Restrictive zoning has created urban forms that are expensive, exclusionary, and unsafe, but Home in Tacoma reforms could address that.

Discourse around Home in Tacoma from 2020 through 2023 has focused on housing, and for good reason: through Home in Tacoma, the city aims to remove barriers that have resulted in an urban landscape characterized by “missing middle housing.”

“Missing middle housing” is a term used by urban planners and designers to describe the types of housing types that used to be common in the U.S. — multifamily and clustered — and which remains common in other parts of the world. The U.S. and Canada are outliers to the extent they have sought to enshrine and protect the single-family detached home through zoning regulations.

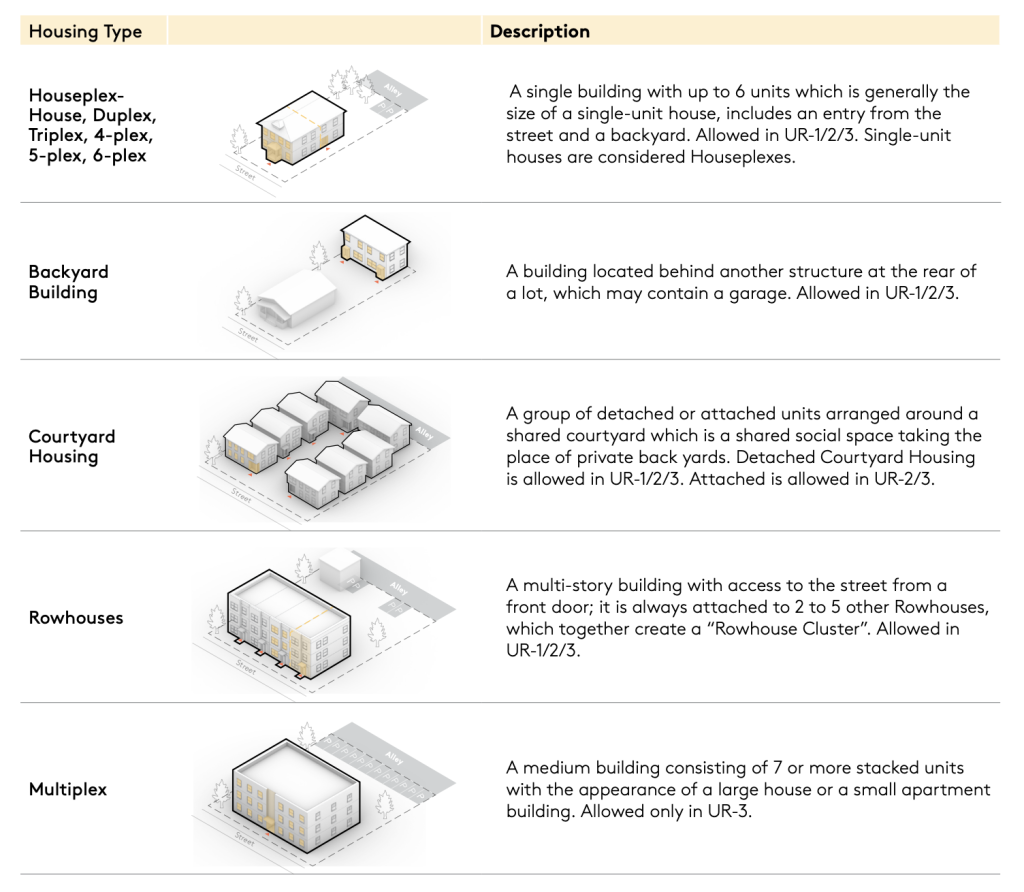

To visit other parts of the world and to envy the walkable neighborhoods that serve as a transition between the collection of single-family homes and the denser, busier parts of the city is to envy the type of urban environments missing-middle housing could provide. Duplexes, courtyard apartments, and rowhouses are examples of “missing middle housing,” as we used to build a lot more of these in the U.S. prior to the midcentury.

Walking around Tacoma, you may still spot a few of these housing types. These remnants remind us of the varieties of housing one could aspire to in cities before the effects of zoning took hold.

New York City adopted the first city-wide set of zoning regulations in 1916, breaking up the city through these according to allowable densities, building heights, and area uses. Early zoning codes were sold to city dwellers as a measure against having residences next to polluting industry. But zoning codes were also used to –and quickly became the tool of choice for — keeping certain “undesirable” residents from certain parts of the city.

