Whether pushing for a car-centric waterfront or failing to deliver on electric shore power, the Port of Seattle’s commitment to sustainability is an open question

It’s impossible to ignore a cruise ship docked on Seattle’s waterfront.

Recently, a behemoth Princess Cruise ship bound for Alaska – the Ruby Princess – towered over Terminal 66, reaching heights equivalent to a 15-story building. If the Columbia Tower, Seattle’s tallest building, was laid on its side, it wouldn’t measure up to the length of the Ruby Princess, which takes up 1,083 feet of the city’s seafront.

It is not just their size that is imposing. Cruise ship visits create both positive and negative impacts that can’t be ignored. On the plus side, the 289 sailings that 13 ships will make out of Seattle in the 2023 season between April and October are estimated to bring in $900 million worth of tourist revenue and support 5,500 local jobs.

Even though the Port of Seattle aspires to be the greenest cruise port in North America, these ships also bring a host of negative impacts to the city: pollution and carbon emissions, crowding at popular tourist sites, and pressure to build Seattle’s transportation infrastructure focused on automobiles and freight rather than transit and pedestrians.

In addition, the Port is behind schedule on promised plans to expand shore power, which allows these diesel-burning ships to turn off their engines while docked.

As I reported in a detailed multimedia feature published earlier this year at Hakai Magazine, Alaska cruises based in Seattle leave many harmful impacts in their wake. These include carbon emissions, sewage and scrubber discharge, noise impacts to Orca and gray whales, and overcrowding as the massive ships disgorge thousands of tourists into tiny Alaskan towns.

Seattle isn’t tiny, but it too feels the impact of this industry.

The Wide Stroad to Alaska

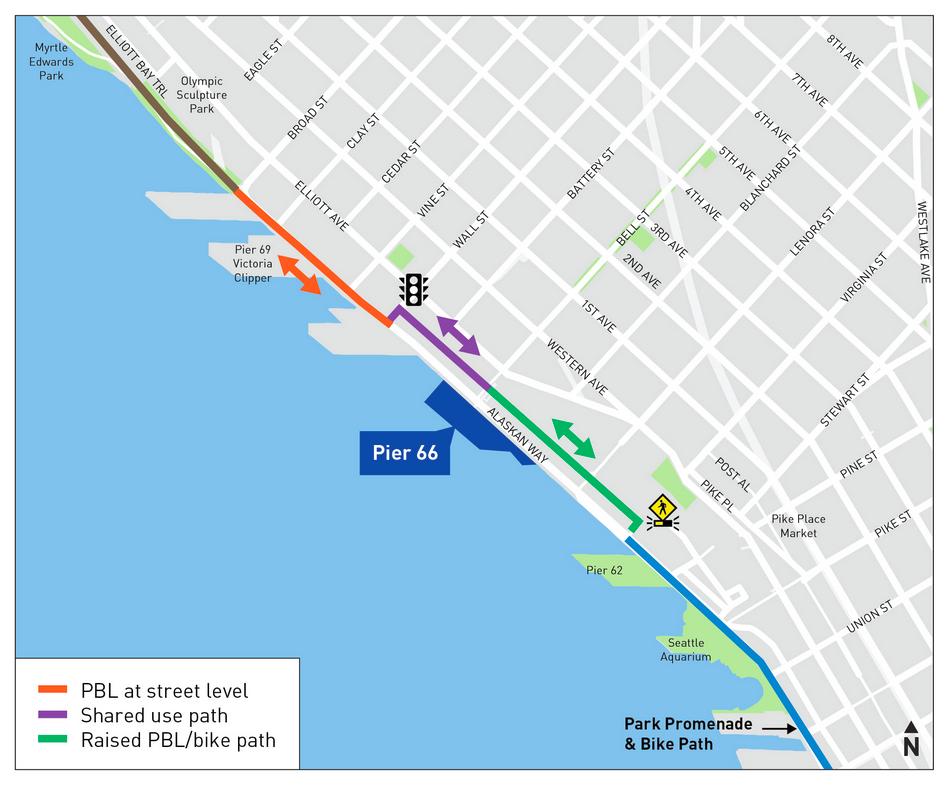

As new wide arterials recently opened at Alaskan Way and the new “not a highway” known as Elliott Way, the Port of Seattle and the cruise industry it supports have contributed to Seattle falling behind on its sustainability goals.

