Other amendments from Alexis Mercedes Rinck would remove parking mandates citywide, and allow corner stores on all lots, not just on corners.

Citywide Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck is pushing for Seattle to take a few steps back toward a more ambitious growth strategy that Mayor Bruce Harrell’s administration had previously left by the wayside. In amendments to the One Seattle Comprehensive Plan set to be discussed this Monday, Rinck proposes restoring eight previously studied neighborhood centers that didn’t make it into the final plan.

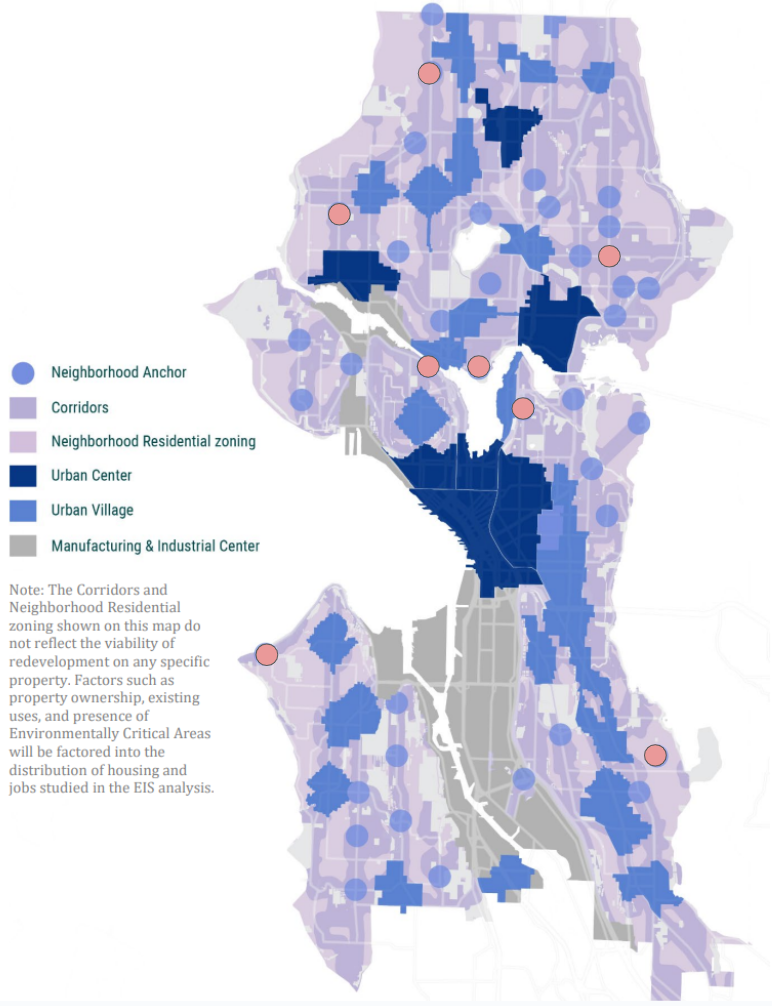

The restored neighborhood centers, in Alki, North Capitol Hill, South Wallingford, Loyal Heights, South Wedgwood, Broadview and Seward Park, would match the 29 other proposed centers around the city in bringing zoning changes allowing larger apartment buildings and commercial zoning intended to foster larger business districts. Sited in areas that already have access to significant amenities, these centers are a natural place for additional density, but were cut after the plan’s early scoping, using opaque criteria, which raised concerns among housing advocates.

“Simply put, we need more housing. Being able to build more housing across the city is a major step we can take towards addressing our affordability challenges,” Rinck told The Urbanist in an interview this week. “Our city is continuing to experience tremendous growth. We see from recent numbers, what 20,000 new neighbors coming in [in the last year], we are a city that increasingly folks across the U.S. are turning to whether they’re seeking refuge for whatever reason: political refuge, social refuge, to be able to get the care that they need, and so us preparing ourselves as a city to be able to accommodate for that growth, will allow us bring in our new neighbors and have the housing that we need, so we’re not also pushing working folks out of this city.”

Restoring these neighborhood centers had been a big focus of the Complete Communities Coalition, a group of advocacy organizations focused on improving the One Seattle Plan. (The Urbanist is a member of the coalition, through its advocacy team.) While groups like the Seattle Planning Commission have also offered other recommendations to improve the plan — including growing the boundaries of existing neighborhood centers — adding proposals into the mix that weren’t previously studied in the plan’s environmental review adds more challenges and would face significant headwinds. Restoration represents a more clear pathway to improving the entire plan.

