There’s a saying that the path of progress doesn’t follow a straight line. This has certainly been what I’ve experienced in my two decades of working on Seattle housing policy. When it comes to solving Seattle’s housing crisis, I often see us take one step forward and two steps back.

Take, for instance, what’s happening this month. On the one hand, Olympia is taking a giant step forward with proposed middle-housing legislation that will allow a wide range of small-scale infill housing types throughout every city. Simultaneously, Seattle is considering new tree protection legislation that would significantly restrict infill development on lots throughout Seattle, especially in the exclusive single-family zones that the middle-housing bill is intended to open up.

The issues with the tree legislation are numerous. The city has opted for a heavy-handed approach that is all sticks and no carrots. Every tree larger than six inches in diameter will now be subject to new regulations. Every tree larger than 12 inches in diameter will get many of the restrictions currently reserved for truly exceptional trees, forcing any nearby building permits to produce a mountain of paperwork and undergo lengthy permit reviews. This process may not end up saving a lot of trees — the tree loss isn’t primarily coming from areas impacted by development – but it will ensure that every project wastes tens of thousands of dollars and months of permit review time to comply with all of the new documentation requirements. It is ironic that the proposal to save our tree canopy involves a forest worth of paperwork.

Seattle’s tree canopy coverage has indeed declined slightly over the past few years, mostly on public lands and in neighborhood residential zones. The area of lost canopy is cited as 255 acres, which at 40 trees per acre represents about 10,000 trees lost. The city of Seattle covers 53,620 acres, of which 28.1%, some 15,000 acres, hosts tree canopy.

The tree loss is not a huge problem, nor is it a difficult one to solve. People love trees. They are generally happy to plant them, care for them, and preserve them. A simple solution would focus on planting a lot of new trees and providing incentives for landowners to retain existing ones. Unfortunately, this new ordinance burdens every new development and every homeowner with page after page of new restrictions on the quiet enjoyment of their land. People accustomed to thinking that they have the discretion to take down a small tree that is not to their liking and re-plant with one that they prefer will be shocked to discover this is no longer their right.

Through its 48 pages of new rules, the legislation lacks the nuance and flexibility that it would contain if its crafting had included meaningful input from people that design and build housing. It contains none of the current rules that allow projects to remove trees if preservation prevents development to the zoned capacity of the site, which means that many sites that were previously developable will simply not work under the new rules. Maddeningly, the rules are so vague and subjective that many applicants will not discover the extent of the problem until they are months into their permit reviews.

The legislation does not just impact development. Homeowners will need a permit to remove any tree over 6 inches in diameter, a measurement made more complex if the tree forks low like many of our city’s beloved magnolia trees. The Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections will see a surge in applications for hazardous tree removal, which will be the only way to remove a tree outside of new development. Again, no carrots, all stick. And if the sticks are larger than 6 inches, a permit is required.

A lot of the conversation around this legislation has been framed as “trees versus housing”. This is not a particularly helpful framework since it’s not hard to have both. However, before you can craft a “both-and” strategy, you have to decide which issue takes priority. When you ask Seattle residents what the biggest challenges facing the city are, tree canopy preservation does not make the cut. Instead, residents cite public safety, housing affordability, and homelessness as their biggest concerns. While maintaining an ample tree canopy is a valid issue worthy of our attention, we should not be considering solutions that hamper our ability to address more significant and pressing problems – such as housing affordability and homelessness – that stem from a limited supply of homes.

Ever since the city started using terms like “housing affordability crisis”, policymakers have tried to address this problem at the zoning code level while simultaneously enacting policy after policy that add costs, time, restrictions, and inefficiencies into the design and construction process and undermining our housing goals. The tree legislation is just the latest in a long line of such missteps. Perhaps you’ve heard someone say that they’re “not opposed to density, just bad density”, and that they’d be happy to support new housing if only it would [insert wish list here]? Seattle’s approach to new housing falls along these lines. As soon as zoning changes open up a lane for more housing, Seattle leadership piles on a bunch of new requirements as if to say: I’m not opposed to new housing, just so long as it:

- Pays for affordable housing.

- Pays for the cost of climate change adaptation.

- Pays for our new infrastructure.

- Pays to make our sidewalks and curb ramps more accessible.

- Pays for more public outreach process.

- Pays for our future transportation improvements.

Affordable housing, climate adaptation, and infrastructure upgrades are important issues, However, these are general societal responsibilities that have been laid at the doorstep of every new unit of housing constructed in Seattle. Sticking it to new neighbors is a whole lot easier than asking the current public to pay for it. Unfortunately, each of these new mandates adds to the cost of new housing and the cumulative effect of this pile-on exacerbates our housing woes.

