Public Works continues to delay long-promised safety upgrades even as a repaving project presents an opportunity to redesign the dangerous street.

Bremerton has planned to convert 6th Street from a dangerous four-lane street into a three-lane street with a bike lane, commonly known as a ‘road diet.’ The road diet was explicitly and repeatedly recommended in numerous official City of Bremerton studies or reports dating back to 2007. In 2024, 6th Street will undergo the third and final phase of the $3.7 million resurfacing project — constituting a low-cost chance to make the improvement. So why is the Wheeler administration planning to complete a 6th Street repaving project next year without including the road diet and bike lane?

6th Street: The Lowest Hanging Fruit

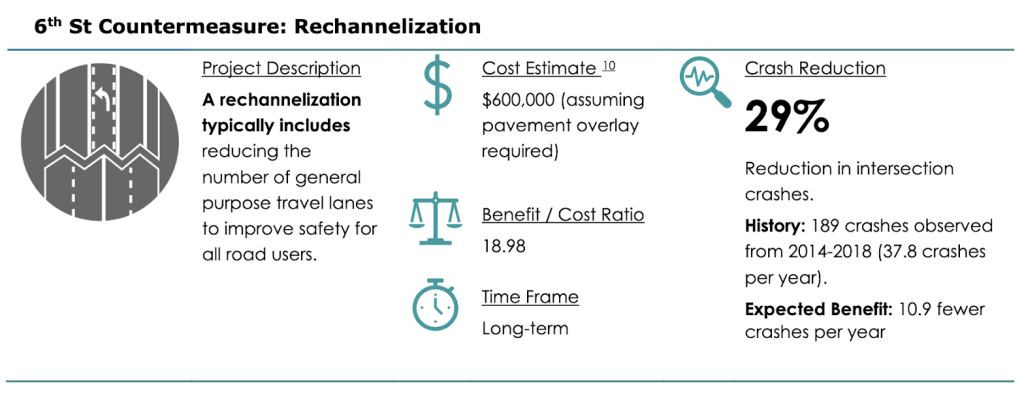

A bike lane on 6th Street has been studied extensively, and every single study – 10 in a row — have explicitly recommended a road diet on 6th. It’s not hard to see why. A 2020 study noted that 6th Street has “crash rates which are approximately 2.5 times the Kitsap County average.” (p. 38). A 2020 study predicted the road diet would result in a “29% reduction in intersection crashes.”

6th Street’s short 1.4-mile length runs near five schools, a park, Bremerton’s largest homeless shelter, and dozens of homes and businesses. The 6th Street road diet has ample support, including from both Downtown and Charleston Business Associations, which are connected by 6th Street, and virtually nobody outside of the Mayor’s office opposes the road diet, at least not publicly.

And yet, the City plans to complete the $3.6 million repaving project and not paint the bike lanes. Baffled? Let’s learn more.

The Most Studied Bike Lane in Bremerton

As mentioned, the 6th Street road diet has been supported by no fewer than 10 official City of Bremerton documents since 2007. Bremerton City Council voted in favor of documents supporting a 6th Street road diet by a combined tally of 31-4 and signed by three different Bremerton mayors.

Here’s a list:

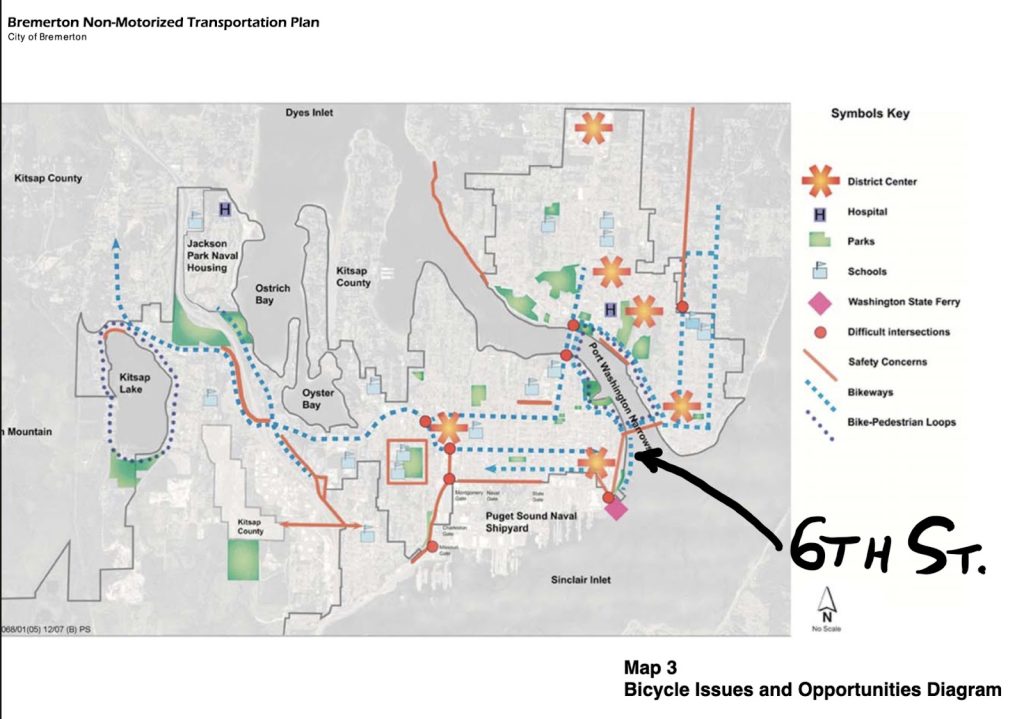

- 6th Street was first formalized in the 2007 Non-Motorized Transportation Plan (NMTP), an addition to the 2004 Comprehensive Plan. “In Bremerton, several streets appear to have more width than is currently needed for vehicles and this excess capacity could be stripped for non-motorized uses. 6th Street in West Bremerton currently provides four vehicle travel lanes, yet traffic volumes are relatively low compared with nearby parallel routes such as 11th Street and SR 304/Burwell Street.”

- 2007 Downtown Sub Area Plan, which passed unanimously, designated 6th Street as a ‘Multimodal Street’ and argued, “Sharrows or dedicated bike lanes should be added to all multimodal streets.” (p. 5-72).

- 2012 Complete Streets Ordinance (BMC 11.10) stated, “Public Works and Utilities Department will plan for, design, and construct all new transportation improvement projects to provide appropriate accommodation for pedestrians, bicyclists, transit riders, and persons of all abilities…”

- 2016 Comprehensive Plan – 6th Street designated as a ‘Minor Arterial.’ “These corridors could be the focus of targeted bicycle and pedestrian improvements.” It stated, “Bremerton’s walking and bicycling results indicate that many streets near Downtown Bremerton are especially attractive for walking and biking uses. Vital streets that serve as a link to a variety of uses and destinations scored highly, including…6th Street.”

- Bremerton’s Complete Street Ordinance (BMC 10.11) – passed in 2012, updated in 2017, combined votes 12-2, signed by Mayors Lent & Wheeler. “The complete streets program shall apply to all phases of City transportation capital projects [including]…new transportation projects, reconstruction projects, and retrofit projects…” More on this later.

- 2018 Bremerton Complete Streets Map – 6th Street is labeled an official ‘Complete Street,’ thus requiring 6th Street bike facility to be ‘Completed’ during any City reconstruction or repaving project, (BMC 11.10). Thus, not building the 6th Street road diet during the current repaving violates BMC 11.10.

- 2020 Bremerton Strategic Road Safety Plan – “6th Street Countermeasure: Rechannelization … 29% reduction in intersection crashes.”

