Often after Rosa Lopez picks up her son from school, they walk under a highway and half a mile to the South Park Community Center.

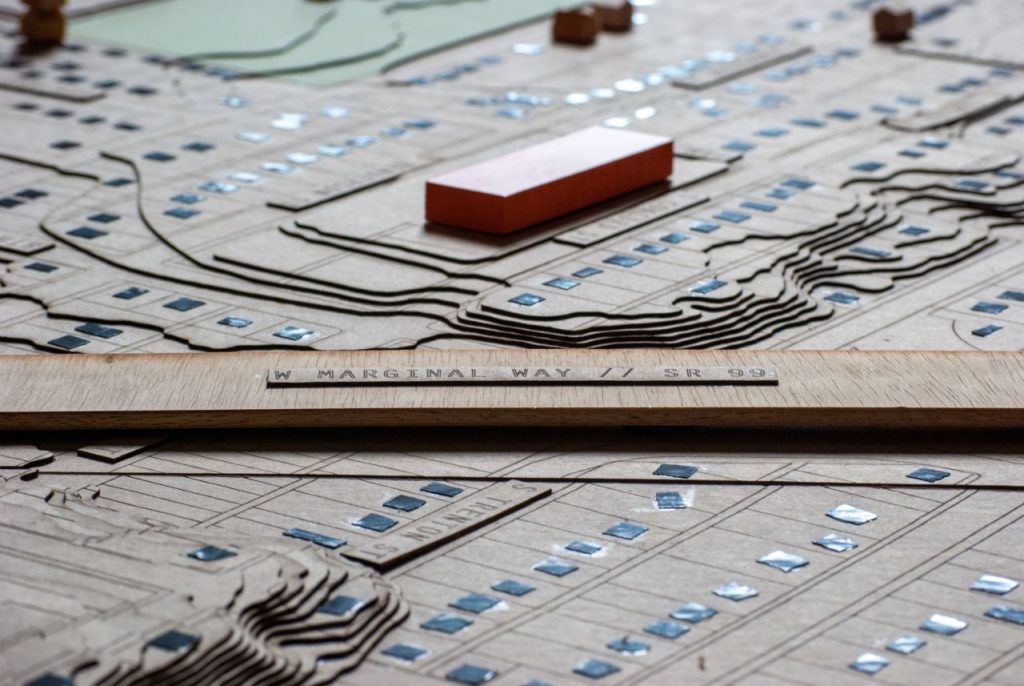

She pointed to their route on a wooden display of the western Duwamish Valley, a mapping tool designed by the University of Washington’s Department of Landscape Architecture. Twenty-two streets dead-ended into a plank that represents State Route 99. She lifted it to imagine what the future could look like.

“This idea to take down part of the highway can be justice,” said Lopez, who is one of the grassroots organizers for Reconnect South Park – a place-based movement to reclaim 44 acres for community uses like affordable housing, green space, and small businesses.

‘’We could have the same possibility to have health and clean air, like everybody else, that we deserve,” she said. “We do not deserve having the garbage station [South Transfer Station]. We do not deserve to have a contaminated river. And our kids play next to the freeway. We deserve a better life.”

Highways in South Park, also include nearby State Route 509 and Interstate 5, bring additional layers of emissions to the small neighborhood, which experiences an overburdening of environmental pollution. This year, the United States Department of Transportation awarded the City of Seattle and Reconnect South Park $1.6 million in federal funding to develop a plan that removes or restructures SR 99. The work is starting now through community gatherings like the open-house event that Lopez attended in May at the Georgetown Steam Plant.

