My journey to urbanism took a twisted path. I grew up in rural Kitsap County, studied forest ecology, and worked in the woods of Alaska, Washington, and Oregon for 10 years in outdoor recreation and biology for the Forest Service, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, a public utility, and a consulting company. My passion was the mountains and streams. But somewhere along the line I realized that the biggest threats to wild lands are not in our rural areas, but in our cities and their sprawling suburbs. And to save our forests and farms we must build denser, more walkable communities. So I went back to school for architecture and have been designing and advocating for urban housing ever since.

It is because of my background working in the forest that I find efforts to use the cover of savings trees to stop housing so misguided. This was brought to a head by recent efforts to use one large cedar tree slated to be cut down by a shortsighted developer to undo the compromise tree legislation, legislation that was supported by The Sierra Club and Habitat for Humanity. A recent op-ed in The Urbanist laid out the case to save a tree called Luma and made a call to revise the legislation. But undoing the legislative compromise that was years in the making, even for minor adjustments, may open the floodgates and end up doing more harm than good.

Before I go on I want to acknowledge the beauty, power, and benefit of urban trees, particularly majestic old ones such as Luma. I recently moved from a nearly treeless street in Othello to 15th Avenue S on Beacon Hill and the biggest change may be the effect that the wonderful street trees have – the shade they provide, the visual calm they create by their presence. As a city we should be planting more trees along our streets and rights of way, our parks and yards. But we should not be using trees as a smokescreen to stop building new urban housing, which is one of the most positive things we can do for the climate.

Some tree advocates claim they support housing but have opposed any compromises that would do so. A recent Investigate West hit piece authored by Eric Scigliano describes the city council listening to both tree advocates as well as homebuilders as a seemingly nefarious conspiracy. Many of these tree advocates have vehemently opposed efforts to ensure that the scarce land we have zoned for multifamily housing, which produces the vast majority of our city’s new housing, can actually be used for homes. That’s what their push to strip minimum lot coverage (85% in townhouse zones and 100% in more intensive apartment zones) would do. The labyrinthine tree bureaucracy proposed instead would slow and stop new housing. The minimum lot coverage allowances are key to making sure housing projects can go forward in a difficult economic climate with high interest rates and high construction costs.

As we all can see, there are not a lot of flat, empty sites in the city. Nor cheap ones. There are a lot of programmatic and regulatory requirements that inform how housing projects are laid out including access, waste storage, stormwater management, accessible routes, amenity areas, utility connections, car and bike parking, required setbacks and separations, height limits, and more. And this is to say nothing of the challenge of ensuring good design that provides future occupants and neighbors with the best access to light and air while maximizing their privacy. With all these constraints it is often not as simple as adding another story or shifting the building on the site.

And without these crucial exemptions in the tree ordinance many parts of our city would become non-viable for new homes and any hoped for change under the new comprehensive plan, such as allowing greater density in Neighborhood Residential zones and the new Urban Villages planned near the 130th and 145th Street Link stations, would struggle to produce housing.

What’s actually in the tree ordinance

Even as they complain, tree activists have gotten a lot of what they wanted in the new law (as they admit in the Investigate West article) which I think is what compromise means. And let me be clear, the new law is not a giveaway to developers because it makes it harder and more expensive to build housing in Seattle by adding process and fees to any project with a tree on site. If homebuilders are celebrating, it is because they averted a disaster. The new law has many components that seek to strike a delicate balance.

Some highlights from the new tree ordinance are:

- Require trees removed to be replaced onsite if they’re removed for development or requires a fee be paid to plant and maintain trees in under-treed areas. The fee is $17.87 per square inch or about $8,084 for a 24-inch diameter tree, and $2,800 for tier 3 trees. There is currently no fee for cutting tree, nor a replacement requirement.

