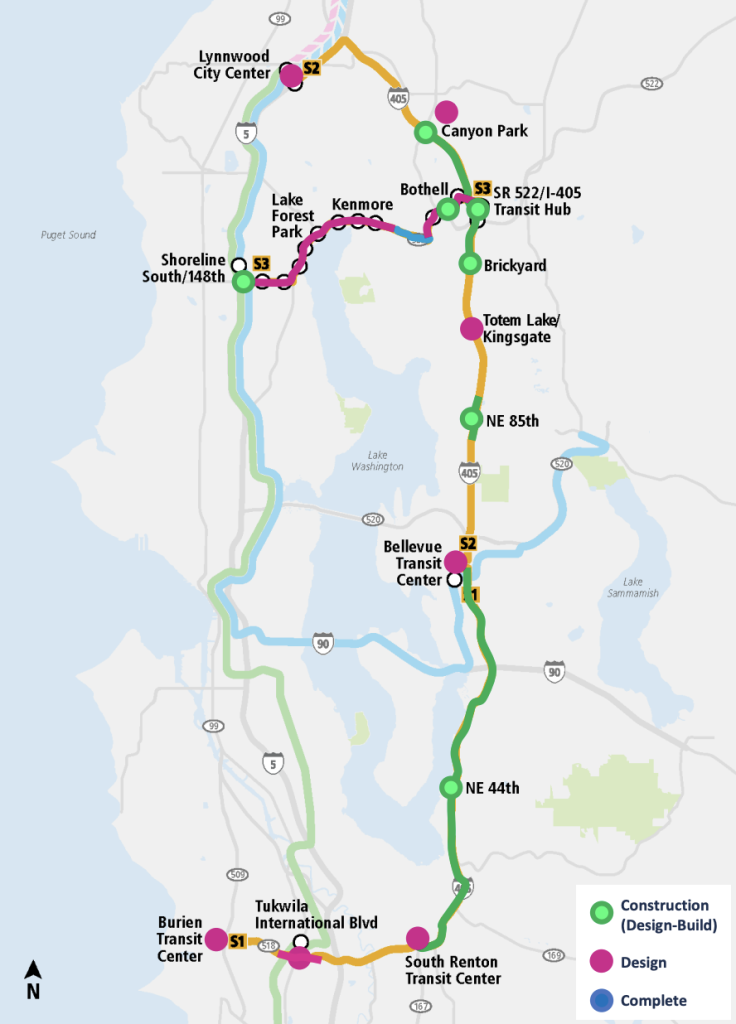

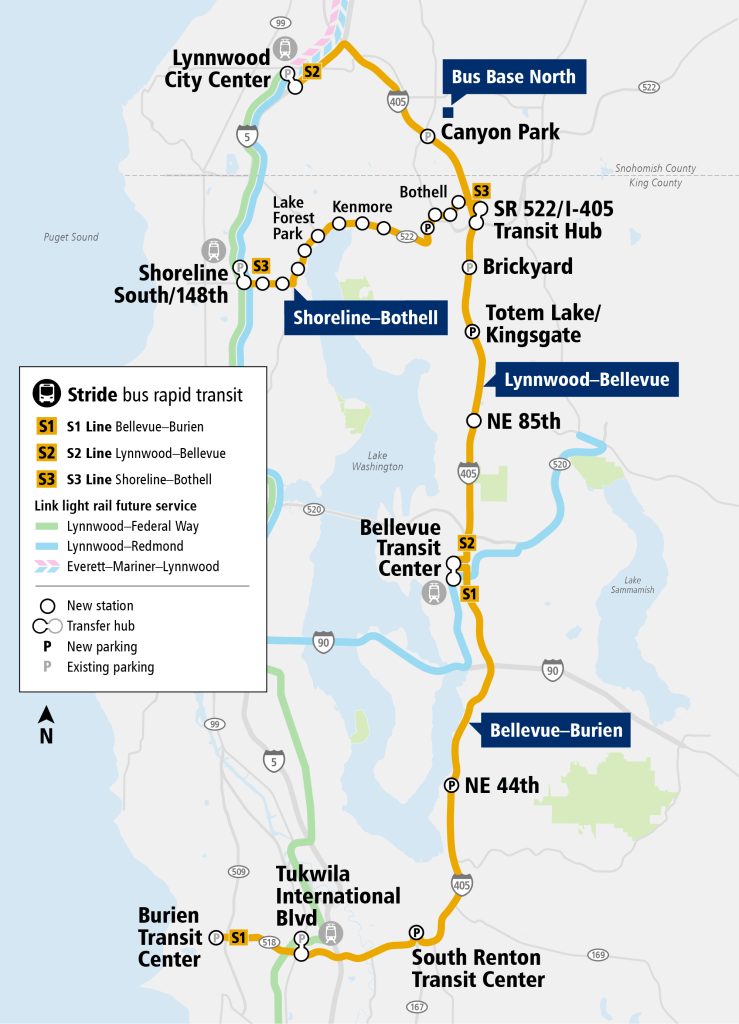

The much-delayed Stride bus rapid transit program continues to get more delayed. Generally speaking, the three projects — dubbed the S1, S2, and S3 Stride lines — are trending one to two years behind the 2021 realigned schedule and three to four years behind the original Sound Transit 3 plan, according to a recent update from Sound Transit. The earliest arriving project, serving the SR 522 corridor, is now tabbed for 2027, while the two I-405 projects are delayed to 2028.

“These potential delays reflect constraints in the construction industry and slower procurement timeframes,” program manager Bernard Van De Kamp said in April. “Currently, the issue is with design-build procurements that are going a little bit slower than we had anticipated.”

Despite the delays, the agency will be able to incrementally launch parts of the capital investment program for current bus service. New bus lanes between Kenmore and Bothell are an example of that.

In total, three Stride lines are set to launch in the next five years. The S1 Line will run primarily on I-405 from Burien to Bellevue (17 miles and five stops) by 2028. The S2 Line will similarly run mostly on I-405 from Lynnwood to Bellevue (20 miles and seven stops) by 2028. And the S3 Line will run mostly on SR 522 between Shoreline South/148th Station and I-405 (eight miles and 14 stops) by 2027.

In a report to the Sound Transit Rider Experience and Operations Committee, Van De Kamp highlighted some recent progress on the Stride lines.

