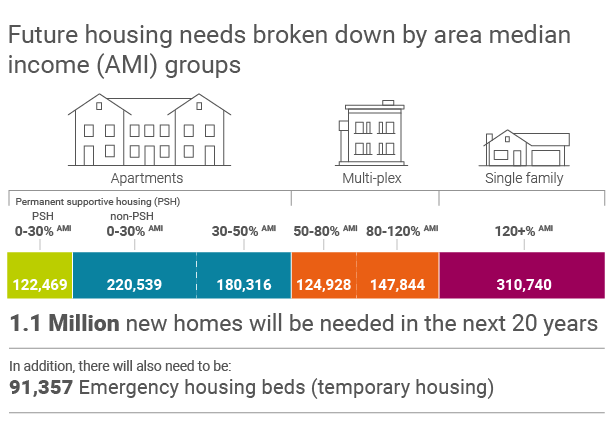

If the goal was to set aside TOD areas for affordable housing developers, that might sound good in theory. In practice the state hasn’t ensured enough subsidy to fund such an extensive level of nonprofit development. The Washington State Department of Commerce has estimated the state needs to add 1.1 million homes in the next two decades. At $300,000 per housing unit (actually building costs are likely higher than that now), 1.1 million homes would cost $330 billion to build. Like it or not, we’re going to need those market-rate developers to address our housing crisis.

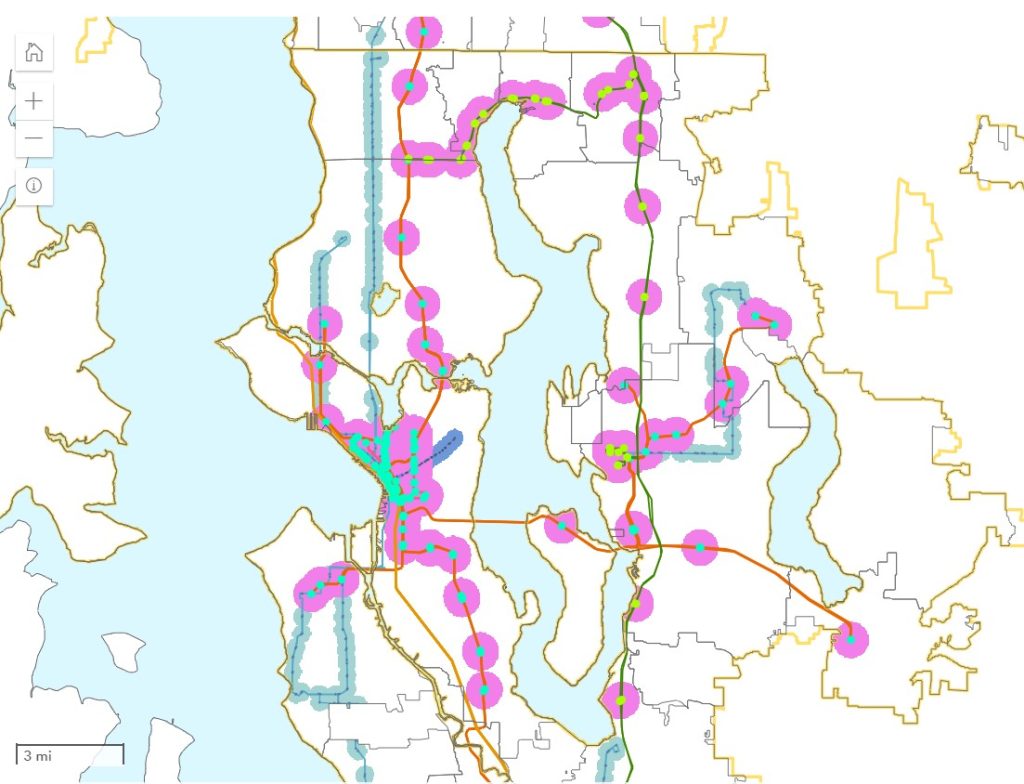

Taking out the poison pill of the 20% inclusionary requirement is essential because SB 5466 has been pared back to only the most transit rich areas where we really need to see housing. The backlash against the TOD bill appears to emerge from legislators not initially realizing what the bill entailed, even as the State Senate passed it comfortably in a 40-to-8 vote. The bill relies on floor area ratio (FAR) calculations, a somewhat esoteric relationship between total property area and the space in a building. It appears the FAR boosts in SB 5466 around frequent transit walksheds were more extensive than legislators realized.

