You might be surprised to learn it is illegal for a city in Washington State to set a speed limit lower than 20 miles per hour, but it’s true. The top speed of many e-bikes is essentially the minimum speed limit for cars on any public street. However, starting on July 27th, that will change. Under Senate Bill 5595, signed on Saturday by Governor Bob Ferguson, Washington cities will have the legal authority to create a new type of street that features much lower speed limits and puts pedestrians first.

What is a shared street?

A shared street, as defined by SB 5595, has a speed limit of 10 miles per hour and allows pedestrians to walk in the center of the street. Jaywalking laws — an early project of the auto industry — no longer apply. Cars are allowed but pedestrians have the right of way.

Rather than requiring pedestrians to conform to a highly ritualized process of walking along and crossing the street at specified times and locations so as to privilege cars, SB 5595 exempts pedestrians from this process and gives them true priority. The law establishes a clear hierarchy where bicycles must yield to pedestrians, and cars must yield to bicycles.

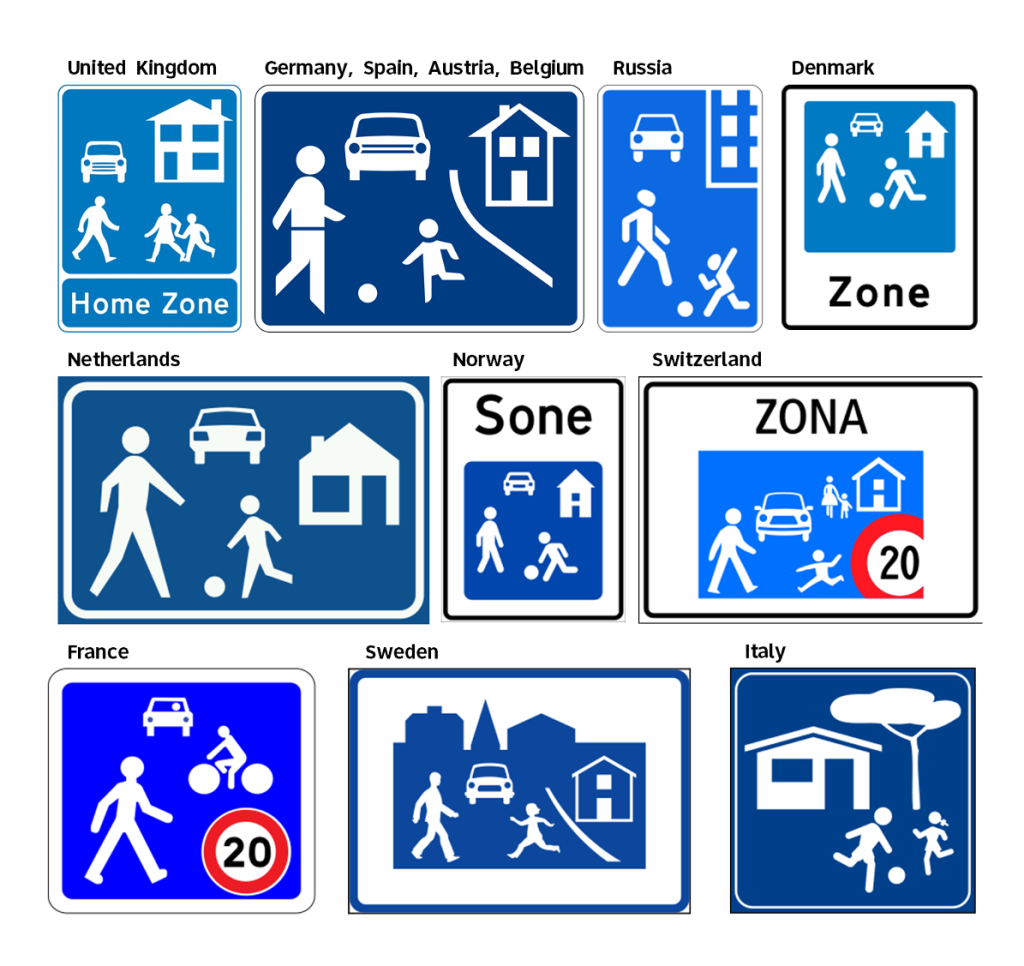

Shared streets may be new in the United States but they are common across Europe, where they go by various names such as “woonerf” or “home zone.”