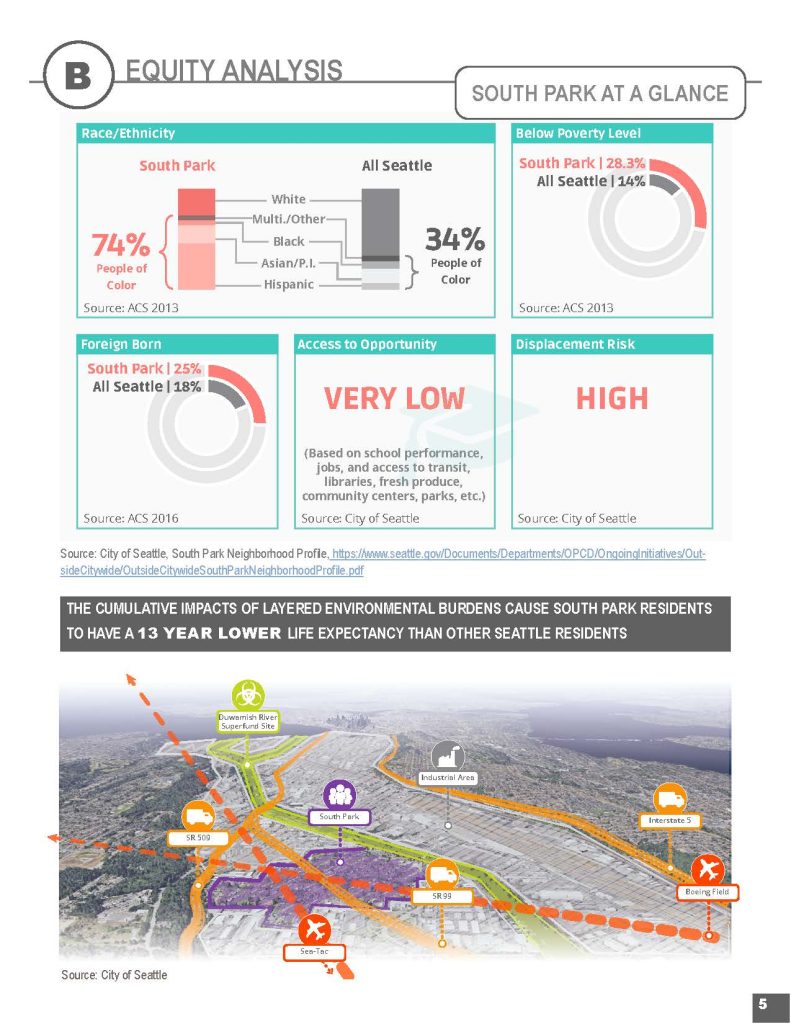

Reconnect South Park’s outreach is a core part of the planning process because they are building capacity for their culturally diverse community to contribute to the technical elements of the plan. Seventy-four percent of the neighborhood’s residents are Black, Indigenous, and Latino – a demographic who have been historically excluded from decision making because of systemic racism.

It’s why Lopez and Reconnect South Park organizers are not only talking with people on what the future could hold, but why the highway divided their neighborhood to begin with.

A legacy of displacement met by unyielding resistance

Injustice in the Duwamish Valley goes back to the mid-1800s when the U.S. government violated the Treaty of Point Elliott, taking land and rights from the Duwamish Tribe – who are still not federally recognized. South Park became a community of immigrants who farmed; people who were German, Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino, and who owned or tended the land. They sold produce in markets across Seattle.