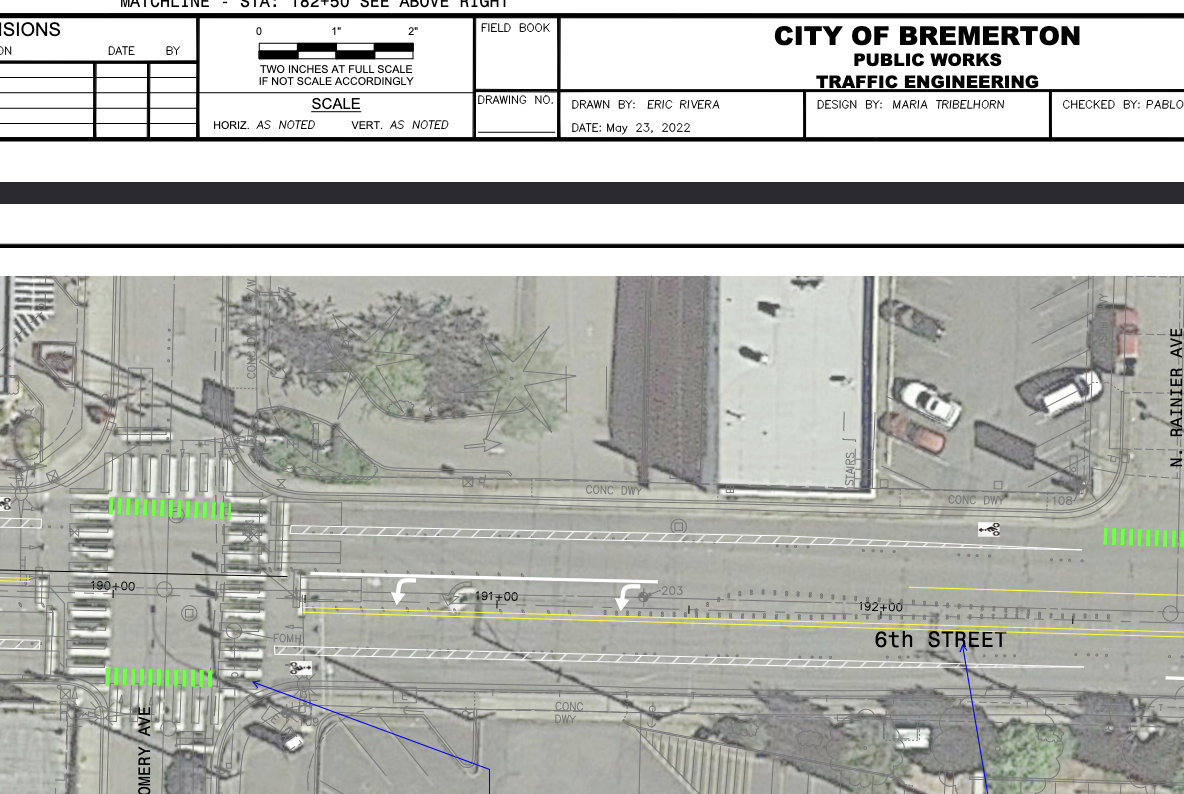

- 2020 6th Street Road Diet Traffic Engineering Maps – Created for the City of Bremerton by PH Consulting, completed as part of a grant application.

