Complicated calculations determine if affordable housing gets built on King County’s Eastside. A Regional Coalition for Housing (ARCH) finds itself in the middle of it all.

Constructing affordable housing in the cities on the east side of Lake Washington has always been a challenge, thanks in part to high real estate prices, restrictive zoning and regulations, and more limited funding sources compared to Seattle. And though some municipal policy changes in the past five years have helped ameliorate the situation, other factors still make it extremely challenging to fund, permit, and build affordable housing on the Eastside.

A Regional Coalition for Housing (ARCH) is the fulcrum of affordable housing efforts on the Eastside, having built more than 9,000 units since its inception in 1992. Since ARCH is set up as a council of governments, with key leaders from the 15 Eastside cities composing its various boards, its policy guidance is hard to undo once it’s been made. It’s an efficient system when ARCH is on the right track, but critics contend that organizational structure contributes to ARCH’s processes being hard to course correct and opaque.

While those governments are free to adopt their own policies, ARCH’s recommendations hold substantial clout. ARCH’s monthly board meetings are not posted publicly – one has to email the organization to seek permission to listen online.

Getting housing policy right is crucial, as local housing prices spiral out of reach for working families and the risk of a housing slowdown grows. According to Apartment List, median rent for a one-bedroom apartment is currently $2,188 in Bellevue, $2,081 in Kirkland, and $2,062 in Redmond — that’s higher than in Seattle, where the median one-bedroom is $1,924.

Though a boom in apartment construction in the past several years has actually led to a decrease in median rents in Kirkland (-1.8%) and Redmond (-1.1%) in the past year, the pace of construction of market-rate and subsidized multifamily housing is expected to slow considerably. Even with the apartment boom, many families find themselves entirely priced out of the for-sale home market, as average home prices have climbed well north of $1 million in most Eastside cities.

Angela Rozmyn, sustainability director at Natural and Built Environments, a Kirkland-based development firm (and also a member of the Kirkland Planning Commission) says that the Eastside is now in a housing recession, especially with regard to multifamily projects. “We’re still seeing quite a bit of single-family housing, but when you talk about larger projects, those have mostly been put on hold at this point,” Rozmyn says.

“It’s hard, because people see construction going on and lots of cranes,” she says. “But what you don’t see are the applications that aren’t showing up, you don’t see the design review board meetings that aren’t happening.”

Two additional pressures are adding to the difficulty:

- Parking requirements that drive up the cost of affordable housing projects, and

- Mandated affordable housing contributions, which include increasingly strict area median income (AMI) requirements as part of mandatory inclusionary zoning.

This confluence of factors is making it increasingly difficult for developers to make projects pencil out as feasible.

Unlike Seattle, Eastside cities lack a housing levy or a payroll tax dedicated primarily to housing to provide a steady source of revenue to fund affordable housing creation. As a result, the Eastside is more dependent on developer mandates and corporate philanthropy to make affordable housing happen. In the last few years, Microsoft and Amazon have announced billion-dollar housing pledges to provide affordable homebuilders low-interest loans and grants. But the mix of corporate loans, philanthropic gifts, state grants, and federal tax credits isn’t necessarily enough to get projects off the ground in the absence of City contributions.

Rozmyn notes that high interest rates, steep land and labor costs, and changing regulations are hindering the creation of both affordable and market rate housing on the Eastside. Kirkland is falling well behind on its goals to create more affordable housing, she said.

“A project [in Kirkland] that was originally planned to be 600 apartments is now being built out as 100 luxury townhouses, which to me is extraordinarily disappointing,” she said. “It means that we really have failed as a city.”

Nevertheless, late last year, the Kirkland City Council took small steps to encourage walkable neighborhoods in its 20-year growth plan, but made no major zoning changes. Kirkland is in the process of upzoning two large sites in the Juanita neighborhood to accommodate up to 770 homes.

The city has had decent success building accessory dwelling units (ADUs) after Kirkland (and Kenmore) approved reforms making it easier to build ADUs in 2020. Kirkland has also been ahead of the curve on House Bill 1110, which requires upzoning near transit: the city had already reformed zoning to allow cottage housing, duplexes and triplexes.

But Kirkland has created about 1,400 new units of new affordable housing since 2019, well short of what was supposed to be a goal of 2,500 by the end of 2025.