Gordon Padelford, of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, is disappointed that the Port of Seattle has been reluctant to support a continuous, protected bicycle and pedestrian path alongside the newly reconstructed Alaskan Way. “If the Port really wants to demonstrate its sustainability bonafides, it needs to fully support a continuous waterfront trail for Seattle,” noting that a completed waterfront trail connecting to the Elliott Bay Trail would rival the Burke-Gilman Trail as the city’s most popular trail.

In an interview with The Urbanist, Stephanie Jones Stebbins, the Port’s managing director of maritime, said, “We are actually very supportive of a separated bike pathway as long as that can be dual use for operations when it’s not being used as a bike path.”

“When there’s a cruise ship in town, it does not make sense to have a bike lane in front of the cruise terminal. It makes sense to have a bike lane on the side of the road where there’s already a bike path right now.”

That “bike path” is currently a raised sidewalk. Padelford says making cyclists and pedestrians cross busy Alaskan Way twice, which is still SDOT’s preferred solution, isn’t tenable.

“Requiring people to go across the street on the east side sidewalk and then go back across the street again – which was the original proposal – is a non-starter,” he said. Padelford is optimistic, however, that a compromise solution involving flaggers temporarily directing bike traffic away from the cruise terminal during busy boarding hours can solve the problem.

Angela Brady, director of the City of Seattle’s Office of the Waterfront, defends the newly opened four-lane roads and says the second phase of the project will include much more landscaping and will be more pedestrian-friendly than it currently is. “This really allows us now to focus on construction of the new park, which is the long linear park on the water’s edge that will be more focused on pedestrians and bicycles,” she said.

Responding to viral online criticism of the newly opened project, Brady said, “The viaduct carried 110,000 vehicles a day. We’re now only carrying about 18,000. So, that’s a significant reduction in the volume of vehicles as compared to the Alaskan Way Viaduct. And you know, our speed limits are 25 miles an hour and not 50. It’s not a freeway.”

Brady acknowledged that the Port, along with the Washington Department of Transportation, were among the project stakeholders urging that Alaskan Way should move a significant number of vehicles. “Yes, the Port has been vocal in the support of the maritime industry and the cruise ship industry and the efficient transport of goods and services via freight,” she said.

In its 2016 Environmental Impact Statement on the rebuild of Alaskan Way, the Seattle Office of the Waterfront pointed to the Coleman Dock ferry terminal, freight traffic, and the needs of cruise ships at Terminal 66 as impetus for a multi-lane roadway. “As a result of these factors, traffic on Alaskan Way at Yesler Way is expected to increase substantially between 2010 and 2030,” the report concluded.

Seattle’s Climate Action Plan, first released in 2013 and updated in 2018, calls for the city to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 58% below 2008 levels by 2030 and reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Stumbles on the Path to Shore Power

One of the Port’s big talking points is its distinction of being one of the first ports in North America to introduce shore power, which allows ships to shut off their engines and plug into electric power while loading and unloading passengers, food, and supplies during the nine to 12 hours these huge boats spend in Seattle.

Unfortunately, the Port’s efforts to stop cruise ship emissions while they sit in Elliott Bay have fallen well short of their goals. Only Terminal 91 in Interbay currently offers the option of shore power. At Terminal 66, which is not equipped with shore power, a plan to have electricity available at the start of this season was scuttled, and has been delayed to midway or late in the 2024 season. The issue, Jones Stebbins said, is power cannot arrive through downtown.

“Where it’s located, we would have had to dig up an incredible amount of downtown streets to get power there,” she said. Instead, rather than disrupting all those cars, the Port’s engineers have been working on designing and installing a giant underwater cable to electrify Terminal 66. “We’re working on getting a mile-long underwater cable – but supply chain issues have come into effect,” she said, noting construction could continue well into 2024.

Last year, of the 295 cruise ship sailings that left Seattle, 141 were equipped to plug in to shore power. But only 69 of those ships actually plugged in and turned off their engines.

Via email, Jones Stebbins said the reasons that fewer than half the ships that have capability actually plugged in were:

- “The ship attempted to connect several times and was unable to establish a connection due to a ship-side issue.”

- “The ship did not connect due to [an] issue with the shore power connection system.”

- “The electrical department that establishes the connection was in isolation due to COVID.”

