Renton can and should have better transit, and Michael Westgaard, a labor and community organizer with Raise the Wage Renton, is pushing to implement a more sustainable and equitable vision for the city. This, along with his belief in “sewer socialism,” has motivated him to seek Position 1 on Renton City Council in this year’s election.

Westgaard is challenging incumbent Councilmember James Alberson, Jr. for the seat. A former Renton Chamber of Commerce board president, Alberson has held the seat since 2022. However, Westgaard is leading him in campaign fundraising and has the backing of the MLK County Labor Council.

Recently Westgaard sat down with me for an interview to discuss his transportation plans in greater depth, as they are a key pillar of his campaign platform.

The current system is somewhat adequate for commuters in the city’s center, but it’s far from capable of serving the broader community holistically. Developing a robust and reliable bus network now will not only help Renton maximize efficiency and optimize land use, but prepare a system that will be able to feed passengers into the Stride bus rapid transit stations and perhaps eventually a Link light rail station.

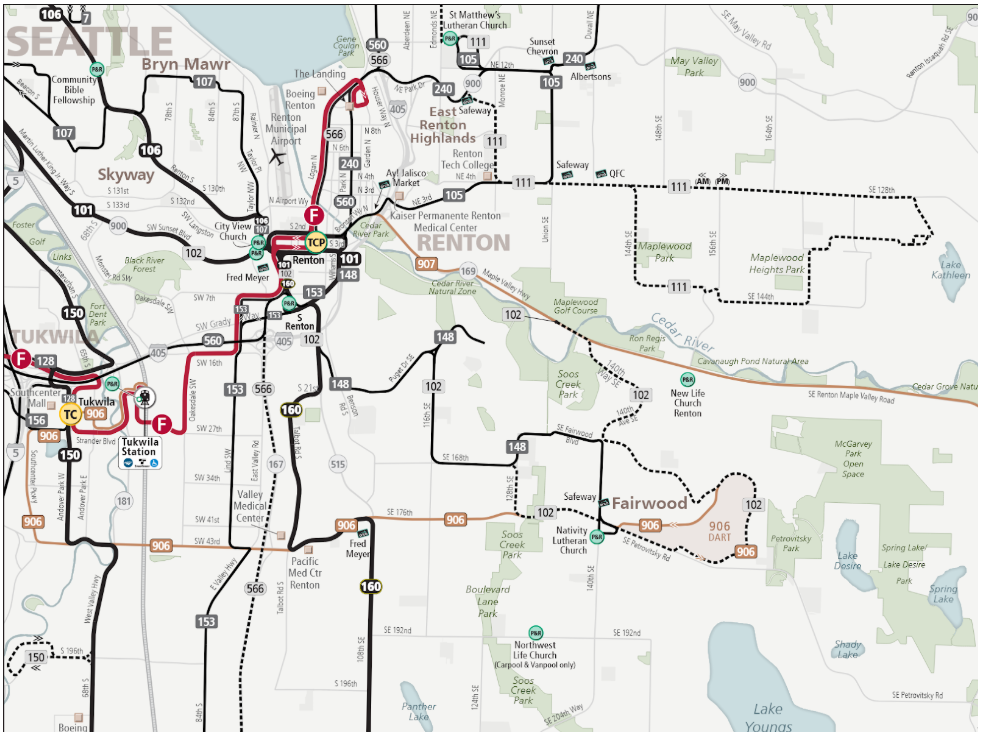

Renton is still largely a city designed around cars, but it does include a significant transit-dependent population that relies on the RapidRide F Line and a handful of other bus lines, many feeding into the city’s transit center. This wouldn’t be so much of an issue were it not for the system’s unreliability: King County has identified four Renton routes – the 107, 106, 111, and the 153 – as falling beneath its 80% on time performance. For the 111 in particular, this means Metro is having difficulty meeting the expectation of unidirectional rush hour only service to Renton’s eastern neighborhoods.

Westgaard told The Urbanist that the system can and should have more routes, the main immediate priority is to increase reliability: “If you have an unreliable transit system, people aren’t going to rely on it, and they’re going to figure out other ways to get around. If that’s your only option, then you’re just going to be stuck waiting, hoping, and stuck with the consequences of being late.”

Westgaard’s appreciation for a reliable system is derived from his own experiences utilizing the current system and confronting its inadequacies.

“At one point, I was trying to figure out how to take Metro to work to see if it’s an option, because the county will give you a benefit for not polluting,” Westgaard said. “ So I signed up for reminders from Metro. I appreciate the notification, but if you don’t get notified until 30 minutes or even an hour before, your options are limited to get alternatives to get where you need to be.”