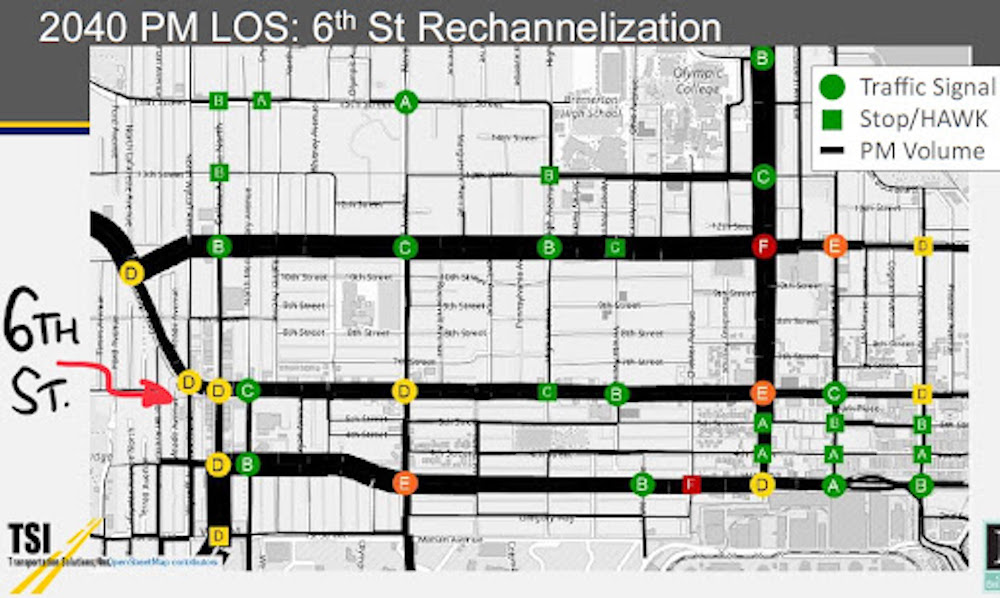

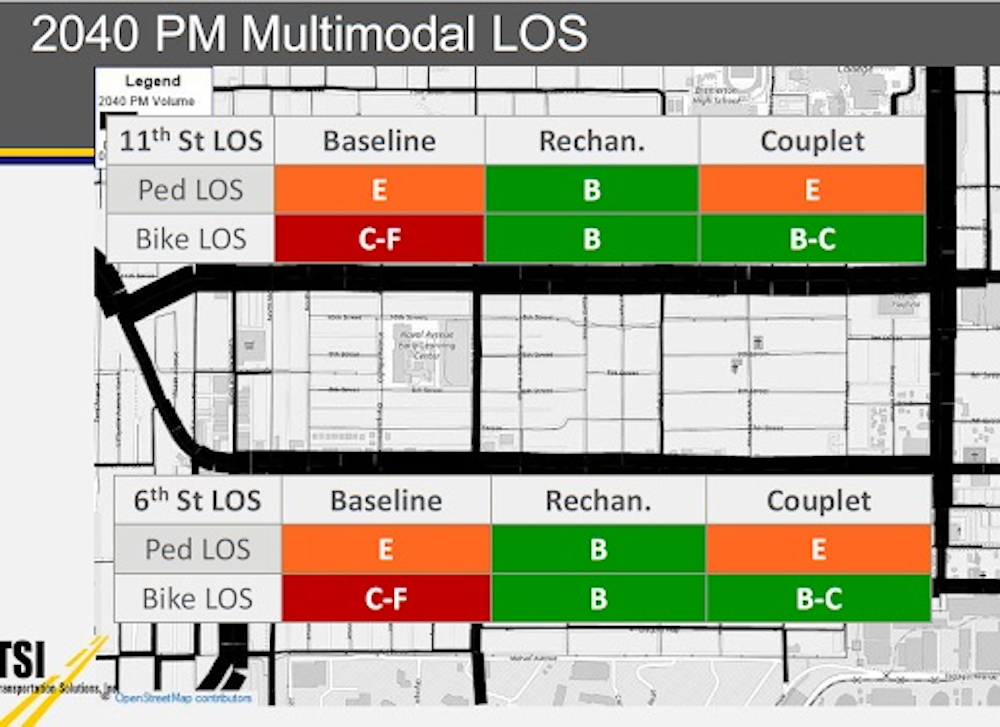

- 2020 6th/11th Corridor Feasibility Study – This $100,000, 250-page ‘6th/11th 2020 Corridor Study’ analyzed pre-pandemic traffic flows at every major intersection in Central Bremerton’s 6th Street. The study concluded: “A road diet is typically the preferred tactic for minor and collector arterials, while access management is typically the preferred tactic for principal arterials. Following this logic, 6th Street is a logical candidate for a road diet.” (p. 42) As shown below, the study found Projected Car Level of Service comparing ‘Baseline’ (stays four lanes for cars) and ‘Rechannelization’ (4-to-3 road diet). ‘A’ is no backups, ‘F’ is bad traffic. The 6th Street road diet has hardly any effect at all on cars. Bikes and Pedestrian Level of Service improves dramatically with the rechannelization.

