Landlords are pushing to delay implementation schedules and lessen fees.

When asked about the causes of climate change, most may picture cars, coal mines, and power plants. But fewer consider the buildings we occupy. Yet, our buildings represent a sizable portion of planet-warming emissions.

Nationwide, residential and commercial buildings account for around 13% of annual planet-warming emissions. That’s more, even, than the agricultural sector. In places like Seattle, where we have a carbon-neutral utility and limited amounts of agriculture, buildings (counting the industrial sector) account for an even more significant slice of annual emissions: 37%. The buildings sector in Seattle is second only to the transportation sector, driven by the cars that clog our ill-designed streets.

This reality, and the fact that existing buildings are unlikely to make emissions-reducing upgrades until they have to, is putting the City of Seattle in the position to push building owners to cut emissions as quickly as possible. At the end of former Mayor Jenny Durkan’s term, she issued an executive order to the Office of Sustainability and Environment (OSE) mandating that they establish standards for all large buildings in the city to meet, which would force the building sector to cut carbon. Over the last two years, OSE’s buildings team has done just that. The process, however, has been anything but simple.

For those of us uninvolved in the nuances of policy development but nonetheless heavily invested in their outcomes, it seems simple enough for the city to set strict, ambitious standards that would force large buildings throughout the city to achieve carbon neutrality as quickly as humanly possible, whatever the financial obstacles may be, because the market must adapt to planetary realities, or perish, along with the rest of us.

In reality, city staff have been faced with the challenge of balancing feedback from stakeholders that represents building owners, labor unions, climate advocates, and others. Not only have these different segments contributed conflicting comments, disagreement exists inside some stakeholder groups.

OSE began engaging with the public as soon as then-Mayor Durkan submitted the Executive Order. Over the next year, OSE staff held two open house meetings, six meetings with a multi-talented technical advisory group, six meetings with an affordable housing advisory group led by the Housing Development Consortium, and an assortment of closed-door meetings with various stakeholders. With this input, OSE staff developed an initial draft of the policy, and then between late 2022 and the first half of 2023, they engaged stakeholders further.

The initial meetings clarified the scope of the policy but also revealed the tensions that would place OSE’s buildings team in the middle of a tug-of-war between building owners, labor unions, and environmental advocates.

The first piece of clarification that emerged was that to truly accomplish the goal stated in the executive order — reducing building emissions — the policy needs to go beyond a similar, statewide policy that targeted energy use within buildings. That’s exactly what the city team did.

Jonny Kocher, Carbon-Free Buildings Manager at Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), has been supporting environmental advocacy with on-going analysis of the building emissions performance standards policy as it has been developing.

“The Washington State code will make sure that people aren’t doing inefficient electrification,” Kocher said. “But the Washington State building performance standard doesn’t talk about emissions, so it doesn’t get at the heart of the problem, which is climate.”

Since the Seattle policy explicitly targets building emissions, Kocher said “they actually complement each other really well.”

While this focus was met with immediate support from environmental groups like the Sierra Club and Climate Solutions, not everyone was ecstatic to see the city emphasizing building electrification. While MLK Labor passed a resolution in support of BEPS, other labor unions like UA Local 32 and LiUNA expressed concerns that, though the policy might create between 150 and 270 jobs every year, the focus on electrification would lead to a slow but steady loss of jobs for the gas pipefitters in their unions.

To remediate this impending loss, UA Local 32 and LiUNA urged the city to avoid prescribing the pathways that building owners should take to meet the emissions targets laid out in the policy. Moreover, they recommended that the city include in the policy reference to what they saw as decarbonization alternatives, specifically synthetics, biofuels, green hydrogen, and so-called “renewable natural gas.”

While some might think that when we replace fracked methane gas with “renewable” methane gas, that we can limit some of the associated hazards – including increased rates of childhood asthma among those raised in homes with gas-powered stoves, furnaces, and water heaters – that’s simply not the case.

