Through May and June, Seattle’s City Council will be considering a comprehensive rezoning of the city’s industrial lands. The changes are a long time coming, with many fits and starts. In following the evolution of this proposal, the legislation provides an interesting chance to say something I don’t often get to: the proposed new zones are good. In actuality, they’re so good that the city should go further.

The importance of getting industrial rezoning correct cannot be overstated. Seattle’s industrial areas comprise about 10% of the city’s zoned land and just as much of the city’s employment. These are the lands that made Seattle the epicenter of Cascadia’s jobs and connections to rest of the world.

The city’s industry is stuffed into two centers. Interbay is about 900 acres heavily dependent on maritime with Terminal 91 serving cruise ships at the south and Fisherman’s Terminal anchoring services for the North Pacific Fishing fleet around Ballard. The Duwamish industrial area is 4,200 acres centered on the Duwamish River and hosts the heavy Port of Seattle operations on Harbor Island, steel mills, shipping terminals, and Boeing in the south. There is a smattering of industrial around Lake Union, just to remind everyone that a Gas Works was there for a reason and the lake is really an airport.

Seattle’s industrial lands are threatened by climate change and decades of pollution. In both industrial centers, the land was claimed from marshes. Interbay was formed by lowering the level of Lake Washington with the Ballard Locks, the Duwamish by fortifying the banks of the Duwamish River, and Harbor Island by literally dumping a hillside into Elliott Bay. These areas will be the first reclaimed by rising sea levels, or inundated by a tsunami. All of the neighborhoods nearest industrial are subjected to noise and air pollution and the Duwamish is a heavily contaminated Superfund site.

Seattle’s industry is also threatened by years of mistreatment under current zoning. When the Growth Management Act was passed in 1990, it prompted the city and region to designate Interbay and the Duwamish as Manufacturing Industrial Centers. Those original plans haven’t changed, even though they include nothing about climate change, multiple stadiums, light rail, or even earthquakes. The documents which should have been replaced a decade ago now continue as zombie plans, still shambling around because they haven’t been superseded, but bearing no resemblance to anything alive today.

Such dead-hand control has lead to the city’s limited amount of industrial land being converted to non-industrial uses. Zoning, from its earliest incarnations in the Supreme Court case of Euclid v. Ambler Realty, has prioritized single family residences and dumped unwanted uses in industrial zones. Instead of seeing these areas as employment centers, they became catch-alls for open parking, big box stores, and mini-storage that didn’t fit anywhere else.