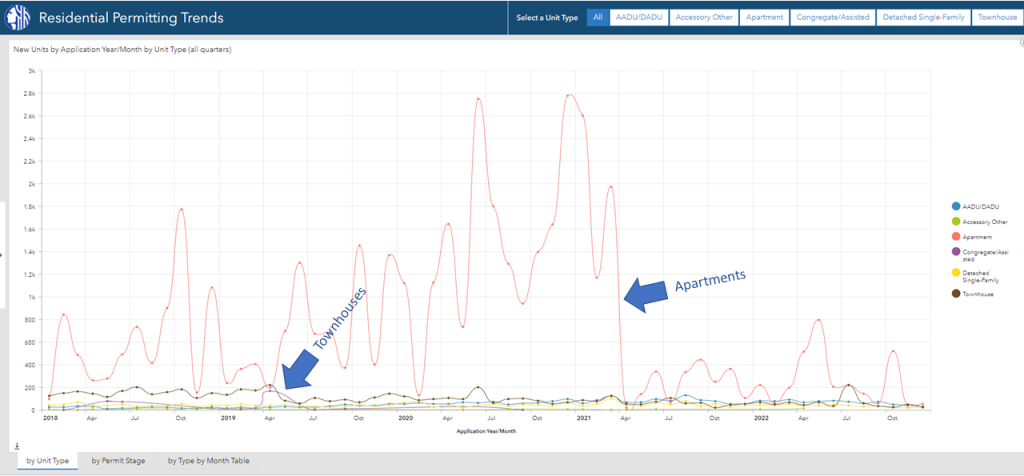

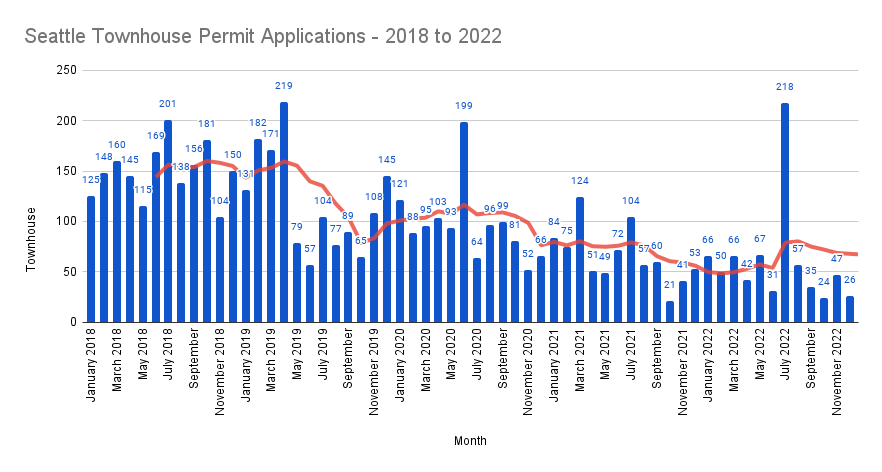

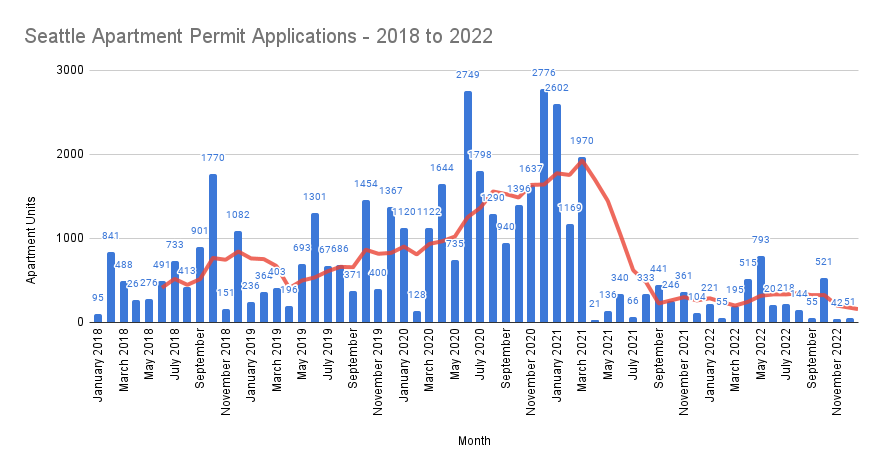

The cost inflation that comes from over-regulation mostly gets delivered as a death by a thousand cuts. But occasionally something really dramatic happens that lets us see the effect more clearly. Seattle recently launched a new housing dashboard that provides data on housing production over the last five years. If you study the graphs for residential permitting, you will see two dramatic change events.

- Applications for new townhomes dropped 50% after April 2019 after Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) fees for all new housing were introduced. MHA hit townhouse builders especially hard since the upzones didn’t provide any meaningful extra capacity for builders, but it did cost them $20,000-$30,000 per unit in fees. This has reduced permit applications by over 940 homes per year.

Applications for new apartments have dropped over 67% since March 2022 after a new energy code was introduced that radically changed the requirements for mechanical systems in multi-family buildings. Unlike previous code cycles where the changes were more incremental, this update was a quantum shift. The building industry does not yet have a way to respond to all of these new mandates in a cost-effective way, with the result being a $20,000 to $30,000 premium in the cost to build an apartment unit. This has contributed to permit applications dropping by over 8,000 homes per year.

Will the tree legislation create another huge downward spike in our housing production numbers? It’s likely to be another of the thousand cuts that each take their toll but are hard to see individually through the noise. It will probably exacerbate and strengthen the recent downward trends that we’ve seen, and will likely reduce the production numbers in Neighborhood Residential zones that we are hoping to encourage. In the end, suppression of housing leads to housing shortage, which leads to more expensive homes, higher rents, more struggles for people trying to become homeowners, and more renters getting priced-out and displaced. Ultimately, as these stressors filter down to our most vulnerable citizens, exacerbating our challenges with homelessness, social disorder, and public safety.

On the bright side, we’ll have generated a lot of great arborist reports to read at night for entertainment.

David Neiman

David Neiman, AIA is a partner at Neiman Taber Architects, an award-winning Seattle firm specializing in urban housing with a focus on issues of livability, affordability, community, and access to housing for all. Through a combination of innovative design, involvement in public policy, and development of his own projects, he has helped to pioneer new approaches to housing in Seattle and to shape the regulations that guide its development. A 4th generation Seattleite, he holds architecture degrees from the University of Washington and the University of Pennsylvania, and is a licensed architect in the state of Washington. He is a past member of the Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) Committee and chair of the NW Design Review Board.