Builders and advocates warn proposal is “nothingburger” that will come up short on affordability, livability, and complying with state law.

On Tuesday, City officials rolled out their “One Seattle” Comprehensive Plan draft proposal after a series of delays that stretched back to the original April 2023 release date. Housing advocates were not thrilled with what was revealed, worrying that Seattle’s general trajectory toward a worsening housing affordability crisis was not being altered.

The Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) cited new state legislation as a major reason for the delay of almost one full year in releasing the draft plan. In April 2023, the state legislature passed House Bill 1110, which established a new mandate for major cities to allow fourplexes in areas currently zoned exclusively for single-family homes in their next comprehensive plan. The mandate rises to sixplex zoning near frequent transit or if two of six homes are set aside as affordable. Lead sponsor Rep. Jessica Bateman (D-22, Olympia) crafted HB 1110 to ease the housing crisis, but she said Seattle’s proposal would fail to comply with the spirit of the law.

“It’s really disappointing to see the largest city in the state go through so much public engagement that they have to come up with their plan for how they’re going to accommodate housing and to have it be so underwhelming,” Bateman told The Urbanist in an interview.

Rep. Julia Reed (D-36, Seattle) echoed that sentiment, saying she was “pretty disappointed” in the plan in a tweet on Tuesday. “The largest city in the state should be maximizing the use of the tools [the Washington State Legislature] is providing them, not doing the minimum,” she said.

Pretty disappointed with what I'm seeing so far in the @CityofSeattle comprehensive plan and expressing those concerns to City reps. The largest city in the state should be maximizing the use of the tools #waleg is providing them, not doing the minimum. https://t.co/58uutK83K3

— Rep Julia Reed (@RepJuliaReed) March 5, 2024

David Kroman of The Seattle Times also picked up the story of disappointment from Bateman and other housing advocates in a story Wednesday. “I don’t think it goes far enough to enable the actual construction of housing,” Bateman told The Seattle Times.

The Harrell administration has mostly cut larger zoning changes near transit lines from the plan, despite an earlier option that would do just that — Alternative 4. The state legislature had also considered a mandate for larger zoning changes near frequent transit, but that bill ultimately fizzled both this session and last session. And while the City of Seattle proposes allowing fourplexes, it is not actually increasing the size of the development that is allowed on a lot, which will translate into smaller homes or a lack of builder interest.

Architect and Seattle Planning Commissioner Matt Hutchins was among the critics of the mayor’s proposal. “This comp plan will goose townhouse production, but it doesn’t fulfill the spirit of HB 1110 or get at the underlying challenges around housing affordability and climate here in Seattle,” he tweeted.