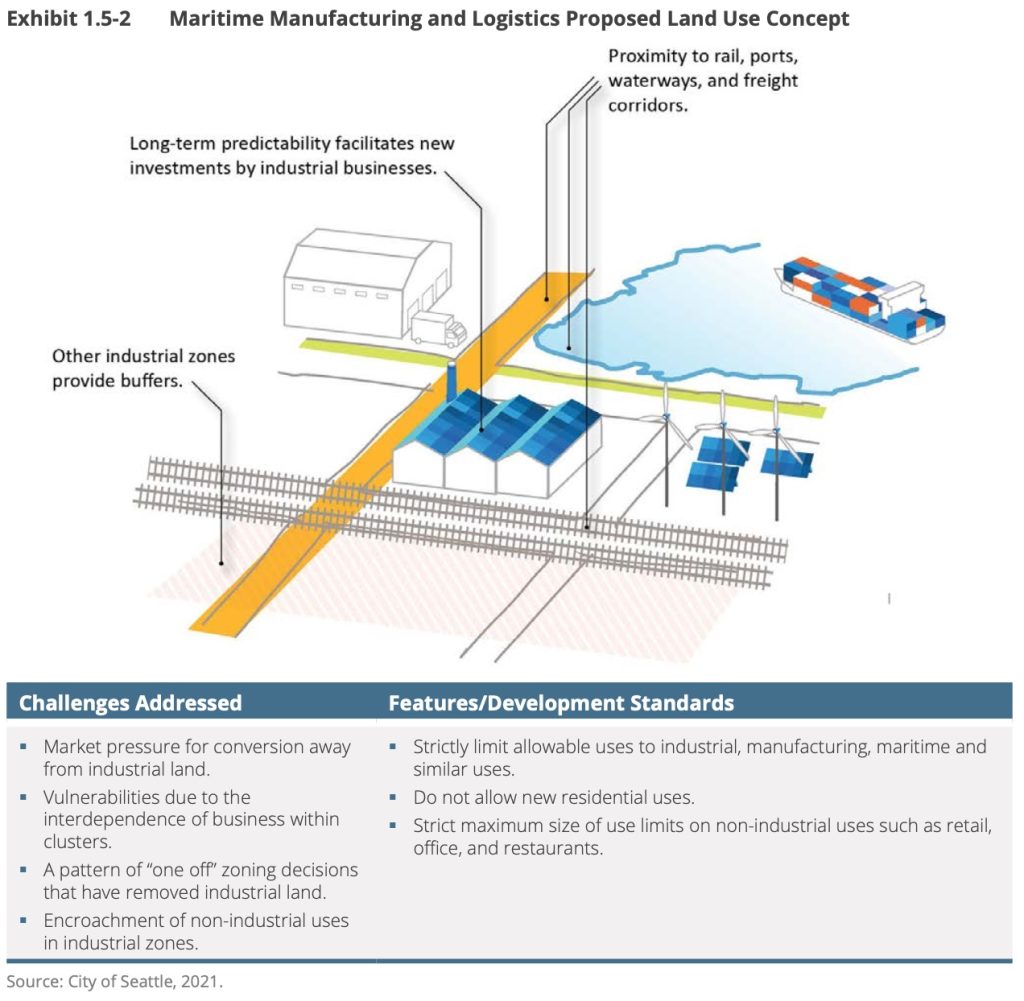

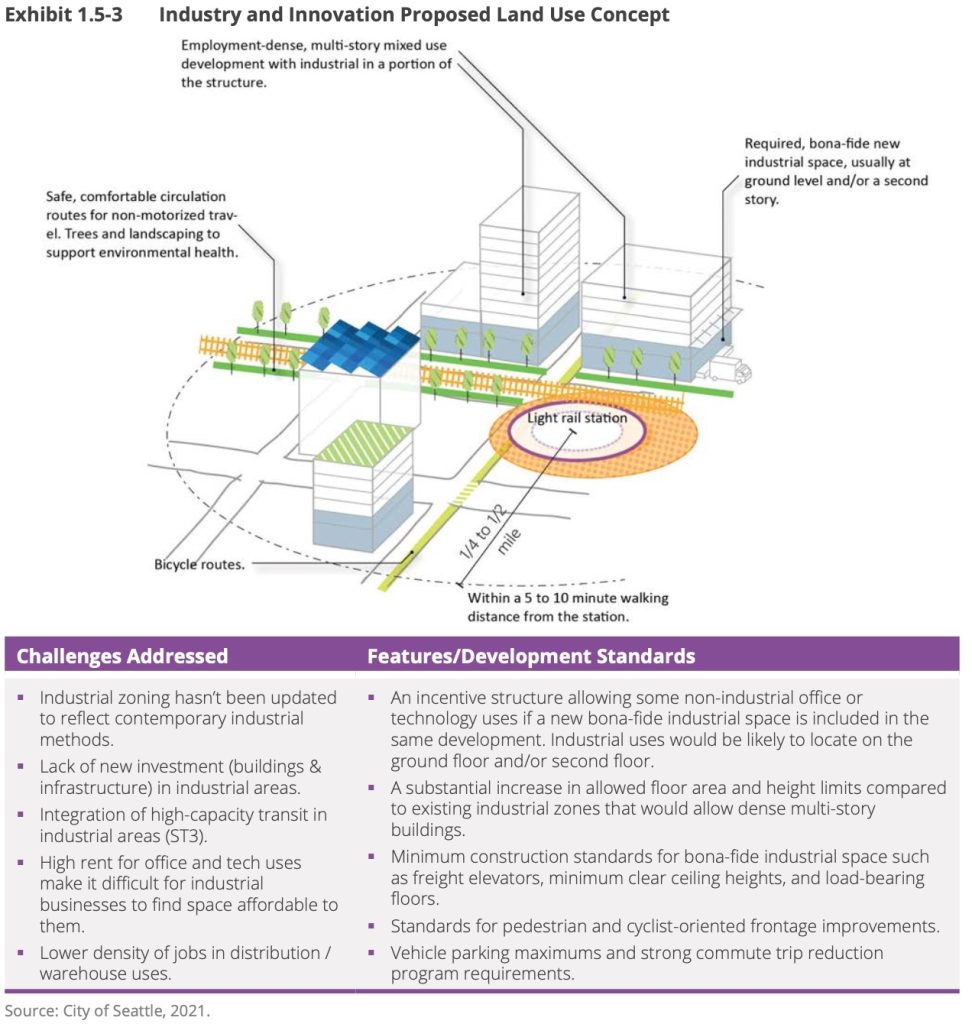

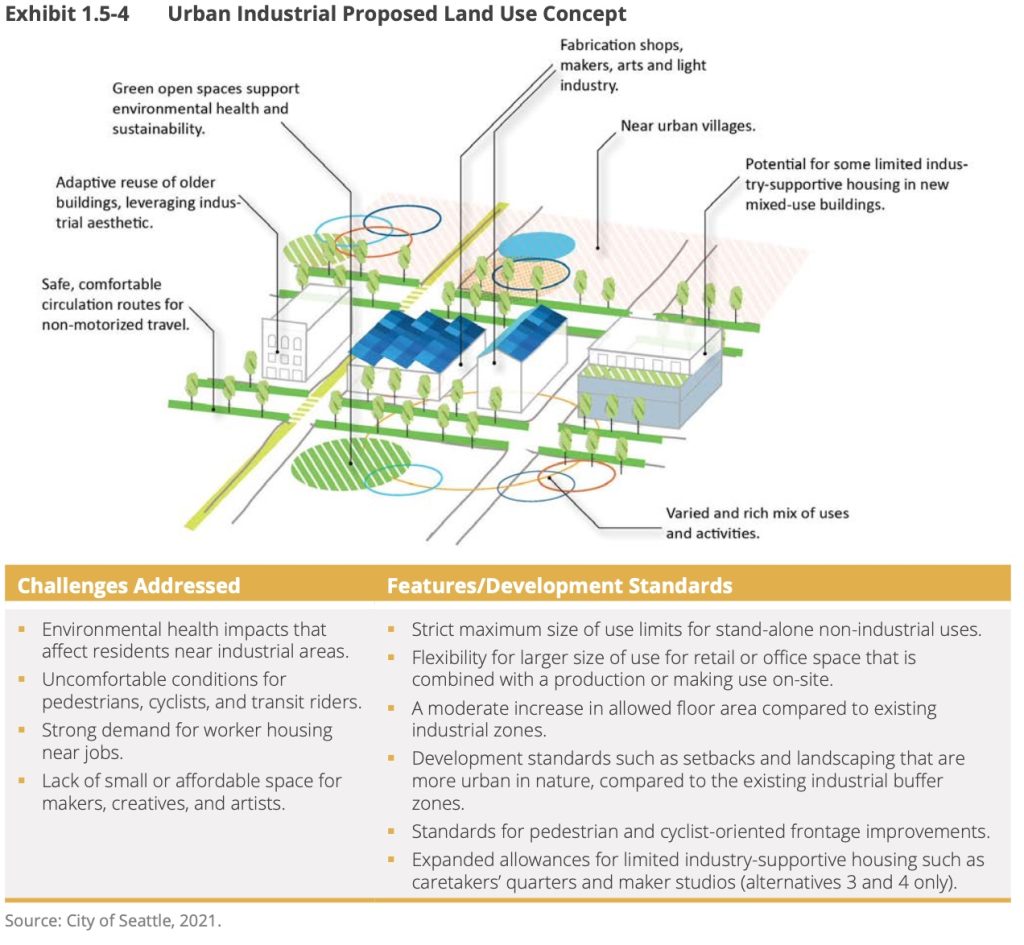

That is where Seattle’s new zones show promise. Replacing the antiquated perspective that industrial is just a synonym for anything goes, the city proposes three new zones. Mixed Manufacturing and Logistics (MML) is the basic industrial zone, focused on existing concentrations of core and legacy industries on flat areas around rail and ports. The Industry and Innovation zone (II) looks to transit-oriented areas of modern industrial buildings with high employment in emerging industries. And Urban Industrial (UI) has the goal of buffering core industrial areas from urban villages with affordable, small scale places for makers and brewers with supportive housing.