By the end of 1916 seven other cities joined New York in adopting such regulations. Ten years later, in 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the constitutionality of zoning codes via Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co. Reading the Court’s arguments in this case is revealing: “With particular reference to apartment houses,” wrote Justice George Sutherland, these are “a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surrounding created by the residential character of the district.”

In effect, Sutherland’s and the Court’s defense of zoning codes was effectively a defense of single-family detached homes, a designation to be protected at all costs against apartments and “their necessary accompaniments,” which Sutherland listed as “disturbing noises, increased traffic,” and “the occupation of larger portions of streets,” by cars. Density and its “accompaniments” were bound to “deprive children of the privilege and quiet of open spaces…until, finally, the residential character of the neighborhood is destroyed.”

In ten-year’s time — by 1936 — more than 1,322 municipalities had adopted such ordinances. And the attitudes against apartment homes and other types of multi-family housing — and those who live in them — became just as widespread.

If the original and early zoning codes were rather liberal and permissive, it was largely in recognition of — and in deference to — the legal doctrine underpinning them: under police power rights, local and state governments can exercise power over private property in the interest of “health, safety, morals, and general welfare.” But the application of zoning codes towards the prohibition of density in an effort to maintain the subjective “character” of a single-family residential area have become very restrictive. And in their application we find the daily facets of our lives controlled.

Modern zoning codes, for example, often dictate a minimum square footage for a house and a minimum number of parking spaces. They might dictate what one can build on a lot, or what types of activities one may legally take up there. A lot of what modern zoning codes dictate cannot be directly tied to the promotion of “health, safety, or general welfare.” These dictates can be tied to the protection of single-family zoning, however.

Zoning codes give shape to our neighborhoods and to our daily life movements. The cost of housing, be you a renter or an owner, is largely informed by zoning (consider parking minimums: a developer must build a certain number of parking spaces, and that cost gets built into the cost one pays for rents or into the mortgage, whether you drive a car or not). Having a grocery store near home — one you walk to or one you have to drive to (and hunt for a parking space at), that is a matter of zoning. Living in a neighborhood that is mostly composed of people who resemble you in terms of age, race, and socio-economic status — that is also a product of zoning.

Zoning is the policy gift that keeps on taking.

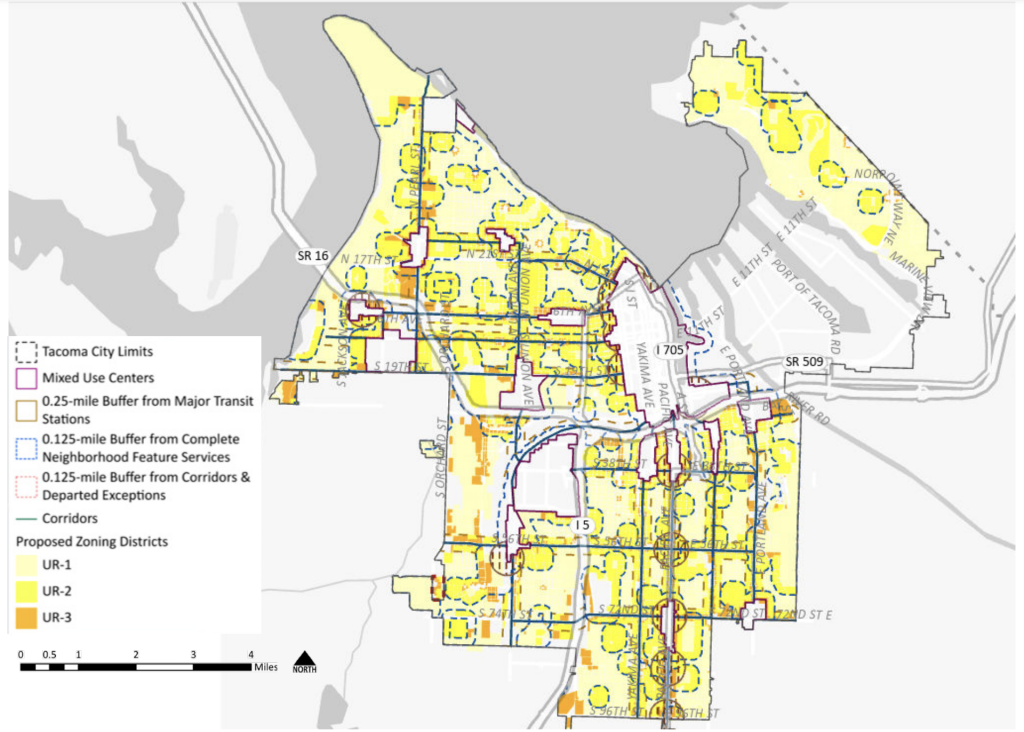

What the draft package the City has delivered shows is that to create more areas of Tacoma that resemble the Stadium and Proctor districts — parts of the city that people like — active and complete neighborhoods that are often mentioned as the “nice parts of Tacoma,” it takes more than building more “missing middle housing.” That Tacoma is leveraging zoning reform through Home in Tacoma as an opportunity to also revise a bevy of other impediments to the quality of life that only urban forms can deliver makes sense for a city that intends to grow not only in numbers, but in livability.

