A paper trail shows Mayor Harrell’s office cut transit corridor upzones and half the proposed “neighborhood centers” before release of Seattle’s growth plan.

Seattle is in the midst of charting its growth strategy for the next two decades. Mayor Bruce Harrell’s draft Comprehensive Plan, released in March, was greeted with disappointment, as housing advocates called for bigger changes and more housing opportunities across the city. Documents recently obtained by The Urbanist through a public records request show that the Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) had proposed a more ambitious option last fall before the department was overruled by the Mayor’s Office.

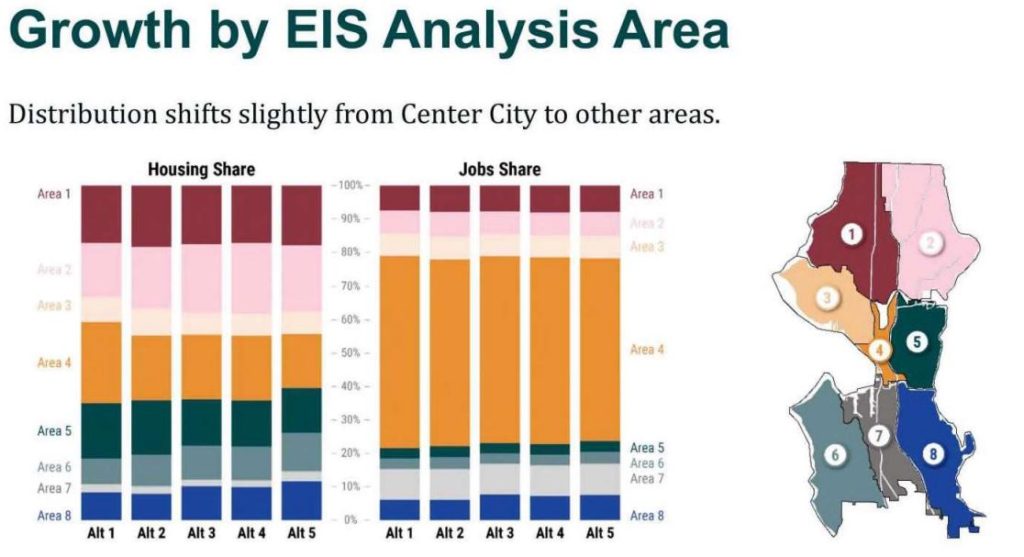

The scoping report that OPCD put out in late 2022 had considered an alternative that modified zoning to allow five-story apartment buildings near frequent transit corridors, affecting areas where currently only single-family homes or low-rise developments are allowed. That “Corridors” approach was also included in the Combined Alternative 5 from the report, which was the most popular of the City’s options in public comment, but it disappeared from the Mayor’s proposal.

