The overhaul makes way for 3,000 homes, but a SoDo Makers District with 900 homes didn’t make the cut.

On Tuesday, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell signed industrial land reform into law, capping a lengthy process of study, outreach, and debate, spanning at least three mayoral administrations.

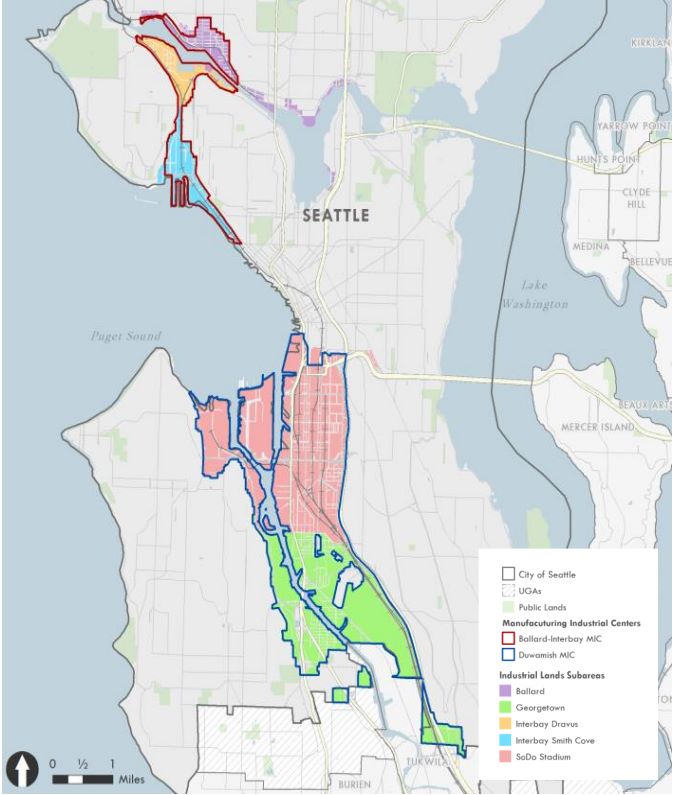

The land use code updates will strengthen “protections for existing industries, allow flexibility for future growth near planned Sound Transit light rail stations, and create healthier transitions from industrial to non-industrial areas,” the Mayor’s office said in a press release “The updates are estimated to create 35,000 new jobs and 3,000 new homes over the next 20 years.”

“Our maritime and industrial lands are a unique, vital, and historic asset that strengthen Seattle’s economy and provide pathways to thousands of living-wage union jobs in our city,” Mayor Harrell said in a statement. “The policy leads with our values of inclusivity, equity, and innovation and sets the groundwork for the Seattle we want to see: a thriving city with diverse employment opportunities and vibrant, affordable places to live, work, and play.”

Harrell’s signing ceremony included representatives from the Port of Seattle, labor, housing partners, and maritime and industrial businesses. Many of Seattle industrial zones abut Port of Seattle facilities from huge container terminals in Elliott Bay to Fishermen’s Terminal on Salmon Bay.

“We have a green light for workforce development and jobs,” said Toshiko Hasegawa, Port of Seattle Commission Vice President. “We appreciate Mayor Bruce Harrell’s careful work brokering a compromise with stakeholders from around the state and Councilmember Dan Strauss’ leadership at the Seattle City Council. The compromise legislation advances our economy by protecting the city’s highly productive industrial zones, and also benefits the community by preventing any new conflicts between our most active industrial zones and residential areas. This is a win for economic diversity, resiliency, and Seattle’s future.”

What’s in the industrial land reform?

The thrust of the reform is to allow greater density of industrial uses and some increased mixing of uses, while weeding out unwanted uses like big box stores and self storage that have encroached on industrial zones and squandered real estate that had been intended for industrial businesses that generate more jobs with higher wages. Check out Ray Dubicki’s primer for a closer look at what the legislation does or give a listen to The Urbanist Podcast episode on industrial reform.

The legislation creates three new industrial zones:

- Maritime, Manufacturing, and Logistics: “This zone will enhance protections for both core and legacy industrial or maritime areas and help prevent big box retailers or mini-storage facilities from being built in these zones,” the Mayor’s release states. “This is particularly important for areas on or near the shoreline, as well as for locations near port and rail infrastructure.”