While the draft package does still emphasize “Housing Types” in the plan, we also get a greater sense of how Home in Tacoma is meant to be a comprehensive undoing of all the secondary and tertiary effects of cities made through zoning.

The draft package includes details on how Home in Tacoma will implement “changes to parking requirements,” which not only involves creating “Reduced Parking Areas” that promote greater walkability and cycling, but which also offer bike parking. To address the many ways parking has undone our access and quality of life is to work towards more complete neighborhoods — the type of neighborhoods where we can all access what we need and want safely and conveniently.

Also included in the draft package is information on how zoning reform coincides and aligns with our environmental, sustainability, and climate-related goals and plans. Not only does the package show how this growth, densification, and remaking of our city will impact our natural environment, it also centers the many and diverse natural resources in our city. Trees, for example, are referenced specifically, and in conjunction with our newly adopted tree ordinance, we can look towards growth and density that does not operate under a false dichotomy: trees vs. density.

M. Nolan Gray, research director of California YIMBY, reminds us that “zoning is not a good institution gone bad.” Rather, zoning should be thought of for what it is — for what it has wrought: “…a mechanism for exclusion designed to inflate property values, slow the pace of new development; segregate cities by race and class, and enshrine the detached single-family house as the urban ideal.” We see how zoning has done all of these things to Tacoma. So do many other cities in our region and nation; so does the State of Washington.

Home in Tacoma is not without its detractors. There are those who have long benefited from the conditions created through restrictive zoning. But the quality of life we see and envy in other parts of the world should not be only available to those who can afford to live in singular parts of our city, or to those who can afford to visit, for short periods of time, cities where zoning has not been allowed to reshape the city for cars and capital.

For all it does offer, this draft package does leave two fairly major questions unanswered: how are we going to actually move people about the city if not cars, and how are we going to pay for the improvements and additions to the infrastructure that more housing and more people will require? These are complicated questions, and no single solution exists. But the plan could use with more details or specific options that are under consideration.

Developer impact fees are one way that other cities are deploying to help mitigate the high costs of improving or building new infrastructure. While impact fees can be a deterrent to more building housing, reasonable impact fees can be a meaningful way to create more complete neighborhoods as we add more housing.

Tacoma officials should outline how our public transportation agency partners will deliver the levels and quality of service a city that is dense and active requires. Already, these agencies are struggling to serve Tacoma residents at the levels we require. While Pierce Transit and Sound Transit have indicated that they are both exploring options to increase operations (which, on some routes, is already needed), it still is not clear how either agency will fill its operator shortages, or how they are to build higher-capacity transit at lower costs and with fewer delays.

The question of how we are going to get people out of their cars is an important one to answer now, lest we end up with greater levels of car-related congestion and higher levels of road violence and death. The way Tacoma is designed still tells people that the best way to move through and arrive at desired places is via car. A few, scarce places in our city say otherwise, but we still encourage driving by limiting transit options and by allocating more space to cars rather than people even in these neighborhoods.

Mobility is a question of transit, sure, but it is also a question of creating the types of streetscapes that people feel and know are safe to be in. We need wider sidewalks, abundant street furniture and street trees, a greater variety of storefronts, better street lighting, and a network of pedestrianized streets and corridors where cars are not the default — but where people are.

These uncertainties aside, this draft package is a preview of the type of city Tacoma could be. Another revision should certainly work towards more specificity. We have a chance at transformative change in Tacoma through Home in Tacoma. A chance to create the type of city where people come and say, “Wouldn’t it be nice if we had this, too?”

Rubén Casas

Rubén joined The Urbanist's board in 2022. He is a scholar and teacher of rhetoric and writing at the University of Washington Tacoma. He is also the faculty lead of the Urban Environmental Justice Initiative at Urban@UW. In his work and advocacy, Rubén examines how cities and the institutions that comprise them imagine, plan, and build in ways that promote and/or discourage community and a sense of place.