A classic European shared street or “woonerf” is narrow and curbless with a clear zone suggested by paving materials and personal items like tables, chairs, and planters along the edges. It may also include bollards and other hardscape materials that protect personal items and provide refuge for pedestrians when the occasional car needs to inch past. The physical attributes of a shared street can vary.

Don’t we already have shared streets? What about Pike Place?

If you think woonerfs (or, as they are pluralized in Dutch, “woonerven”) already exist in the United States, well, there is no law against using the term whether it is accurate or not, and American architects love to call things woonerfs, even when they are just curbless streets or worse yet… parking lots.

The things we call woonerfs in America tend to be far more car-oriented than streets where the European legal definition applies, and it has become all the rage to affix that label to any curbless street, even ones that are vastly wide with multiple lanes of traffic, or where the primary function is vehicular throughput or access to parking.

Pike Place, which is currently governed by a City of Seattle ordinance that conflicts with state law, is the closest thing we have to a shared street here. The ordinance states:

No pedestrian shall cross an arterial street other than in a crosswalk, except upon the following portions of streets within the Pike Place Market Historical District:

(1) Pike Street, Pine Street, Stewart Street and Virginia Street, west of First Avenue;

(2) Pike Place between Pike Street and Virginia Street.

Pedestrians have the right of way and may walk in the center of Pike Place but the speed limit, you may be surprised to hear, is still 20 miles per hour. Fortunately, the design and operation of the Pike Place — with textured paving, clutter at the edges, a high volume of foot traffic, a location on the fringe of the downtown street grid, and (until recently) a continuous traffic jam — keeps speeds low, and the actual speed limit isn’t posted.

Unless it is fully pedestrianized (and not shared with cars), Pike Place is an obvious street upon which to confer shared street status. Let’s hope it gets permanently pedestrianized first.

Lord, I have seen what you have done for others…

According to Wikipedia, which has a fairly thorough but certainly not definitive article on the topic, no state in the US allows a speed limit as low as 10 mph. None, whatsoever. SB 5595 is a groundbreaking new law that other states can replicate.

Shared streets have the potential to dramatically change the way we move around cities in the state of Washington. If you have been to any European or Asian city where shared streets are common, you have experienced the difference. Residents use shared streets as an extension of their homes, cafes spill into the street, and children move about freely.

If the tech industry gets its way, our cities may soon be radically reshaped by autonomous cars. But we are much better off as a society if we create cities safe enough for autonomous kids. When we give kids greater autonomy, we improve the lives of caregivers, as well, and we improve civic life overall.

A system of streets with pedestrian priority and much lower speed limits can enable 15-minute neighborhoods, where residents are able to serve their daily needs within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. It can provide greater dignity for people moving around neighborhoods that lack sidewalks. It can transform school drop-off lines to a pleasant walk. It can provide a safer space for people with mobility challenges. It can reduce the sense of isolation elderly residents experience when they lose the ability to drive. It levels the playing field and addresses the imbalance between cars and everyone else.

Are American streets too wide to be shared?

Shared streets are compatible with a range of urban environments. Rue de la République in Lyon, France, shown below, is considerably wider than the Dutch woonerfs above. This street could be successful if it were fully pedestrianized but the local authorities have decided to maintain vehicular access. The granite obstacles and active pedestrian land uses along the edges encourage very slow speeds. In addition, mapping apps have been advised to route vehicular traffic around it.

Oudburg, that shared street in Ghent, Belgium, is divided roughly into thirds, with fixed structures like tables, chairs, and bike racks on either side and a clear space in the center—indicated by distinct paving—shared by pedestrians, bicycles, and cars.

Oudburg was fairly pedestrian-oriented by American standards before it was rebuilt to provide more space for non-motorized uses. This physical transformation you see above occurred in conjunction with a traffic circulation plan that eliminated vehicular through-traffic in the center of Ghent.

A successful shared street has three basic characteristics. The first two are about governance: 1) a low legal speed limit and 2) a legal right for pedestrians to occupy the entire street. Both are provided by SB 5595. The third characteristic is 3) a physical design compatible with the other two.

So, that can mean eliminating curbs but it also requires features to reduce traffic volumes, slow speeds, and provide refuge for pedestrians. The Seven Dials district in London provides an excellent example. The shared portion of the roadway is narrow. Pedestrians can cross the roadway wherever they like and can walk down the center, but there are significant areas, protected by well-spaced bollards, where pedestrians can find refuge. Trees are a bonus.

