For over a year, committees of local business and labor representatives have been working to develop a strategy for Seattle’s industrial and maritime lands. Given a pandemic and some other stuff going on in the city, it wasn’t a particularly high-stature initiative. In many ways, dozens of meetings over 18 months went by without notice. And though the outcome will have direct impact on the lives of every person in the region, there were very few announcements for participating in the discussions. That the outcome was announced on the last day of June, a Wednesday between a historic heat wave and the Independence Day holiday, says a lot.

The newly released Industrial and Maritime Strategy produced in these meetings is actually 11 strategies in three strategy categories. They cover investments in workforce and transportation, protections for land uses and buffers, and focused actions in unique places and circumstances.

From this strategy of strategies, the Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) will author an Environmental Impact Statement to study land use changes. The land use changes will focus on big spaces, small spaces, dense spaces, arts spaces, flexible spaces, and ways to “strengthen the future of maritime, manufacturing, and industrial areas.” There will be a specific look at Georgetown and South Park to match neighborhood goals with lodging near the stadiums.

The press release announcing the recommendations promises that this new industrial and maritime strategy will “renew commitment to Seattle as a maritime and manufacturing city.” Commitment is the right word, because it takes that kind of blind devotion to believe these strategies will do much. Many are the same tools that have been Seattle policy decades — keep the jobs where they are and get people to them. The futility is that the strategies ignore the changing industrial and urban landscape.

And that’s fine for Mayor Durkan. Like so much else in the waining days of this administration, Seattle’s Industrial and Maritime Strategy is a punt to the next mayor.

The Blank Parts of the Map

As we noted when the mayor assembled the Industrial and Maritime Strategy Council, the voices in the meetings weighed heavily towards Manufacturing Council representatives and stadium interests, with legacy industries like fishing and modern work like breweries and cannabis relegated to the sidelines.