Deepa Sivarajan, the local policy manager for Seattle-based Climate Solutions, pointed to this problem. “We don’t think that renewable natural gas is a good solution for building decarbonization,” Sivarajan said. “Heat pumps are a really good solution for buildings on so many levels that using renewable natural gas in buildings just isn’t economically sound. And one of the other issues is that the indoor air pollution implications are exactly the same as fossil gas. If you are using a gas stove, renewable natural gas is methane just like fossil gas is, so you’re still not reducing the air pollution aspect.”

Regardless of these concerns, OSE Director Jessyn Farrell said during a press conference on June 8th that, for the policy to be legally defensible, the city can’t prescribe pathways for building owners. So, renewable natural gas remains an option despite the only differences between renewable and fossil methane being the way it is produced and collected.

So-called “renewable” methane is captured at capped landfills, livestock facilities, wastewater treatment facilities and other locations that don’t involve direct extraction from the ground. These processes supposedly reduce atmospheric carbon emissions by preventing gases from entering the atmosphere, but the irony of offsets awarded for these practices is that the gasses are nonetheless transported via pipelines into cities to be burned, resulting in emissions from use and from pipeline leaks.

While there seem to be many reasons not to allow methane gas to be a part of our building decarbonization agenda, that’s not to say climate advocates are calling for the people working in gas-associated jobs to be abandoned. There’s no justice in that. Instead, they argue it’s essential that we support those workers in finding new jobs that are appropriate for the carbon-free economy emerging in the city. This is something the unions themselves supported.

During the stakeholder engagement, UA Local 8 and LiUNA recognized that given the protracted timelines proposed by the policy, there is more than enough time for the City to develop and implement training programs that would help gas workers become a part of the clean energy transition by, for instance, becoming certified in the HVAC-refrigerant work associated with the heat pumps that represent a critical component of all the work that is to come.

The timelines proposed by OSE do certainly allow ample space for that training, but the slow roll out of the policy has been another point of contention on both ends of the spectrum.

In the initial draft of the legislation, the first compliance window would have began between 2027 and 2030 for the largest commercial buildings, those with gross areas covering more than 50,000 square feet, then slightly smaller commercial buildings with total floor areas between 20,000 and 50,000 square feet along with all residential buildings over 20,000 square feet would have their first compliance window between 2031 and 2035.

This was an area that both commercial building owners and environmental advocates pushed hard on. Climate organizers were anxious to see the timeline accelerated because of the tight window we have to limit global warming, which requires that we eliminate half of global carbon emissions by 2030 in order to have even the slightest chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) – a world that we will glimpse in the coming years as the ensuing El Niño temporarily raises average global temperatures above that deadly level.

Despite these scientific realities, building owners are more concerned with their bottom lines. So, instead of recognizing the realities of climate change and stepping up to lead, they are doing everything they can to delay action and postpone timelines and fought often to weaken the bill.

In a letter to Mayor Bruce Harrell in March co-signed by the Downtown Seattle Association, NAIOPWA (the primary association representing commercial real estate), and the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, the cosigners outlined what they believe to be the most important actions that the city can take to ensure the vibrancy of Downtown Seattle. Among these recommendations, they urged the mayor to pause and roll back taxes and they encouraged the city not to enact the building emissions performance standard policy in the near future.

The city submitted to pressure from the building owners and delayed the starting timeline by a further three years. Now, under current policies, commercial building owners won’t have to hit their first performance targets until a 2031 to 2035 compliance window, the same first window as those for residential buildings. Under the currently proposed standards, commercial buildings over 20,000 square feet will need to achieve net-zero emissions by 2045, and similar sized residential buildings by 2050.

Sivarajan of Climate Solutions said these delays hurt the policy’s ability to be an effective climate mitigation strategy.