The goals are malleable, as many such planning documents tend to be. Where it matters is the text of the land use code, and that’s were the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) are doing things correctly. The proposed code allows for retail, but limits its size well below the 50,000 square feet of a big box store. And the new code outright excludes micro warehouses, which is the city’s definition of mini-storage.

And they’re actually replacing the old zones. As in, there is a specific bill to remove the hundreds of pages of old industrial text from the zoning ordinance. Absolute win.

The text of the new code also specifies which uses are considered industrial and which are not. That allows for the new rules to offer space bonuses to developments in the II zone that include industrial uses. So offices will be allowed in the II zones up to a 2.0 floor area ratio (FAR, a measure of allowable density). The FAR can double or more with the inclusion of light manufacturing, lab space, or other uses designated “industrial.” Mass timber construction can up this FAR further.

What’s also interesting is that the city appears to be pursuing the most permissive rezoning possible. Back when developing the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), the city based its alternatives on where the zones should be applied rather than the zones themselves. The four alternatives varied by how much the basic MML zone covered versus the more novel UI and II zones.

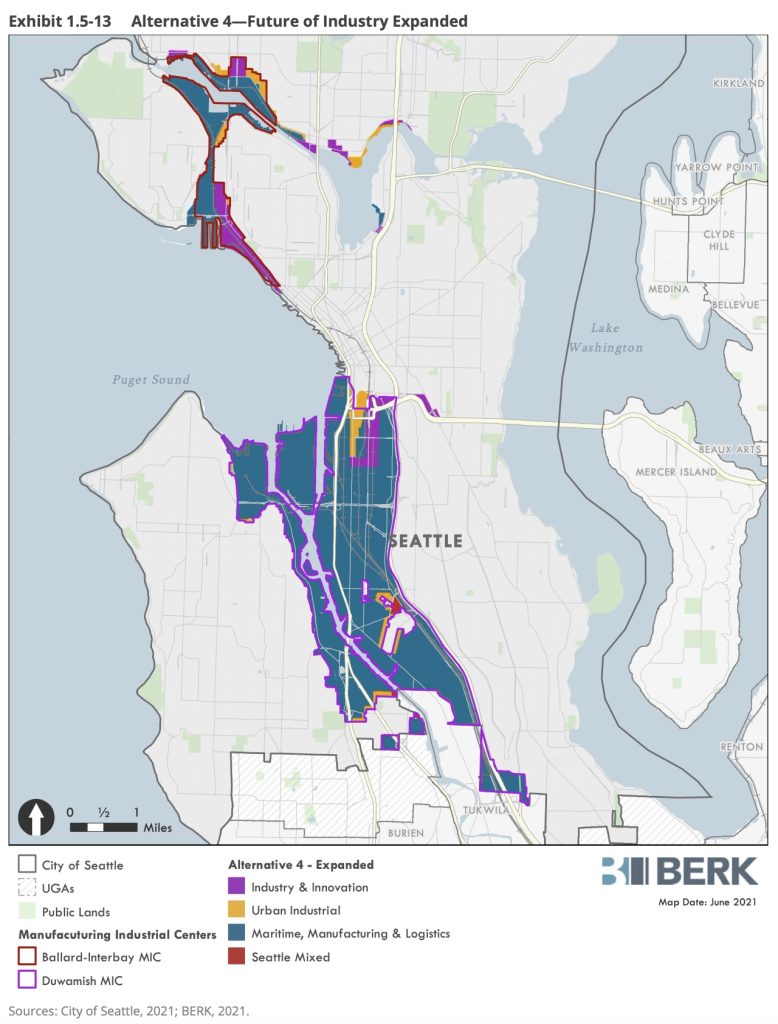

It appears that the council will be considering the “Alternative 4-Expanded” with some exceptions. This is the zoning map alternative that offered the most coverage by the new II and UI zones, predominately in the areas north of the Ship Canal and in the areas near the stadiums. Where the proposal departs from the posted alternative are also interesting. The Interbay Armory site will remain basic industrial (MML) as will the bulk of 4th Avenue near the ballpark. Georgetown will see an expansion in UI zones, and Judkins Park will completely go Neighborhood Commercial instead of II that was in the EIS. It’s a pretty aggressive rezoning, as these things go.

