Early signs point to the new city council hand-wringing over housing solutions.

Seattle got its first look at how its new city council, largely composed of centrist newcomers, would handle housing issues as the land use committee held a hearing last Wednesday on Councilmember Tammy Morales’ proposed “Connected Communities” pilot program. The proposal would set up zoning incentives for projects that set aside 30% of units as affordable and partner with community-based organizations. The bill faced a gauntlet of questions and concerns from Morales’ new colleagues.

Public comment was mostly in favor of the proposal, although some opponents did emerge. While affordable housing providers and advocates and climate and racial justice organizations testified in favor of Connected Communities, some representatives from tree groups and neighborhood activists came out against the bill, which they argued posed a threat to tree canopy despite the fact that under the pilot, 35 properties at most can be developed.

Professionals in the affordable housing industry pointed to the added opportunities the bill would open up. Among them was Jesse Simpson, policy manager for the Housing Development Consortium (and also a board member at The Urbanist).

“For far too long, exclusionary zoning codes have restricted where people can build and live in affordable housing across our city,” Simpson said. “We think that the Connected Communities pilot is a great step towards establishing more equitable zoning across the entire city, allowing more homes especially affordable homes to be built in neighborhoods across Seattle. The pilot creates land use incentives to encourage the kind of development we want most; it creates a pathway to leverage the ability of private developers to build affordable housing in partnership with community-based organizations.”

Neighborhood and tree advocates, meanwhile, called the bill an end around of the Seattle comprehensive plan that was out of scale with residential neighborhoods and proper tree canopy provision.

“I’m concerned that these projects have no room for any trees or green space, and with five-foot setbacks, even street trees will have to be very thin,” said Sandy Shettler, with the tree preservation group The Last 6000. “Why are we targeting frontline communities with high hardscape housing when they already have huge canopy deficits?”

Meanwhile, tree activists have been recently focused on preserving a single cedar tree in Wedgwood, a neighborhood where racial covenants were imposed when the area was first subdivided in the 1940s, with original developer Albert Balch advertising Wedgwood as a “planned and restricted neighborhood” as late as 1955.

Morales, who is the newly installed chair of the land use committee, said she intends to vote the bill out of committee on March 21. She has scheduled another briefing on the bill for March 6.

Morales unveiled her equitable development pilot program in September, but the previous iteration of the council ultimately tabled the bill. At the moment, the legislation before council is very close to the version we broke down in September, so check out that explainer for a full rundown on the bill’s nuts and bolts.

