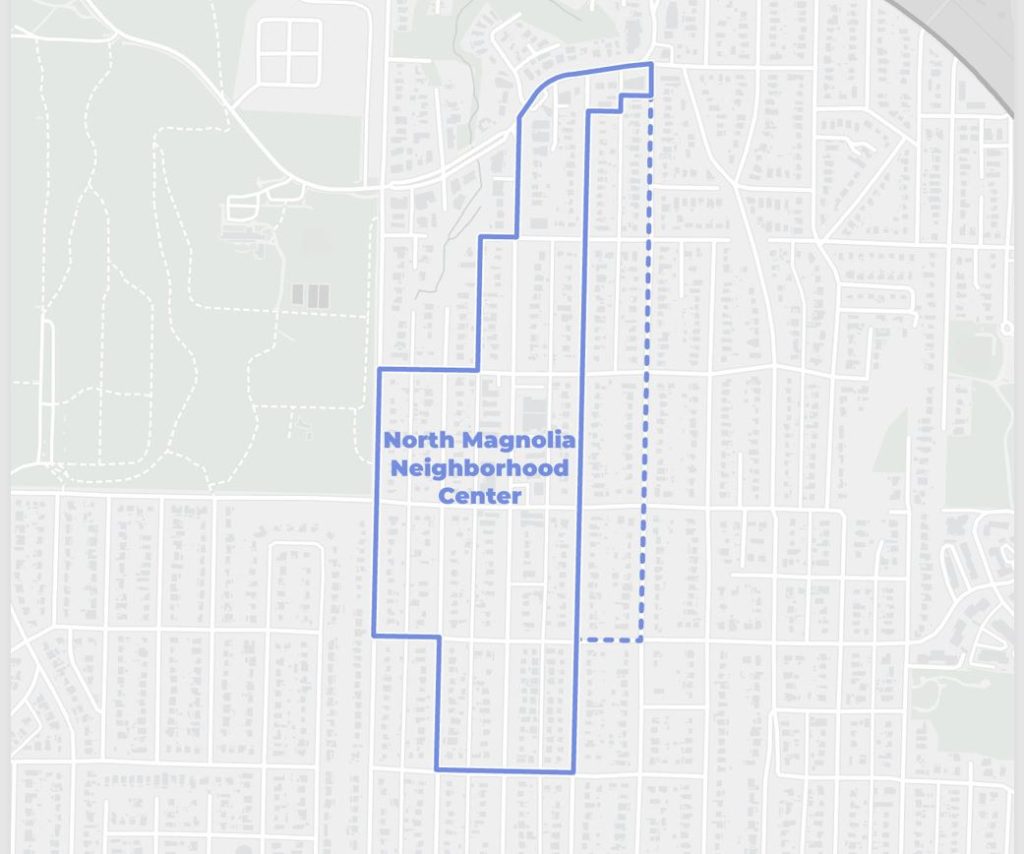

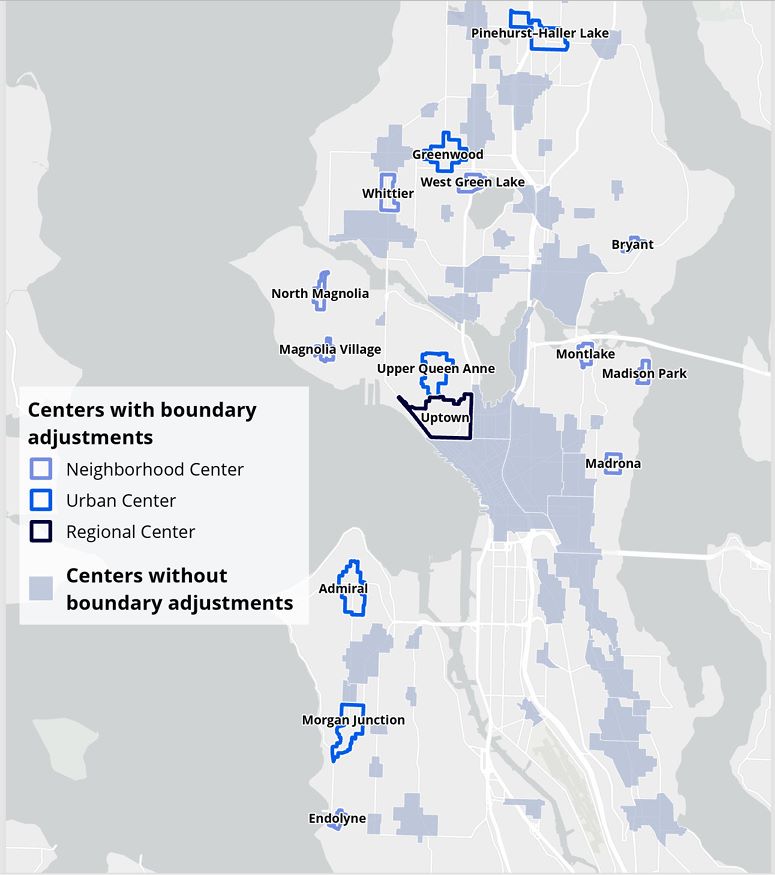

As the Seattle City Council starts to fully dig into Mayor Bruce Harrell’s proposed One Seattle Comprehensive Plan, the city’s top planner is defending a recent move to scale back increases in potential housing capacity in Seattle’s wealthiest areas. Ahead of the final transmission of the plan to the council, dozens of blocks were chopped off the boundaries of 14 growth centers, a central part of the strategy to allow additional types of housing in areas of the city that have traditionally been off limits to anything but single-family homes.

Last week, Michael Hubner, the long-range planning manager at Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) shepherding the One Seattle Plan, visited the city’s planning commission, walking through the changes, first reported by The Urbanist in late May. He minimized the reductions, which came after sustained opposition to more housing from residents in neighborhoods like Magnolia, Green Lake, Madrona, and Fauntleroy.

