Seattle’s Planning Commission is pressing for the citywide transportation plan currently being developed by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) to contain more details around how the City of Seattle will achieve the ambitious vision laid out in the plan. Their recommendations come in the form of a letter, that the city’s official advisory body on issues around long-range planning, approved last week after a robust review of the 720-page plan and its lengthy separate environmental analysis.

The commission notes the fact that the Seattle Transportation Plan, in addition to forming a foundation for ongoing initiatives like a future Vision Zero action plan, and new areas for SDOT like a people-oriented spaces plan, will also play a significant role in determining what the next version of the Move Seattle Levy, which is the city’s most significant source of transportation funding. The current levy expires at the end of 2024, and the Harrell administration has already started work behind-the-scenes to craft its replacement. The pressure to get this right is significant.

The draft transportation plan, which is open for public comment though Monday October 23, was developed over the past few years as SDOT tried to get a handle on what it would look like for the City’s four existing plans for different modes of transportation — pedestrian, bicycle, transit, and freight plans — to be merged into one. All of those plans are fairly out-of-date, and had (for the most part) been developed independently of each other.

The Seattle Transportation Plan will also form the basis for the transportation element of Seattle’s major update to its comprehensive plan, also due at the end of 2024. The environmental analysis for that broader plan, which lays out five different strategies to guide Seattle’s development and growth over the next two decades, was due to be released earlier this year, but it has been repeatedly delayed.

The commission as a whole lauds most of the broad goals outlined in the plan, including prioritizing safety, improving the way the department prioritizes projects in a more equitable way, and increasing attention to the way the transportation system approaches climate change. But their comments spend a significant amount of time calling out a major gap in the plan between those goals and how the city intends to get there.

“I think we would like to see more flesh on the bone, we would like to see a lot more concrete actions called for that flesh out the sort of general statements of intent,” David Goldberg, one of the commission’s co-chairs, told The Urbanist. “More detail on the strategy around Vision Zero, more detail on the strategy around the arterial [streets] that are home to all of our housing, and most of our injuries and deaths.”

The planning commission has been incredibly vocal about the need for the city to think differently about transportation as it plans for significant growth over the coming decades. Last year, they issued a brief laying out a bold vision for how the city could re-envision its largest single allocation of public space across the city: street right-of-ways.

“For nearly 100 years, planning and design in Seattle have proceeded from the assumption that the primary function of the City’s public right-of-ways is the movement and storage of privately-owned vehicles,” that brief noted. “But over the 20-year horizon of the next Comprehensive Plan, several exigencies will require that default assumption to be set aside.”

A lack of an “integrated strategy”

Despite the goal of ensuring that the city’s existing plans actually become compatible with each other in service of city goals, the planning commission criticized the draft plan as falling short, pressing for a “clarity of priority” around the issue of actually making tough decisions around potential use of street space.

“Upon reviewing the draft, we are disappointed that the Plan does not articulate and demonstrate how the plans are integrated,” the letter notes. “While this Plan was intended to create an integrated vision, the draft STP appears to be a compilation of modal plans into one document, rather than an integrated strategy with clarity of prioritization criteria for decision-making where modal plans still overlap.”