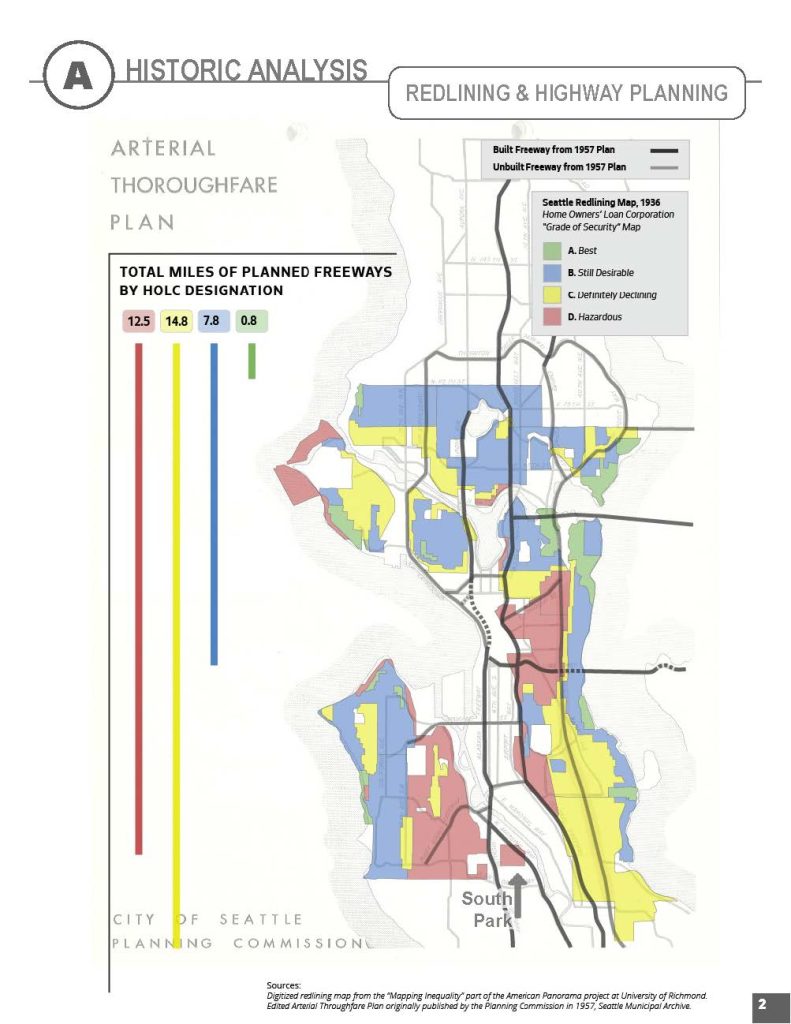

Over the decades, they organized to construct schools and to develop community services in their redlined community. Then displacement happened again under a presidential order that targeted Japanese Americans during World War II, removing 12% of South Park residents from their homes and moving them to internment camps. After the war, Japanese-American people made up only 1% of South Park. In place of the parcels of land they once used to farm came plans for a highway, according to the City of Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD).

Across the country, infrastructure planning and construction was underway through the Federal Highway Act of 1956, legislation from a generation of policymakers who were predominantly White men. SR 99 was initially a federal highway — US-99. Plans for it cut diagonally across South Park’s street grid without sidewalks.

When I-5 was completed in the 1960s, US-99 became obsolete. Many sections were eliminated, but the section in South Park remained. Around this same time, the local planning commission had converted the entirety of South Park and Georgetown for industrial use.

“The neighborhood fought back,” said Cayce James, the OPCD strategic advisor. “Perhaps it was because the urban planners intended to remove the neighborhood entirely and replace the area with industry that they made the decision to just plow through neighborhood streets like they did without working with the neighborhood fabric at all,” she said.

Their protests reverted the neighborhood back to residential zoning, but they could not stop the highway. As Black and Latino people began to move into South Park, state leaders claimed realigning the highway would be too expensive. They added a single pedestrian bridge that residents still rely on to this day.

Traffic makes up nearly a quarter of South Park pollution

Within one mile of SR 99 in South Park are two other freeways: SR-509 and I-5.

With its proximity to industry and port terminals, diesel trucks endlessly drive in the neighborhood releasing black carbon in their wake. These trucks emit as much as 400 times more particulates than gas vehicles.

Such air pollution can loft as far as a mile away from roadways, but the closer people are to the source, the worse it can be for their health — with adverse outcomes including asthma, behavioral problems, and slow brain development for children. In South Park, the elementary school, library, playfield, and skatepark are directly along SR 99.

This traffic-related air pollution from gas vehicles accounts for 28% of fine particulate matter in South Park. Diesel makes up another 21%. Diesel from trucks, planes, trains, and other freight and industry-related activity has the most cancer risks of all pollution in the area, according to the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency.

For Christian Poulsen, policy analyst for the Duwamish River Community Coalition, rethinking infrastructure is just part of the solution, because now these emissions mix with other pollutants like wildfire smoke in summer months. Policy and new funding sources — such as revenue generated from the state’s new cap-and-invest under the Climate Commitment Act — could support the electrification of fossil-fuel reliant trucks.

Right now, Poulsen is pushing for a cumulative air toxics law that would center environmental justice and prioritize human health while creating a robust, comprehensive, regional air quality monitoring network.

“We have all this data, but the way that you group datasets can obscure the true story,” Poulsen said. “Our air quality is something closer to Houston in South Park than it is the rest of Seattle. What we need to do is figure out the reality of air quality here and then regulate based on that reality.”

Poulsen published an op-ed with The Urbanist that calls on local regulators to live up to their rhetoric about progressive environmental and health policies. While King County Council has declared racism a public health crisis, renewed leases with polluting facilities and slow-moving initiatives like social justice plans have not delivered on their promises.

With a life expectancy 13 years lower than other neighborhoods in Seattle, people need protection, like better public health services immediately, because dismantling something like a highway takes time.

The feasibility of changing SR 99

OCPD and Reconnect South Park contracted with a consultant to conduct a technical analysis that would identify both beneficial and harmful outcomes from highway removal or redesign. That report may not be available until 2025.

The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) does not have a position on the study, citing that OPCD is managing the research.

