One would be excused for missing the door to 911 Pine Street. It is a classic alcove doorway, deserving of little attention even if it wasn’t overshadowed. Unlike its neighbor at 901 Pine, it does not have a box office, lengths of velvet rope, and a giant marquee of flashing lights featuring the name of a popular Broadway show. More than likely, that show is the reason you’re standing on this block.

Inside the limited access door at 911 Pine is an elevator lobby. Trimmed in carved, fluted columns and mosaic marble tiles, it begs for fedoras and doormen. The narrow double elevators sit below embedded analog clock faces showing the car’s current floor. The one-time mail alcove and concierge station is now a welcome desk with security monitors. The closest thing to a bellhop is Stanley, the distinguished elderly Basset Hound and office pooch. There are patches of discolored repairs in the ceiling and wireboxes for electronics.

What is now the offices for Seattle Theatre Group and several other arts organizations was once an apartment building attached to the front of Seattle’s Paramount Theatre. It has the same fundamental allure as the venue, but unpolished and unpreened for the public. Like the building’s entrance, the apartments’ history is attached to the theater, but unseen in the glare.

Together But Separate

For over 40 years, David Allen has worked on the operations of the Seattle Theatre Group, the non-profit ownership of the Paramount, Moore, and Neptune theatres. Allen has stepped away from his long time chief operating role to hold the mantle of special projects manager. It allows him to “pay special attention to these historic buildings,” as he puts it.

Allen said the original builders envisioned the 48 residences as living spaces for the artists who would be performing in the attached theater. These roughly 32,000 square feet of units across seven floors were the city’s original live/work artist lofts. The apartments opened with the theatre in 1928.

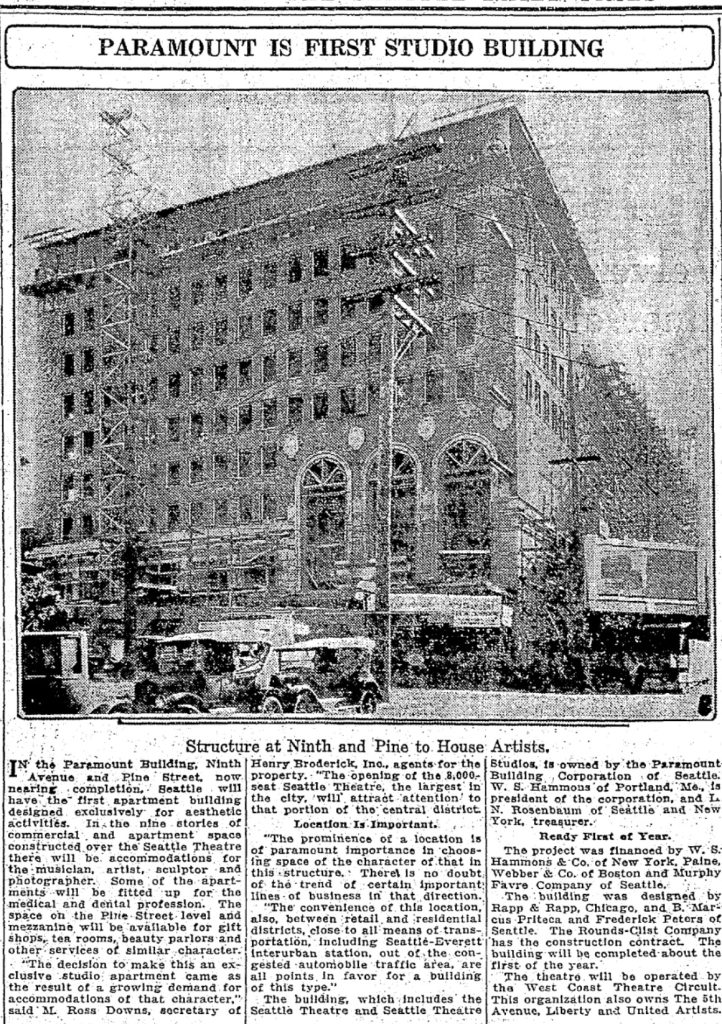

Newspaper accounts from the time of opening the ornate new building touted the possibilities for having the creatives so close to the venue.

“In the Paramount Building, Ninth Avenue and Pine Street, now nearing completion, Seattle will have the first apartment building designed exclusively for aesthetic activities,” the Seattle Daily Times announced in an article on October 23, 1927. “In the nine stories of commercial and apartment space constructed over the Seattle Theatre there will be accommodations for the musician, artist, sculptor and photographer.”

For the next 20 years, the building shows up in the apartment listings. “Delightful, modern apartments. Clean, classy, fine view, inviting rates.” No specifics are given on those rates. One can presume the nearby ads for $40 per month are comparable. Somewhat less than the Paramount’s neighbor, Premiere on Pine, which is currently offering a 1 bed/1bath apartment for $2450 per month.