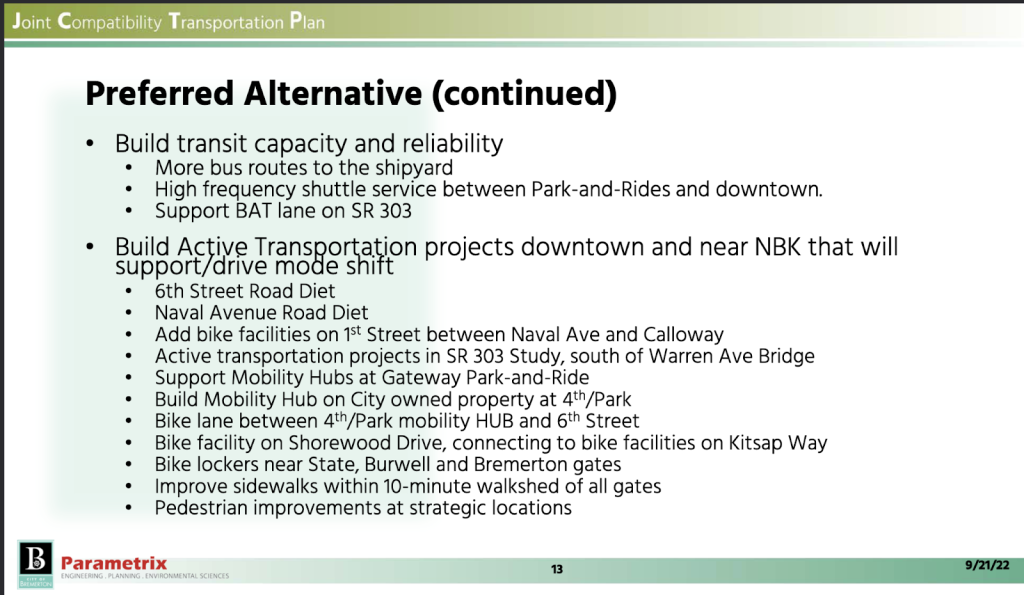

- 2023 Joint Compatibility Transportation Plan – “Build Active Transportation projects downtown and near NBK that will support/drive mode shift.” First project recommendation: 6th Street Road Diet. JCTP Chair: Mayor Wheeler.

The Wheeler Administration Violates the Complete Streets Ordinance for 6th Street