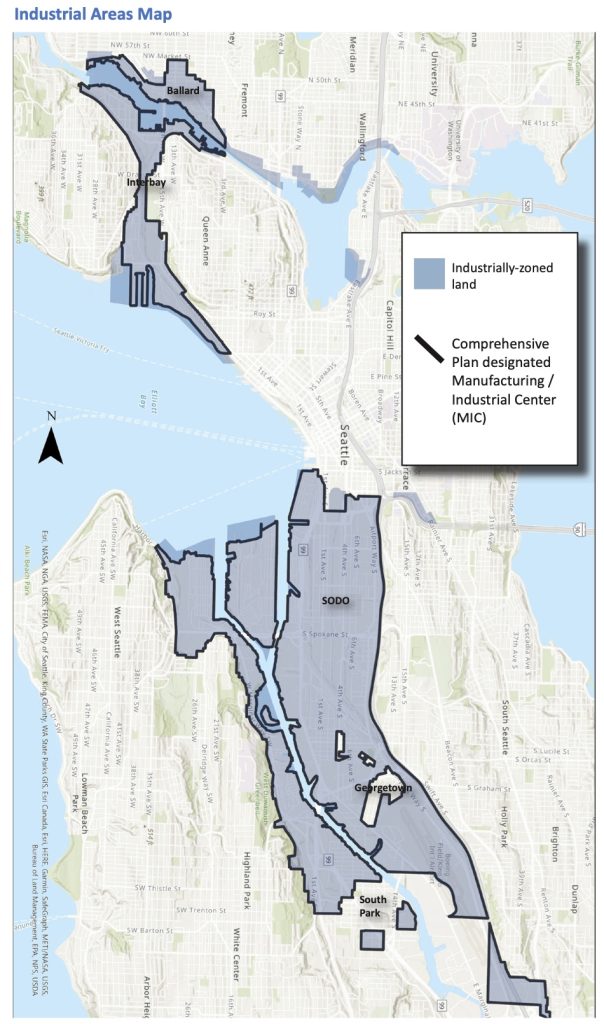

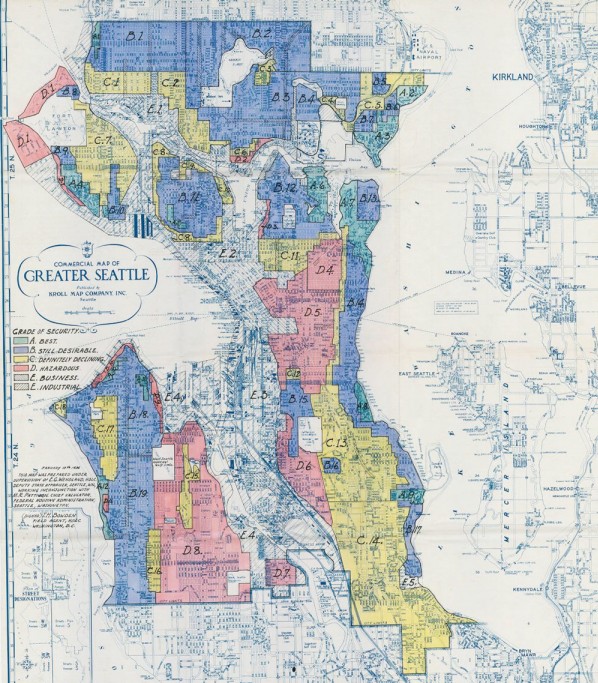

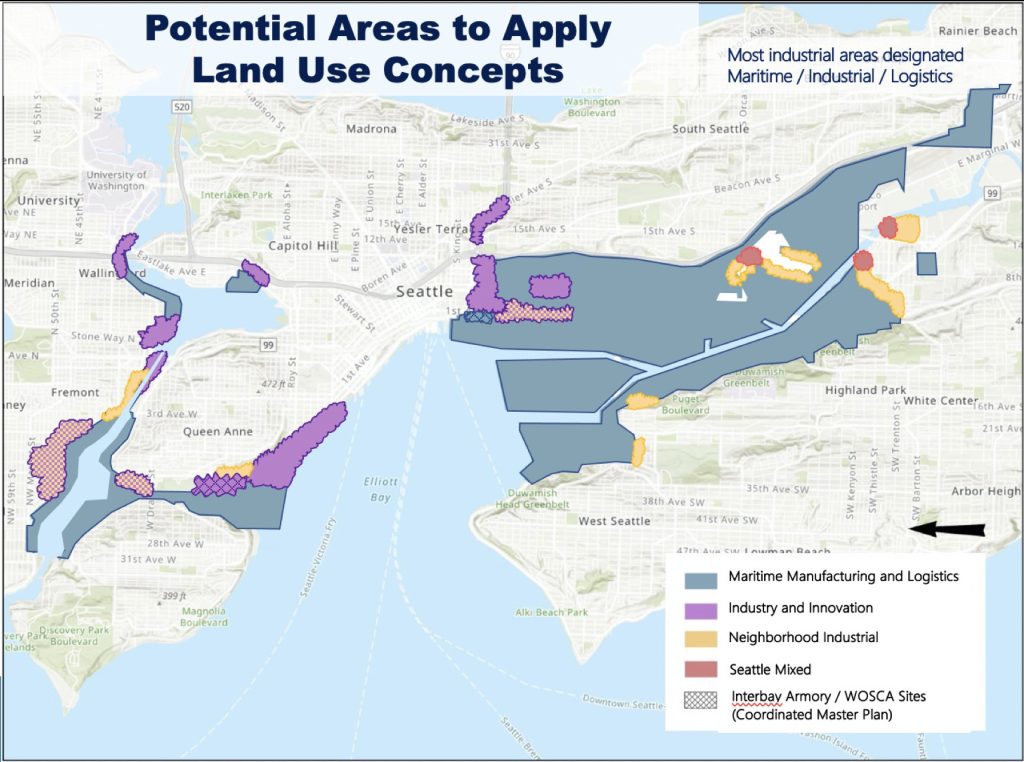

With such a limited room, the strategy is equally limited to tinkering at very narrow edges. We can start with the map used to show the city’s industrial lands. As with every other land use issue in this city, this is the exact same map as the 1930’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation maps that redlined the city. The white (uncolored) areas on those 90 year old maps are still the industrial areas shown on the maps used in this strategy. Right off the bat, the Industrial and Maritime lands proposals perpetuate systemic racism.