For the S1 and S2 Lines, Van De Kamp said the agency has completed environmental remediation of the South Renton Transit Center and construction is underway on I-405 in Renton, including the NE 44th Street interchange modifications and freeway stop. Other aspects of the project are seeing advancement, including final design of transit centers and spot improvements reaching 60% to 90% design and issuance of a contract with a builder for the NE 85th Street interchange freeway stop in Kirkland. Sound Transit also plans to accept design-build proposals in June for the Brickyard, SR 522/I-405 interchange, and Canyon Park freeway stations.

As for the S3 Line, Sound Transit has completed construction of the Bothell-Kenmore business access and transit (BAT) lane on SR 522.

“We are pleased with completion of the first Stride construction project last summer,” Van De Kamp said. “These improvements are in use and are benefiting Sound Transit Express and King County Metro services today.” The agency has also been working on final design of the full project and engaging with community on plans.

A related piece to the lines is the new Bus Base North in Canyon Park. The facility will support the lines with operations, maintenance, and storage, of an all-electric bus fleet. Design has reached the 60% milestone and the agency is in the permitting process with City of Bothell. However, the agency has hinted at some worry that the sluggish pace of permitting on the City’s side could cause further delay to the project and revisions to the Canyon Park business park’s recorded covenants, conditions, and restrictions are an outstanding obstacle.