Other cities in the region are slowly starting to take a more proactive approach to affordable housing. The city of Bellevue launched a new Office of Housing in February after passing a one-tenth-of 1% sales tax to fund affordable housing and services in 2021. Bianca Siegl, Bellevue Office of Housing director, says Bellevue has two surplus city properties it’s hoping to develop into affordable housing – one in the Bel-Red neighborhood and one in Wilburton.

“We’re currently in the application period and looking to develop, between those two sites, around 400 units of affordable housing,” Siegl said.

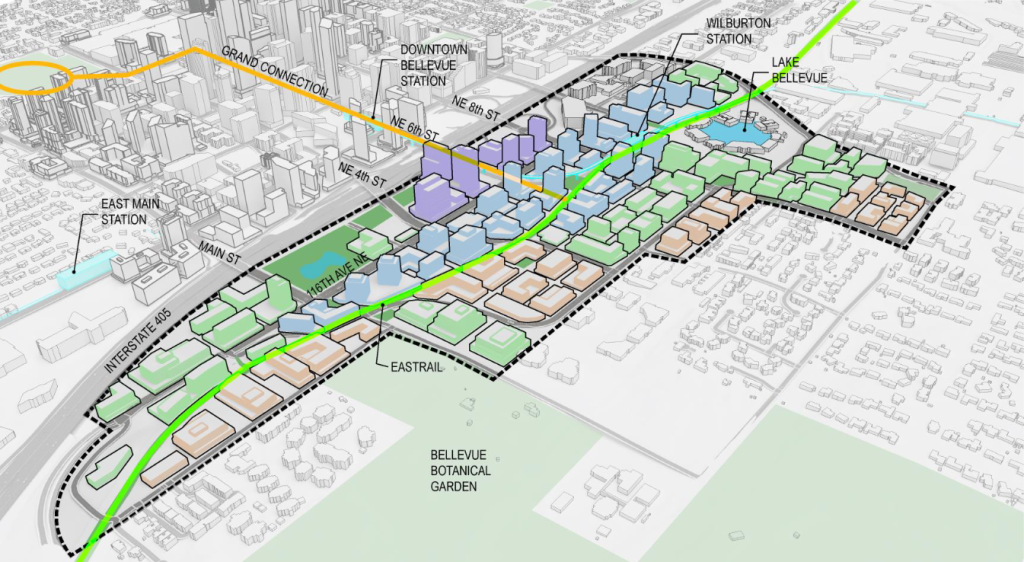

Wilburton, the site of a recently opened Link light rail station, is key to Bellevue’s strategy for affordable housing and transit-oriented development (TOD) as well as its newly adopted 20-year growth plan. The Wilburton Vision plan, launched in 2021, imagines a walkable, relatively dense, transit-oriented neighborhood in the Link station east of downtown. In the past two months, the city council has been debating and finalizing plans for zoning and planning changes, and an inclusionary zoning plan.

That plan, which the city council is expected to vote on soon, would require one of three options on all multi-family rental projects constructed in the Wilburton neighborhood: 10% of units at 80% AMI, 7% at 60% AMI, or 5% at 50% AMI.

Kenmore, under the leadership of Mayor Nigel Herbig, has also expanded its focus on affordable housing, working with A Regional Coalition for Housing (ARCH) to fund and permit a variety of projects, including two in the pipeline: The Approach at Kenmore, a 121-unit development with multifamily housing for those earning 50 to 60% AMI, and Larus, a 175-unit affordable housing project for seniors. That project received $3.6 million from ARCH’s housing trust fund.

However, Kenmore has been more hesitant when it comes to affordable housing specifically geared toward people who were previously homeless. In late 2023, the Kenmore City Council blocked a development agreement with Plymouth Housing to add 100 units of permanent supportive housing on a City-owned parcel, bowing to local pushback. Instead, Redmond swept in to take on the project.

Kenmore was hardly unique in levelling extra scrutiny on facilities for homeless people and scaring off some low-income projects. For example, Bellevue delayed a homeless shelter for men for roughly a decade due to local pushback before finally opening it in 2023.

Since its founding in 1992, ARCH has grown into a collaboration among 15 cities on the Eastside and King County that funds and develops affordable housing.

“They have a tough role, where they’re working for a bunch of different cities and trying to balance all of the various views of different cities,” Herbig said. “But they’ve done a good job at getting units stood up. Their record of leveraging outside funds is phenomenal.”