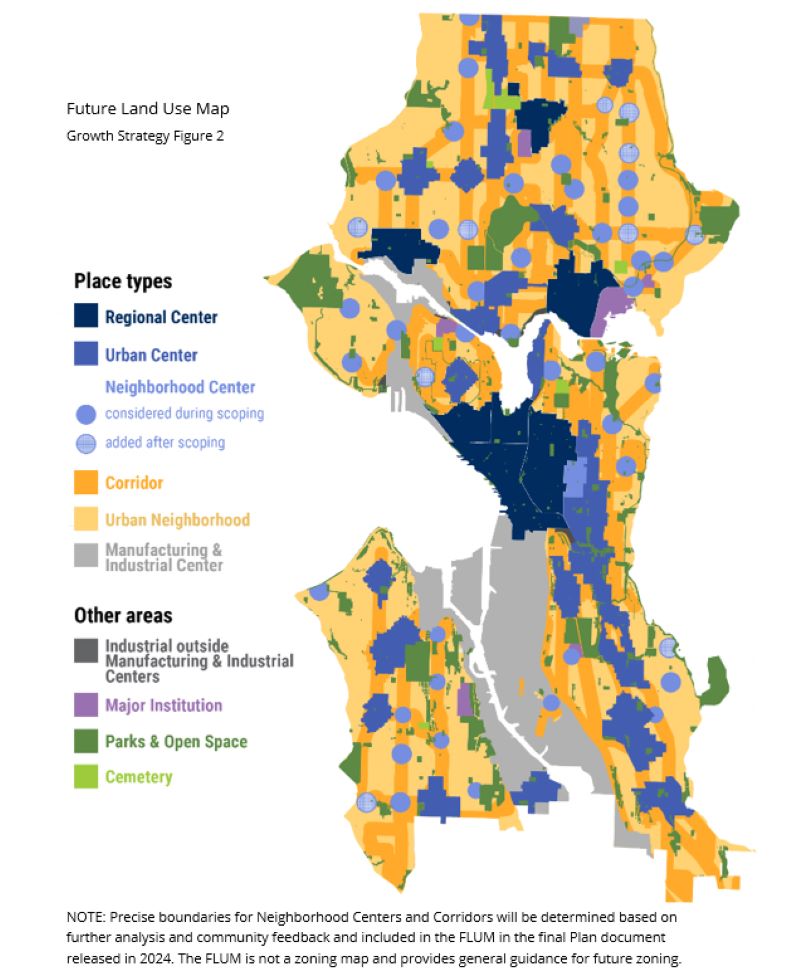

Insofar as it diverges from the status quo, Harrell’s growth strategy leans heavily on “Neighborhood Centers,” which had been called “Neighborhood Anchors” in the scoping report and had been considered as an option going back to the original formation of the “Urban Village” growth strategy in the 1990s. Basically, these centers are Urban Villages in miniature, with zoning changes for four- to six-story apartment buildings extending “about 800 feet” from the nucleus of a local business district.

Even with the “Neighborhood Centers” being a focal point of the Mayor’s strategy, their number was essentially cut in half from the proposal that the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) was working on over the summer of 2023 and submitted to the Mayor’s Office for review in September (see the map above). While OPCD’s fall draft included almost 50 Neighborhood Centers, the Mayor’s March proposal pared back the quantity to just 24.

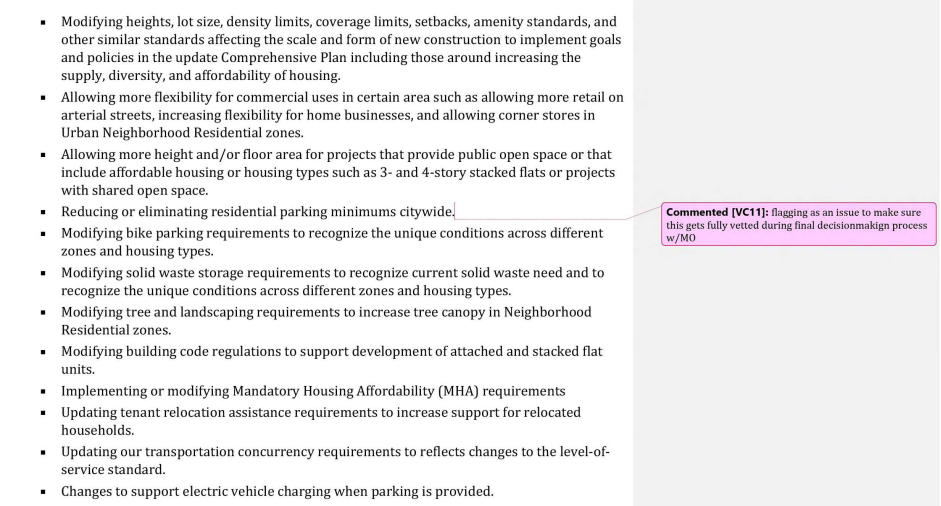

Moreover, OPCD’s draft Comprehensive Plan policy updates proposed “reducing or eliminating residential parking minimums” citywide, building on a more targeted parking reform passed in 2018 with then-Councilmember Harrell voting in favor. However, this fall a staffer flagged the issue in the draft and the Mayor’s final draft did not make them the same policy pledge, while not quite closing the door on the idea either.

Housing advocates push for more apartment zoning

Under the banner of the Complete Communities Coalition, a broad cross section of nonprofit advocacy groups, business groups, and labor has pushed the City to pursue broader upzones. The coalition includes Futurewise, Housing Development Consortium, the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, House Our Neighbors, and The Urbanist, among others. [The Urbanist’s advocacy staff and volunteers participate in coalitions independently of our editorial team.]

Tiernan Martin, who is research director with Futurewise, expressed a preference for the earlier combined strategy proposed by OPCD.

“Futurewise was disappointed to learn that the Mayor’s Office, when presented with a plan to disrupt Seattle’s well-documented pattern of racial and economic exclusion, instead recommended a growth strategy that will reinforce these inequities,” Martin said.