“We are really focused on trying to make sure that it is equitable, effective, and enforceable,” Sivarajan said. “We want to make sure the policy is bold enough to make these reductions. We know that it’s going to get us to net-zero, but we do want to see improvements in the short-term as well. That 2031 start date misses the Green New Deal goal of trying to get to zero emissions by 2030.”

Beyond just pushing to delay the initial compliance windows building owners have tried to extend the length of time they could emit planet-warming carbon. In a letter sent on behalf of downtown building owners to the OSE buildings team on April 12, building owners explicitly recommended that OSE “reduce final compliance target below 100% and/or extend final compliance timetable.” However, OSE has held firm to the 2045 and 2050 final compliance targets for net-zero.

Of course, not all building owners sought to weaken the policy. Affordable housing providers were quite eager to support the policy. “It’s important that the policy move forward, and it’s important that affordable housing providers and low-income tenants are supported with this policy being implemented, and we remain committed to finding solutions to making that happen,” says Patience Malaba, executive director of the Housing Development Consortium, a local association of affordable housing providers that convened an advisory task force around the policy.

Malaba made it clear that the affordable housing community was entirely supportive of the building emissions performance standards because they are collectively committed to achieving net-zero emissions across their respective portfolios. Their commitment stems from a recognition of two factors. First, the climate crisis is affecting and will continue to affect low-income people and people of color first and worst. Second, more efficient and less emitting buildings lead to better living conditions for residents through reduced indoor air pollution, improved heating and cooling, and more resiliency in the case of extreme weather events.

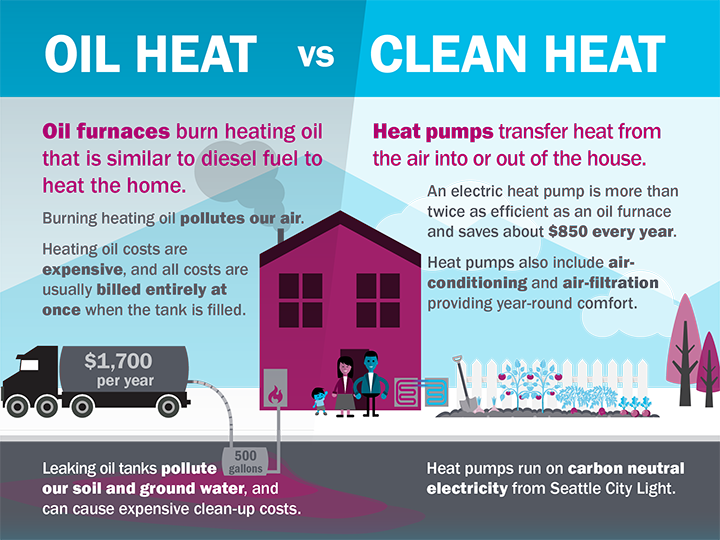

Dylan Plummer, the Senior Representative for Sierra Club’s Building Electrification Campaign, has seen the ample benefits that removing fossil-fueled appliances has both within and around the building. Plummer shared that removing gas-powered furnaces and water heaters reduces indoor and outdoor pollution, which cleans up the air for everyone in the city. But some of the bigger benefits come from installing in-unit heat pumps which, despite their name, both heat and cool.

Because it will encourage installing heat pumps, the emissions policy “helps to incentivize building owners to provide their tenants with access to cooling,” Plummer said, “which is incredibly important at this moment as we’re experiencing more and more days of extreme heat that are actually life-threatening in many cases.”

But whether the heat gets you beat or not, heat pumps have an undeniable benefit that few will balk at. Plummer said, “Heat pumps have such a high level of efficiency that we expect there to be long-term savings both for residents and building owners on their heating and cooling bills.”

Heat pumps also include air filtration systems that help filter out smoke during forest fire season, providing indoor comfort even as outdoor air quality drops. This climate adaptation that could become increasingly vital as the likelihood of major fire events climbs with rising temperatures and more frequent droughts.

