Kitsap County’s largest city, Bremerton, is moving forward with a transportation project that has the potential to catalyze momentum for improved walking and biking infrastructure as the city plans to add 20,000 residents — a 44% increase — over the next two decades. Upgrading the Warren Avenue Bridge to better accommodate people who walk, bike, and roll is seen by cycling and safe streets advocates throughout Bremerton as a centerpiece project, and one that until recently might turn into a huge missed opportunity.

The current Warren Avenue Bridge offers less than the bare minimum for people outside of cars: a three-and-a-half foot path on either side of the bridge, below Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) standard, greets anyone trying to get across the four lane highway bridge, which is a segment of State Route 303. In 2022, the state legislature included $25 million for upgrades to that pathway as part of the Move Ahead Washington transportation package. Paired with another state grant of $1.5 million, the City of Bremerton underwent a monthslong process to determine the best design.

The benefits of upgrading the bridge so that it’s a reasonable choice for people walking or biking are substantial.

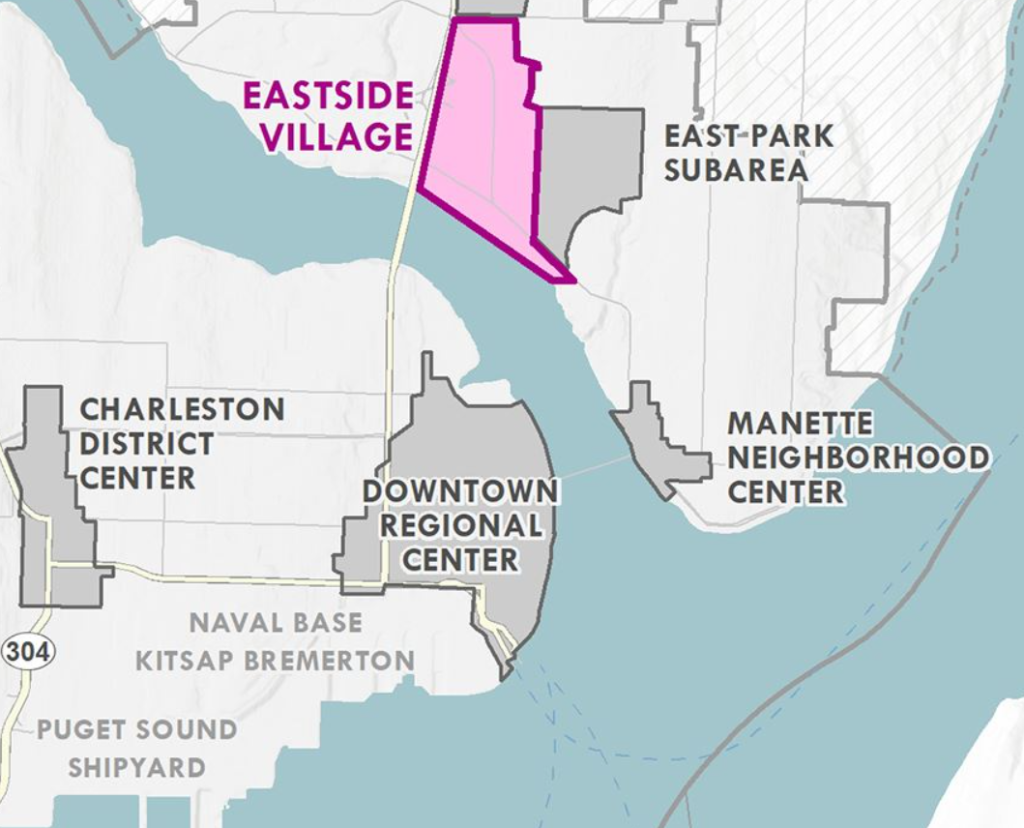

“Getting this northwest connector across the water, all of a sudden you open up bike access to downtown, [for] everyone who lives north of the bridge going all the way up to the county,” Bremerton Councilmember Jeff Couglin, who represents a district that touches the south end of the Warren Avenue Bridge, told The Urbanist. “We’re already seeing a ton of housing projects go in north of the bridge: the old Harrison Hospital area, which is now being called Eastside Village…very likely that’s going to be all small business and multifamily development.”

Coughlin has become somewhat of a steward for the Warren Avenue project over recent months.