Following release of the Mayor’s proposal, the Complete Communities Coalition has released recommendations some of which clearly steer the City back toward OPCD’s original strategy. “Allow for midrise housing in all areas served by frequent transit, in the quarter-mile around frequent bus service and half-mile around light rail,” one recommendation reads. “Reintroduce Neighborhood Centers that were studied but not included in the Draft Plan,” another reads, with the additional suggestion of extending the changes to a quarter-mile radius rather than just 800 feet.

The Mayor’s Office disputed criticisms of the final plan and argued their proposal aligns with the values of racial equity and housing abundance.

“The Mayor’s plan is consistent with the values he expressed prior to taking office, rooted in a commitment to urgently support the ability to build more housing throughout Seattle in a thoughtful manner and mitigate displacement risks to historically marginalized communities,” the Mayor’s spokesperson Callie Craighead said in a written statement.

Reading between the lines, it appears the Mayor shifted away the “Corridor” alternative, which had been aimed at adding midrise apartments in transit corridors, in part due to a preference for owner-occupied homes (e.g., townhomes) rather than apartments.

“The direction from Mayor Harrell and the Mayor’s Office for the One Seattle Plan was to increase the abundance and diversity of housing in every neighborhood to meet urgent housing needs and prepare for future growth,” Craighead said. “To that end, the draft adds new housing capacity and density in all neighborhoods, capacity for middle housing in historically single-family areas, and capacity for many more apartments and condominiums along transit corridors and in an expanded network of regional, urban, and neighborhood centers. It balances the need for more homeownership opportunities while encouraging more density in walkable, high service communities.”

Records also show OPCD making the case that it would be wise for Seattle to pursue the transit corridor approach to promote housing abundance and affordability and to get ahead of a potential state mandate that lawmakers have been considering the last two sessions. “OPCD is proposing an expansion of TOD in the city because we think it is good policy to better meet our housing, transportation, and climate goals,” one slide bulletpoint read, apparently in preparation of winning over skeptics in the Mayor’s Office.

However, the argument did not win the day and the failure of the transit-oriented development bill to clear both state legislative chambers thus far seems to have convinced the Harrell Administration to wait and see rather than forge ahead.

It wasn’t just OPCD’s outreach during scoping that found support for aggressively adding more housing; a recent poll commissioned by the Seattle Chamber of Commerce found a spike in housing cost concerns and in popularity for housing development among Seattle residents. The twice-annual poll found a five-point jump in favorability ratings for local “growth and development,” and 69% agreed with the statement that “I support the building of a wider variety of housing in my neighborhood.”

Harrell team defends their cuts

Craighead provided a framework that was allegedly used by the Mayor’s team to select the 24 Neighborhood Centers from the roughly 50 proposed by OPCD, but it is not clear how closely it aligns with how the decisions were actually made. Some cuts did not align with the specified criteria. Access to frequent transit, access to shops and services, geographic coverage (i.e., “creating opportunities for apartments in areas that currently have few apartment units”), and areas with lower risk of displacement were the factors the Mayor’s team used, Craighead said.

However, the sheer amount of neighborhood center cuts in North Seattle — generally where displacement risk is very low, amenities are high, and apartments are less concentrated — suggest that other factors beyond those espoused were at play. For example, OPCD’s draft had 14 Neighborhood Centers in Northeast Seattle, a quadrant of the city noted for its lack of urban centers and for being a predominantly White and wealthy area, but Mayor Harrell proposed just six.

Two Neighborhood Centers on the edges of wealthy Queen Anne, two more in Laurelhurst, and two others in Broadview disappeared after the Mayor’s Office intervened, as well one in northern Magnolia, South Wallingford, Upper Fremont, West Woodland, to name a few. All of these areas of high opportunity and low displacement risk. Transit frequencies varies across these fledgling commercial districts, but in some, such as Laurelhurst and Broadview, service is quite good.

And of course, a concerted effort from the City of Seattle and its partner King County Metro could certainly improve transit frequencies where they are lacking rather than accepting mediocrity as a given.

Some possible openness to additions

The Mayor’s Office did indicate some openness to adding more Neighborhood Centers, in addition to funneling more growth into the City’s existing growth centers.

“We anticipate reviewing the number and location of these neighborhood centers in the context of the public feedback we receive,” Craighead said. “It is worth emphasizing that OPCD still needs to create subarea plans for each of the seven regional centers. The Mayor’s Office is encouraging OPCD to look for additional upzoning opportunities as part of this work. Moreover, the Mayor is also interested in further upzoning near high-capacity transit stops and in existing urban centers. We anticipate a great deal of additional zoning capacity could result from these moves.”