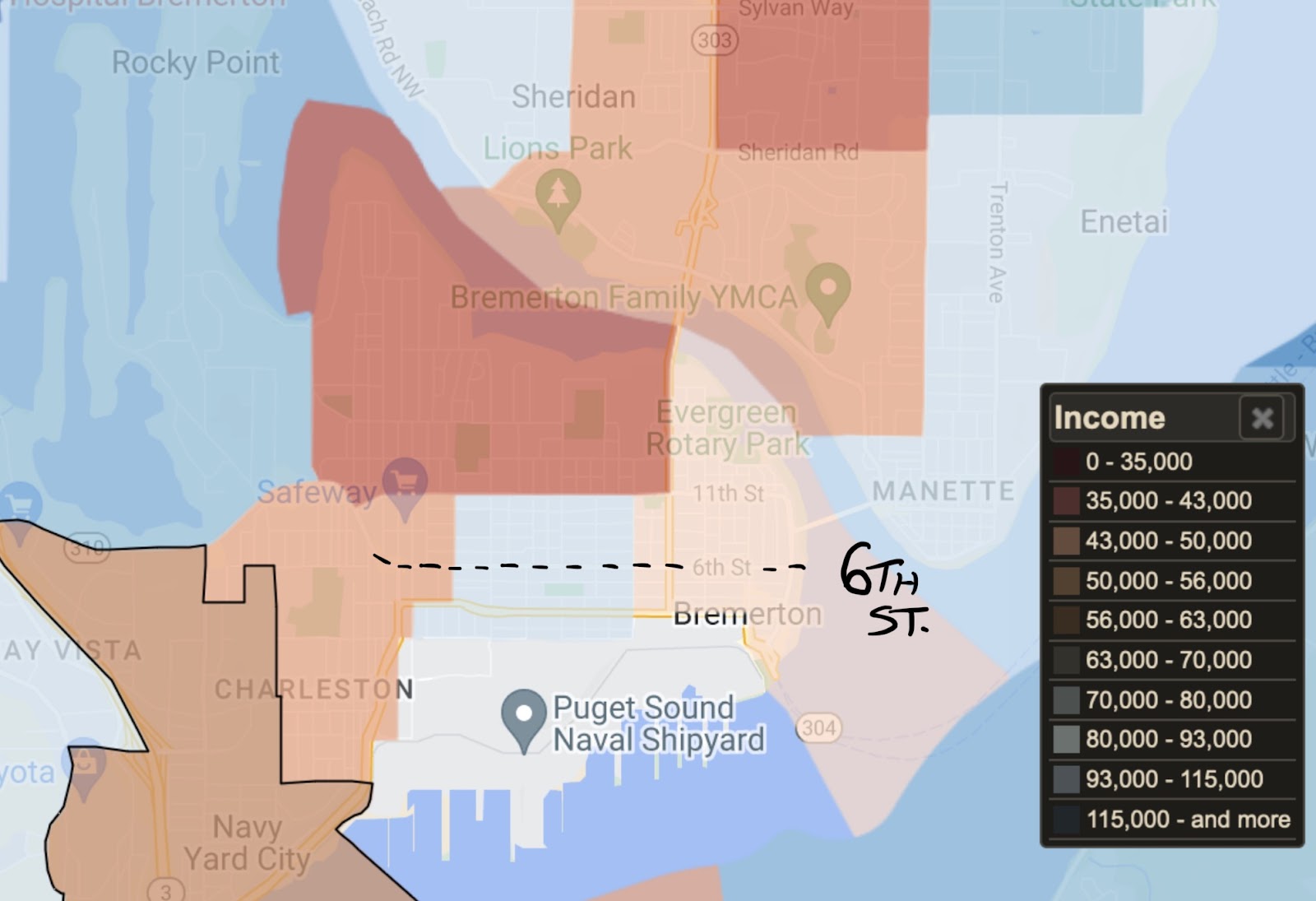

For 17 years, Bremerton City Council has been crystal clear about the ideal future state of 6th Street. By passing the Complete Streets ordinance (BMC 11.10), Council sought to require improved bike infrastructure on certain streets, especially, “High need area/community of need,” defined as “(1) Any census tract in which the median household income is less than 80% of the statewide median (2) An area that has a high number of pedestrian and/or bicycle collisions.” (BMC 11.10.020.c.1-2).

There’s no question that 6th Street fits the ordinance’s definitions. The three census blocks that 6th Street passes through have a median income of 67% of State average and the City’s 2020 Corridor Study noted “[c]rash rates for 6th Street… are approximately 2.5 times the countywide average” (p. 8). Furthermore, 6th Street is clearly delineated on the City’s Complete Streets Map.

Thus, the Wheeler administration has no plausible claim that 6th Street is exempt from the requirement that, “The complete streets program shall apply to all phases of City transportation capital projects… from the start of planning and design work through construction.” And yet, when Phase I ($1.1 million total, $444,000 City match) and Phase II ($1.6 million) of the 6th Street repaving project went to bid in 2020 and 2022, neither included multimodal improvements.

However, the Phase III grant application seemed set to include bike lanes. The application included detailed engineering drawings of where bike lanes would be painted, and included this phrase (p. 3) “An increase in bicycle trips is anticipated due to the increase in safety and comfort achieved by the road diet and buffered bicycle lanes. Road diets calm traffic, and reduce vehicle speeds. Buffered bicycle lanes increase horizontal separation between bicyclists [sic] and cars. All users [sic] groups who desire to walk or bike in the corridor will benefit.” But it was just a bait-and-switch, and the administration now claims unprotected bike lanes are too complicated for Phase III. More on that later.

The ‘Exemptions’ clause in the Bremerton Complete Streets Ordinance notes that the 6th Street repaving project is not an obvious candidate for any of those exemptions, and an exemption was never sought by Public Works. According to BMC 11.10, the administration had the option to exempt itself from complete streets requirements, but they ignored that process. To activate an exemption, “[t]he Director of Public Works will notify the Public Works Committee of project exceptions to the complete streets program set forth in subsection (b) of this section prior to exception being granted…” Public Works Director Thomas Knuckey has never presented an exemption to the Public Works committee for any of the first two Phases of the 6th Street Repaving, in violation of BMC 11.10.