Through the process to whittle down alternatives for the bridge, run by staff in Bremerton Mayor Greg Wheeler’s administration, a key point of contention was whether the city should move forward with a bridge design that includes paths with differing widths on the east and west sides of the bridge. The east side of the bridge is expected to be much more highly trafficked, especially by people on bikes. That side of the bridge makes the most sense to tie into the rest of the city’s bike network, with underutilized Rota Vista Park on the bridge’s south end an obvious place for a tie-in between the bridge and the city’s street grid.

The connections on either side of the bridge are nearly as important as the changes to the bridge itself, with a strong potential for more state and federal funding to be able to piggyback on the Warren Avenue Bridge grant to improve those connections. Along with upgraded trails to either end, there’s also a concept for a pedestrian underpass at the south end of the bridge connecting to Olympic College, which would make a wider east side of the bridge even more attractive to people on bikes.

Advocates for a wider east side bridge focused on the issue of safety for all road users.

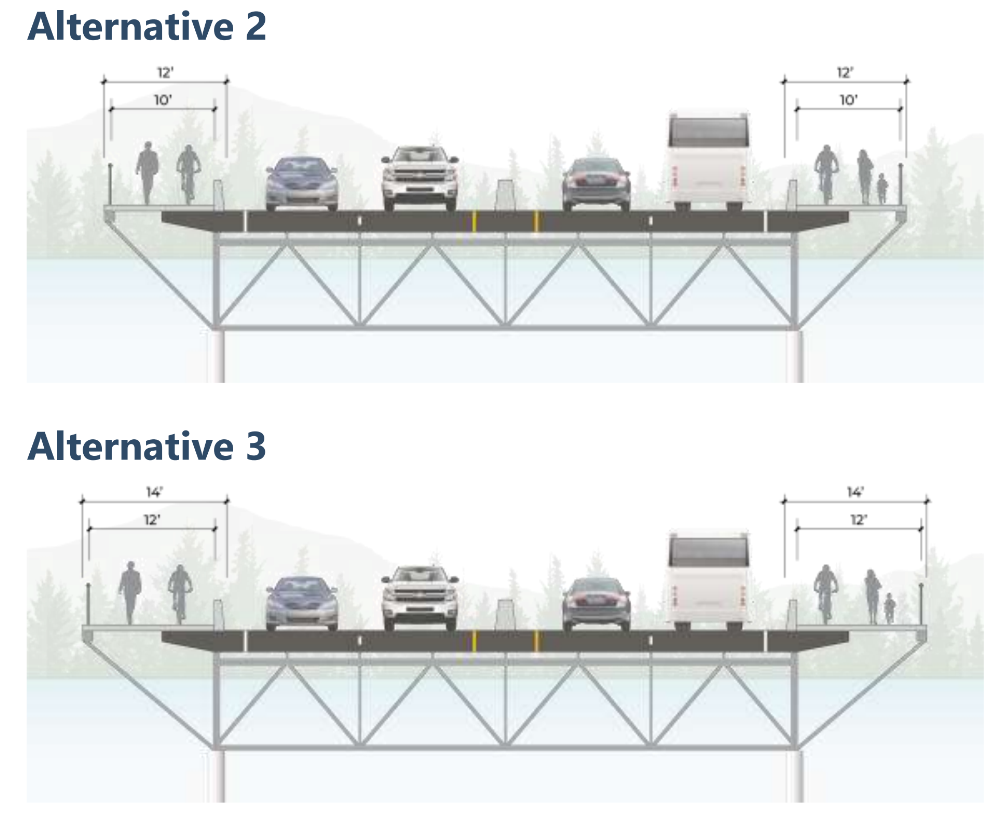

“The bridge has an infrastructure that serves not only Bremerton but unincorporated Kitsap County…and so what is the safest bridge for us to advocate for? It’s one with at least one side is 12 feet,” Dianne Iverson, who represents West Sound Cycling Club on the Warren Avenue Bridge stakeholders committee, told The Urbanist. “It’s not the bikes, it’s the walkers,” she said. The two foot difference between 12 and 10 feet, Iverson explained, is the difference between people having room to get around parents pushing kids in strollers and not.