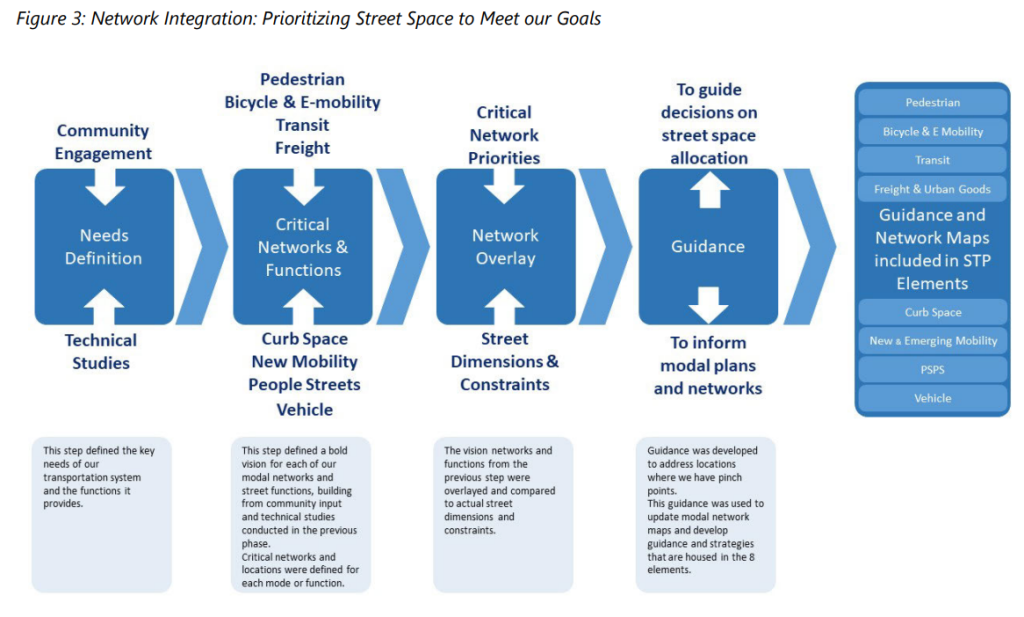

The plan includes a complicated diagram that points toward how that potential prioritization could work in theory, but away from the world of lofty plans, political decisions tend to override systems like this.

“These are really awesome goals and objectives, but brass tacks implementation, I’ve seen time and time again: business community, people, worried about losing parking … when you’ve got a bunch of different goals that are in conflict with one another, SDOT doesn’t have a strong track record of really trying to prioritize the unpopular outcomes … in the work of what folks in the community are asking for,” McCaela Daffern, the commission’s other co-chair, said in late September during a work session on the letter.

The commission takes SDOT to task for the fact that many of the specific performance metrics in the draft plan remain completely blank. A goal around decreasing the number of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) in the city, closely tied to progress around climate goals, isn’t yet filled in within the STP. Same goes for the percent of people walking, cycling, or riding transit. The plan refers to shared goals and objectives that the city has around these areas, but the planning commission wants more detail.

“What are those shared long-term goals and objectives? What is the baseline that those goals will be measured against?” they ask in their letter. Without those, the plan will remain lofty and largely detached from everyday decision-making.

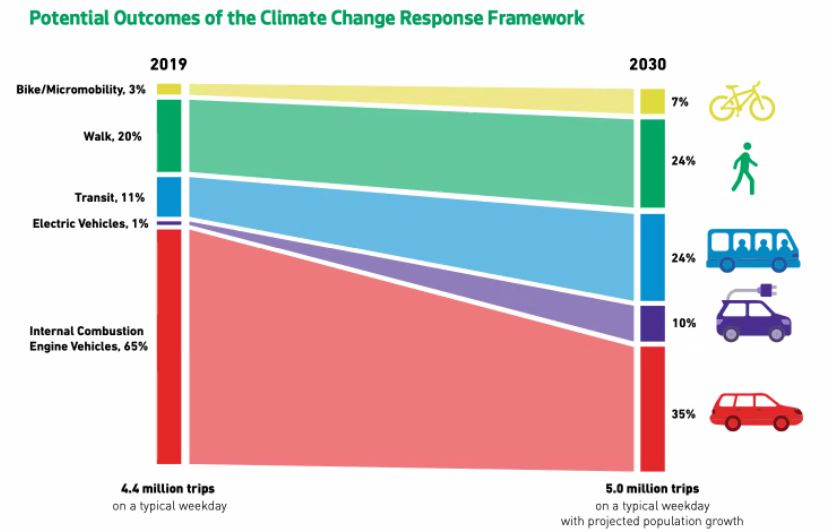

Oddly, SDOT floated mode share targets in a subsequently released “Climate Change Response Framework” but not in the draft Seattle Transportation Plan itself. Those targets would be a major lift, with transit jumping from 11% of trips to 24% of trips by 2030 and walking, rolling, and biking collectively jumping from 23% to 31% if Seattle meets its 2030 target. Internal combustion engine vehicles would shrink from 65% of trips to 35%.

The agency offered some hint at how it might hope to reach such a significant mode shift in another subsequently released document: the draft environmental impact statement for the Seattle Transportation Plan. SDOT laid out three alternatives including a no-change alternative. Over the course of the 20-year plan, the “Rapid Progress” Alternative 3, “the pedestrian network increases by 848 linear miles of sidewalks, the bicycle network adds 385 miles with facilities, an additional 76 miles of streets receive additional [people streets] improvements, and an additional 123 miles are dedicated as transit corridors,” SDOT said of its study scenario.

All that mileage would certainly make a difference, but is SDOT serious about implementation if those goals weren’t even integrated into the draft plan?

