Years of added delay and well over budget, Sound Transit’s Stride bus rapid transit (BRT) program is now adding more stress on the larger Sound Transit 3 program. Agency boardmembers are still moving the program forward, but that didn’t stop them from expressing a lot of concern and frustration about it.

In early July, an exasperated Claudia Balducci, chair of the agency’s System Expansion Committee, bluntly said, “You’re asking for us to add $200 million and several years to a project that was supposed to be the cheap fast one.” That was in reference to a then-proposed budget and schedule action for the program, known as “baselining” in Sound Transit parlance. Costs of the program have risen another $200 million in mere months, but larger cost increases have been years-in-the-making.

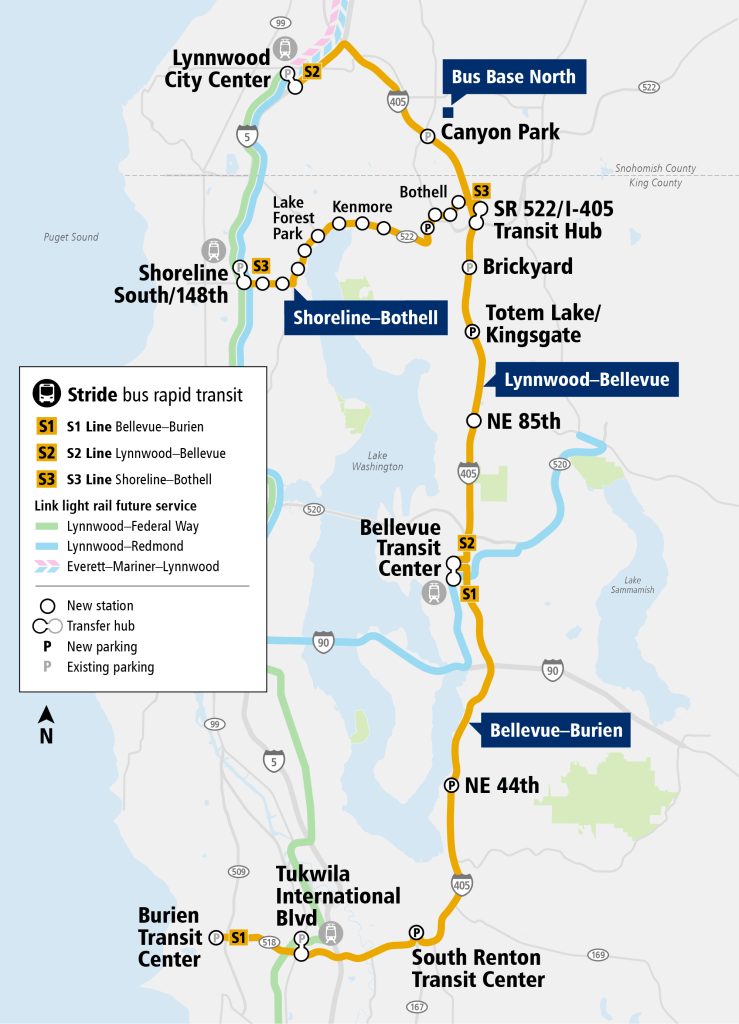

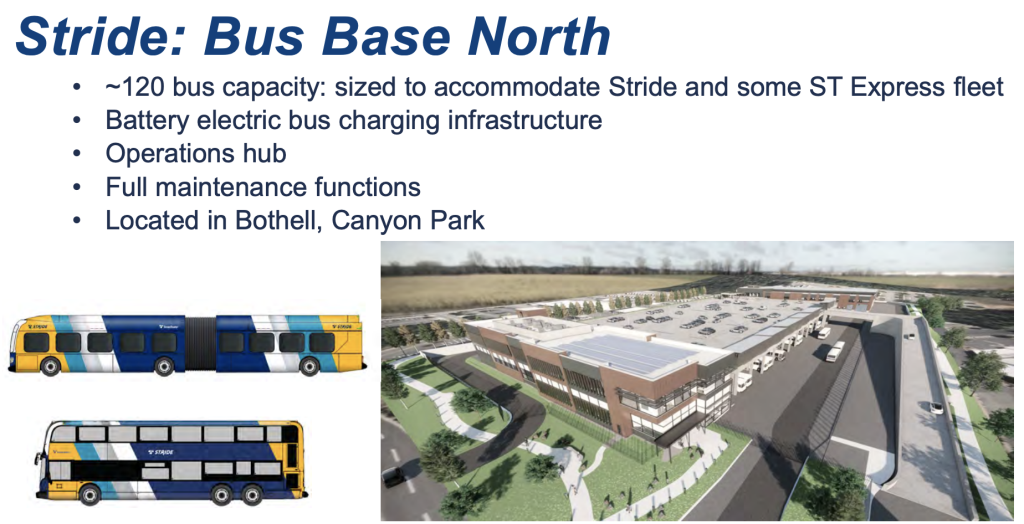

In a period of just three months, Sound Transit staff also unloaded an extra year or two of delays in delivering the program. With a high level of uncertainty remaining, staff are now projecting the four principal project elements to open as follows: late 2027 for Bus Base North, mid-2028 for the S1 and S3 Lines, and mid-2029 for the S2 Line.

Stride’s cost increases are staggering with questionable expenditures

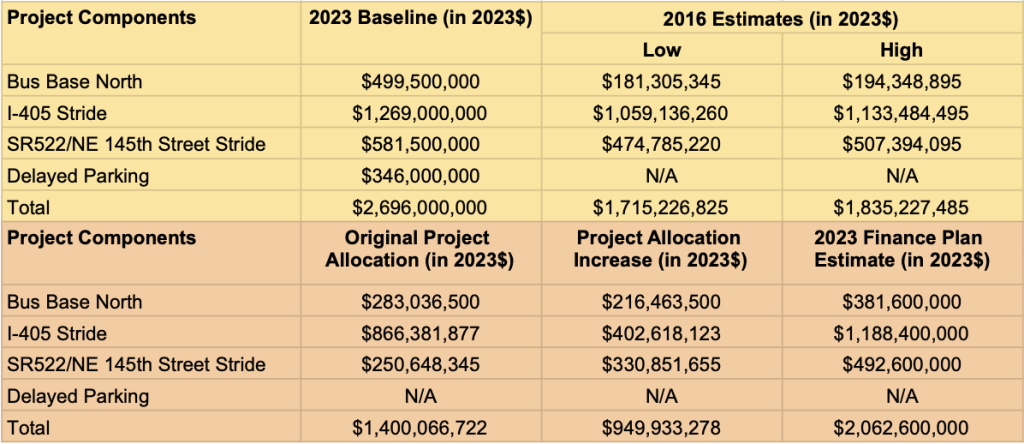

Baselined cost estimates of the Stride program are staggering, reaching 32% higher than assumed in 2016 — and that’s controlling for inflation. Total project costs are now projected to top $2.7 billion, well above the original cost estimate range of $1.7 billion to $1.8 billion.

