Is Everett’s plan to move the AquaSox from aging Funko Stadium to a brand new downtown stadium an economic jolt or a costly gamble?

Since 1947, Everett’s Funko Stadium has held everything from AquaSox games to grade school baseball games – but times are changing. The AquaSox are the High-A minor league affiliate of the Seattle Mariners and due to pressure from Major League Baseball to upgrade minor league facilities, AquaSox ownership says now it’s time for a stadium revamp. The league’s new amenity requirements include larger locker rooms, umpire accommodations, more parking, and enhanced seating. The 3,682-seat Funko Field does not meet these standards.

The city had three options: renovate, build a new stadium, or do nothing.

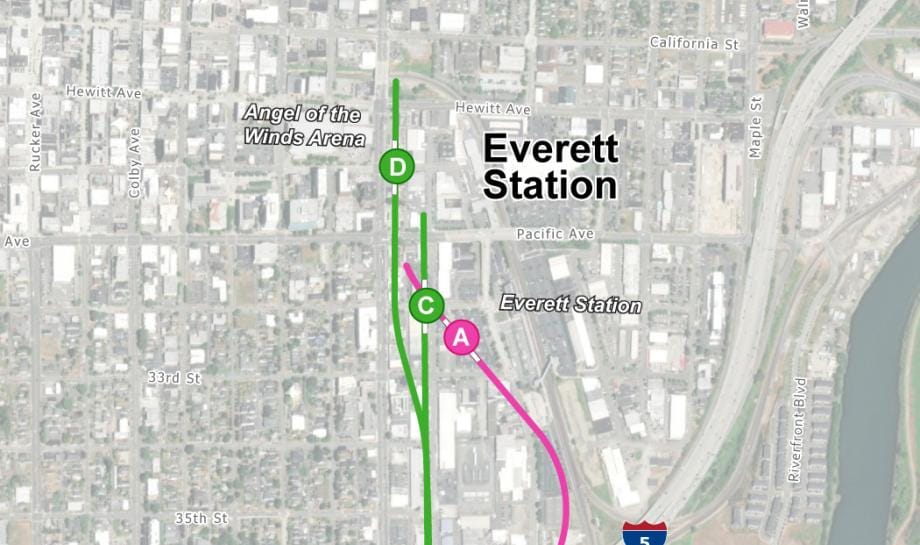

Everett chose the second option. On the eve of the new year, December 2024, the Everett City Council unanimously chose a site east of Angel of the Winds Arena — at the corner of Broadway and Pacific, right next to the Sounder rail line.

As of June 2025, the project is in full swing and hoping to break ground in early 2026. The city is planning to tap Bayley Construction to build the new stadium.

“The Outdoor Event Center is a key piece of our plan to grow Everett the right way – with more housing, better access to transit and a more vibrant, walkable downtown. It’s about bringing people together, creating new opportunities and growing our local economy to support the quality of life and robust public services our residents deserve,” Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin said.

The City plans on spending $4.8 million to advance the (OEC) Outdoor Event Center stadium project to the shovel-ready stage. The City forecasts contributing a total of about $8 million toward construction and has budgeted an additional $20 million to acquire 15 properties needed to clear room for the facility. It’s likely some business relocation assistance and possible eminent domain will be needed, the City said.

Some opponents of the new stadium are using a “No Frogs Downtown” slogan, referring to the AquaSox mascot. Legend says iconic mascot Weebly is a cross between a Pacific Tree Frog and a Central American red eyed tree frog. In a port town that can be soggy and gray, the logo is a nod to Everett’s amphibious identity.

Proponents argue the city risks losing the AquaSox team to another city with a newer stadium if they do not build the new stadium. And the transit-rich location helps Mariners fans from across the region see prospects play before they reach the big leagues. Fans can also see the franchise’s more advanced minor leaguers at Triple A team Tacoma Rainiers, the last stop before the majors.

With a price tag projected at $82 million or more, will the benefits of a brand new stadium outweigh the costs and how does the public feel about the project? And is it the best use of the land chosen, among the most transit rich areas of downtown Everett?

City promises revitalization and year-round activation

The Franklin administration is all in on the stadium.

“At its core, this is an economic development project. Losing the AquaSox would have a negative economic impact on our community. A new facility downtown that can host baseball, soccer, concerts and other events, plus include a public park, has significant positive benefits – not just economically but also for the quality of life of our residents.” said Simone Tarver, spokesperson for the City of Everett.

