Homebuilders won a brief reprieve with council opting to delay its impact fee push — for now.

The Seattle City Council declined to approve a bill Tuesday that would have been the next step in approving a citywide transportation impact fee program, along a narrow 4-to-5 vote. The fees, which are levied on new residential and commercial development, are authorized under state law and can only be used to fund capacity expansion projects for any transportation mode.

Seattle has long been an outlier in Washington in not having a transportation impact fee program, with over 70 other jurisdictions having fees of certain sizes in place, in addition to impact fees for other infrastructure like schools and parks. But facing a housing affordability crisis and a need for more homes, housing advocates argued that outlier status is justified.

Proponents of the fees argue that increased demands on transportation infrastructure created by new residents and office workers should be directly shouldered by homebuilders and commercial developers, rather than broad-based taxes. But housing advocates and affordable housing developers have raised significant concerns about adding additional fees to new housing at a time when state projections call for Seattle to add a minimum of 112,000 new units of housing by 2044 to meet demand.

With Seattle’s position as a jobs center for the entire region, transportation impact fees on housing in core neighborhoods could have the effect of pushing development to suburbs, adding more strain to the regional transportation system and producing the exact opposite intended effect of the Growth Management Act.

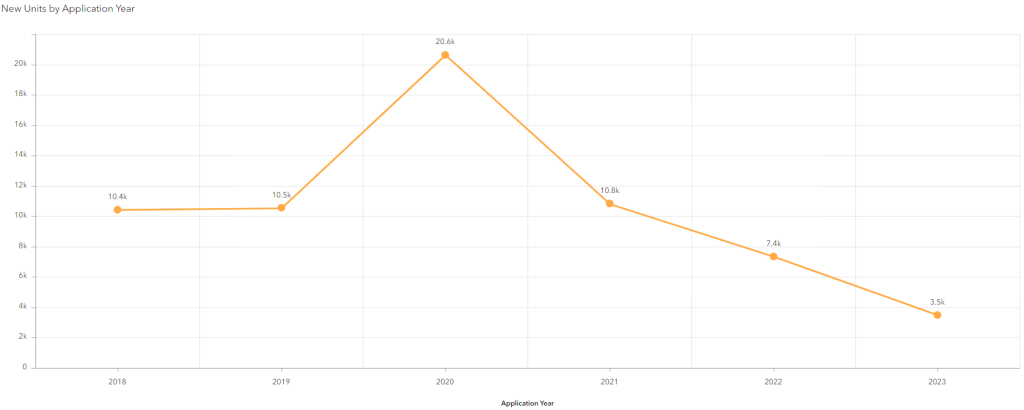

The city is already seeing a sharp decline in the number of new housing permit applications, even as a significant number are finally coming online after entering the development pipeline years ago. Builders have cited high interest rates, jumps in labor and material costs, Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability fee added in 2019, and stringent building code updates as contributing factors to the slowdown, which has no one single cause.

Tuesday’s vote was a significant defeat for outgoing councilmembers Alex Pedersen and Lisa Herbold, who were trying to tee up the issue ahead of a new city council taking office before their terms expire at the end of this year. Imposing impact fees has been a long time goal for both councilmembers, with Pedersen’s office commissioning an independent poll earlier this year that showed 75% approval for some type of transportation impact fee. The council can’t vote again on updates to the city’s comprehensive plan until next year.

“Yesterday was a great day for housing policy as the council voted to fail the transportation impact fee proposal,” Patience Malaba, executive director of the Housing Development Consortium, told The Urbanist. “Seattle needs more homes to address our deepening affordability crisis. In the face of challenges posed by high interest rates and construction costs, homebuilders are already contending with the difficulty of making new housing projects financially viable. The timing and place of the proposal couldn’t have been worse. We are thrilled to build on this decision and anticipate a promising 2024, working with the new council in collaboration with the Mayor on proactive solutions to address the pressing issues in our community.”

Malaba joined Futurewise’s Alex Brennan in laying out why moving forward with a transportation impact fee right now would be a bad decision earlier this week in The Urbanist. The editorial board of The Urbanist also came out against imposing impact fees in Seattle.

Over the past few weeks, a sharp divide emerged among councilmembers who presented the vote as merely procedural and those who saw the step as advancing a significant change in city policy. An amendment proposed by Councilmember Herbold even changed the language in the bill that directed a future council to impose impact fees to instead read “shall consider use” of the fees. But that softening of the language, seen as being less binding on a future council, called into question why the bill was so urgent to pass before the end of the year at all.

The vote ultimately failed after Councilmember Tammy Morales, who voted to hold a public hearing on the proposal earlier this month, voted no. Morales has signaled support for the idea of transportation impact fees in the past, citing the need to build missing sidewalks and other infrastructure investments in her South Seattle district. But this week she said the bill was premature, and that transportation impact fees are just one potential tool that Seattle can use to raise revenue for transportation.

“I do think that this is an important conversation… I do want to see us include this,” Morales said. “And I think that that is a conversation that we need to have in the context of the larger Comprehensive Plan update that we’re doing next year.”

Morales mentioned proposed zoning changes for equitable development that she proposed earlier this year that could be part of the conversation, in the overall context of how Seattle sets the stage for growth over the next two decades. The major update to the Comprehensive Plan is due at the end of 2024, but Mayor Harrell’s administration has postponed the release of a full proposal that was originally set to happen in April.

Councilmember Dan Strauss, who had been leading this bill through his land use committee until it was pulled out so that it could be passed with the 2024 budget, also argued that the city wasn’t yet ready to take this step, and that a better course of action is to do everything at once next year.

“There is the opportunity to pass this comprehensive plan amendment as a package at that time,” Strauss said. “I think that we’re operating with different perspectives about the same facts.”

Mayor Harrell and the city council will also be queuing up a renewal measure for the Move Seattle transportation levy to go to voters in the fall of 2024. Pedersen had argued impact fees could offload costs from homeowners to homebuilders, but it appeared likely tenants would bear the brunt as costs are passed on and apartment development slows.

Councilmember Sara Nelson, often an ally of Pedersen’s, split with him and also voted no. She cited comments her office received from business and housing advocates, including the Housing Development Consortium, who raised concerns about adding new costs to housing right now. “I tend to go with the experts, is what I’m trying to say, and that is what gives me pause on this legislation,” Nelson said.

Councilmembers Andrew Lewis and Teresa Mosqueda, who have been vocally opposed to adding impact fees, joined as the rest of the coalition that blocked the bill from passing.

The size of the fee that the city could levy is set by an independent rate study that is based on a specific list of transportation improvements the city identifies. But the list that was rejected Tuesday was the same one that had been considered by a previous city council in 2018, the last time a significant attempt was made to pass the fees. Some projects had been removed, but others had been left on, including the Madison Street RapidRide project, which is already fully funded and under construction. To fully approve impact fees, a future city council will almost certainly need to update the list again, making this step questionable. With that ceiling set by the list of projects, the council can approve any impact fee that is lower, so it needs to be updated every time projects are added or removed.

A future city council could move fairly quickly to implement an impact fee program, though they would likely need to update the rate study to include a new list of projects. But the bigger question is whether a brand new city council — with six new members — will make imposing transportation impact fees a policy priority given the number of significant issues facing the city. Most of the incoming councilmembers told The Urbanist during this year’s campaign that they support impact fees in theory, some more than others.

No timeline is known, but it is pretty clear that the issue of transportation impact fees won’t be going away for long.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.