Just since the spring financial plan update, cost estimates have risen between 7% and 31% with the Bus Base North project component being hardest hit. In mere months, that project element has managed to register another $117.9 million in added costs on its own. But even more distressing is that project allocation costs are jumping 32% to 57% higher, depending upon project component.

General inflation has certainly driven a hefty chunk of the cost increases along the way, but Sound Transit has also recently laid blame on higher fleet acquisition costs and fish barrier removal as cost drivers too. Those latter two costs are the consequence of staff choices though.

Battery-electric buses not only cost more per unit than conventional buses, but also have much higher related infrastructure costs and necessitate more spare vehicles due to their high unreliability rates. And fish barrier removal costs have only become an issue because Sound Transit is helping the state expand its highways. However, those added costs (estimated to account for up to $125 million) really pale in comparison to the overall project scope creep and unfavorable bids that have pushed program costs through the roof.

By and large, the program baseline action does not account for future program costs associated with parking. That aspect of the program will be delayed well into the 2030s and 2040s and will ultimately add $346 million in costs for about 1,800 parking stalls in structured parking facilities.

Put another way, Sound Transit is poised to spend about $200,000 per parking stall even though the most of riders will never use that parking to access the Stride system. It begs the question if this expenditure will ever be a prudent use of limited transit dollars over just investing in walking, rolling, and biking infrastructure near stations and purchasing connecting transit service through fixed-route buses and flexible on-demand options like Metro Flex.