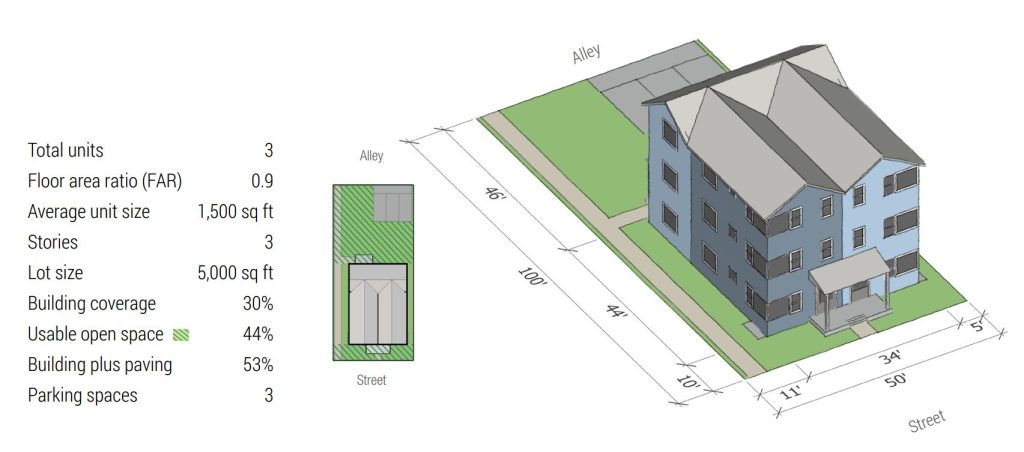

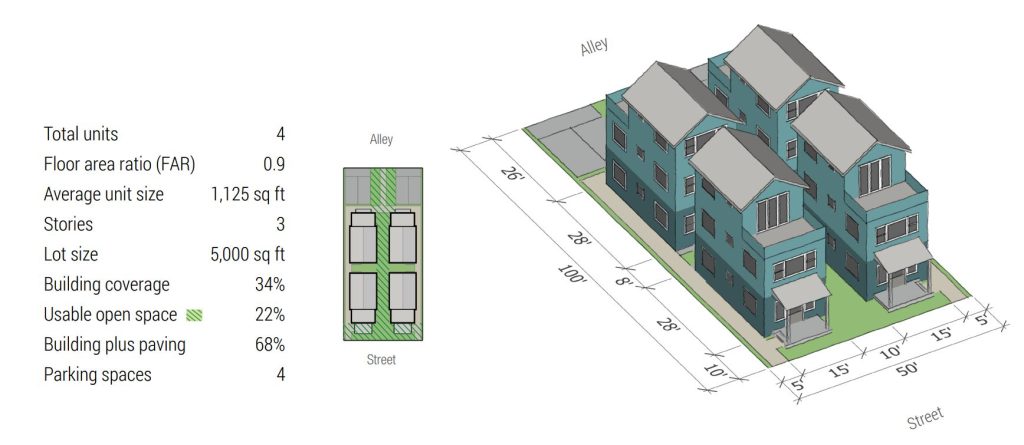

A typical 5,000 square foot lot would be capped at 4,500 square feet of housing due to a proposed floor area ratio (FAR) maximum of 0.9. That means each townhome would be about 1,100 square feet. Considering that stairways eat up some of that area on each level, that could be tight for a family of four, let alone larger families. Nonetheless, Hutchins said such a townhome is still likely to sell for $750,000 in most Seattle neighborhoods. In other words, we aren’t changing the fundamental calculus enough to impact affordability in a big way.

The other problem with tight building size restrictions is that smaller lots may only support a triplex or duplex instead of a fourplex. That’s yet more homes off the table in the midst of a housing crisis.

Bateman also cast doubt on whether this complied with her bill.

“One of the provisions within 1110 said that you can’t have development regulations that are more restrictive than for single-family homes,” Bateman said. “And I have a question about the 0.9 FAR, and if by making fourplexes, and sixplexes not feasible to construct with all of the other minimum lot size requirements, etc., that that could be interpreted as being more restrictive than what is allowed for single-family housing.”

Bateman also said that OPCD had incorrectly interpreted the provision allowing cities to exempt up to 25% of single-family zones from HB 1110’s missing middle provisions.

“They’re including the displacement [delayed implementation provision] in that; they can do that, but what they can’t do is they can’t say that the displacement areas are off-limits indefinitely,” Bateman said. “That is not the intent of the legislation. That’s not what the bill says. They’re interpreting it that way, and we need to have a discussion about that.”

Seattle taking a bare minimum approach also sets a bad precedent and model for other cities, lawmakers worried.

“It’s not meeting the mark of where they need to go,” Bateman said. “I also know that other cities are looking to Seattle to see what they do. So the model that they provide will be a model that is taken notice by so many other cities. And so that’s why, in addition to them being the largest city in the state, the big job growth convener in the state, they really need to aim higher. They need to be looking much more forward and challenging themselves. So they can be the livable, walkable, amazing city that they need to be.”

While OPCD is projecting a modest uptick in townhome production, the bulk of Seattle’s growth strategy will remain focused in the same core neighborhoods — “Regional Centers” and neighborhoods formerly called “Urban Villages” and now rebranded “Urban Centers.” The townhome zones in between those centers would see just 8,800 additional homes out of 120,000 units according to OPCD’s 20-year projections for the Combined Alternative 5 released along with the plan’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement today. That’s just 7% of the growth projected over that span. While the mayor’s growth plan is different than Alternative 5, a spokesperson said it is the most similar of the five to his mix-and-match approach.

“So it’s essentially just kind of a big nothingburger around what’s happening with the Urban Villages,” Hutchins told The Urbanist. “We just expect the current Urban Villages to continue to produce […] two-thirds to four-fifths of our housing, whatever they’re called.”