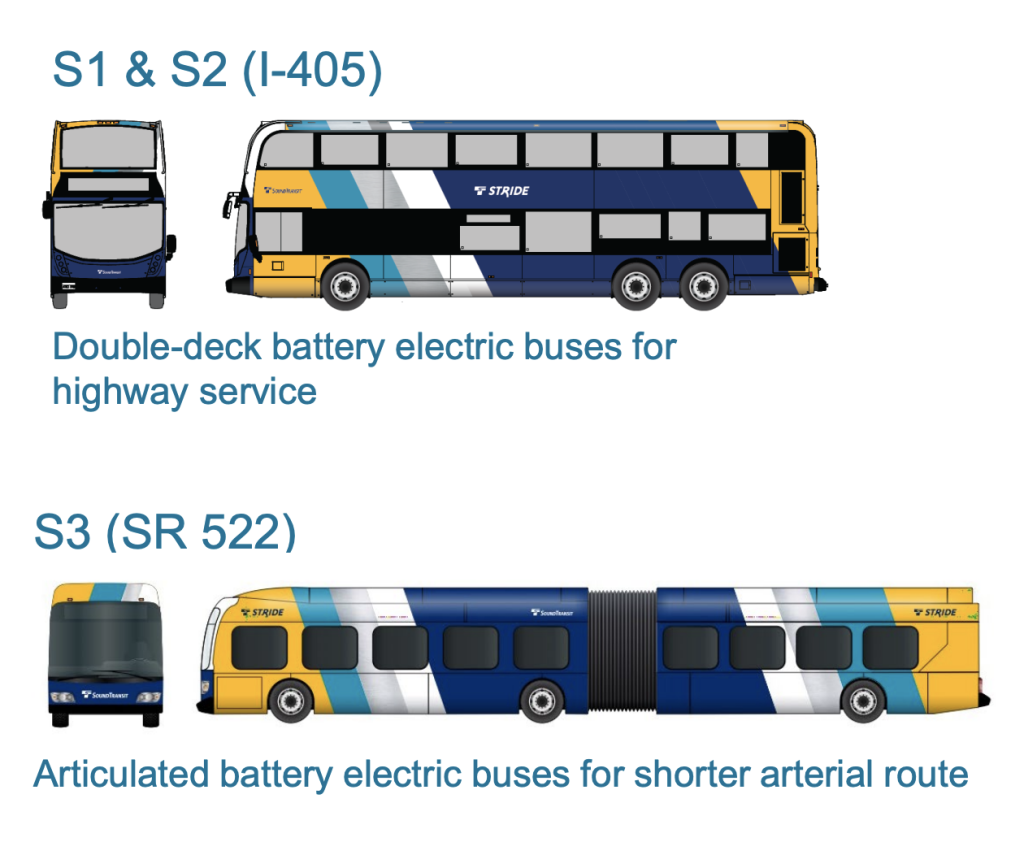

When the bus base opens, it will consist of an all-electric bus fleet using a mix of double-decker and 60-foot articulated battery-powered vehicles. The double-decker buses will serve the S1 and S2 Lines while the articulated buses serve the S3 Line.

Sound Transit plans to have electric-charging facilities in the field in addition to the bus base, Van De Kamp told the committee. Bus layovers and terminals may feature inductive charging equipment, which allows vehicles to roll over electrified pads that transmit electricity to vehicle batteries without any formal attachment. Charging in the field will certainly be important with such long bus routes since battery-powered bus technology is still in its infancy, not as reliable as other technologies, has short operating ranges, and take substantial amounts of time to charge up. Sound Transit plans to place purchase orders for the whole fleet later this year, but the agency needs to first finish developing procurement specifications.

A unique aspect to the bus base is that Sound Transit plans to operate it with control over a contracted service provider. The agency has traditionally relied on other public transit providers for storage, maintenance, and operations of buses. Sound Transit intends to put the contract out to bid this year and award the contract in 2024 — two years before the facility is expected to fully open.

The contractor will be responsible for fully staffing and operating the facility, including hiring and managing bus operators. Partner transit agencies will have the opportunity to bid for the contract but Sound Transit will be open to private contractors, too. The contractor may also have a hand in operating some of the agency’s ST Express bus service, which could help restore currently reduced or suspended service that partner transit agencies have not been able to deliver.