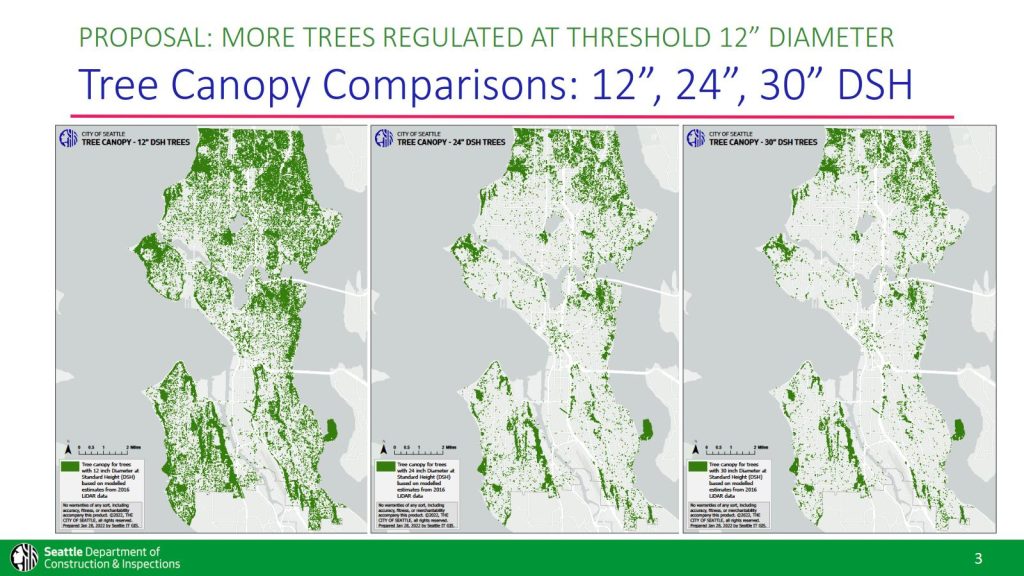

- Expands protections to a total of 175,000 trees across the City; the previous code only protected approximately 17,700 trees.

- Significantly restricts tree removals on Neighborhood Residential lots, where much of the city’s canopy loss has occurred:

- Near absolute restriction on the removal of Tier 1 (Heritage) Trees.

- Prohibit removal of a Tier 2 tree for any reason other than construction or safety

- Lowers the size threshold for Tier 2 trees from 30” to 24”.

- Lowers the number of Tier 3 (Significant) trees that can be removed to two trees every three years.

- Requiring new developments to include street trees in their plans, including in Neighborhood Residential zones where it was previously not required.

- Increases penalties for illegal street tree cutting.

- Expands Seattle Public Utilities (SPU)’s Trees for Neighborhoods Program that has already helped Seattleites plant more than 13,400 trees in their yards and along the street.

- Creates additional penalties for unregistered tree service providers.