- “There were several attempts to connect but the connection failed due to synchronization issues.”

In her interview with The Urbanist, Jones Stebbins said the main issue at Terminal 91 was similar to when someone pulls their car into a gas station and finds that their gas tank is on the side opposite the pump. “We’re seeing that the location on the vessel doesn’t necessarily line up with where our shore power is,” Stebbins said.

In order to fix this rather unfortunate oversight, Jones Stebbins said work is currently underway, funded by the Port’s capital plan, and will continue into the 2024 season. Jones Stebbins said the Port hopes that this year, even with all the glitches, 38% of ships (111 sailings) will successfully utilize shore power.

On top of that, Jones Stebbins said cruise lines are introducing new ships that aren’t compatible with current facilities at Terminal 91. “There are some new vessels coming that will not fit with our systems,” she said. “So we’ll be upgrading.” She hopes this work will also be finished by 2024.

The Port’s stated goal is to require all ships to plug in by 2030.

The Port estimates its shore power program reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 2,000 metric tons last year.

According to estimates I calculated in my feature for Hakai magazine, just one average-size cruise ship carrying 3,600 passengers generates 2,800 metric tons of CO2 during a single, seven-day sailing to Alaska and back.

“I mean, sure, shore power is great,” said Anne Marie Dooley, a physician and kidney specialist with Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility, an organization that’s critical of Seattle’s cruise industry and the fine particulate pollution its ships produce. “But that’s like saying I drive my hybrid all week using gasoline and then I plug it in when I come home on the weekend.”

A 2021 paper published by a team of UW researchers found that in a long-term study of residents of the Puget Sound region increased exposure to fine particulate pollution of PM 2.5 or smaller – which is often produced by diesel engines – resulted in an increased risk of dementia.

“The Port is consistently talking about jobs and money going into the local economy, but they have to be honest about the costs,” Dooley said. “They tend to externalize the health costs on to the public from polluted air. There are 50,000 deaths a year in the United States from polluted air. The Port is a big contributor. It’s not just the cruise ships, it’s the entire amount of traffic that they generate: planes coming in, the tour buses.”

The Port’s Qualified Support for Transit

Despite a light rail system from the airport to downtown and beyond, Jones Stebbins said the majority of cruise passengers arrive at their ship via tour buses – even though Terminal 66 is relatively close to downtown. “The cruise lines hire tour buses,” Jones Stebbins said, “but we certainly have Ubers, Lyfts, and taxis as well.”

An ecologically-minded cruise tourist interested in taking transit from SeaTac International Airport to their ship at Terminal 91 needs to allow for an hour and 13 minutes of travel time using a combination of Link light rail and Metro’s route 24 bus to Magnolia.

“It is difficult to get there on transit,” Jones Stebbins admitted. “Although I always see people with their suitcases walking through Centennial Park and Myrtle Edwards Park – people do it.”