The complete streets ordinance has no enforcement mechanism, such as fines or an appeals process, despite decisions like these failing to implement it endangering the hundreds of kids who go to school near 6th Street. Such a toothless ordinances can be ignored. In the absence of a means to legally enforce this code, a political solution is required.

The $3 Million Per Mile Bike Lane

Clearly unsupportive of a near-term, inexpensive bike lane on 6th, the Wheeler administration instead showed what a champagne budget might buy. In 2022, the administration applied for (but did not win) a $737,000 Federal grant administered via the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC), The grant only covered engineering ($700,000) and right-of-way purchases ($150,000) to blow out intersections. The eventual $4.1 million price tag would have included $3 million plus for construction and would have required a nearly $600,000 match from city funds. Construction wouldn’t have begun until 2028. A 1.4-mile bike lane that costs $4.1 million might have been the most expensive paint-only bike lane in American history.

The Wheeler administration’s preference for grand, expensive streets projects forces two great costs upon Bremerton. The first cost is that large grants require large matches from City funds, which compete with sidewalks and homeless services. Secondly, the large grants reduce focus on practical solutions, like connecting existing bike lanes into a comprehensive network. For instance, a two-block gap separates Bremerton’s new 11th Street (Manette neighborhood) bike lane from the Manette Bridge bike lane.

“It’s Too Hard” – The City’s Resistance to a Safe 6th Street

The Wheeler administration claims they want a bike lane on 6th Street, just not now and not inexpensively. The administration provides two rationales against building the 6th Street road diet in 2024. First, they say, it’s impossibly difficult to ‘rechannelize’ the street on such short notice. Secondly, they will win a large grant to complete the work at some point in the distant future.

The ‘it’s too hard’ argument was elucidated in an email Public Works Director Knuckey sent to City Council on Oct 18, 2023. Several points are easily rebutted.

- It’s too hard #1: “There is a common misconception regarding [that] believing the project would be low-cost and limited… to re-channelize 6th Street,” Stuckey wrote. – Yes we do think that, because that’s what Public Works repeatedly told citizens and Council. In multiple statements from 2020 to 2022, Public Works officials repeatedly stated that the road diet could be easily achieved in Phase III (presumably to avoid having to complete it section by section in Phases I and II.) One example from a July 2020 Public Works committee meeting when Councilmember Lori Wheat said: “Did you say that the third phase of the 6th street preservation project from Warren Avenue to Naval… could be done concurrent with the third phase of the project, the Naval to Warren portion?” Shane Weber, Public Works engineer replied, “When you convert from a four to three lane facility you are not moving the curb, you are just changing the channelization in-between, so it’s a pretty easy forward compatibility project for us to implement.”

- It’s too hard #2: “We currently estimate the cost to design and construct the re-channelization at $2.5 million” Lots of cities do road diets during repaving, when machinery is already in place and they are painting lines anyway. From a 2013 study of the costs of building bike infrastructure projects in Portland, Oregon. “The City of Beaverton, Oregon, installed bike lanes on a one-mile stretch (two miles of bike lanes total) of a residential, collector road … The project cost $5,000 for design and engineering, $2,400 for labor, $6,000 for materials, and $250 for equipment, for a total of $13,750, or $1.30 per foot.” A separate, 2018 Federal Highway Administration study estimated the cost of a road diet to be $100,000 per mile.