Seattle added 92,000 residents with minimal loss of canopy

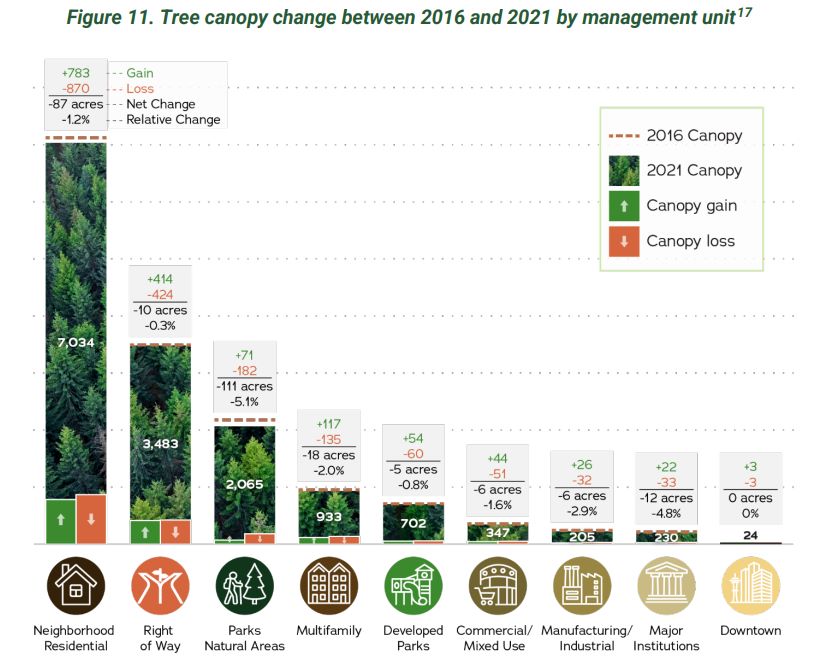

The advocates for trees like to point to the 2021 Canopy Assessment as justification for the pages of new rules and fees. In fact, Scigliano quotes tree-truthers who insist that canopy loss figures were somehow an undercount. The City’s report finds that between 2016 and 2021 the city lost 255 acres of tree canopy or about the area of Green Lake. But of that 255 acres, 126 were lost on city land including natural areas (111 acres), parks (5 acres), and rights of way (11 acres) leaving only 129 acres that could be due to development.

What they fail to mention is that over that same time period the city netted 42,836 new homes (46,947 new homes – 4,111 homes demolished) and grew by more than 55,600 residents, jumping from 686,800 to 742,400 according to the Washington State Office of Financial Management. By April 2023, Seattle’s population had rebounded from the pandemic and hit 779,200 — an increase of 92,400 residents since 2016.

Is there anywhere else in the state where you add almost 100,000 people in less than a decade at the cost of just 129 acres of canopy cover? Seattle can support population growth like nowhere else in the state and failing to do so — even for seemingly noble goals like strict tree protections — will lead to carbon-intensive sprawl development and destruction of forests and resource lands on the edge of the urban growth area. It will mean more trees destroyed overall.

These are urban homes, near transit and services, where people will be far more likely to walk, roll, bike or take transit; to have one car or no car instead of two plus as is common in the suburbs. They are, in many cases, homes with shared walls and floors that make them more energy efficient. In almost every project new street and on site trees are added as required by the city, which is one of the only ways many areas get new trees. They are also in a progressive, diverse community, where abortion is legal and being gay or trans or a refugee is not a crime. In what is becoming a more extreme and scary America, this is a place that should be welcoming folks, not closing the door.

Pushed out of urban core, growth wipes out exurban forests

Now that we’ve looked at the tradeoffs within the city, let’s look at the alternative way we add housing if we cannot build it in Seattle. Rural Kitsap County, just a ferry ride away from here and where I grew up, is experiencing a housing boom, and it is a tree slaughter. Let’s look at one example, the Blue Fern Platt outside Silverdale. It composes 93 acres of forest that will soon be mostly clearcut to build 500 homes with 1,250 parking spaces. This one project is almost the equivalent to half the canopy Seattle lost due to development and it’s adding 500 homes, not 55,000. These homes are far from transit, jobs, and necessities and are expected to generate 4,729 new car trips per day.

The fewer homes we add to our city the greater the pressure there is to clearcut our regions forests and pave over the farm fields. And at the density of this development, about 5.3 houses per acre, it would take 10,490 acres or about 41 Green Lakes to build the housing Seattle built from 2016 to 2021.

With all this in mind, I would ask: What is better for our environment and society, building more dense housing in our existing transit and amenity rich urban neighborhoods, sometimes at the cost of a tree? Or is it prioritizing every tree in our city over housing for people and pushing new development to the suburbs and farther into our rural areas? I know my answer. Sometimes saving a tree is sitting in an old cedar and putting your body on the line, and sometimes it is standing up for housing in order to save a forest somewhere else.

Patrick grew up across the Puget Sound from Seattle and used to skip school to come hang out in the city. He is an designer at a small architecture firm with a strong focus on urban infill housing. He is passionate about design, housing affordability, biking, and what makes cities so magical. He works to advocate for abundant and diverse housing options and for a city that is a joy for people on bikes and foot. He and his family live in the Othello neighborhood.