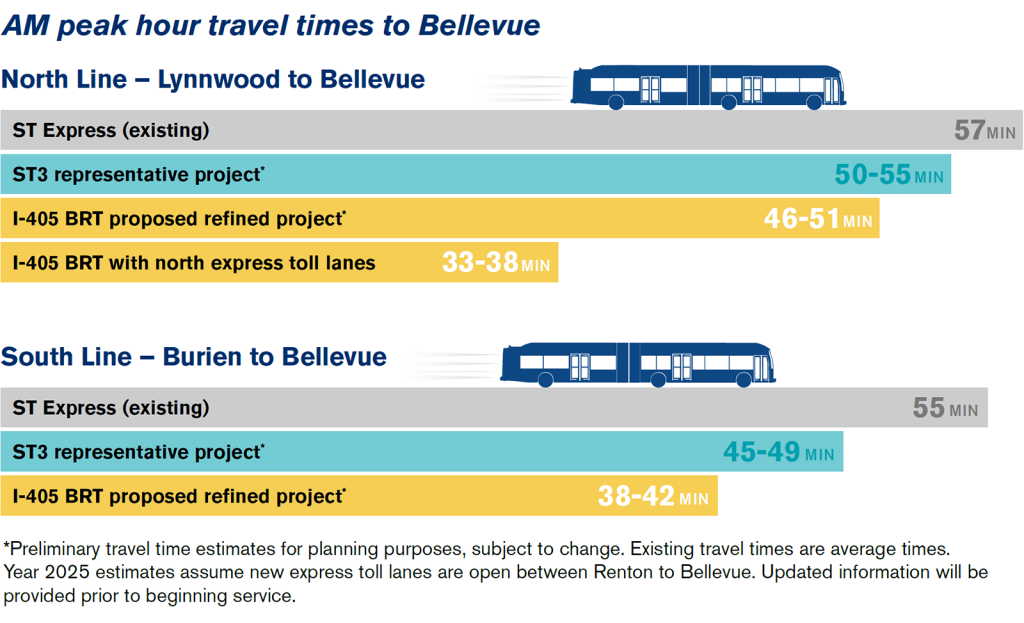

Piggybacking on WSDOT’s I-405 expansions are a costly choice

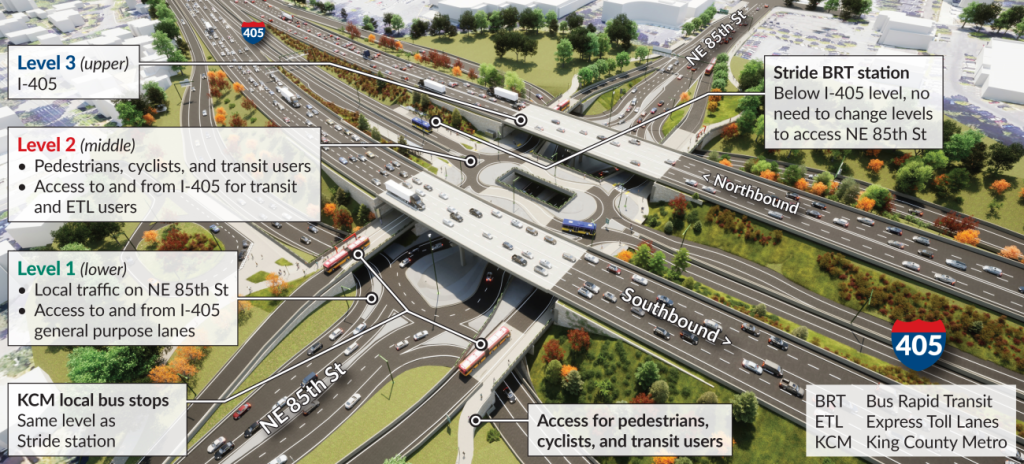

A few years ago, Sound Transit staff unveiled promising project scope changes predicated on partnerships with the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT). Those partnerships primarily centered on I-405 where WSDOT had been planning to expand express toll lanes (ETLs) and build new direct access ramps. In doing so, Sound Transit could move freeway stations toward the median and build them “inline” so that buses could have direct access to ETLs. The idea behind this was that buses wouldn’t have to navigate in and out of ETLs to stations near the outside of the freeway, likely via congested ramps, and thereby reduce travel time and improve reliability.

The problem with piggybacking on WSDOT’s ETL projects is that they are very behind schedule and have come in at astronomically high prices. Sound Transit, for instance, is spending over $287 million on the NE 85th Street/I-405 interchange in Kirkland just for the privilege of building a small freeway station pair. WSDOT, for its part, recently determined that a bid from Skanska to do a design-build of Bothell area I-405 ETLs, interchange modifications, and Stride facilities was of apparent best value, but that bid was nearly 40% above last fall’s cost estimates.

Building the project schedule around the WSDOT’s I-405 projects has been a big drag on the Stride program and now it’s hitting the budget hard.

Cutting corners, blunders, and missed opportunities plague the program but could be lessons learned

Along the way, Sound Transit staff made many other blunders and tried to cut corners on the margins where it never made sense.