Rue Cadet in Paris, below, is a variation on the Seven Dials example. In terms of regulation, this street is pedestrian-only but allows service vehicles with no time limitations and the speed limit is set at 18.6 miles per hour (30 kilometers per hour), although actual speeds are considerably lower. This design would be suitable for a shared street. There is a well-defined but narrow shared roadway in the center, a pedestrian comfort zone protected by bollards on the left, and built-up dining areas on the right.

Note the Paris example above doesn’t provide much protection from cars on the right side. This seems to work fine in Paris but American landscape architects should be wary. Our vehicles are larger and our car culture is… well, they don’t call this ‘Murica for nuthin’ — so a simple copy-paste is not always advisable. This will be especially important for the early implementations of shared streets, when users are getting acclimated to the concept.

The Shared Streets Law enables Washington cities to move more easily to a future where cars are completely eliminated on certain streets. Note the car parking sign behind the bike parking sign on the Barcelona example below. While cars are allowed on this street, the superblock circulation plan makes it less useful as a through-route for cars. With well-designed shared streets, you don’t have to wait for property owners to decommission their driveways to create high-quality pedestrian-centered public spaces.

The Shared Streets Law has the greatest potential in residential settings, especially in places that lack sidewalks. Antwerp, Belgium is building entire networks of garden streets, one of which is shown below. These are streets governed by Belgium’s woonerf law where the focus is improving safety while adding greenery and removing impervious surfaces.

The design of American streets vary but, with some creativity, we have the potential to retrofit them using the new flexibility provided by the Shared Streets Law.

The (relatively) short and winding road

Remarkably, the Shared Streets Law passed the Washington State Legislature on the first try, and made it through the legislative process virtually unchanged from the original that I proposed to Representative Julia Reed’s office in October 2024. This law only exists because of the diligent and responsive constituent service of Rep. Julia Reed of Washington’s 36th District. Her office engages with local safe streets advocates on a regular basis.

Senator Emily Alvarado of Washington’s 34th District was the prime sponsor of the lead bill in the Senate and together they attracted seven co-sponsors each in the House and Senate. It is notable that SB 5595 was Alvarado’s first bill to pass out of the Senate after becoming a member of that body.

Every year since 2018, the City of Seattle’s legislative agenda included a desire for greater regulatory flexibility to set lower speed limits but they never proposed a bill. However, once a draft of this bill began to circulate, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) was enthusiastic. SDOT City Traffic Engineer Venu Nemani testified in favor and Mayor Bruce Harrell lobbied behind the scenes to get Republican support. The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) supported the bill and numerous advocacy organizations, like Transportation Choices Coalition and Seattle Neighborhood Greenways did, as well.

My original name for the bill was the Woonerf Ban Repeal Bill. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed, and the folks who guided the bill through the legislature emphasized its importance as a way to create more vibrant streets around the 2026 World Cup.

While the shared streets bill was bipartisan, it lost most (but not all) of its Republican support when Representative Joe Timmons (D-42nd, Bellingham) added an amendment to allow shared streets on certain state highways that serve as “the primary roads through a central business district.”

Belgian roots

The Shared Streets Law is based on Article 22 of the Belgian traffic regulation that defines woonerfs, consisting of four sentences, translated by my friend Jan Adriaenssens: “Within erven and woonerven:

- “Pedestrians can use the full width of the public road; and playing is also allowed.”

- “Drivers may not endanger or obstruct pedestrians. If necessary, they must stop. Furthermore, they need to be extra careful regarding children. Pedestrians may not obstruct traffic unnecessarily.”

- “Speed is limited to 20 km per hour.”

- “Parking is forbidden, except where there are visual markings like different surface colors, a letter P or traffic signs allowing parking.”

Rather than setting out specific requirements for drivers and pedestrians, as in the Belgian law, SB 5595 simply exempts pedestrians from the section that describes how they need to behave in the presence of cars and replaces it with a hierarchy of priority that puts pedestrians at the top and cars at the bottom. Notably, the speed limit enabled by SB 5595 is even lower than the one defined in Belgian law (10 mph in Washington State vs. 12.4 mph in Belgium).