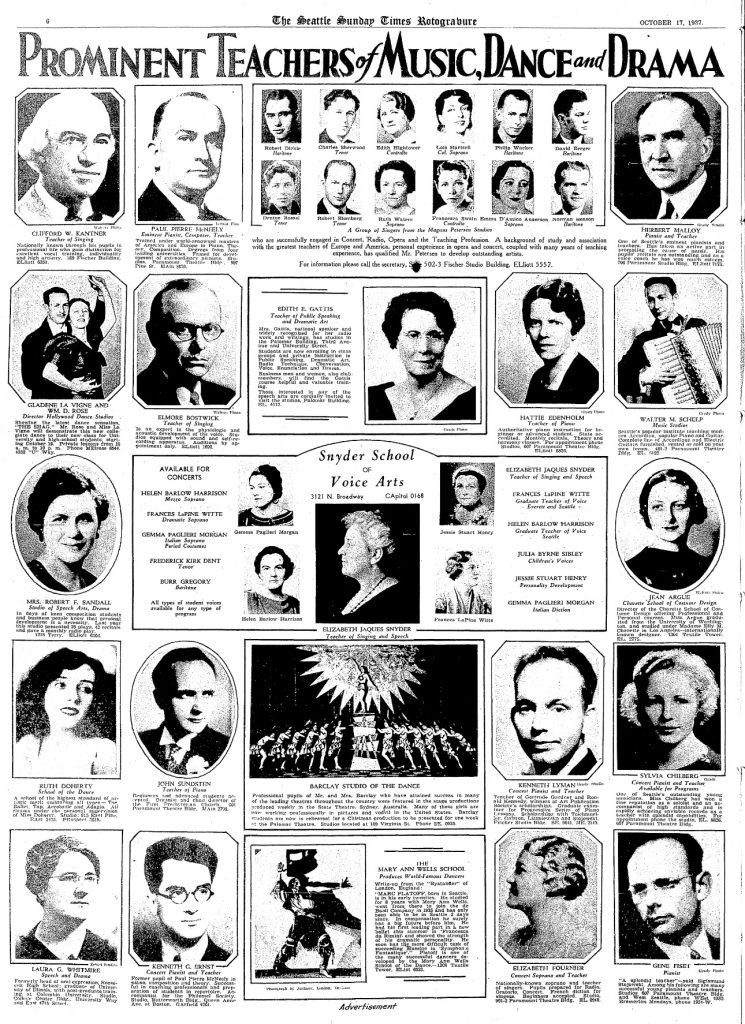

Through the middle of the century, the Paramount’s studio apartments were operating as designed, though it is unclear how many teachers actually resided in the building. Into the 1950s, the Paramount Building appeared in music and acting teachers’ advertisements. From piano to voice to accordion from Walter M. Schlep, the classifieds had a variety of lessons advertised at either 907 or 911 Pine Street or “Ninth and Pine.” A full page circular in the October 17, 1937 Seattle Sunday Times featured “Prominent Teachers of Music Dance and Drama.” Eight were located in the Paramount Building.

Unfortunately, these ads tapered off through the 1950s, until the last mention of the residences in the newspaper was an April 11, 1980 apartment estate sale. Officially, the building stopped being used for apartments in 1998. “I’ll take a lot of the blame for that,” Allen laughs. The historic features became too tempting for some residents and began to disappear. There was not an appetite in the organization to continue replacing them. By that time, the building had also started to show its age in other ways.

Separated But Together

The structure of the apartments, and some of its issues, may be most visible when walking toward the theater from loud, congested I-5 intersection to the north. From Pine or Ninth, the building appears to be a solid brick edifice. However, working down the hill on Pine, one can see there are two structures. At the bottom, there are two floors of commercial space that connect directly to the auditorium part of the Paramount, but mostly lack windows on that side. Above is seven stories of narrow, even pairs of windows. These are the former apartments, and they’re separated from the venue building by a 10-foot air gap.

The gap is a light shaft that comes directly out of tenement building 101. It allowed space for mechanical equipment such as a smoke stack for the boiler and windows that made several units into usable space. The current fire code frowns on such shenanigans. Windows to the light shaft from the interior stairway have been sealed and the fire rating on the stairway doors has been doubled with sheetrock.