- Industry and Innovation: “This zone would encourage new development in multi-story buildings that accommodate industrial businesses mixed with other dense employment uses such as research, design, offices, and technology through a system of density bonuses. Modern industrial development would support high-density employment near Sound Transit light rail stations and commercial areas. ”

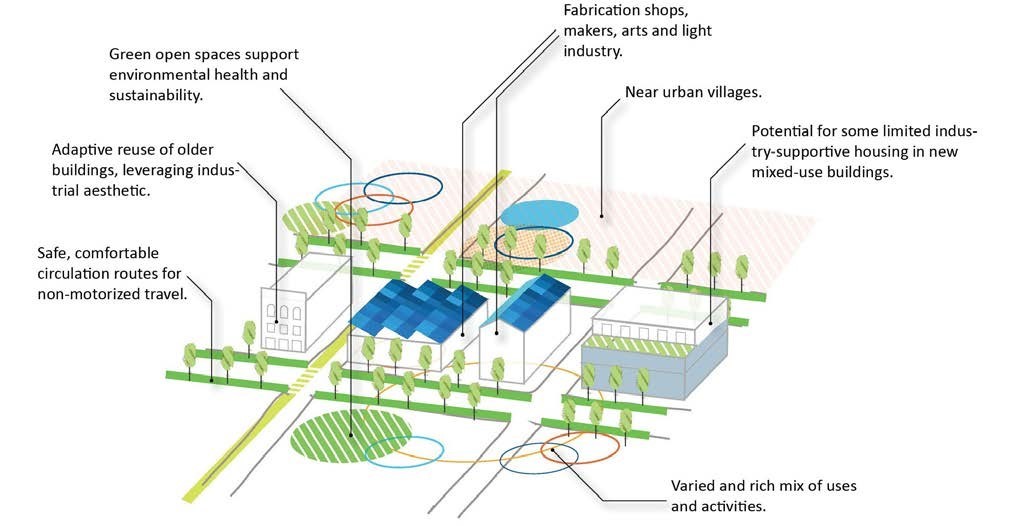

- Urban Industrial: “This zone would aim to increase employment and entrepreneurship opportunities with a vibrant mix of affordable, small-scale spaces for light industry, makers, and creative arts, as well as industry-supporting ancillary retail or housing spaces to create better, integrated, and healthier transitions along the edges between industrial areas and neighboring urban villages, residential, and mixed-use areas in Georgetown, South Park, and Ballard,” the press release states. (In other words, the brewery-topping apartments of Ray Dubicki’s dreams.)

Port squashes SoDo Makers District with capacity for 900 homes

In her statement, Hasegawa alluded to the fight that emerged at the end of the process over allowing more housing in SoDo near Port of Seattle operations. Proponents say the “Makers District” could add 900 homes along 1st Avenue S near the stadiums, adding workforce housing and street-level makers spaces, injecting some vitality into a neighborhood that tends to deaden quickly in-between event surges.

The Port of Seattle campaigned hard against this move and prevailed in getting its way, even as the decision cleaved the labor community in two. While the Port and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) Local 19 opposed the Makers District, several other unions supported it, including Unite Here Local 8 and the Seattle Building and Construction Trades Council. Monty Anderson, the executive director of the council, testified in favor in earlier committee meetings.

“The original EIS (environmental impact statement) that they did said that housing was OK there,” Anderson told KOMO, “The mayor’s team kind of took it out.”

Councilmember Dan Strauss, who chairs the land use committee, said he was open to revisiting the decision at a later date, but didn’t want to tank the legislation by adding the Makers District provision and upsetting key stakeholders.

“Mayor Harrell and his team crafted a balanced proposal that protects both our maritime and industrial lands while supporting the flexibility needed to keep up with emerging industrial needs,” Strauss said in a statement Tuesday. ”Our maritime and industrial businesses buoy our economy in downturns and remain a vital part of our city’s fabric. When looking at Fisherman’s Terminal, every fishing vessel you see is a small business directly employing hundreds of people, and indirectly thousands in our community. I am thankful for the additional protections this bill provides to the lands that support these workers and many other family-wage industries.”