Progress on delivering Bus Base North, for instance, has been slow and mired in one delay after another. Staff have consistently blamed planning delays, local covenants, and permitting approvals as factors holding it up. But base development and fleet acquisition have also seen scope creeps, complicating and slowing delivery. In a better managed program, this would have been delivered on-time to allow for the other Stride projects to come online in 2024, even if that had meant delivering other elements of those projects later.

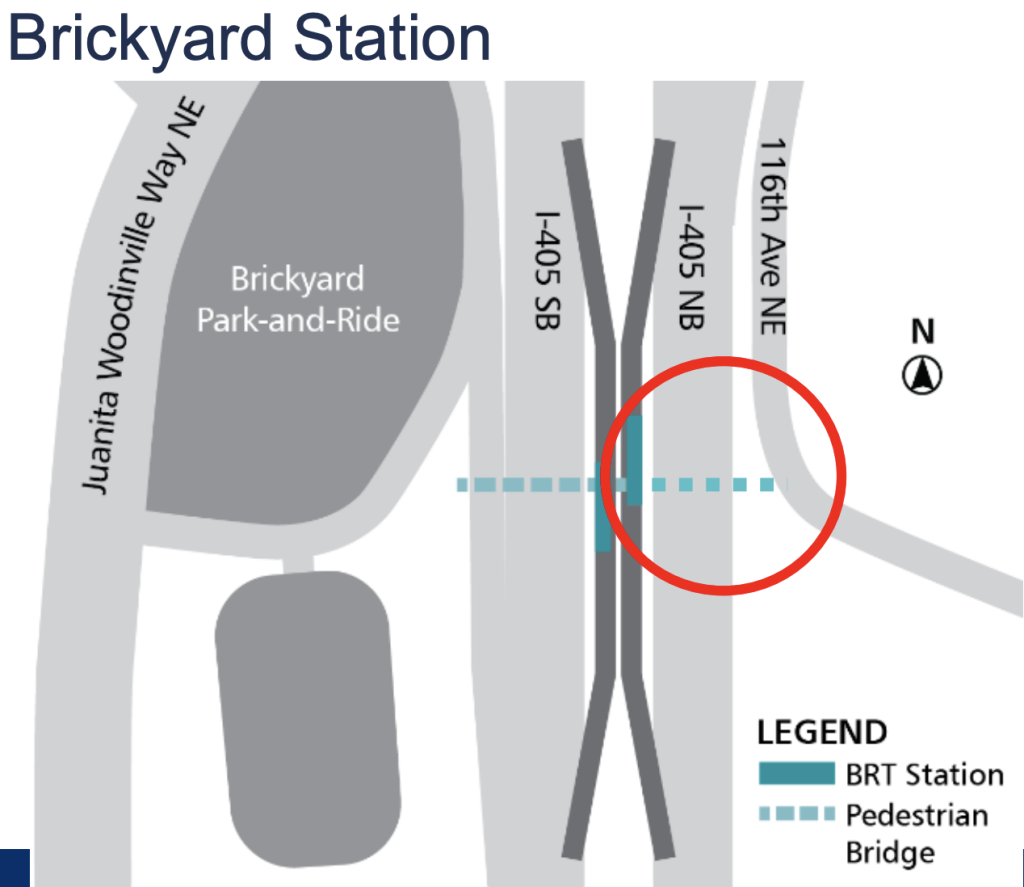

In 2021, agency staff proposed cost-cutting measures as part of a value engineering process. The goal was to help make the Stride program affordable. Among those cost-cutting measures, however, were draconian proposals to worsen the rider experience for a mere $15 million to $20 million.

Agency staff proposed dropping half the pedestrian and bike bridge over I-405 from the Brickyard inline freeway station and partially cutting back another one in Tukwila. Those access cuts didn’t happen in the end, but it was a pennywise approach to salvaging a program with much larger problems. And now, in a twist of fate, the agency has actually partnered with a private developer to extend the Tukwila International Boulevard station bridge further — that developer will contribute $5 million to $7 million to the project.

And then there is the controversial section of the SR 522/NE 145th Street (S3 Line) project in Lake Forest Park. Local residents and politicians have put up a fight to block it, slowing down its progress and complicating permitting. Sound Transit’s intended investments in the segment would take a significant amount of private property to expand the road for a new northbound bus lane.

In retrospect, it appears that staff could have simplified the S3 Line project by converting an existing lane to a transit or business access and transit lane, negating the hefty $102 million cost and controversy over property takings and streetscape impacts. WSDOT Secretary Roger Millar all but gave the blessing in his comments to staff in November, but staff screened out the possibility earlier in the design process and now the agency is faced with considerable challenges to deliver a critical segment of the overall project.