Existing standards

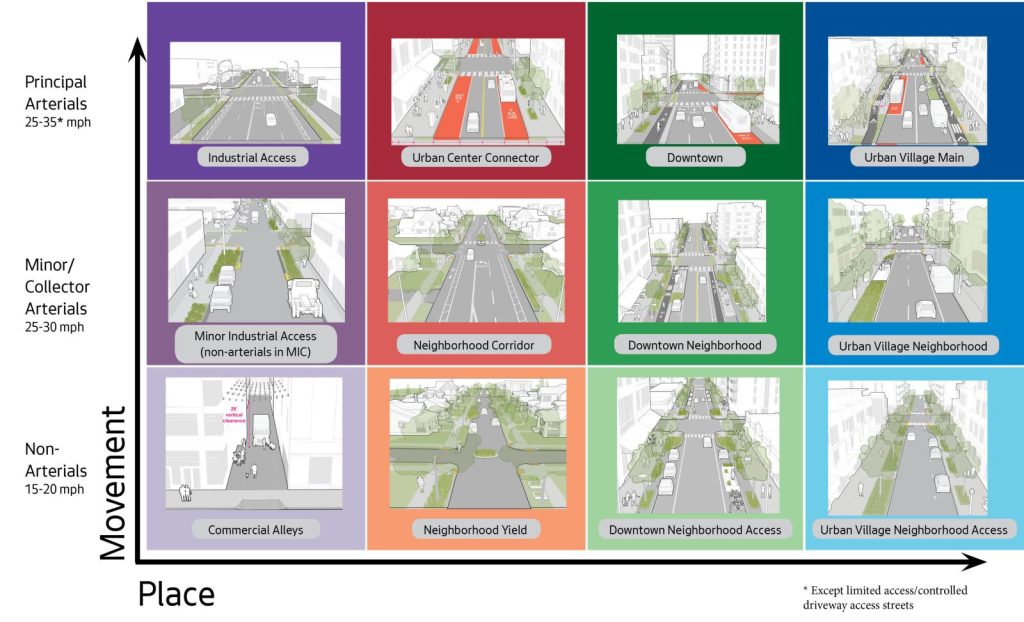

With Washington State on the cusp of being the first jurisdiction to define and legalize shared streets, one would assume an organization like WSDOT or SDOT would bear the burden of developing standards and guidance for local jurisdictions. Seattle’s right of way improvement manual, called Streets Illustrated, doesn’t include guidelines for the design of shared streets.