Seattle’s Industrial lands from the 2021 Industrial and Maritime Strategy (Seattle OCPD)

Seattle’s industrial lands (uncolored) shown in this redlining map from 1936. (Map by Knoll Company)

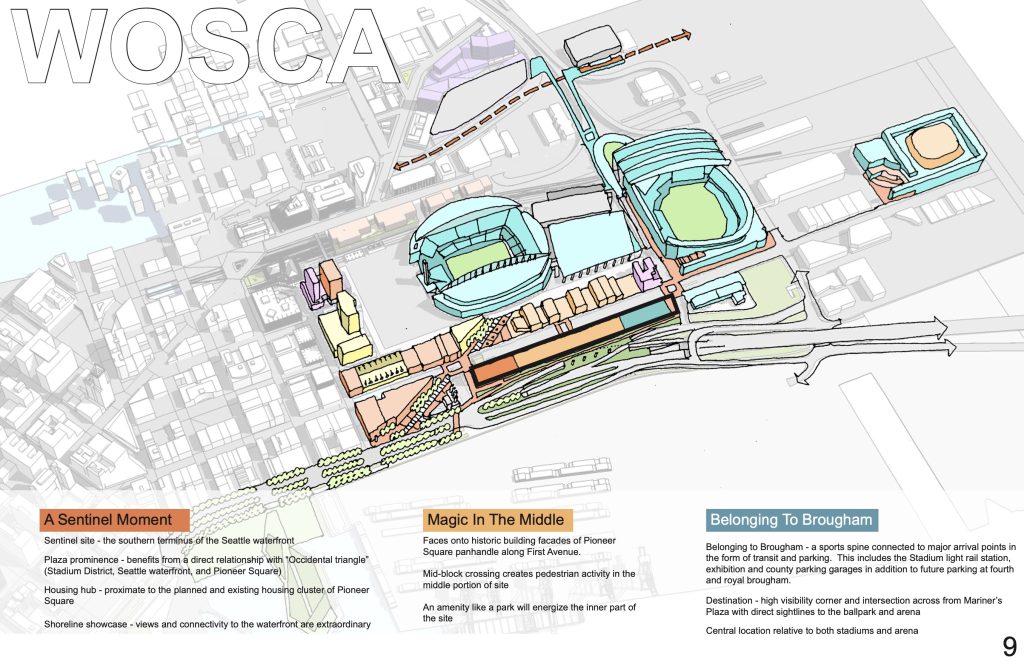

One of the sites that’s called out in the industrial and maritime strategy is the WOSCA site near Lumen Field and it encapsulates the problem with the thinking in these strategies. WOSCA is the blank and empty shipping warehouse between the football stadium and the SR-99 tunnel’s south entrance. It could make a nice complex of buildings that matches the King 5 headquarters and offers some cool gameday experiences. It’s been the subject of reports and studies and sketches and now it finds its way into the current industrial and maritime conversation by name.

The WOSCA site analysis doesn’t just slice the sides of First Ave into different neighborhoods, it slices the 120-foot wide by 1,400-foot long site into three different flavors, each given a name and height limits and aspirational domains. Then this whole analysis gets sucked up into a citywide strategy and we can’t figure out why fishing businesses are being replaced with mini-storage.

Seattle is 53,000 acres. The WOSCA site is four. That today’s “Citywide Industrial and Maritime Strategy” calls out 0.007% of the city’s area for special focus is a level of micromanaging detail that Steve Jobs looks at with envy. But this isn’t a bevel on an iPod or even missing the forest for the trees. It is a deliberate myopia.

Look at the industrial lands map again and appreciate what it does not show. By focusing on just the industrially zoned land, the map misses how industry fits in the city today.

This industrial lands map ignores downtown. Industry lies on either side of the densest part of the city, and focusing on the industrially-zoned areas misses how Interbay and the Duwamish tie together through the center of the city. The transportation network, including regular freight trains, pass under and through downtown. Downtown has actual industrial uses, including breweries, cannabis shops, and some tiny little farmers market. In the reverse, there is a chain of Fortune 500 company headquarters that spread into the industrial areas from downtown. Expedia’s in Interbay. Amazon, Nordstrom, and Expeditors International line up along 5th Avenue. Weyerhaeuser is in Pioneer Square and Starbucks is in SODO. There’s no wall between downtown and the industrial neighborhoods, regardless of what the map shows.