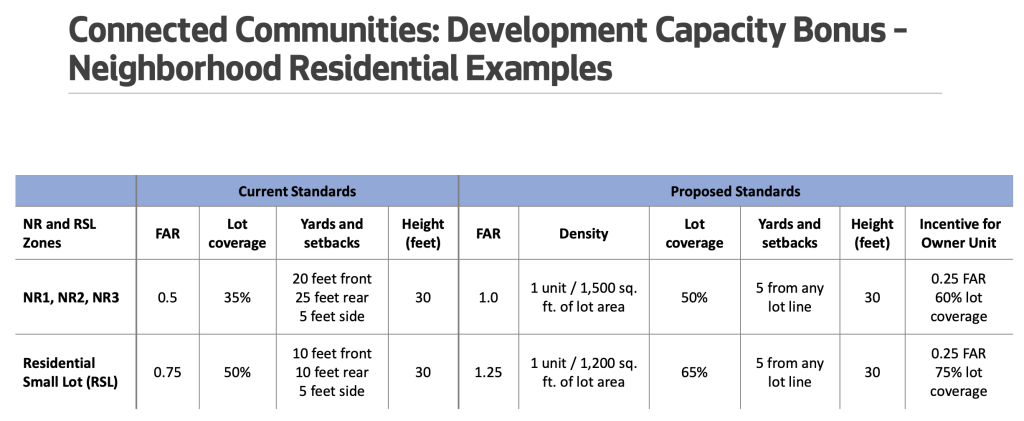

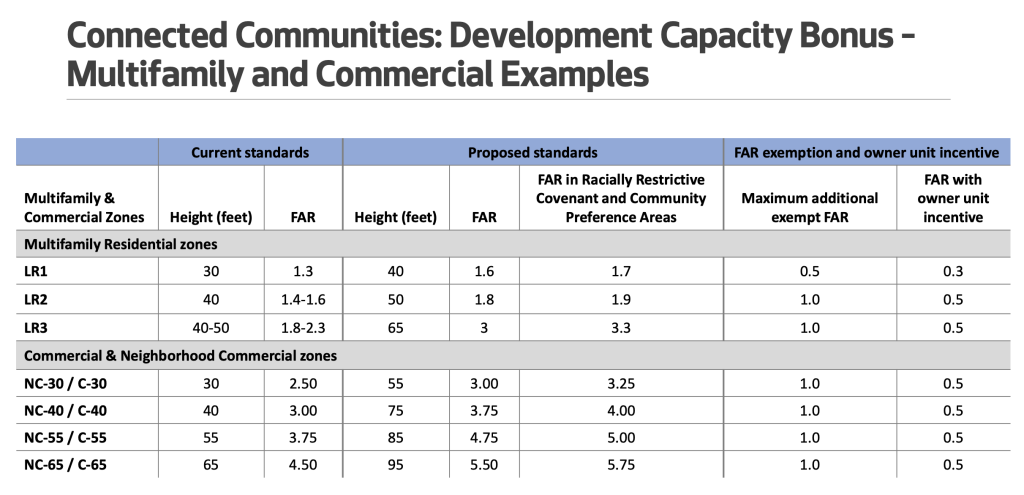

In short, Morales’ legislation would offer nonprofit organizations and public development authorities a new pathway to achieve substantial density bonuses and establish community-oriented services. Eligible projects would be able to use those new density bonuses and zoning flexibility in the city’s myriad Neighborhood Residential, Multifamily, and Commercial zones. The affordable requirement is for at least 30% of the units to be affordable at 80% of area median income (AMI) or lower. The pilot program would end by 2029 or after 35 qualifying projects have applied, whichever is earlier.

However, comments from other councilmembers suggests some amendments could be on the way — or that the bill could be dead on arrival. Two new members of the land use committee — Tanya Woo and Maritza Rivera — expressed serious concerns with the legislation. Cathy Moore did not share her position, but has generally aligned with her fellow newcomers thus far.

Morales makes her pitch

Reintroducing her bill at the hearing, Morales said it would further the idea of a 15-minute city, in which residents can meet their basic needs within their immediate neighborhood, and would address five critical needs facing the city.

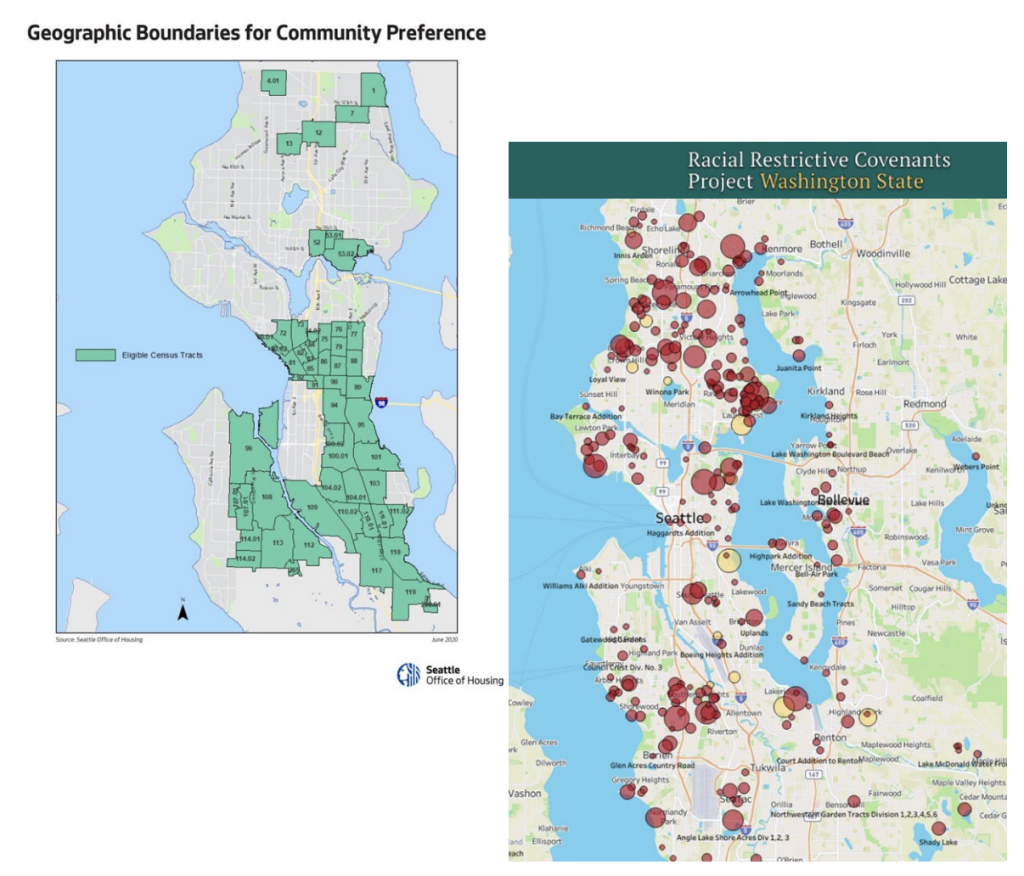

“The first [need] is it would address the harmful history of redlining and racial exclusion in Seattle by providing substantial incentives for development in areas that are touched by these harmful practices across the city, allowing affordable housing construction in parts of the city where no affordable housing has been built before and in areas of high displacement risk,” Morales said. “Second, it addresses the exclusion of low-income communities and promotes social cohesion by setting a high minimum threshold for inclusionary zoning on these 35 parcels. It would require a substantial amount of affordable housing and projects that would otherwise likely be 100% market rate or higher.”