Sharon Lee, the director of the Low Income Housing Institute, says her organization has worked with ARCH on two affordable housing projects in Bellevue – the 68-unit Aventine project, which rehabilitated an existing apartment building into units affordable to families earning below 30, 50 and 80% AMI, and August Wilson Place, a 57-unit affordable housing building that opened in 2015.

“My opinion of ARCH has increased a lot since the old days,” Lee said. “In the old days ARCH had very little money, and so you’d have to apply and reapply.”

Though no one would go on record with The Urbanist to directly criticize ARCH, housing activists and developers say the organization has a reputation for being less than transparent. Case in point: ARCH declined to be interviewed by The Urbanist for this article.

Another criticism leveled by housing activists at ARCH is its fondness for requiring parking in affordable housing projects.

In February, 2023, the Kirkland Planning Commission met to consider zoning code amendments for the 85th Street Station Area, a dense, mixed-use urban area near a new Sound Transit “S2” bus rapid transit route expected to open in 2029, following a series of delays. Among the proposals brought to the commission by city staff, which documents show was in direct consultation with ARCH, included a recommendation for a 0.75-to-1 ratio of parking stalls per one bedroom unit of affordable housing. The station area plan exempts studio and one-bedroom apartments from the parking requirements, but multi-bedroom apartments continued to face them.

In addition, the City of Redmond has a complicated set of parking policies with respect to affordable housing, whether Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE) units or otherwise, apparently at the advice of ARCH. Buildings with a parking ratio of 0.75 stalls per home or greater are required to reserve a proportional amount for the affordable units and offer those stalls at a discounted rate, although buildings with lesser parking ratios do not face this requirement.

“The binding covenants (which ensure that the dwelling units designated as MFTE affordable units would in fact be operated as affordable units) for mixed-income developments contain boilerplate language requiring a minimum of 1 parking stall per affordable unit,” Christina Wilner a spokesperson for the City of Redmond told The Urbanist. “However, the MFTE program defers to the zoning code for parking. As such, for those mixed-income MFTE developments with a parking ratio of parking stalls per dwelling unit greater than 0.75 (averaged across the entire project), then a corresponding proportion is reserved for affordable homes at a discounted rate. If the mixed-income MFTE development has a parking ratio equal to or less than 0.75, then no special parking provisions apply for allocation of parking stalls to affordable housing units.”

But with Governor Bob Ferguson signing a statewide parking requirement reform law earlier this month, Kirkland and Redmond’s mandates on affordable housing builders will be overridden and invalidated in most cases by 2027.

According to the new state law, cities with a population over 30,000 cities can only require a 0.5 parking stalls per home in market rate projects and can no longer require any parking for affordable housing units – making ARCH’s recommended policies in Redmond and Kirkland moot (Kirkland, Redmond, and Bellevue all exceed the 30,000 population mark – only Kenmore is below that figure, with a population of about 24,000).

“Providing parking is expensive for any project,” said Bellevue housing director Siegl. “While Bellevue is in the process of a major transition to a more TOD-focused development pattern, in certain nodes, we are not now in a place where we’re going to be removing parking requirements. But there are incentives in place for affordable housing that reduce parking requirements near transit.”

“Bellevue City Council, Planning Commission, and staff leadership have been great partners as we continue to work hard to help ensure rezones and code changes reflect the ‘new normal’ in today’s very challenging real estate market,” said Bellevue Chamber of Commerce CEO Joe Fain. “What worked six to eight years ago, when interest rates were at zero and construction costs were favorable, doesn’t work anymore – and likely never will.”

Herbig said he supports Kenmore loosening requirements for parking, “Every additional parking space adds cost to development — $70,000 to $100,000 if you’re talking about structured parking and $15,000 to $30,000 for surface lots,” Herbig said. “And you also consider the buildable area and all of that.”

In addition, Kirkland city staff, on the advice of ARCH, in 2023 made Kirkland’s inclusionary zoning program in the 85th Street Station Area rezone so difficult to qualify for that no apartments have been built there since the zoning changes.

Bumping up from a longtime standard of requiring 10% percent of units to be available at 80% AMI, Kirkland voted to change the AMI for the 85th Street Station Area to a threshold to 50% AMI and to base the percentages of required affordable units on building heights: 10% to 15% for buildings under 65 feet tall, and 20% to 25% for buildings more than 65 feet in height. These percentages are not effective until

624 units are created in the station area.