Scrutiny of how the plan addresses high-traffic arterial streets

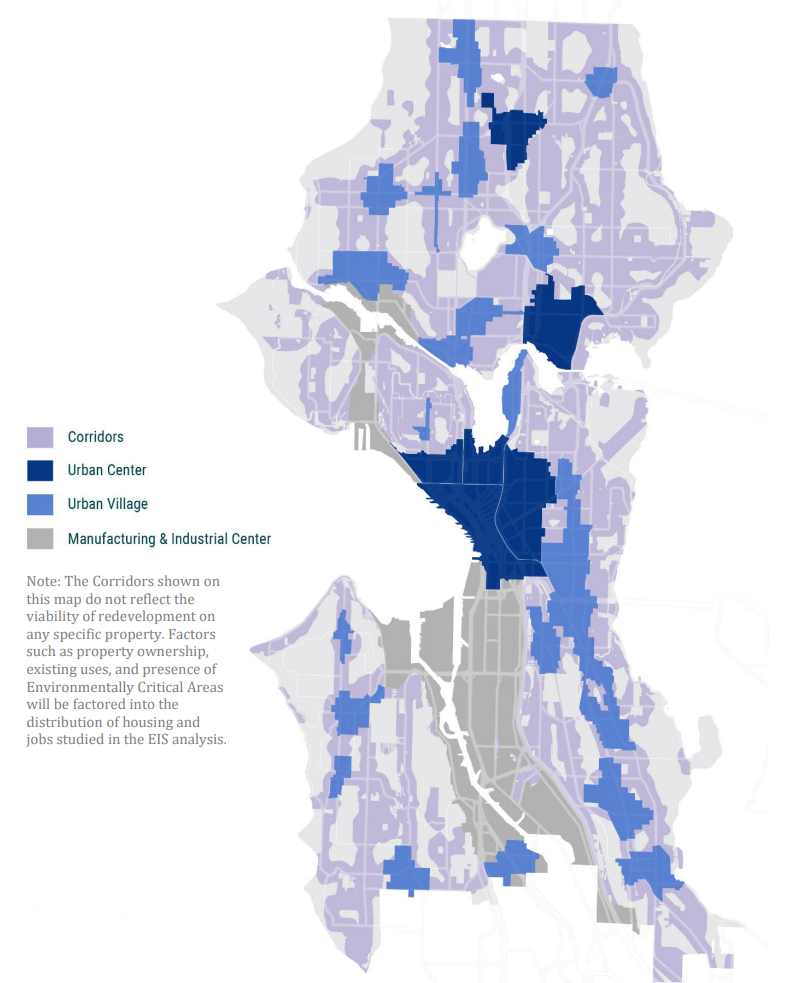

The Seattle Planning Commission, given their mandate to guide the city’s growth strategy, is particularly interested in the issue of how the Seattle Transportation Plan interacts with the Comprehensive Plan update. The commission has been vocal in the need for the city to move away from a strategy that concentrates new housing in a minority of the city’s land area and encourages new residents to live along high traffic arterial streets.

Many of the scenarios being looked at as part of the comprehensive plan’s environmental analysis continue this trend, including the “corridors” alternative, which envisions significant growth in the number of areas where multifamily housing would be allowed, but maintains that growth around those busy corridors where the City has been slow to modify the amount of street space available for other uses. City planners have given some indication that multifamily zoning would extend a few blocks out from the arterial streets, but seeing that proven out in the draft plan would provide more assurance.

“The City has encouraged the placement of multifamily housing along major arterials like SR-99 and Rainier Avenue South for decades and appears poised to further invest in this strategy with the upcoming growth strategy,” they note. “The City will likely continue co-locating car traffic and freight with transit in ways that push out other modes. We encourage SDOT and [the Office of Planning and Community Development] to show how the Corridors concept uses other modes to support economic growth and future housing locations.”

“The comp plan policy should be driving a lot of what this plan does,” Goldberg said of the Seattle Transportation Plan. “I remain really concerned that the parts that talk about land use, they’re referring to a growth strategy that we’ve criticized and that we plan to move on from … and so I think that’s a problem.”

The commission asks for a fully detailed, comprehensive strategy for how SDOT plans to address the integration of multiple modes on busy arterial streets. In 2021, in the lead-up to direct outreach on the STP, an internal work group at SDOT looked at how much conflict really existed between the current modal plans, and found that on-street parking, more than conflicts like transit versus bike lanes, was set to be the biggest barrier to integration.

“When we say that one of our biggest issues with this plan is, when it was set out to be an integration of the modal plans, and when it’s all said and done it looks like the modal plans have just been stapled together, and you can’t really — easily, anyway, without flipping back and forth, a lot — get a handle on what it is we’ve done to integrate in the places that really triggered this, which is… the arterials,” Goldberg said.

Ensuring that the Seattle Transportation Plan, and ultimately the Comprehensive Plan that it informs and shapes, actually contain a viable pathway to the laudable goals and outcomes put down on paper will be pivotal to ensuring that the amount of time invested in the plan was not in vain.

You can comment on the draft Seattle Transportation Plan through October 23.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.