- Phase III funds can’t build bike lanes: “A further note that the grant funding that is being used for this work is for “pavement preservation” only, which generally includes the overlay and related work.” That’s simply untrue. The official Phase III Notice to Consultants also included language placing the bike lane firmly inside the anticipated ‘Scope of Work.’ “…The City may elect to have the re-channelization completed as part of the project or have the project designed to be forward compatible with a future project to re-channelize to this lane configuration. The CONSULTANT shall consider this in their approach to the project.“

- “[N]one of the evaluations or design has been completed yet”: In fact, a tremendous amount of work has been done to plan for the 6th Street road diet since 2007. One recent example is the: 2020 6th Street Road Diet Traffic Engineering Maps that were created for the City of Bremerton by PH Consulting, completed as part of a grant application. Another is the 2020 6th/11th Corridor Feasibility Study – This $100,000, 250-page ‘6th/11th 2020 Corridor Study’ analyzed pre-pandemic traffic flows at every major intersection along Central Bremerton’s 6th Street and 11th Street. The study concluded: “A road diet is typically the preferred tactic for minor and collector arterials, while access management is typically the preferred tactic for principal arterials. Following this logic, 6th Street is a logical candidate for a road diet.”

- Too much traffic: Bremerton’s 6th Street has a 12,000 average daily traffic (ADT) count, which opponents claim is too high for a simple Road Diet. That’s simply not factual. The Federal Highway Administration compiled maximum ‘Average Daily Traffic’ ADT recommendations for road diets from local transportation departments across the country. Seattle was up to 25,000 ADT, Chicago: 15,000-18,000 ADT, and Kentucky – up to 23,000 ADT.

Opponents of a road diet on 6th Street view the project as ‘anti car.’ While 4-to-3 road diets do have some negative effects on rush hour commuters, like lengthening rush hour queues at stoplights, dozens of studies show road diets don’t significantly increase travel time.

And road diets provide a plethora of benefits to cars, including reducing crashes and improvements for cars entering the road diet street from driveways and side streets. Road diets reduce both excessive speeding and erratic driving by impatient drivers (like sudden weaving to avoid a turning car or bus stop). And road diets make congested car/bike/pedestrian interactions less stressful for drivers by making bikes and peds more predictable — bikes stay in the bike lane and kids don’t dash across four lanes of traffic. The 6th Street road diet is not part of the so-called ‘war on cars.’

The Politics of Bremerton’s 6th Street Road Diet

The single greatest obstacle to 6th Street – and the larger multimodal network – is Bremerton Public Works Director Tom Knuckey. Knuckey has a long history (26 years in Bremerton Public Works) of opposing bike projects in general and 6th Street in particular. Presumably, he believes a 6th Street road diet will have negative impacts on car traffic, which is a defensible position. But Knuckey doesn’t make the traffic case, instead he argues that it’s simply impossible to build a paint-only road diet in 2024, given various and sundry technical and funding complications.

The Public Works director’s boss, Mayor Wheeler, has full authority to change his mind and support the 6th Street road diet, and he just might. Mayor Wheeler showed keen understanding of the importance of a multimodal (buses, bikes and cars) transportation network with the results of the 2023 Joint Compatibility Transportation Study (JCTP) a Department of Defense-funded, long-term transportation study he chaired. JCTP recommended an enlightened set of recommendations to accommodate sailors and citizens for Bremerton’s rapid growth, including a 6th Street road diet. But the Mayor has been unable or unwilling to direct his staff to accomplish the long term goals which he championed in the JCTP. Maybe that will change.

The other political force in Bremerton is the city council. At least four councilmembers have expressed to advocates that they favor the 6th Street road diet, as a majority of council always has. Council is considering a resolution to reinforce the complete streets ordinance, with a focus on 6th Street. But the City council can’t force the mayor to obey the law. The council’s strongest power is the ‘power of the purse,’ which they could use to attach a rider to the $350,000 City match, requiring the bike lane and providing extra city funds to support engineering studies. Maybe they will.

By 2040, Bremerton’s population is projected to increase by 50%, and employment at the Central Bremerton Naval Shipyard will increase by 25%. Bremerton simply cannot increase its car carrying capacity to meet that growth. It must focus on transit and multimodal travel and create safe transportation options for residents and commuters to coexist in a crowded city. 6th Street is the lowest hanging multimodal fruit in a city that desperately needs future-oriented transportation solutions.

Join others to support safe and active streets in Bremerton at the Rally for 6th Street Road Diet, Wednesday, November 1, 5:30pm. Meet at the Norm Dicks Government Building, Kitsap County Health.