The Port’s argument was that SoDo was an inappropriate location for housing growth — in large part because of dangerous, polluting traffic generated by its container port — won the day.

“Some argue that if you oppose rolling back land use restrictions then you are opposing housing development in the midst of a housing crisis. In fact, the Port has never been more vocal in support of housing,” Hasegawa and fellow Port Commissioner Ryan Calkins wrote in an op-ed in The Stranger. “We see the impacts on our workforce of sky-high housing costs and have been advocating or greater density in the city and region with our colleagues on the Council and in the Legislature. But the proposed area is no place for affordable housing. Families deserve better than being surrounded on all sides by freight arterials, a 40-minute walk from the nearest playground, and no grocery stores or schools.”

The Port referenced the fundamental argument for segregating port facilities and heavy industrial uses away from residential uses — namely that industrial business is often loud, stinky, and generates heavy truck traffic that pollutes heavily and poses a danger to other road users.

“Are we listening to the folks of Allentown, Tukwila, who experience nonstop freight traffic in front of their homes?” Hasegawa and Calkins asked. “Or people from West Seattle, who are bothered by the noise of train sounds through the early hours of the morning? Or neighbors in near-airport neighborhoods, such as Beacon Hill, who experience regular flights overhead?”

Future fights between freight interests and urbanists

Lost in this eleventh hour argumentation is a clear sense of obligation to mitigate the harms the Port and associated industries generate. Hundreds of thousands of people live in the flight path of the airport and deal with noise on a daily basis and countless thousands live on heavy haul freight routes serving traffic headed to the port and breathe in pollution that shortens their lives and increases the risk of being injured or killed in a traffic collision.

Due to racist land use decisions of the past and socioeconomic jockeying that continues to this day, people living in those communities are more likely to be Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. Chinatown-International District and Pioneer Square — two densely populated neighborhoods with lots of low-income residents of color — are already just a few blocks from the proposed Makers District. Those residents already live with those harms.

The region needs a port and an international airport to function, but the debate that “saved” 900 families from living near the port, sparing them from pollution and traffic violence, ended up highlighting how many families won’t be saved because they already live near industrial pollution — plus the inadequacy of the Port’s efforts to mitigate that pollution and traffic violence.

The Port and the Freight Advisory Board have opposed bike lanes through SoDo even as Port commissioners lament the danger as SoDo emerges as Seattle’s biggest hotspot for deadly crashes. If we were farther along in improving safety and reducing pollution on freight corridors, perhaps it wouldn’t be so unfathomable and sacrilegious to put housing in SoDo or other neighborhoods on the edge of industry or port facilities.

While it has tried to do better lately, the Port was a key player in decisions that locked in a car-centric design to the new Seattle Waterfront even as environmental leaders and urbanists (including Cary Moon and Mike McGinn) fought to replace the Alaskan Way highway viaduct with transit, bike, and pedestrian improvements rather than a four-billion-dollar highway tunnel, a surface highway that is nine lanes at its widest, and a new four-lane bypass connector — all of which somehow manages to leaves a hole in the bike network and transit network. The Port has raised questions about a proposed highway removal in heavily polluted South Park and has also lobbied to add and expand urban freeways in the 21st century in the name of quicker access to to its sister port, the Port of Tacoma, with the long-envisioned Puget Sound Gateway project that is set to worsen pollution in communities of color.

To put an ironic cherry on top of the Makers District saga, the Port gave its blessing — albeit half-heartedly — to allowing hotel developments in the Makers District, which was already ramping up with several additions near the SoDo stadiums. So while the port might conceivably save a few local residents from traffic crashes on its heavy haul corridors, it’s open season on tourists.

The potential addition of 900 homes in SoDo will not make or break the region’s massive housing crisis. However, the larger issues exposed by this debate about mitigating pollution, freight traffic, and industrial uses will have a huge bearing on the region’s ability to provide safe, healthy housing in sufficient quantities to meet the needs of the working class, who are expected to work in those industries but with increasingly few places where they can afford to live.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.