For the City of Everett, this is more than a passion project; it’s been their mission for the last several years. “It’s what we think about when we wake up,” said Dan Eernissee, economic development director at the City of Everett.

To its backers, the proposed ballpark would be an investment in the future, contributing to downtown revitalization. The City is also hoping to use the new stadium to attract a minor-level pro soccer team, potentially both men’s and women’s. “The United Soccer League already is intending to be a big part of the project,” Tarver said.

Everett council envisions over 100 days of annual use, including concerts, soccer matches, and festivals.

“106 outdoor events will dovetail well year-round,” Eernissee said. He added that the stadium will serve as a public park and community space, potentially including a dog park on the edge of the property. “tThe OEC will most definitely have a park element” Tarver says, “As density increases so do people with dogs.”

“Do you know how many people in Everett have dogs?” Eernissee said. “50% of people in multifamily housing developments have a dog these days!”

For businesses near the proposed site — between Hewitt and Pacific Avenues — the stadium means potential foot traffic, tourism, and a new wave of investment.

“It’s going to make Everett an all seasonal destination,” Eernissee said. “Now these businesses can provide pizza all year round, like Broadway Pizza could even start seasonal specials.”

But where is the money coming from to fund such a venture?

Questions about cost, transparency, and displacement

The stadium’s projected cost — budgeted at $82 million — has raised eyebrows. Everett’s Stadium Fiscal Advisory Committee released a report that said the downtown site would be the “most fiscally beneficial option” in the long-run, despite greater upfront costs, pegged between $102 million to $133 million.

The funding for the new Everett stadium is set to come from a mix of public and private sources and use a public-private partnership model. The plan suggests transferring project delivery to a third-party non-profit facilitator and recommends using Public Facilities Group as that facilitator.

The City’s “target budget” projects a $82 million, but they admit that a full picture of costs will not emerge until the design is finalized. The higher earlier estimate could indicate costs will rise.

- $42 million for hard construction costs.

- $20 million for soft costs (e.g., design, permits, taxes, fees, and contingency).

- $20 million for property acquisition.

The City of Everett is committing around $7 million, potentially from capital improvement and park impact fees, while state and county support may include a $7.4 million infrastructure grant from Washington State and a $5 million contribution from Snohomish County. The AquaSox have pledged $10 million to the new stadium, and the City is hoping to secure $10 million from the United Soccer League.

“Until design is closer to complete, we won’t have the final cost. The most recent approvals from Council provided funding to get design to 60% at which point we will have a more complete picture of the costs to share with the Council as well as our community,” Tarver said.

To cover the majority of construction costs, it’s likely that the City will issue revenue-backed bonds, with repayment tied to stadium-generated income such as leases and ticket surcharges.

Eernissee says that the stadium is part of a larger marketing strategy for the future, while also trying to get ahead of the real estate bubble itself.

“This is likely an area where there will be a lot of market pressure to develop,” Eernissee said. “Before the market rates get too high we’re trying to get a high enough facility that it’s appropriate for an urban center.”

Transit complement or impediment?

The City contends that the new stadium aligns with Everett’s overall strategy of increasing public transport and development within the downtown area.