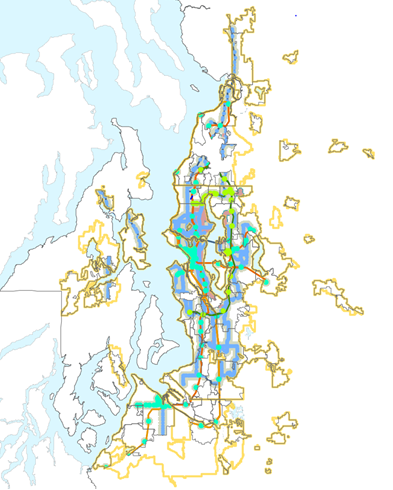

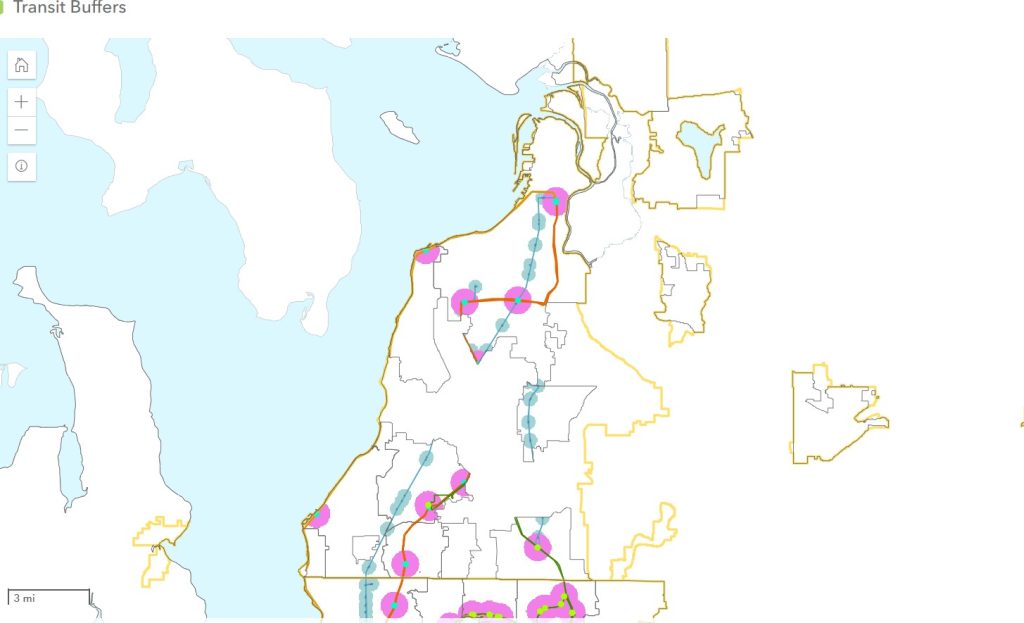

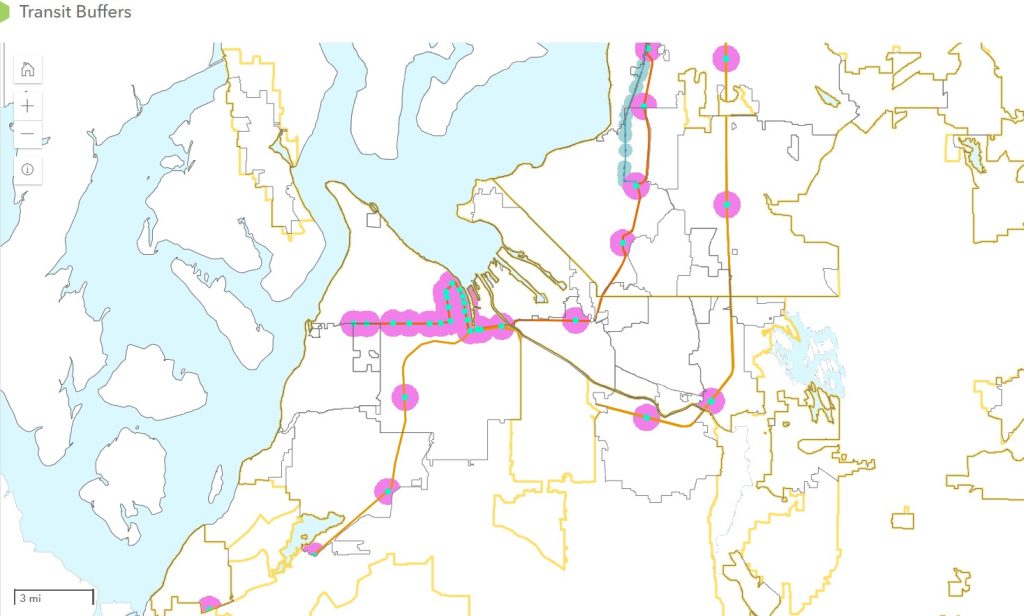

The Puget Sound Regional Council took a stab at demystifying the bill, with a map visualizing impacted areas but using “as the crow flies” radii circles that overestimate the extent of the walkshed. Leery legislators used that as ammunition to scale back the bill, pulling out bus stops that don’t serve bus rapid transit (BRT) lines and shrinking the major transit stop radii from 0.75 miles to 0.5 miles. They also reduced FAR requirements, going from the equivalent of eight-story buildings to just four-story ones.

“The scope of the bill was really large, and we also heard from a lot of our constituents, from a lot of our colleagues, that when we included not only light rail but bus rapid transit, and frequent bus stops, that the scope of redevelopment was a little unnerving for many,” Rep. Strom Peterson (D-LD21 Edmonds) said as way of explanation for the House’s scope reducing amendments.

Stripping out non-BRT grade bus service and reducing walkshed radii to a quarter-mile greatly scaled back the scope of the bill, as shown in the maps below which updated after that amendment entered the legislation. Halving the radius results in the area of the walkshed being cut by 75% due to power of squares in math. State lawmakers seem intent on defining King County’s Metro’s RapidRide lines and Community Transit’s Swift service as BRT. Little else qualifies, which is an indictment of how little our state invests in bus service.

We should invest far more in bus service, especially considering the premium that riders place on frequency, speed, and reliability. More Washingtonians should be able to live near BRT and rail service. That means expanding transit service, but it also means not putting undue burdens on adding housing near rapid transit we already have. SB 5466 should not pass until the 20% inclusionary requirement is removed and greater benefits to housing production are ensured.

Luckily, HB 1110 is still a very helpful bill. While fourplex zoning requirements are now focused on cities with populations of 75,000 residents or greater, that’s still a major swath of the urbanized portion of our state. Allowing multiplexes in exclusive single family zones doesn’t just increase housing production, it also expands access to desirable neighborhoods and reduces housing segregation, as Urban Institute research has shown.

Futurewise has a tool to email your legislators in support of their three priority bills and they also have a script to call your senators to urge them to support HB 1110. You can also sign in as pro on the HB 1110 legislation page.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.