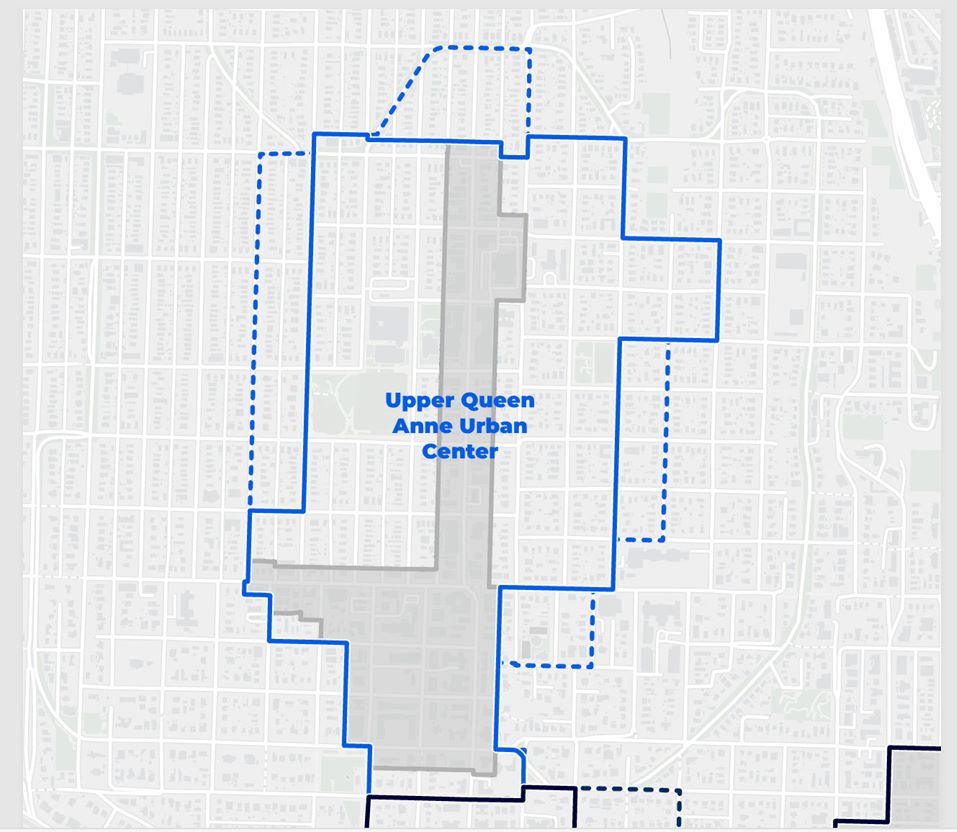

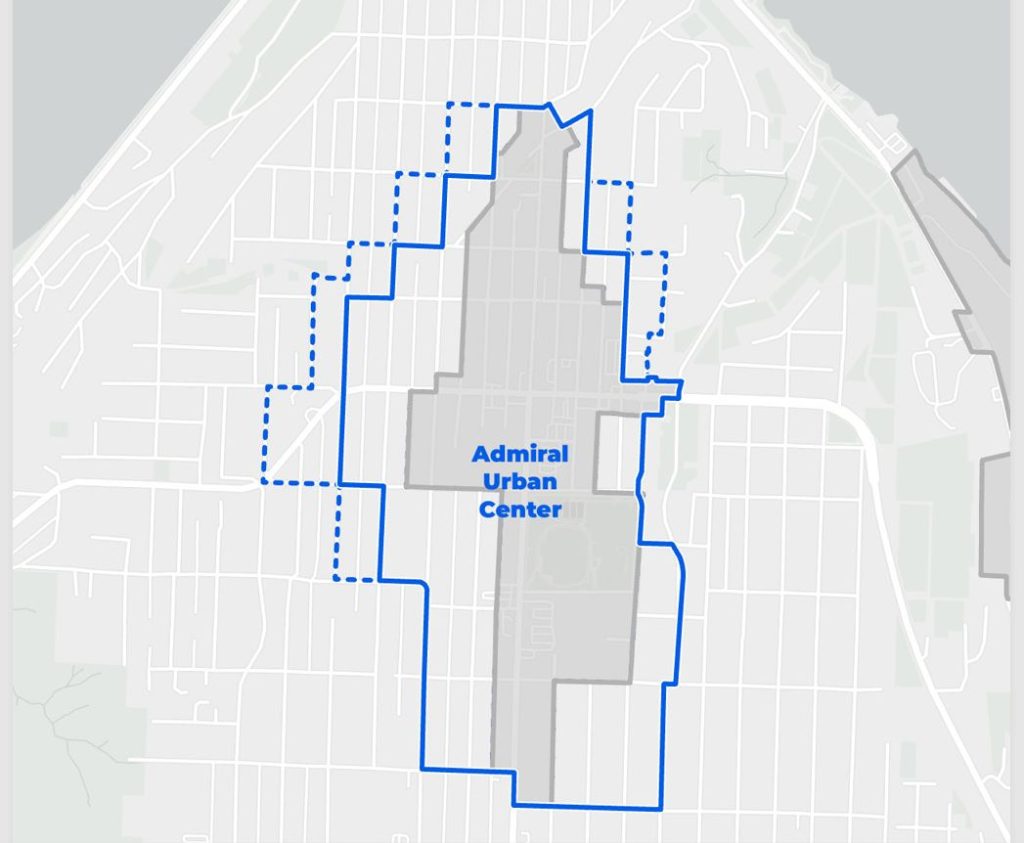

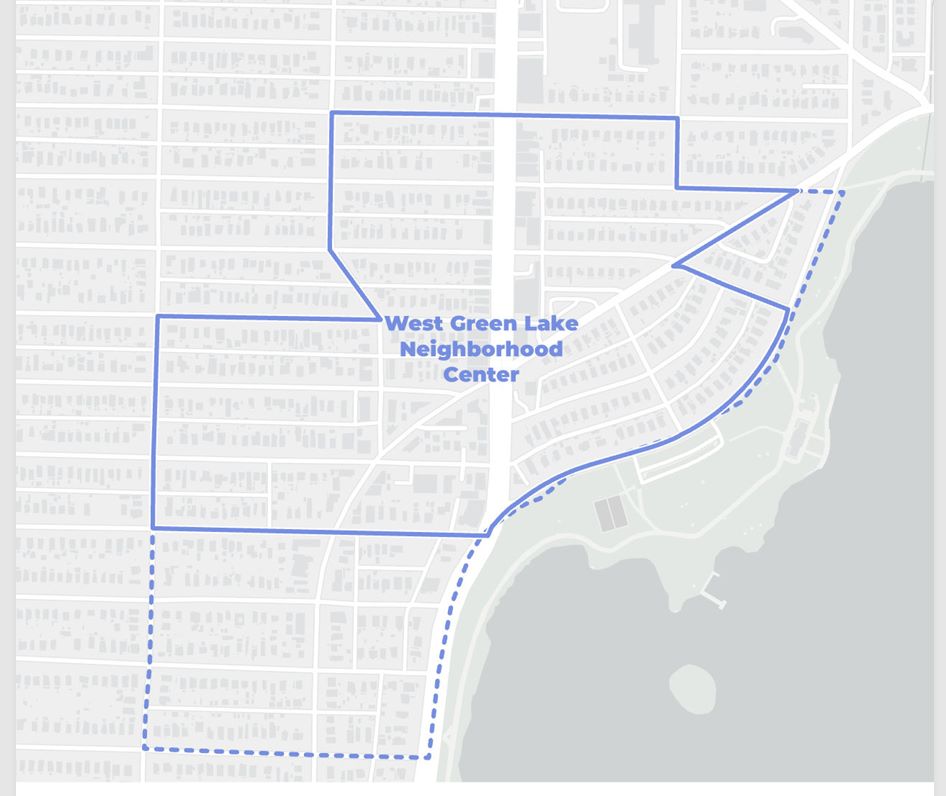

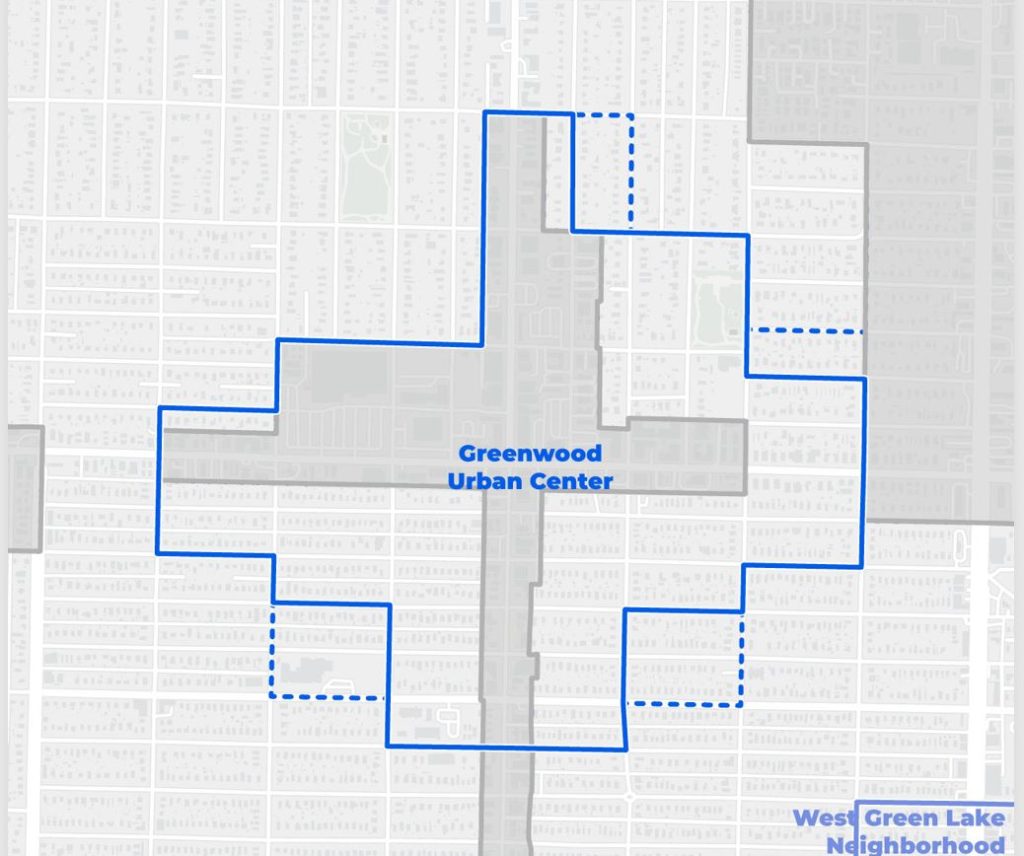

In urban centers like Queen Anne and Admiral, the areas proposed for expansion shrunk by around a dozen blocks, while most neighborhood centers saw a few blocks each dropped. Those neighborhood centers were already quite limited, with the full extent of most no longer than a couple blocks in any direction. OPCD had initially studied many more neighborhood centers in other areas of the city before ending up at the total number of 30, after some pushback from within the Harrell Administration.

“They don’t jump off the map because the boundary changes are very small, in the grand scheme of things,” Hubner said. “I don’t have an exact number of acres or percent change, but I would characterize it as a relatively minor reduction in the size of our expansions and in our new neighborhood centers.”

Hubner explained the approach OPCD took in pulling back neighborhood center boundaries, based on public comment that had been submitted to the city during last fall’s comment period.

“After releasing the mayor’s plan, there were some comments that pointed to and highlighted facts on the ground,” Hubner said. “They included things like environmental factors — mainly slopes — major concentrations of historic resources, infrastructure constraints, very, very narrow roadways or underground infrastructure that is a barrier to development, and access to transit and amenities — basically the quality and level of service of the transit, the distance to get to the transit and the distance to get to commercial districts, goods and services, locally.”