Last week, Seattle City Councilmembers Rob Saka and Tanya Woo, at a meeting of the 34th District Democrats, criticized the plan released by the Harrell Administration as being not ambitious enough, the first time they have publicly aligned themselves with land use chair Tammy Morales, who has been forthcoming in her criticism of the plan.

Woo referenced feedback she has been receiving at the One Seattle Plan open houses in districts all around the city. “Yes, that’s what I’m hearing at [the open houses]: that we need to build more housing, we need a more ambitious plan,” Woo said. “And so I really do hope that you submit your comments, and hopefully the Mayor will hear them and change his plan but we won’t see it [at council] until later this year.”

Risk of missing state deadlines and requirements

The record of correspondences between planners at OPCD and officials in Mayor Harrell’s office show that OPCD’s draft was transmitted to the Mayor’s Office ahead of the September release that the department had pledged following the plan’s first delay in April 2023, but then the Mayor’s Deputy Policy Director Christa Valles raised a number of concerns on behalf of the Mayor both in emails and document comments. Valles questioned both technical details and modeling and the broad idea of going beyond state minimum requirements.

In hopes of hashing out their differences, OPCD held a number of meetings with the Mayor’s policy team (which seemed to consist of Valles, Policy Director Dan Eder, and Chief Operating Officer Marco Lowe) in the fall. However, coming to agreement took some time and OPCD preceded to delay the draft plan’s release, declining to give a firm timeline until it finally released the plan in March.

Internal OPCD documents suggest that the department over the summer of 2023 was already anticipating not finalizing zoning in 2024 even as it was holding out hope of finalizing the Comprehensive Plan itself in that timeframe, pushing zoning changes close to the hard deadline of June 30, 2025 imposed by the state via Representative Jessica Bateman’s HB 1110 middle housing legislation. The Mayor’s Office delaying release of the draft plan from fall 2023 to spring 2024 suggests that meeting that state deadline will be difficult, as The Urbanist warned as the delays were happening.

The Harrell Administration had blamed initial Comprehensive Plan delays on needing to comply with new state law, with the middle housing mandate coming into force during the 2023 session. While state legislation had intended to set a floor and encourage jurisdictions to think bigger about their housing growth strategies, it appears in the case of Seattle that the state thresholds in some ways became a ceiling, with some officials wanting to go only as far as House Bill 1110 was requiring them to go.

In fact, Rep. Bateman has contended that the Seattle’s draft plan would fail to comply with her legislation in part because the restrictions on fourplexes and sixplexes are too onerous, particularly with respect to floor area ratio regulations that cap the size of homes significantly in comparison with the single-family homes they’d be replacing.

Likewise, the growth targets set by King County has had a similar effect with some questioning why Seattle should strive higher than the 112,000-unit 20-year growth target that the County set for them. For example, Valles asked OPCD if only applying HB 1110 would be sufficient to meet the Growth Management Act requirements.

“While we cannot predict how much housing will actually get built in the coming decades (which is dependent on a number of factors, zoning capacity being only one of them), we expect to have more than enough zoned capacity to accommodate any proffered supply,” Craighead said. “And while we can’t state an exact number until the zoning work is done, we estimate that zoned capacity will well exceed 200,000 units.”

While it is well understood among planning and development professionals that not every parcel with added zoning capacity will redevelop, especially on only a 20-year timescale, it appears that the Harrell Administration may be comfortable with living fairly close to the edge of housing constraint. As long as capacity for at least 200,000 new homes exist on paper, why fret? But people can’t live in homes that only exist on paper.

Comment on the plan

Through May 20 at 5pm, OPCD is accepting public comment on the Comprehensive Plan via the online Engagement Hub, by email, or by attending upcoming public meetings:

- Tuesday, April 16 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm

Garfield Community Center, 2323 E Cherry St, Seattle, WA 98122 - Thursday, April 25 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm

Eckstein Middle School, 3003 NE 75th St, Seattle, WA 98115 - Tuesday, April 30 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm –

McClure Middle School, 1915 1st Avenue W, Seattle, WA 98119 - Thursday, May 2 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm

Virtual Online Meeting, link to be provided at a future date

Update: OPCD’s comment period was extended by two weeks and this piece has been updated accordingly.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.