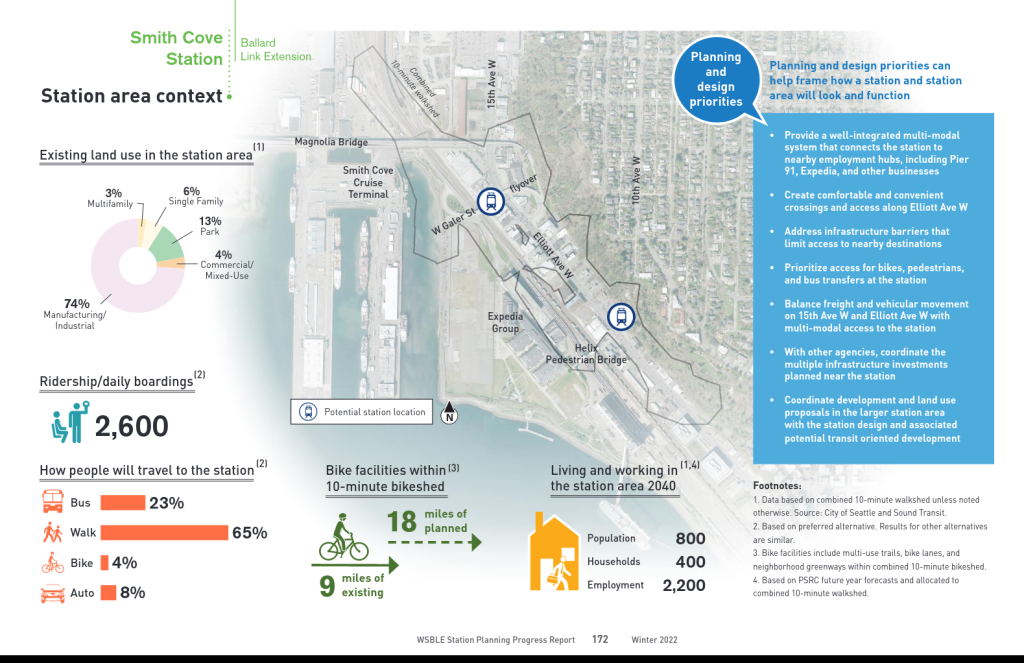

The cruise terminal at Pier 91 is poised to benefit from the planned Ballard Link light rail extension, with a proposed Smith Cove station potentially situated within reasonable walking distance to the cruise ships docked there.

In comments submitted last April for Sound Transit’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) on the proposed Smith Cove station, the Port wrote in support of easy access for passengers and employees: “Please work with us to consider how the Smith Cove station could better serve the fishing and industry employees at [Terminal] 91 and especially the hundreds of thousands of cruise passengers and employees at Smith Cove Cruise Terminal. This could also include an opportunity for a Transportation Hub in the Smith Cove area which could provide opportunities to connect passengers from Sounder train service and Link Light Rail.”

However, the Port in the same letter expressed concerns about freight mobility to Ballard and construction impacts to its cruise terminal in Interbay: “The Port of Seattle is also concerned about the Ballard Link Extension and potential impacts to Terminal 91 (T91) and Fishermen’s Terminal and/or access to these sites, along freight arterials and from the ship canal for marine vessel access. Even closures less than the one‐year threshold in the DEIS, which could impact a season of fishing or cruise activity, put at risk a whole year’s value.”

Tija Petrovich, with the Pioneer Square Residents Association, and a frequent critic of the Port of Seattle, thinks the Port could learn from Lumen Field and Climate Pledge Arena, both of which work hard to encourage their customers to use transit.

“We’re constantly working to have less cars in our area,” Petrovich said. “I would love it if the Port talked with the stadiums and asked them: how do you reach your people? How do you take surveys? How do you encourage them? Because [the stadiums] have some fantastic statistics on dropping the amount of cars that actually hit the streets for big events here.”

Mitigating Tourism Impacts

Petrovich, who’s lived in Pioneer Square for 30 years, is concerned not only with cruise ship emissions and the ships’ effects on marine ecosystems, but how the huge influx of tourists affects the character of local businesses.

“We’ve had a lot of businesses displaced,” she said. “I worry about what’s going to come in. Is it just gonna be another t-shirt shop? Pioneer Square is a very special area. . . and I don’t want to become a tourist trap, like elsewhere.”

Unlike tiny towns in Alaska like Skagway or Ketchikan, cruise ships don’t double the population of Seattle. Jones Stebbins notes that one cruise ship with 5,000 passengers has much less impact than a single Mariners game.

Still, the crowds in Pike Place market each summer are substantial – and cruises certainly feed them. When asked if he thought the Port should support making the Pike Place, which runs through the market, pedestrian-only, Padelford said, “Places folks love to take cruises to in Europe are really pedestrian-oriented or pedestrian-only in some instances. So I think the Port could play a role in saying this is the kind of downtown streetscape that we want to see and it would really support in revitalizing downtown. I think it’s an intriguing idea.”

A spokesperson for the Port said it had no plans to take a position on whether the city should limit cars on Pike Place.

For all its stated commitment to sustainability, the Port is still firmly committed to fossil-fuel powered transportation. Meeting its goal of zero emissions by 2050 is going to be difficult, and Jones Stebbins admitted that getting the cruise industry to transition to zero emissions by then (she firmly says that liquefied natural gas powered ships will not meet that goal) will be a “hard nut to crack.”

For his part, Padelford wishes the Port would do more to prove its commitment to sustainability through its actions as well as its words.

“I think there’s an opportunity for freight advocates to join up with safety and sustainability advocates,” he said, “and say: We can build freight lanes; we can build bus lanes to keep freight and transit moving – while not providing an excuse to maintain these giant roads that we know are killing people and we know are damaging our health and environment.”

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.