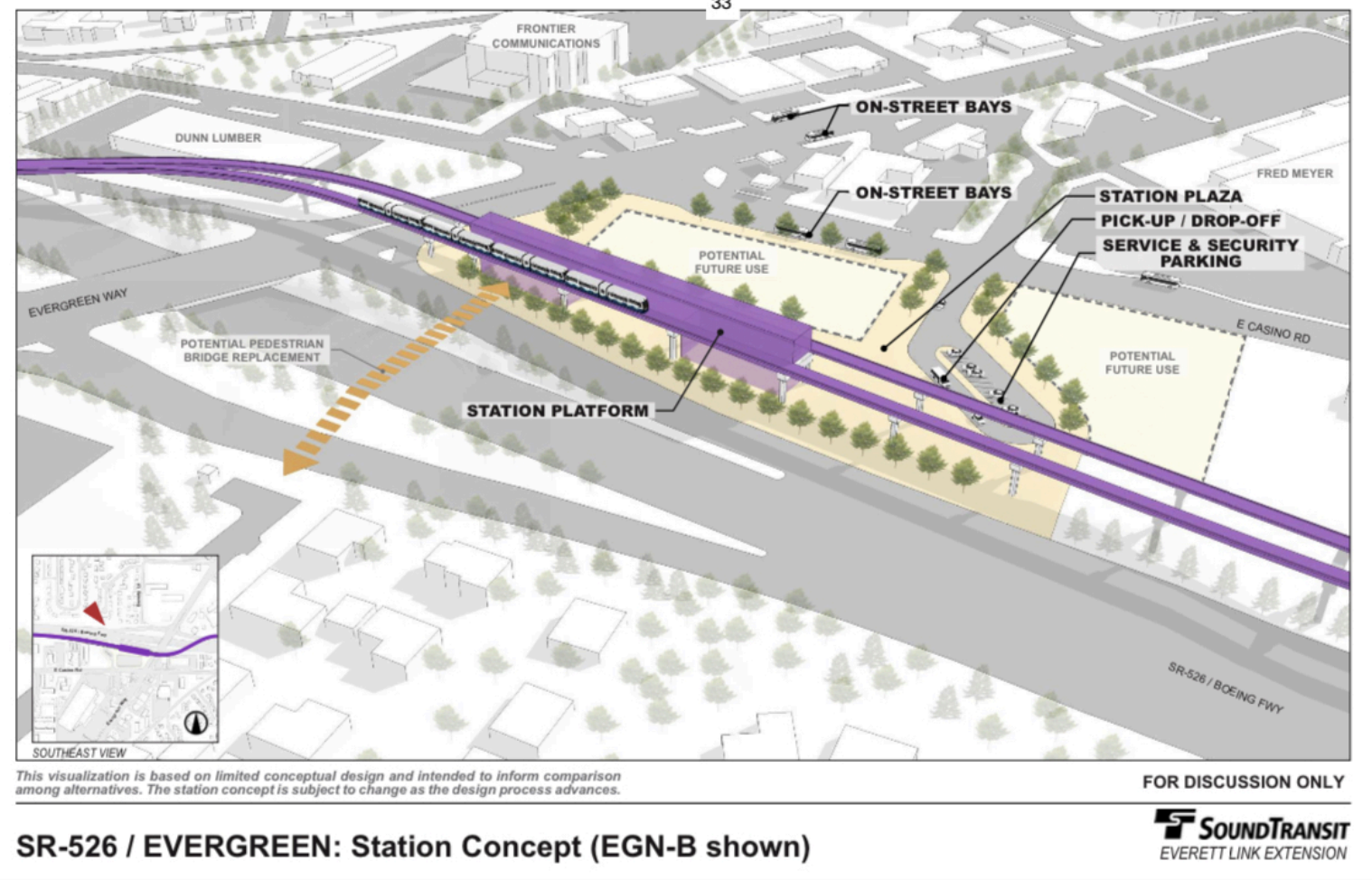

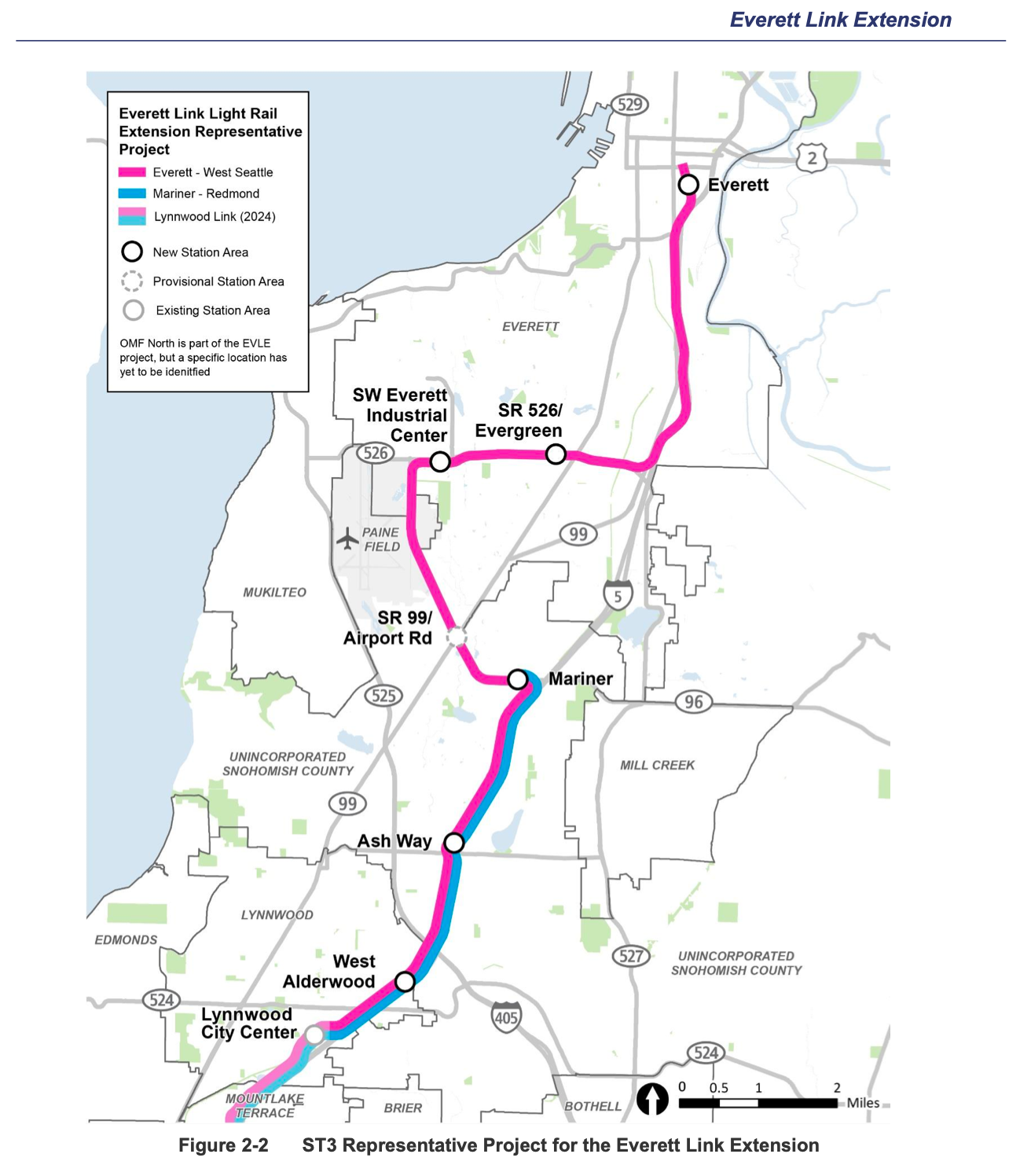

“Sound Transit will work hand in hand with our city team,” Tarver said. “We anticipate this area will be close to a light rail station in the future.”

And while the Everett Link extension isn’t expected until 2037 at the earliest (or 2041 if Sound Transit cost control and realignment efforts don’t go well), the city is already taking steps to prepare for it.

“We’re still in the planning phase, so those specific decisions haven’t been made yet. Right now we are in the middle of Everett Transit’s Long Range Plan online open house to solicit input from the community on how transit services should evolve between now and 2044. Public input is such an important part of that,” Tarver said.

Downtown Everett’s future light rail station is expected to be sited near the existing Sounder station, which would put the light rail stop in close proximity to the proposed stadium. Sound Transit’s preferred option is just west of the existing transit center, but Alternative D would overlap with the stadium site. If light rail is ever extended farther north, having two stadiums bookending Broadway could prove to be an obstacle for siting a path for the extension.

Transit boosters have argued that high-density housing should be the top priority within a short walk of light rail, given the huge investment the region is making and the incredible transit access those areas will have.

Everett upzoned its downtown core in 2018, allowing 25-story towers in some areas — though highrises have yet to materialize and Everett’s population has grown slowly compared to its peer cities in the region. The proposed stadium site is in that 25-story highrise zone with a buildable square footage of 3 million.

While the stadium would negate the site’s housing capacity, the City seems to be banking on the project being a catalyst to spur redevelopment elsewhere in the downtown core.

Property acquisition and displacement

The land the stadium is set to build upon is currently the site of some retail businesses, but most of the site is made up of older auto repair shops and specialty businesses.

Of the local businesses still operating there, most owners are actually in support of the plan, even if it means possible displacement.

“Stadiums are always good,” said John, a cashier at Chevron. He was made aware of the city’s plans when they did a survey, and he said his coworkers are in support.

Eernissee says they plan to offer all of the businesses displaced leases elsewhere in Downtown Everett.

“There’s a process to follow here. We are doing our part in following that prescribed process,” Eernissee said.

This process typically includes feasibility studies, environmental reviews, public meetings, and formal approvals from city and state agencies. It also involves finalizing funding agreements — such as bonds, grants, and private investments — alongside competitive bidding for design and construction.