The third and fourth critical need Morales cited was building generational wealth in marginalized communities and helping those communities stay rooted in place, in part by providing incentives for developers of all stripes to partner with community organizations based in those areas. Finally, the program aims to increase access to cultural amenities under the 15-minute city concept.

“And fifth, it brings community-serving small businesses and essential services to more parts of the city through inclusion of ground floor equitable development uses, which allows more people to access culturally relevant essential needs by traveling downstairs from their building, for example, instead of having to get in their car to drive somewhere,” Morales said. “In exchange for these potential uses, developers would receive a proportionate amount of corresponding incentive they could receive for floor area ratio and height bonuses, standard practice for incentive programs in the city.”

Woo and Rivera raise concerns

After receiving public feedback, Morales also fielded a wide range of questions from her colleagues on council. Tanya Woo, Council’s newest member, in particular had plenty of questions and concerns.

For starters, Woo worried that it was too easy to qualify as a community organization and potentially secure the Connected Communities incentive. Donald King, a Black architect with the Nehemiah Initiative Seattle who lobbied for and secured similar legislation providing incentives to churches that develop affordable housing on their properties, responded to the effect if more people got into affordable housing production, “what’s the harm?”

Woo worried the bill was too vague and left too many provisions as optional, but Morales offered a crash course into how to draft a bill that does not overstep councilmanic authority and veer into the purview of the executive branch. She explained that’s why the bill was drafted with “council request” items rather than outright requirements, which wouldn’t have been legally binding where they overstepped.

Woo argued for deeper affordability than the 80% of AMI offered in the draft, but the assembled panel of affordable housing builders made the case that, while need at the extremely low income (below 30% AMI) segment is the most acute, an effective housing strategy would need to provide housing across a gradient of incomes. In short, that the middle band of affordability should not be forgotten.

“So what we’re looking for here is a broader spectrum of affordability for a broader spectrum of our neighbors because so many of our neighbors are leaving,” Morales said. “And this is impacting our businesses; it’s impacting our community vibrancy. It’s impacting our ability to have neighborhoods that are and particularly individual buildings that are more than market-rate or, you know, only for folks who are very low income.”

Even so, Woo seemed interested in requiring deeper affordability with the pilot program.

Councilmember Dan Strauss noted that in 2021 Council had to pass the religious bonus bill twice after their decision to lower the affordability requirement on the bill passed at the last minute via a walk-on amendment ended up killing the economic feasibility of several projects and caused the very groups that lobbied for it to oppose the final version of the bill. In other words, properly calibrating incentives to create feasible projects and not pushing unvetted last-minute amendments that could jeopardize them was important, Strauss argued.

Councilmember Maritza Rivera, meanwhile, was dubious on the idea of pilot programs in general.

“We’re adding a pilot program, and the truth is, the City has yet to add a pilot program that it actually sunsetted in — I don’t know — however long,” Rivera said. “I don’t think of these things as really a pilot program because we’ve never completed any. So the truth is, you know, who knows how long this will last?”

Rivera expressed concerns that the City had too many affordability programs and it was becoming a burden for staff and council to oversee them. She seemed to hint at hitting pause until new members got up to speed and conduct an evaluation of existing programs. The city council spent all of January off from committee meetings where they might have gotten official briefings on how those programs work.

“So we’re all trying to come up to speed with all of those programs,” Rivera said. “And so this is another program on top of the ones that the city does administer that we really need to dig into. I think there’s a level of discomfort to start a new project where we’re not clear on how well the existing projects and incentives that we’re currently doing at the city are doing, so I want to be transparent and honest about that.”

Where the new legislators will land once they get up to speed is still uncertain. The fact that Morales now composes the vanguard of the left flank of city council could mean her bills get added scrutiny from a council now dominated by centrists.

If Woo does in fact gut or block Morales’ bill, it could cement a rocky relationship between the two. Woo ran against Morales but lost a close District 2 race in November. However, with strong support from council newcomers, Woo won an interim appointment to fill the vacancy created by Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda winning higher office at the King County Council. Ahead of the vote, Morales criticized the decision to appoint her challenger, saying it broke from the collaborative spirit the members have often invoked. Nevertheless, they proceeded.

The Connected Communities pilot program will be another testing ground for promises of collaboration and goodwill.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.