This industrial lands map ignores neighboring communities. The wind doesn’t stop at those zoning boundaries. Seattle has never come to terms with the ways our zoning map impacts health of the Black communities on the other side of the highway, or ways those highways pushed the center of the region’s diversity just over the city line. Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities and women do get lip service in this report, but in the form of targets for job training in the growing industrial work. There’s no recognition that the city’s policies supporting industry with polluting highways had a strong hand in setting up the situation where these supports are needed.

This industrial lands map ignores most of the city. One of the biggest threats to industrial land in Seattle is, of all things, grocery stores. Industrial zones have some of the only parcels in the city that are big enough to fit a modern grocery, that’s why Interbay has six of them including Grocery Alley. Talking industrial land without showing where grocers are in the rest of the city — or improving zoning elsewhere that could be more attractive to grocery stores — misses an important strategy to preserve industrial land. Groceries are just the most noticeable example. There are plenty of uses that are relegated to industrial spaces that fit in neighborhoods. We can preserve dedicated industrial lands by welcoming more neighborhood industrial uses like commercial kitchens and gyms and breweries into residential areas.

The industrial lands map ignores the larger region. As every other part of urban life has spilled across the city’s boundaries, industrial and manufacturing has too. Seattle’s industrial lands are not competing on a level field with highway intersections in Kent or airports in Everett. And they shouldn’t try. The city’s industrial lands have waterfront and a density of technical expertise that is simply unavailable to those other locations. Failing to recognize such strengths sets us up for a zero-sum fight with Edmonds that both cities and the region lose.

So when we take all these missing parts together and look at the focus areas identified in this Industrial and Maritime Strategy, we can see the absurdity of thinking so small. Fluffy clouds of buffers are some powerfully denialist thumb twiddling in the face of global financial mechanisms and catastrophic climate change.

The 12th Strategy: Inertia

Rallying a blue ribbon panel then punting to the next administration is where you see the soft power of a strong mayor. We know Mayor Durkan is ineffective at best and hostile to a livable, equitable city the rest of the time. Reports like this bear the inertia of her lame duck year. By simply letting the status quo roll forward, Durkan is leaving the city in worse shape because she is taking away time we could be using to do real equity work or prepare for climate change and its effects like we experienced this week. Thank god she’s not tear gassing neighborhoods anymore, Mayor Durkan is dawdling as the usual ones are set up to get more polluted for generations to come.

Here, possibly through the machinations of talented City staff, the strategy proposal does something right. The punt is not just a frilly list of things for the future administration and City Council to consider. OPCD is beginning an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) that will look at:

• High-density industrial development near transit;

• Housing and lodging in transitional zones;

• Legislation to close industrial zoning loopholes; and

• Formation of the stewardship group that will shepherd the recommendations.

Two things must come from this EIS. First, it must have a retrospective equity component. Too many times Seattle’s plans have talked about equity, reviewed their own process for inclusion, then carried forward a rehashed list of proposals from decades ago. Those old proposals never get vetted for how they impact marginalized communities. The Industrial and Maritime EIS must talk about how today’s existing policies come directly from old rules that created the segregation and inequality we live with now. The EIS must consider how to break that chain.

Second, the EIS must be robust enough that changes can be incorporated into the coming 2024 Comprehensive Plan. The Comp Plan will review the entire city’s land use policies in light of regional targets in Puget Sound Regional Council’s Vision 2050 plan and state growth management goals that include higher standards for housing, transportation, and environmental plans. Eyes are on land use in the coming administration, including among The Urbanist’s endorsed mayoral candidate Colleen Echohawk, and favorites for consideration Andrew Grant Houston and Lorena González.

Most importantly, we must recognize that a citywide industrial and maritime lands plan cannot be citywide in name only. If Seattle really has a commitment as a manufacturing and maritime city, that needs to mean the whole city. And it should. Businesses in our industrial lands pay taxes, provide jobs, and pump traffic and pollution throughout Seattle and the region. Narrowing the map and our brains to strictly consider industry as being within the industrial land boundaries only commits us to equally narrow thinking, and cuts us off from an environmentally just and economically robust future.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.