Bremerton City Council Chooses Its Own Path

Despite the calls from bike advocates like members of the West Sound Cycling Club for a wider east side path, the options that ended up advanced to the Bremerton city council didn’t include that option. Instead, they were presented with an option for two ten-foot paths, which fits the project budget at $25.6 million, or two twelve-foot paths, which exceeds it at $29.1 million. But it was Council President Coughlin who had to be the one to introduce an alternative that included an eight-foot path on the west side of the bridge, with 12 feet on the other: an option within the project budget that would provide the most space for people of all modes to mix.

In discarding an option with a wider east side path, the Wheeler administration leaned heavily on two things: a public survey from this past April in which 65% of respondents said they preferred “equal width walkways on both sides accommodating pedestrians and bicycles”, and a unanimous vote from Bremerton’s ADA committee against only upgrading one side of the bridge to 5 feet, the minimum needed for ADA compliance.

But community members were left feeling that the Mayor’s staff had steered the public toward the outcome they wanted. “We were unaware that the cycling community had proposed keeping the majority of cyclists on a 12’ or 14’ east side route,” Jane Rebelowski, a member of the ADA committee, wrote to the Mayor and Council last week. “I believe if we had all the information our vote may have been different.”

“The administration put their foot on the scale, heavy, early on in this process,” Coughlin said ahead of the final vote last Wednesday. “At least three separate public meetings, the Public Works director said that his preference was to have equal with both sides. He made it very clear that that was his preference, and this is before any public comments were collected, or we heard from the public.”

Even still, several councilmembers were wary of advancing an option that didn’t have an official cost estimate, and hadn’t been directly vetted through the public process. “This has not gone through the process of going through a study session,” Councilmember Jennifer Chamberlin, who voted against moving forward with the 8- and 12-foot option, said. “And now we’re at the point where our administration has gone through all this work to get all this funding, done all this work to get this recommendation, and here we are beleaguering this,” she said. “I just have faith that we’re gonna have a beautiful product, with the 10 by 10 [feet on each side], that we need to get this out the gate, we need to get it moving.”

But ultimately there were four votes to move ahead with the 8- and 12-foot option, compared to two votes opposed, with one councilmember abstaining. “Let’s build for what we want to be. And I think this decision is going to send a message either way around what our priorities are for multimodal transportation in Bremerton,” Councilmember Denise Frey said ahead of voting yes. “If we don’t do this, we’re behind the curve, and that bridge is built, and it’s another 50 years or so until we get to do something different. I don’t want to make that mistake.”

Timing is a big issue, however. This year’s state transportation budget currently schedules funding for the Warren Avenue Bridge until 2029 or later. City officials are hopeful that if they get the project fully designed, the legislature will accelerate that timeline within the next few legislative sessions. In the meantime, there’s nothing stopping Bremerton from looking for additional funding to pay to improve the connections to either end of the bridge.

Forward Momentum on Bremerton’s Citywide Bike Network

Improvements to the Warren Avenue Bridge wouldn’t nearly be as meaningful if the City of Bremerton, along with Kitsap County, weren’t taking steps to improve the citywide bike network around Bremerton. Despite the fact that Bremerton has had an adopted non-motorized facilities plan since 2007, it’s only in recent years that the city has started in earnest to upgrade existing bike facilities and create new ones. In 2022, Bremerton added the first stretch of protected bike lane in Kitsap County, to Washington Avenue near the downtown ferry terminal.

Most of the new bike facilities improvements in Bremerton, however, are taking the form of paint-only bike lanes. Last year, the city completed upgrades to existing bike lanes on Kitsap Way, a big step for the SR 310 corridor. The new lanes provide more space for people on bikes, and connect through intersections where the old ones didn’t. But they still don’t provide physical separation for riders on the street, which has a 35 mph speed limit.

Next, Bremerton is moving forward with creating space for bike lanes on Naval Avenue, currently way overbuilt for the number of vehicles using the street. A growing subset of bike advocates in Bremerton are pushing for more physical separation, which would entice more reluctant cyclists onto the roads.

“I think in Bremerton at the moment for existing roads, we only have so much space to work with,” Coughlin said. “To me, the plastic bollards are a good step to have some sort of visual physical barrier there for cars and bikes…I think we’ll get there eventually.”

With upgrades to the Warren Avenue Bridge moving forward, the momentum is definitely there.

Correction: An earlier version of this article overstated the level of growth envisioned in Bremerton’s Comprehensive Plan. The plan envisions adding 20,000 residents or a 44% increase by 2044, which is well short of doubling the city’s current population.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.