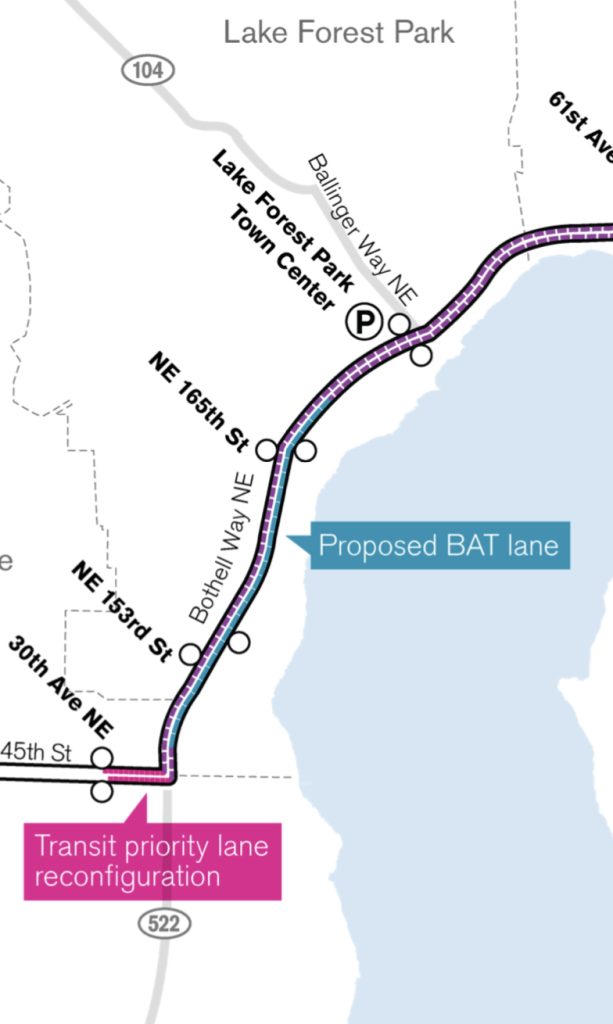

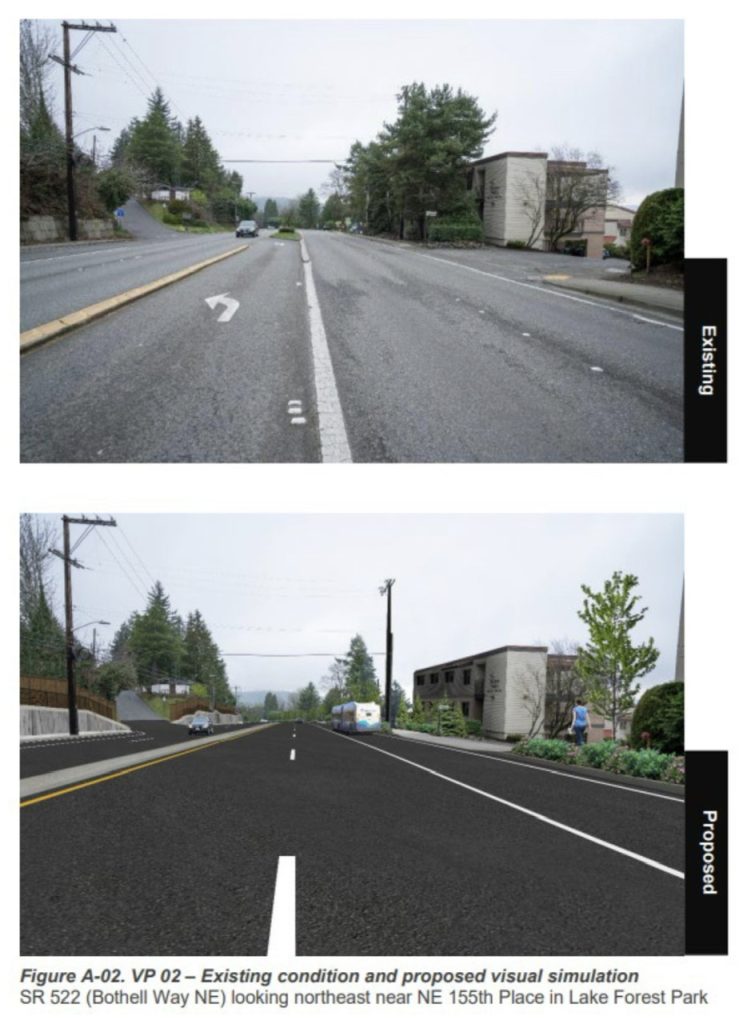

Ahead of the committee update, Sound Transit held open houses in March, which centered on 60% design materials for the S3 Line street improvements, including segments on NE 145th Street and in Lake Forest Park, Kenmore, and Bothell (SR 522, Downtown, and University of Washington). The agency hopes to reach 90% design as soon as June, but the project has stirred quite a bit of controversy in Lake Forest Park — a very wealthy enclave municipality — where some of the most useful investments are proposed.

Well-connected residents — some city councilmembers — have bombarded Sound Transit officials for months over proposed bus lanes through Lake Forest Park. The latest designs would shift some elements of SR 522 and expand it to accommodate a new northbound business access and transit (BAT) lane on a 1.2-mile stretch of the eight-mile corridor. It’s the highway expansion that has stirred up opposition since it would mean some removal of trees, taking of private property, and construction of new retaining walls.

In response, Lake Forest Park officials are pursuing special regulations for retaining walls when built as public infrastructure. That could complicate matters for Sound Transit. Draft legislation would give the city broad authority over design approval and calls for special architectural finishes with vegetation.

Sound Transit staff have raised several issues with the legislation. The agency says that native vine species that climb walls, like the retaining walls Sound Transit is considering, don’t exist in the Pacific Northwest. Substitutes like Boston Ivy or Carolina Creeper would be the closest option. The agency also says that growing vines from wall gaps isn’t compatible with the project and wall coverage goals should be targets rather than outright requirements.

Meanwhile, a group called “Citizens Organized to Rethink Expansion” or CORE have argued that Sound Transit should forego the highway expansion and instead focus on targeted speed and reliability techniques like queue jumps and transit signal priority. They claim that this would retain somewhere between 50% and 80% of the time savings over a BAT lane and save 490 trees from removal.