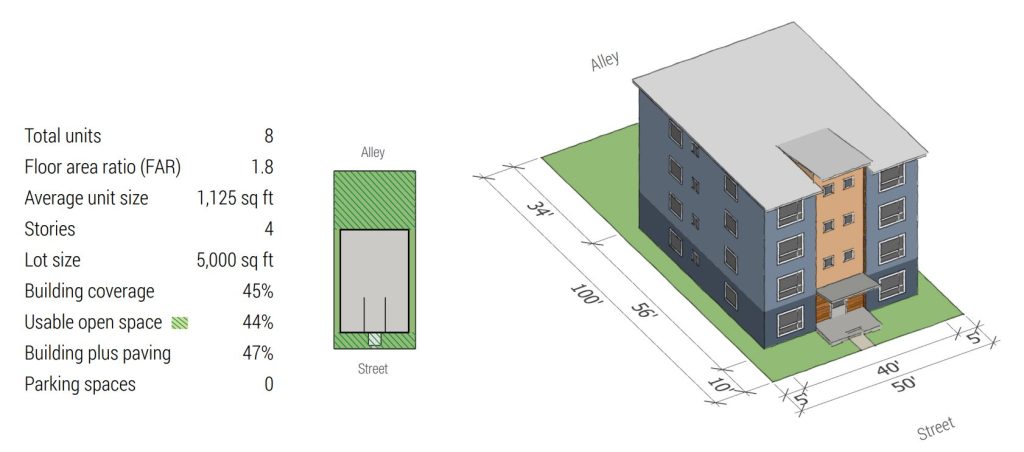

Hutchins has been vocal about how sixplex stacked flats can be more livable than skinny townhomes packed onto tight lots and the economic feasibility could be better too. In addition to fostering better outcomes, Hutchins has also argued sixplexes are easier to justify on the typical single-family lot since homebuilders need to be able to build enough homes to justify tearing down a single-family home that would likely sell for more than $1 million, especially after remodeling.

“We just need to be able to squeeze a lot more units out of every parcel that gets redeveloped,” Hutchins said. “It’s a generational investment. And we don’t have a lot of opportunity to like really effect this. So, yeah, so six, eight, ten [homes per lot]. That’s, that’s where you start to get to where it’s feasible, given Seattle’s land costs, construction costs, soft costs, all the costs, and that’s where it makes the biggest impact and the biggest benefit.”

This is what planners want. This is what the Mayor wants.

— Matt Hutchins (@HutchinsMatt) March 6, 2024

As urban design, this is just sad for Seattle-no yard, no trees, no place to play, no place for aging or the disabled, all but 3 rooms look directly at neighbors, lowest energy/material efficiency, but for sale-fee simple pic.twitter.com/MEckZqivTS

Hutchins had also criticized an early draft model code from the state Commerce department, which would become the default for cities that fail to adopt their own version of House Bill 1110 reforms. The chorus of criticism from Hutchins and others pushed Commerce to revise its model code to be less restrictive. As The Urbanist‘s Stephen Fesler reported, “Maximum floor area ratio was tailored to unit counts and adjusted upward with 0.6 for one unit, 0.8 for two units, 1.0 for three units, 1.2 for four units, 1.4 for five units, and 1.6 for six units.”

In other words, with their 1.2 FAR for fourplexes, the state recommends 33% larger homes than Seattle. The state’s 1.6 FAR for sixplexes would translate into homes that are almost 80% larger than under a 0.9 FAR. On a 5,000-square-foot lot, the sixplex FAR limits would cap homes at 1,333 square feet each under the state’s zoning or 750 square feet each under the One Seattle plan. That’s pretty small for a multi-bedroom home.

With such a low FAR cap, OPCD seems to concede that developers may actually gravitate toward triplexes (or just adding the two accessory dwelling units already allowed under existing zoning). A triplex could manage 1,500 square feet per unit on a 5,000-square-foot lot. The problem with triplexes, though, is that the collective value is not much higher than a large oneplex, which decreases the likelihood a site would be redeveloped at all. Is it worth the hassle?

Hope that nonprofits would pick up the slack could also be illusory, some homebuilders have said. Ben Maritz, who runs the Great Expectations development firm (and also serves on The Urbanist’s board of directors) warned of the lack of funding streams for small nonprofit projects.

“We should be clear: the ‘affordable’ 8-plex is not a thing. There are no scaleable funding sources for such a tiny project, and given the overhead associated with any subsidized project there never will be,” Maritz said Wednesday in a tweet.

Another downside of Seattle going all in on townhomes is that once a lot is subdivided and redeveloped as townhomes, it becomes nearly impossible to redevelop the lot as anything else. The lots gets diced into tiny 1,250-square-foot pieces too small to support other uses. Ray Dubicki stressed this point back in 2020, but townhomes continue to be the City of Seattle’s main plan to redevelop most of its residential land. Widespread townhome development could provide a minor salve for today, but a headache to untangle down the road that traps land in a lower density use.

The end result of a plan that does not plan for enough housing is that Seattle’s affordability crisis will continue to linger. But it’s not too late to change that. The One Seattle plan’s public comment period continues through May 6 both online and a series of open houses around the city.

- Thursday, March 14, 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. Loyal Heights Community Center

- Monday, March 19, 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. Cleveland High School

- Monday, March 26, 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. Nathan Hale High School

- Wednesday, April 3, 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. Chief Sealth International High School

- Tuesday, April 16, 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. Garfield High School

- Thursday, April 25, 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. Eckstein Middle School

- Tuesday, April 30, 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. City Hall, Bertha Knight Landes Room

- Thursday, May 2, 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. Virtual Online Meeting, link to be provided at a future date

Ryan Packer contributed to this story.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.