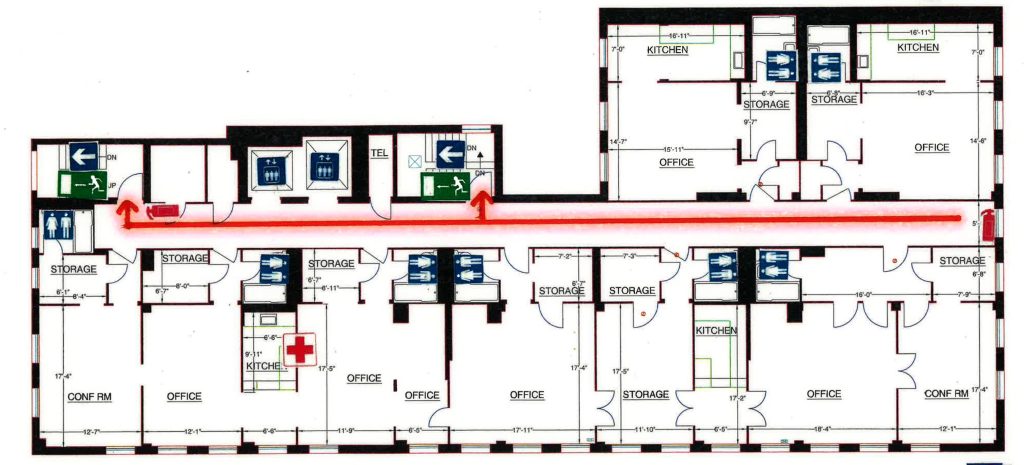

To illustrate the layout of the building, STG let me borrow their fire escape plan. To the north end, the hallway is single loaded with four studio apartments featuring windows onto Pine. The opposite side of the hallway is the interior stairway, the elevators, and a second stair open to the air on the north face of the building. The south end of the building is four larger apartments. These start on the fifth floor, above the theater’s lobby. All are now offices and conference rooms, mostly for Seattle Theatre Group.

STG is most recognized for bringing shows and performers to Seattle. (I tried to schedule this tour/interview to coincide with a performance of Six, but alas.) Their actual charter with Washington State starts with “operations of a historic theater.” That can be a heavy lift for a nonprofit. As David Allen puts it, “It depends how you look at it. Part of the fun is if you like what you do. Preserving these buildings is what we do and what we enjoy doing.” They enjoy doing it so much that they also steward the historic Moore and Neptune theaters.

Restoring the building as a residence would require significant expensive changes, beyond the wiring and plumbing necessary to come up to modern likes. The buildings survived the 2001 Nisqually Earthquake with only cosmetic damage in part because the gap between the apartments and theater allowed them to resonate separately. Returning the buildings to residences would require thickening the common wall, extending the floor plates through the air gap, and other pricy changes.

For this reason, Allen does not see the exit of resident musicians and actors as a precise loss, more of an evolution. A different type of artistry is now at work in the buildings, one that has the capacity to maintain and manage Seattle’s history. “We are preserving a skill set. A technical staff of young people loving and taking care of the older buildings.”

Together And Apart

Such older buildings are few and far between in this corner of downtown. Changes to the movie industry impacted the Paramount in the 1960’s, as theaters went from grand to suburban. The neighborhood changed too. Interstate 5 barreled through the city in the late 1960’s, ripping a scar that displaced 40,000 people. Into the 1980’s, when Allen began working with STG, a third great upheaval was underway to reshape the neighborhood.

“This was an older residential neighborhood,” Allen recalls. Then the original Seattle Convention Center on Pike Street began construction in 1985.

A 2007 oral history of the rise and fall of the Pike/Pine corridor from The Stranger (then an equally historic print edition) speaks to this latest change. Singer Anne Bonny and owner Spencer Moody fingered that construction as the point of many downtown ills. “I think the start of all this and the very worst was when they put in that whole Convention Center area, because a huge part of the city disappeared all at once… I guess people want to live in the city, but they don’t want the city.”

Since the original Convention Center opened on the east side of Pike Street, it has expanded twice. First was the 1999 development to the west side of Pike, including hotel and skybridge. Second was the recently opened Summit expansion on the west side of Pine. Now the Paramount is surrounded by the convention center on three sides.

Such development makes it look like The Paramount has always stood alone. That was not totally the case. While towards the edge of downtown, there were a number of theaters for movies and plays nearby. The Coliseum Theater on 5th and Pike became the Banana Republic store. A United Artists theater was displaced for the convention center. And the 7th Avenue Theater was just down the block on 7th and Olive.

It was the demolition of that 7th Avenue Theater in 1990 that stoked calls and interest to preserve the Paramount. While the venue had been surviving on rock shows and concerts, it was in need of a significant update and preservation. The Paramount’s precarious position in light of the loss of other theaters caught the eye of Ida Cole, who led the effort to preserve the building.

As with all preservation, the Paramount’s present comes with the question of what has actually been preserved. This opulent old theater attracts tremendous shows, but it does so alone with few of the neighbors that grew up around it. Even Seattle residents going to shows find the venue among convention hotels and tourists. If the Paramount is Seattle’s, it starts to feel like a favorite chair in the guest bedroom.

Allen takes the most recent changes in stride. He laments the loss of the views to Lake Union, those mentioned in the classifieds for the apartments so long ago. But in general, the change “doesn’t bother me, you get used to it. They brought a lot, a lot of good neighbors.”

Whatever the future holds for the Paramount, it is unlikely to be outshone by its neighbors. Unlike the theater’s marquee obscuring the one-time apartments attached to its front. These old apartments are a historic footnote to a building, and a neighborhood, that remains in the spotlight.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.