CORE has also claimed that the highway expansion could top $250 million, so not moving forward with it could save a substantial sum of money, though Sound Transit contends that the costs are closer to $102 million as of 2022.

However, the BAT lane is projected to save about 2.3 minutes on average and up to 10 minutes during the most congested periods. That cumulative time savings for thousands of daily riders could save several million minutes of travel time per year, as officials and leaders in Kenmore and Bothell (farther up the line) have noted. That’s not inconsequential and could help tip some people traveling the corridor toward transit and save valuable time for existing riders.

Something that Sound Transit has not seriously considered is simply taking a general purpose lane and rechannelizing the highway to fully achieve the project goals in Lake Forest Park. In November, Washington State Department of Transportation Secretary Roger Millar pondered as much during an agency meeting on the topic.

“What alternatives exist for Sound Transit? We’re building BAT lanes and widening the road to do that so that we provide that reliable and timely service,” Millar said. “An alternative would be taking an auto lane and converting it to a BAT lane. Another alternative would be running a very expensive regular bus versus [bus rapid transit]. Are there other alternatives out there aside from just refining the designs to mitigate impacts where we can but taking that land to have that BAT lane?”

At the time, Van De Kamp said that the agency hadn’t considered converting an existing highway lane to a BAT lane. He cited purported traffic impacts for not evaluating such an option and the importance of keeping the project closer to schedule.

Of course, Sound Transit is now facing down powerful individuals who may try to tie up the project in added costs, complexity, and delay. So it’s an open question if expanding the highway is really the optimal path forward for the project.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.