In her comments at the July System Expansion Committee meeting, Committee Chair Claudia Balducci seemed to pick up on that issue. She couched those comments as an idea that’s been in discussion.

“Do we really have to widen the road so much,” Balducci asked. “Can we shrink the size of the lanes? That would slow things down, but is slowing things down a bad thing or would that make for a safer road and more competitive transit service?” Agency staff didn’t have a response to this, but smaller roads with fewer general purpose lanes tend to increase safety for all road users while repurposing existing lanes to transit naturally makes transit a more attractive option.

In the course of the discussion, Fife City Councilmember Kim Roscoe noted that Pierce Transit has been experiencing similar issues to Stride with their BRT project, dubbed Stream. Costs for the project have skyrocketed, forcing the agency to propose dramatically trimming back the project scope. Real estate acquisition prices for bus facilities and private car capacity enhancements conditioned by partner agencies like Tacoma and Pierce County made the original project approach financially infeasible. But as Balducci pointed out, Pacific Avenue/SR 7 — the road that Stream’s first line would run on — has “a lot of pavement to work with” and that lanes could easily be rechannelized to facilitate buses.

Perhaps both Stream and Stride are teachable examples for the region that bus rapid transit projects will face significant hurdles if the primary method to attaining partial or fully exclusive right-of-way is to build new right-of-way rather than scoping projects to require partner agencies repurpose existing right-of-way.

Stride is stressing ST3’s financial viability and is a warning

Now the cost increases are coming to bear on the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) program in a serious way. The baselining action alone is cutting remaining debt capacity from 15.9% to 13.7% and debt service coverage ratio from 1.67 to 1.62. Though that may seem small, it’s a stark warning that the remaining debt flexibility could be exhausted in the not-so-distant future. If and when that happens, the overall ST3 capital program would become unaffordable again forcing the agency to further delay projects and consider other ways to make it become affordable.

In last month’s System Expansion committee meeting, Kim Roscoe picked up on this ahead of votes on the baselining motions.

“This Bus Base North baseline takes our net debt service coverage ratio to 1.65 and our policy minimum is 1.5,” Roscoe said. “It also reduces our debt capacity and I want to hear from staff or CEO about confidence or advice on as we’re moving forward on making decisions in the next 10 or 12 years about these other huge projects, what can the public and agency expect?” Staff responded that the agency is taking actions to try and mitigate this challenge, but it could ultimately affect future capital project actions.

To be sure, Sound Transit does have tools at its disposal to relieve some debt pressure now and in the future. But the agency’s board is facing down a firehose of other baselining actions and budgetary requests poised to come forward in the next few years. Those that are all but sure to put more stress on capital program finances, especially if a few Link projects come in over-budget anywhere close to Stride. That could eviscerate remaining debt capacity and service capabilities.

During the committee meeting last month, other agency boardmembers raised many questions and concerns with project costs.

University Place City Councilmember Kent Keel expressed a desire to send the baselining motions on without a do pass recommendation. “The only reason I raise [this] is because of the conversation we should have at the full board about all the questions as a committee we still have that haven’t been answered,” he said.

Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers followed up to say that he felt that it was “a good conversation that the whole board needs to have about all the projects and impacts of delays across the whole system, the impacts of increases in construction costs, labor costs, etcetera.”

Committee Chair Claudia Balducci said she needed to understand in detail why costs have been skyrocketing, predicating her full board vote on that information. “This is a lot of money and we’re asking people to wait a very long time and we need to break down why that is so that, after baselining, the board can be helpful and taking actions to improve the situation,” she said.

Keel, in a rare occurrence, resisted in referring most of the Stride baselining motions to the full board meeting with a do pass recommendation. It wasn’t enough to stall any of them in committee or change them to without recommendation — ultimately they were all approved by the committee and full board — but it was a clear signal that there is now some hesitance to rubber stamp mismanaged projects. Whether or not that will give agency staff real pause about how they proceed with project development for other capital programs in the works remains to be seen, but the Stride program may be a chilling warning of things to come as design work advances on more complex Sound Transit 3 projects.

For many transit supporters, the Stride program will surely be a case study on the many ways not to do a bus rapid transit project. But when it finally reaches completion, it will provide meaningful transit service improvements along the I-405 and SR 522 corridors. And in time, perhaps the projects will encourage car-light, transit-oriented development around stations.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.