“By adding neighborhood centers to the map, we can support the kind of livable walkable communities city-wide at a smaller scale than our urban centers (formerly known as urban villages),” Futurewise’s Jazmine Smith wrote in an op-ed making the case for restoration back in June. “Doing so works to undo the compounding historical impacts of redlining and housing discrimination and reduce displacement pressures in South Seattle.” (Smith is also co-chair of The Urbanist Elections Committee and a member of The Urbanist board.)

While the city’s seven district councilmembers have been deep in negotiations over specific blocks of potential neighborhood centers, Rinck made it clear that she wanted to push in the other direction as a directly elected representative of the entire city.

“As a citywide council member, I take it as: we have an opportunity to be zoomed out and looking citywide and really taking a balanced approach to where we’re developing across the city,” Rinck said, noting that historically, Seattle’s growth has been far from equal across the city. “We’ve done neighborhood walks with concerned residents across the political spectrum, but I think being we’ve been able to marry both district specific-concerns while also taking a citywide approach and reckoning with historical harm.”

Two potential paths on parking mandates

Rinck has proposed two major amendments tackling the topic of how much off-street parking builders should be required to include in new development. One amendment would bring Seattle in line with Senate Bill 5184, approved by the state legislature this spring, which dropped the ceiling on required parking to one stall for every two units of housing and two stalls for every 1,000 square feet of commercial space, with exemptions for apartment units smaller than 1,200 square feet, mixed-use commercial spaces, and affordable and senior housing.

Seattle isn’t required to comply with SB 5184 until early 2027, but folding compliance into the Comprehensive Plan would get that step out of the way early and allow builders to start building less parking if they determine it’s feasible for their specific project. The proposal in the One Seattle Plan now would drop mandates to one stall for every two units, but without the exemptions included in the Senate bill.

Rinck’s other amendment would go even further, following in the footsteps of Spokane, Bremerton, and Bothell in fully ditching all minimum parking requirements from Seattle’s land use code.

“Our parking mandates just make it more expensive to build housing,” Rinck said. “And if we really are building towards a green energy future, we need to be encouraging more folks into taking transit, increasing pedestrianization, and improving our transit connections. [I’m] hoping that we can make some progress in alleviating some of the requirements around parking when it comes to development.”

Corner stores: not just for corners

Rinck is also targeting the issue of allowing neighborhood corner stores, letting business owners open shops in residential areas that are currently off-limits. The mayor’s One Seattle proposal would legalize corner stores and neighborhood cafes, but only literally on corner lots, despite longstanding examples of grandfathered-in cafes located mid-block that work great. Another Rinck amendment would remove that restriction — along with extending the potential hours that cafes can be open.

“It seems like an arbitrary policy decision in a number of ways, especially given the value that small, little neighborhood spots — corner stores, however you might define that — the benefit that they can add to a neighborhood,” Rinck said. “And it’s a funny thing, because the limited number of corner stores that exist in neighborhood residential areas that do exist are so beloved and busy, which I think just speaks to again, the value and vibrance they can bring to a neighborhood.”

Improving the Harrell Administration’s corner store proposal has been a priority for Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, with more amenities in neighborhoods that people can walk and bike to a clear goal.

“Every neighborhood deserves places for community members to gather, buy essential goods, create art together, and build a community,” the group wrote in an action alert created in conjunction with Futurewise and the Greater Seattle Business Association (GSBA). “But right now, that kind of commercial and community space can be hard to find or afford. Legalizing corner stores would help bring these services and community spaces to every neighborhood.”

In pushing the One Seattle Plan in a more bold direction, Rinck told The Urbanist that she’s optimistic that she’ll be able to bring other councilmembers along.

“I think the data is clear that when we’ve seen cities increase their housing supply through land use changes, the cities that have done that increase their housing supply, [and] they’ve seen a drop in rents or some amount of stagnation,” Rinck said. “I think a number of folks on this floor [of councilmembers] see that, understand that, and hear the demand for housing at this point. We’re not just hearing from people who are experiencing housing instability, or folks who are rent burdened. I’m hearing from homeowners who are retirees who are concerned about the housing crisis because their kids got priced out of the city, and they want to be near by their grandkids. So it’s become a real unifying issue.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.