But several of Seattle’s planning commissioners expressed concerns about both the reductions themselves and the methodology that the city used to make them. Throughout 2024, the commission had been pushing for neighborhood centers to be bigger and more plentiful, and for the city to expand the areas along frequent transit routes where larger apartment buildings could be allowed.

“I would just point out that if you look at the location of where these reduced neighborhood center zones are, some of these are in areas where you don’t have a lot of other multifamily housing, you don’t have urban villages,” Commissioner McCaela Daffern said. “And if we’re truly going to buy into this vision, that everybody should have a choice to live in any neighborhood in Seattle of their choice, and that there’s abundant housing options there for everybody, neighborhood centers is a place to start, and it’s disappointing to me that we as a city through this Comprehensive Plan — while it still is a dramatic change from where we’ve been in the past — it’s still largely upholding our patterns of single family zoning, with some middle housing allowed within there.”

Daffern argued the move sent the wrong signal.

“I know you called it nominal, but from a values perspective, a [single] block is an important signal to those of us who are trying to open up the city to more people that you were still trying to push ourselves in that direction,” Daffern continued.

Commissioners questioned the criteria used to make the cuts, and the lack of effort to replaced the lost capacity.

“I also want to echo disappointment that when the boundaries were being adjusted, it would have been nice to say, okay, if you’re going to shrink, how about we expand elsewhere to keep the overall size the same, at least,” Commissioner Rose Lew Tsai-Le Whitson said. “I have frustration with lumping geologic hazard areas in with other more irreplaceable critical areas, like wetlands and streams. They’re different types of critical areas. You treat them differently. You mitigate them differently. And by and large, what I hear from my peers in the engineering realm is that a lot of geologic hazards can be mitigated for and could be buildable. So it’s frustrating to me to just blanketly say this is going to exclude the buildable area.”

Cecelia Black, a community organizer with Disability Rights Washington by day, also lifted up the impacts of reducing potential areas of neighborhood centers due to steeper slopes. Black raised similar points in an op-ed in The Urbanist.

“The more density we have throughout neighborhoods, the more accessible they are for everyone,” Black said. “Rather than assuming that these areas Seattle have a ton of slopes and steep hills, and assuming that they just can’t be accessible for people […] actually adding density into those hills make[s] them much more accessible because people aren’t having to go as far to access things that they need.”

Some city councilmembers, on the other hand, have questioned Hubner and staff from the Mayor’s Office why the reductions in the proposed scope of neighborhood centers weren’t more dramatic. Earlier this month, District 5 Councilmember Cathy Moore pressed on the fact that the proposed neighborhood center in North Seattle’s Maple Leaf neighborhood was left untouched, after a petition of several hundred people had demanded that it be wiped from the map.

“I did ask twice, before all of this came down, specifically requested that it not be designated a neighborhood center, and both times those requests were denied,” Moore said, suggesting that the treatment Maple Leaf had received was either due to a personal grudge against her personally, or because the area is less wealthy than neighborhoods like Madison Park and Magnolia. “I really remain dismayed at the unwillingness of OPCD to at least reach out to my office to at least offer to walk the neighborhood center to consider the legitimate concerns of that neighborhood group.”

“It’s not that we haven’t been listening. We’ve just arrived at a different conclusion,” Harrell’s Deputy Director of Policy, Christa Valles, said in response to Moore’s long speech. “I just want to stress that we’ve done the best we can to develop a plan that balances the range of interests across the city.”

Moore won’t be around for a final vote on the Comprehensive Plan, after announcing her resignation effective July 7. A new D5 councilmember appointed by a majority of the eight remaining councilmembers will take office by the end of July.

In the same meeting, District 4 Councilmember Maritza Rivera didn’t press as hard as Moore, but still suggested that the City hadn’t fully done its due diligence to examine potential neighborhood centers, citing the contentious Bryant center near the Metropolitan Market on NE 55th Street.

“I know there is a bus line there, but it is a very tight space in that proposed neighborhood center,” Rivera said.

Despite those interrogations of OPCD staff, the fate of the neighborhood centers now rests with the council, which is expected to take a vote on the final boundaries for the centers this September, before updating the actual zoning inside those centers next year.

This upcoming Monday, the council will hold an all-day public hearing on the entire One Seattle Plan, with phone comments accepted starting at 9:30am and in-person comments accepted starting at 3:30pm. Those in-person commenters must sign up by 6:30pm to be able to testify.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.