These are all benefits that Patience Malaba and the affordable housing community are keenly aware of. Yet, even while affordable housing providers are supportive of this policy and the benefits buildings with net-zero emissions would provide to their tenants, Malaba made it clear that some concerns linger with her and the community that she advocates for, primarily finances.

Affordable housing providers operate on thin margins, which means they have few resources to spare for the building upgrades OSE’s new policy will require.

To alleviate the financial pressure this would impose, the Housing Development Consortium’s advisory task force stated that OSE and the City should provide new sources of funding that affordable housing providers could tap into, and help them access funds from the state or federal government. A response to this concern is built directly into the policy, where any revenues generated through the policy will go towards supporting under-resourced buildings.

There are two potential ways the policy could produce revenue: an alternative compliance payment and fines for non-compliance.

The alternative compliance payment allows building owners to pay a fee based on the social cost of carbon as defined by the State during the first, 2031 to 2035, compliance window instead of decarbonizing their building. Building owners who take this option would pay around $100 per metric ton of carbon that they would be expected to produce during the full five years of the compliance window, and they would also be required to submit a building decarbonization plan that shows how they intend to comply in the future.

The fines, on the other hand, are intended as a penalty for noncompliance and could be levied during any of the compliance intervals if a building misses the targets for the given interval. These fees have been a subject of contention and constantly fluctuated throughout the drafting process.

Given that if a building failed to comply with both the City’s emissions standards and the Washington State energy standards, the owners would be fined twice. With the state’s fine averaging out $2.50 per square foot of building area according to Climate Solution’s Sivarajan and the initial fine for the city’s standards sitting at $5 per square foot, the total fine for noncompliance on both standards would be $7.50 per square foot, which adds up quick for buildings 20,000 square feet and larger. Naturally, building owners were quick to push back on what they felt were punitive fines.

Yet, even in their initial form, environmental advocates were quick to point out that not only were the aggregate fines lower than what has been seen around the country – DC, for instance, has instituted a similar policy with noncompliance fees assessed at $10 per square foot – but beyond that, the fines were still likely too low to incentivize compliance over paying fines among commercial building owners.

Nonetheless, the city lowered the compliance fees first to $2.50 per square foot. But during the subsequent iteration, when they shrunk the number of five-year compliance windows from four to three for non-residential buildings, meaning that instead of having 20 years to reach net-zero, building owners would only have 15, which means faster decarbonization over a shorter period of time, they also raised the fees from $2.50 per square foot to $3.33 per square foot for non-residential buildings while keeping residential fines at $2.50. While this at face value is an increase in the fines, the reality is that – if a building or portfolio were to fail to comply during every single window – it averages out to be the same.

Whether this fee structure is sufficient to encourage compliance is something that Kocher and his colleagues at the RMI will be assessing in the coming weeks as the OSE wraps up their draft legislation and sends it out for review under the State Environmental Policy Act.

Once that review is completed, the policy will be forwarded to the City Council for deliberation and consideration. The council process will be the best time for residents to get involved and give feedback. While there are not yet any definitive dates or times for hearings, there will no doubt be several opportunities going forward over the coming months for you to get involved.

The Sierra Club, 350 Seattle, and Unite Here Local 8, who have all been involved in advocating for the policy, will start a canvassing campaign to raise awareness and get people prepped and ready to testify before City Council as they start their process later this year. Follow the Sierra Club Seattle Chapter and 350 Seattle for updates and opportunities to volunteer. The Urbanist will continue to track this legislation as it works its way through the process and implementation.

Since most of our buildings will be around for many decades to come, the future of our built environment is being determined by policies like these. So make sure to follow along and get involved.

Syris Valentine is a Seattle-based writer and journalist primarily focused on climate solutions, social justice, and the just transition. Their work has appeared in The Atlantic, Grist, High Country News, Scientific American, and elsewhere, and you can follow them @ShaperSyris on social media and through their newsletter, Just Progress.