A group of developers, in a strongly worded letter to the city of Kirkland in April 2023, faulted the 85th Street Station Area rezone, claiming it only looked to future market conditions. “Adopting code that is predicated upon future, wholly speculative market changes that would be necessary for any projects to move forward will have a strong chilling effect on Kirkland’s multifamily market,” the group said in its letter. “Kirkland should work with developers to adopt something that pencils today and will yield the desired outcome for everyone.”

“[The planning commission] went through a big station area workplan a couple years ago,” Rozmyn noted, “and we have not seen a single apartment project happen since those rules were updated.”

The city of Redmond has also lowered the AMI thresholds for its Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE) programs – with the stated goal of creating more deeply affordable units. But as Seattle’s experience has shown, lowering the AMI levels doesn’t necessarily encourage the building of affordable units, and in fact often makes it harder for developers to make the project pencil out – and as a result either decline to participate in voluntary programs or simply not build market-rate projects in areas where strict inclusionary zoning requirements are in place.

Redmond, which is rapidly increasing density and just opened two new light rail stations on the 3.4-mile extension of the Link, has a mandatory inclusionary zoning policy that requires all new multi-family apartment projects to dedicate 10% of units at 80% AMI, with higher requirements in the Overlake growth center.

Its MFTE program, which began in 2017, initially offered the voluntary tax incentive as an option for projects in downtown, Overlake and Marymoor. This included a voluntary program that offered an 8-year tax exemption for 10% units at 60% AMI or a 12-year exemption for 20% at a mix of 65 and 85% AMI (the rate was slightly more restrictive for Marymoor).

In 2023, Redmond briefly eased its 12-year tax incentive MFTE program, giving breaks to projects that offered 20% of units at a mix of 80 and 90% AMI.

But in 2024, as part of its 2050 comprehensive plan, Redmond made MFTE programs more stringent, with downtown 12-year incentives increasing to 20 percent at a mix of 50 and 80%, Marymoor’s eight-year program increasing to 15% at 80% (and the 12-year incentive eliminated) and Overlake’s eight-year incentive raise to 12.5% at 50% AMI, and its 12-year incentive eliminated.

MFTE is a voluntary incentive program that, when used well, creates new middle-income housing, said local land use and housing consultant Natalie Quick. “In this market, if AMIs are too low in a MFTE program, one of two things will happen: the MTFE program doesn’t get used and the municipality doesn’t benefit from the middle-income housing or, if the tax incentive is needed to make the project pencil and it can’t be considered because the requirements are too stringent, then the project isn’t built until rents on the non-MFTE units rise high enough to offset the MFTE requirements.”

The upshot is that all these changes Redmond and Kirkland have made in the interest of promoting more affordable housing have sometimes ended in discouraging affordable units and even the creation of market–rate apartments. And it turns out that since 2020, Redmond’s MFTE program hasn’t generated all that much housing: resulting in just 310 affordable units (60% AMI or less) over the past six years. According to Christina Wilner, a spokesperson for the City of Redmond, there are currently 131 affordable units in the pipeline – and all are in downtown, and all built through the eight-year incentives that haven’t changed since the program’s inception.

Still, some activists are optimistic things will change and that Eastside cities will ramp up efforts to create affordable, transit-oriented units. Jazmine Smith, director of advocacy for Futurewise, views Bellevue’s Wilburton rezoning plans, once they’re passed by the city, as a good model for the Eastside. (Smith also serves at The Urbanist Elections Committee co-chair.)

“I think that we’ll have a huge win in Wilburton,” Smith said. “I’m excited to see how City Council will move forward with the final legislation. I think that with the eco-district, and transit-oriented development districts they’ll be enacting with this vision they will really be able to set the stage for a great deal of affordable housing being built into the code.”

Kenmore Mayor Herbig, however, believes that until the county comes forward with at least a billion-dollar housing levy or the state significantly boosts funds for affordable housing, the Eastside won’t really begin to address its affordable housing deficit.

“I’d love to see the county step up with a really big housing levy, because I think that’s the only way we’re going to get what we need,” he said. “We’re so far behind. We’ve been not doing our jobs for the last 50 years, and what we have to do is astronomical.”

Correction: The original draft stated Bellevue’s homeless shelter broke ground in 2023, but that is the year the project opened. On June 4, the article was updated with additional information from ARCH, which belatedly responded to The Urbanist’s inquiries, and a clarification from the City of Redmond around parking requirments.

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.