Alas, here is where we get into the places where the new zoning has some real issues. Basically, all of the problems stem from the fact that this is still very classical zoning living inside an enormous and complex existing zoning ordinance. It is exclusionary by nature, where any use not specifically permitted is prohibited. The new zones carry so much baggage that they should not have to.

While the zones are three fairly broad concepts, in application there is actually 11 different new zones. This happens because the city appends a height limit after each of them, so Urban Industrial becomes four zones called UI 30, UI 45, UI 65, and UI 85. There’s three more MMLs and four more IIs, with the legislation designating separate floor area ratios for each as well as other exceptions and special treatments. Just like the old zoning, a clear concept gets unbelievably muddled.

For example, the area just north of I-90 is proposed to be rezoned to the new II 85-240, a boost of height with lots of non-industrial uses allowed. While general II zones allow a mix of office, industrial, and hotels, the specification as II 85-240 opens an entire new section of the zoning. Entertainment uses up to 75,000 square feet are permitted, as is allowance for one additional FAR for automotive, retail sales, and other uses. Some street level uses are exempt from calculations. Above ground parking in this zone is exempt from FAR where the OPCD finds below grade is infeasible. All only within this specific 85-240 flavor of the II zone.

As the parcels north of I-90 on either side of Airport Way are the only places being rezoned with this super flexible II 85-240 designation, something doesn’t pass the sniff test. The site has been the focus of a lot of development concepts. First called S-Campus, it was to be a speculatively constructed mid-rise office park. Now, it is the center of the South-of-CID station concept floated by Mayor Bruce Harrell and King County Executive Dow Constantine to avoid a new light rail station in Chinatown.

Always, the zoning ordinance is an accretion of our hangups and fears. That’s why there’s still a page of requirements for “adult cabarets” in the new zones, in addition to the thousands of words the city code devotes elsewhere to defining adult uses in the most lascivious terms possible. Get over yourselves. Overregulation just extracts money for the few people who lucked into the land or licenses, and generally puts sex workers in precarious jobs if not outright danger. Since a number of the city’s strip clubs are in industrial areas, this would have been a good time to correct that noise.

Such historic lock-in appears over and over in the new code, even if it does not have to continue the old text. The II and MML zones specifically reference the city’s existing Manufacturing and Industrial Centers as criteria for locations. MML’s description actually starts with the phrase with “an existing industrial area” in defining the zone. The height limits that create all the sub-flavors of the new zones aren’t based on anticipated or acceptable height, but projections of what’s existing there. The only cluster of UI-30 is a half-block in Wallingford, and among the Expedia-to-Downtown strip of II-85, there’s a short block of II-125 across from Kinnear Park.

Much like the polluted industrial zones themselves, the proposed legislation doesn’t clean up enough of the messes left by the old zoning code. Seattle is in its predicament of diminishing industrial lands because the existing rules and zombie plans created a pressure cooker, limiting the spaces of the city that could allow big box stores, boat repair, airplane manufacturers, and coffee conglomerate headquarters. Legacy industries like fishing cannot compete with Starbucks and Whole Foods for land.

The new zones are good, but the legislation only ladles out a scoop of soup then turn the pressure cooker back on. Yes, big boxes and mini storage will have to find other places, but there’s now labs and offices with massive FAR boosts to start dealing with. Industrial zones need to expand to create employment centers in waining commercial areas and corridors outside of the existing centers. These new zones, particularly II and UI, are strong enough to run along Aurora, Lake City Way, and lots of places in North and West Seattle.

Unfortunately, the larger vision is not there. While the city is preparing an overall comprehensive plan rewrite, it was decided that this industrial area component would run ahead of the rest. The proposed legislation updates the city’s comprehensive plan just for industrial areas. Somewhat the opposite of a “One Seattle” plan.

Seattle is an industrious city, and the new industrial zoning is an opportunity to make sure that stays the case for the next century. It is a very good framework, but will require more effort and vision to make sure the new industrial zones stay relevant and do not fall into the same traps that made them necessary in the first place.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.