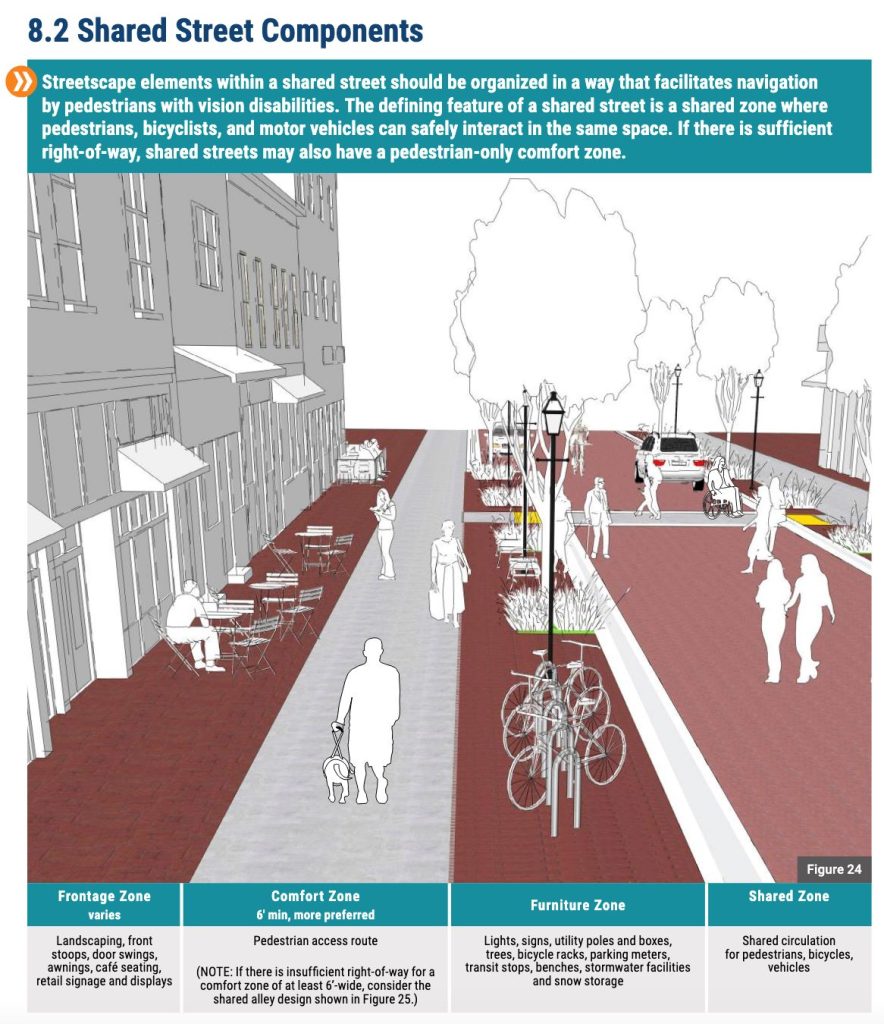

Fortunately, both the National Association of City Traffic Officials (NACTO) and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) have useful guidance already. The FHWA’s publication, Accessible Shared Streets: Notable Practices and Considerations for Accommodating Pedestrians with Vision Disabilities is full of useful ideas.

That publication is focused on making shared streets more navigable by people with vision impairments but it covers a range of physical attributes and considerations that benefit all users. The examples show shared roadways that are too wide and lack the kind of physical barriers like bollards that provide the most comfort for pedestrians in shared environments but the document highlights a number of useful features:

- Portal treatments like raised crossings that slow vehicles entering the shared space. Aggressive neckdowns that narrow the entrance are also useful measures.

- Signs indicating pedestrian priority. Since shared streets are new, it is especially helpful to include signage that clearly spells out the speed limit and pedestrian priority.

- Generous comfort zones on wider shared streets. Pedestrians have the right of way in every part of a shared street but not all of the shared street should be shared and, where width allows, areas should be provided where pedestrians can enjoy refuge from the shared portion of the roadway. Even the narrowest shared streets have room for a bollard or other hardscape element.

Now what?

The Shared Streets Law goes into effect 90 days after the end of the legislative session, at which point local authorities will have the freedom to create shared streets. The local authority in Seattle, for example, is the City Council.

Seattle could take a number of possible approaches. For example, the city could designate streets as shared streets only when they have physical attributes somewhat consistent with that designation, like Bell Street. This is an infrastructure-first approach that would ensure no street is shared until its physical design supports the designation.

At the other end of the spectrum, if we want to be aspirational and bold, the city could designate every non-arterial neighborhood street a shared street. We’ve done this before, in 2016, when Seattle dropped the default speed limit on non-arterial streets from 25 miles per hour to 20 miles per hour. Doing this again, except dropping the limit to 10 miles per hour and allowing pedestrians to walk in the center of the street, would be bold indeed. While it is beneficial to allow shared streets to spread far and wide, drivers and pedestrians will need a chance to get used to the new regulatory framework. The number of signs alone that would be necessary to properly mark every new shared street under this approach would be vast.

A middle path between these two extremes could be to target every green street, festival street, healthy street, and neighborhood greenway, plus places like Ballard Avenue. Many of these streets are already signed “Street Closed” to allow pedestrians to legally walk in the roadway.

Lastly, an approach that is aspirational but equity-focused, would be to designate every non-arterial neighborhood street without sidewalks as a shared street. In Seattle, these streets exist primarily in the southern part of the city and north of 85th Street. Due to the lack of sidewalks, these are shared streets already. A shared street designation could change the balance of power, at least in a regulatory sense but this would need to be followed up with actual physical interventions to ensure compliance with the lower speed limit and safety for people walking in the street.

The passage of Washington State’s Shared Streets Law marks a historic step toward reclaiming public space for people, not just cars. Cities in every corner of Washington State now have a new tool that allows them to dramatically drop speed limits, prioritize pedestrians, and enable a range of innovative street designs. Their challenge will be to use that tool to reshape neighborhoods for the better.

Mark Ostrow serves on the board of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways and is a core leader of Queen Anne Greenways. Follow him on Bluesky at @qagggy.