Criticism of stadium subsidies

As a publicly funded economic development tool, stadiums have drawn criticism for often falling short of their economic promises. In 1997, two Brooking Institute researchers — Andrew Zimbalist and Roger G. Noll — wrote a book raising the alarm that publicly funded stadiums were a bad investment and failed to live up to their rosy projections, but the practice has persisted relatively unabated.

“A new sports facility has an extremely small (perhaps even negative) effect on overall economic activity and employment,” they wrote. “No recent facility appears to have earned anything approaching a reasonable return on investment. No recent facility has been self-financing in terms of its impact on net tax revenues. Regardless of whether the unit of analysis is a local neighborhood, a city, or an entire metropolitan area, the economic benefits of sports facilities are de minimus.”

Even when stadiums spur significant redevelopment, they have drawn criticism for furthering displacement and siphoning money away from social infrastructure. For example, Nationals Park in Washington, D.C., was a publicly funded MLB stadium that ultimately cost $693 million by the time it was completed in 2008. Built to anchor redevelopment in the Navy Yard, it did spur real estate investment and boost tourism, but it also drew criticism for relying heavily on public money and failing to address housing affordability or racial equity concerns.

Located in a retail and warehouse area, Everett’s stadium will not directly displace residents. “The good thing about this project is that there’s no residents affected,” Eernissee said.

The City has pledged to uplift existing communities and support local businesses, promising it could be a massive boon for the city.

As a minor league stadium, the scale of investment is smaller than big league parks, but similar risks exist. If the stadium and associated redevelopment only results in benefits for sports team and rich investors, or if it becomes a long-time liability sapping City resources, it may go down in history as a boondoggle.

What community members are saying

Residents have raised a few different arguments against the new stadium build, the most prominent being relocation of small businesses.

“I’m incredibly annoyed that the stadium isn’t being entirely privately funded. Who asked for this? It’s fine where it is. Meanwhile we don’t have any park rangers in the city and our library services have been cut,” an Everett resident complained on Reddit.

But Tarver says that these are misconceptions.

“There are some major misconceptions about this project, like what funding the City would be using, the idea that this funding could bring back park rangers (it couldn’t), that this adds to the structural deficit (it doesn’t), and why Funko Field isn’t a viable option,” said Tarver.

Some Everett residents shared the fear the new stadium could ramp up displacement pressure and change the neighborhood.

“The proposed site is in the middle of a historic district.” said Louley, an Everett local, when asked in an online poll about the community’s idea of the new project. “In the past 20 years, this neighborhood has completely turned itself around. We are a tight-knit community that looks out for each other, as well as the large unhoused population that travel through on a daily basis.”

“Putting a sports stadium in the middle of our neighborhood is going to undo EVERYTHING. North Everett has really been leading the positive changes in the city, but because historically this was a ‘slum,’” Louley added. “The entire county wants to raze us to the ground.”

On the other hand, some Everett residents back the project and favor out with the old, in with the new. Sverre is one such Everett resident.

“I think long term it will be great for the city,” Sverre said. “The current facility is owned by the school district, and its priority is for student use. Players have to cross the football then up the hill to even get to the locker room or trainers offices, which are the EHS football team locker rooms. They haven’t been updated in 50 years, and are massively outdated, even for high school sports use, let alone professional athletes. It would cost way too much to upgrade Funko field to meet new MLB standards, and it still wouldn’t be owned by the team or city.”

Beyond improving the stadium experience, Sverre sees the project as furthering the revitalization of downtown: “This new stadium is going to connect downtown Everett’s core, with the east side of Broadway, which has fallen in disrepair and is mainly older manufacture type buildings and old warehouses. It will bring a large amount of new urban housing and commercial spaces that will link up with the Everett Transit Center. This is also where the downtown light rail station will be built. I know future development will follow.”

Looking forward

As Everett pushes forward with its vision for a modern, multipurpose stadium, the project stands at a crossroads between transformation and tension. For some, it represents long-overdue progress—an investment in economic development, public amenities, and city pride. For others, it raises concerns about displacement, equity, and whether the return will truly match the cost.

At the end of the day, one thing is clear: this isn’t just about baseball. It’s about identity and the kind of future Everett wants to build. With construction slated to begin in 2026 and a completion date eyed for 2027, the stadium is beginning to look like a done deal, but it will be a test of the city’s planning prowess and commitment to inclusivity, transparency, and thoughtful urban growth to ensure it’s a success.