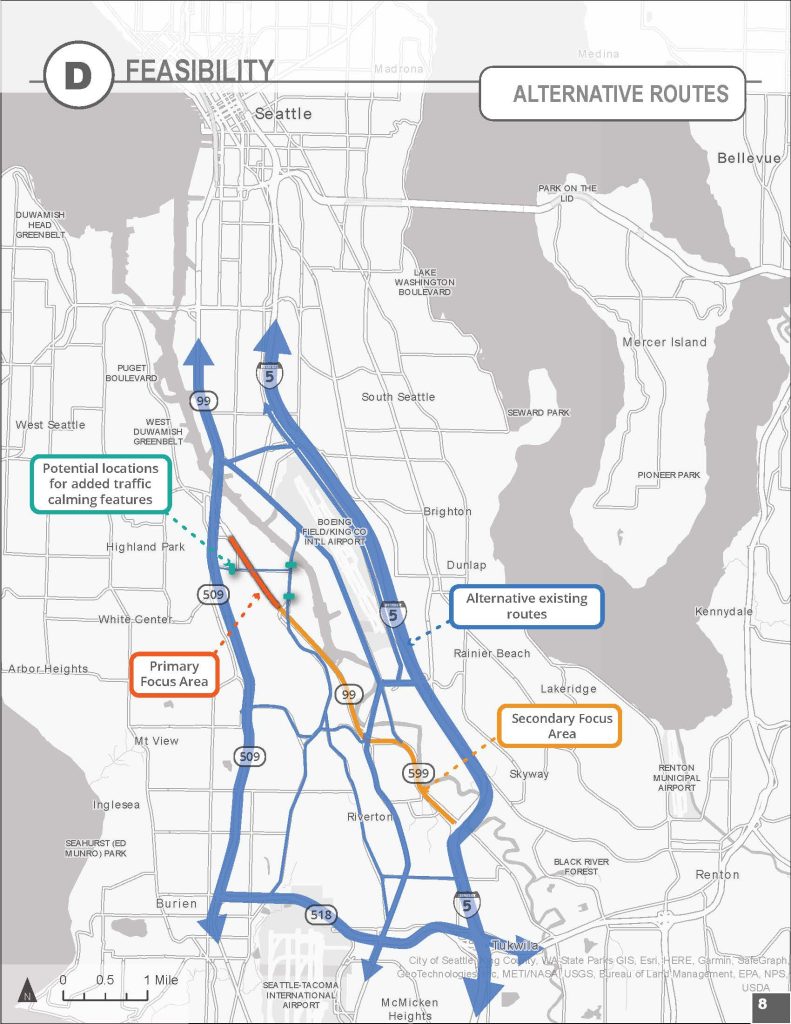

Preliminary analysis from OPCD supports the feasibility of removal because of relatively low volumes of vehicles on SR-99. Pre-pandemic traffic data shows that about 33,000 vehicles drove on SR-99 compared to 65,000 on SR-509 and 218,000 on I-5, according to traffic volume data from WSDOT.

Additionally, the state’s planned expansion of SR 509 via the Puget Sound Gateway project could absorb more traffic from SR 99 — albeit funneling it to neighboring communities. OCPD also points to a segment of SR 99 in Tukwila that was successfully decommissioned in the 1990s. Once it was ceded to the the City of Tukwila, urban planners there planted trees and added sidewalks along it. The state funded Puget Sound Gateway highway expansion in the 2015 Connecting Washington highway bill and topped it up in the 2022 Move Ahead Washington package, but didn’t fund or countenance highway removal in those bills.

Radical reimagining for the future

SR 99 removal could free up 44 acres of land that could respond to the need for community connection and climate change. In Seattle, South Park is among the neighborhoods most vulnerable to sea level rise; rather than perpetuate the history of extreme displacement, this new greenbelt could offer affordable housing for people who call this neighborhood their home.

But many approaches are possible for what could become a community land trust. It’s why Maria Ramirez, who is the Reconnect South Park project manager and Duwamish Valley Affordable Housing Coalition chair, believes strongly in hosting workshops that unpack what radical transformation looks like.

“We are trying to give the community capacity, and for them to realize they have power, and they have a say,” Ramirez said. “What we’re trying to do is make sure that the ideas for the vision bubbles up from the people.”

When the technical reports become available, the information will help Ramirez and her community make a stronger case for solutions that they believe work now and for future generations.

Ashli Blow

Ashli Blow is a Seattle-based freelance writer who talks with people — in places from urban watersheds to remote wildernesses — about the environment around them. She’s been working in journalism and strategic communications for nearly 10 years and is a graduate student at the University of Washington, studying climate policy.