Westgaard is floating the idea of Renton creating its own municipal transit agency or benefit district to fulfill his ambition to increase reliability:

“Metro does what it can, but since they have to cover a full region, once you start getting out into the suburbs, there’s just not enough capability to cover stuff,” Westgaard said.

Westgaard also feels a transit agency would be an important means of unlocking funding mechanisms to support necessary improvements.

“The only way we’re going to [a more reliable system] is through the municipal code,” Westgaard said. “Cities are allowed to start their own transit agencies, and then they get the taxing authority to do it… We have the taxing base. The other agencies that are able to do it, they’re able to do it on a 0.3% sales tax. I think there’s other ways to do it.”

In the spirit of Donald Shoup’s seminal work The High Cost of Free Parking, Westgaard has identified paid parking as a means to fund transit.

“Street parking and parking at the transit center in downtown, it’s free for 24 hours. That’s a great service, but it does two things: by building a parking structure you’re limiting the land use, not to mention all the sprawl parking. You could really make better land use if people could get around more conveniently.”

Reliably connecting Renton’s neighborhoods to the wider RapidRide and Link systems is a key priority for Westgaard, as an effective example will inspire support for future expansions.

“If we don’t find a way to connect people to those systems, then they’re gonna be less useful, and it’s going to be another example of why transit doesn’t work. Whereas if we invest in them and actually get people to those lines, it’s gonna do two things: it’s going to make it easier to get around, and it’s going to show that transit works and is an option. It will make it more reliable because once more people are using it, agencies will invest more into it.”

Westgaard has a deep appreciation for the responsibility of government agencies to use tax dollars effectively, gained from working in the public sector of wastewater treatment. He feels well-planned long-term investments in transit are important because they ensure public dollars are spent on projects once on a comprehensive vision, rather than piecemeal on addressing past short-term blind spots.

“One of the big things that I’ve come to believe is that, on public projects, because of the hate that people stir up about tax and bond dollars, the projects become more about whatever number is going to get printed on the completion announcement than what the actual system is actually being implemented,” Westgaard said. “One thing about value engineering, it’s death to projects in my opinion. I understand, we have to respect public dollars, but doing it right the first time is the best way to respect them.”

Regarding the political feasibility of the project, Westgaard is optimistic: “I think a transit agency is possible. I think it will take pressure, but based on the makeup, I think the majority on the council, they have their political ambitions, but they want to serve people. They didn’t get in just because of political ambitions, I believe. I think there are some people who are committed to people’s needs like Carmen Rivera, who has been a bold leader from her seat.”

A new transit agency for Renton isn’t just a panacea, however, and would increase the risk and responsibility of city management. Everett has demonstrated the potential pitfalls quite thoroughly, as its agency has suffered from a myriad of issues and resulted in it seeking to merge with Community Transit. While Westgaard is open to any and all ideas to improve transit in Renton, like replicating the Seattle Transportation Benefit District (TBD) which pays Metro to boost local bus service, he thinks Renton is in a position to succeed where Everett has failed.

“I will follow the data though,” Westgaard said on the topic of an agency versus a TBD. “The most important thing is making transit successful, and that is done through housing density and limiting space taken up by parking.”

Westgaard is looking to fight displacement and racial segregation, which is tied to housing unaffordability and environmental justice issues. Many poorer people of color are forced to live in high-pollution areas near oversized urban highways or “stroads.”

“It’s connected to the control of property,” Westgaard said. “There’s a class of people that have been able to buy a house in a previous generation and it’s stayed in the family, and they’ve used that property to get more property, and then there’s another class of people for whom that’s unobtainable or their options are different. It’s not gonna be a house, it’s gonna be a condo or a townhouse, and it’s gonna be on a stroad in a polluted neighborhood with a highway going by, and it’s not the same experience as being in a nice community.”

A major aspect Westgaard’s vision seeks to ensure people can access affordable housing in pleasant urban spaces by increasing density, rather than be confined to polluted stroads:

“If we start to build for density, the majority of people can have that,” Westgaard said. “We can get a transit system that gets people around by walkable bikeable paths.”

Density is how Westgaard seeks to connect his principles of equity with progressive urbanism.

“What I envision is you use walking and biking trails to connect neighborhoods together so that when people get home, if they wanna go walk with their kids, you can more freely walk on a walking and biking trail where you’re not worried about getting run over by a car,” he said. “You can go see your neighborhood and have an afternoon or evening walk. You can have bus stops connecting them. You can take that same easy walk and commute, and if people want to ride electric bikes they can ride them to transit centers.”

Westgaard sees municipal decisions on zoning as key to ensuring Renton capitalizes upon opportunities for equitable development.

“There’s been a lot of cool work done at the state legislature, and I definitely wish they would have gone farther, and really went after revenue,” Westgaard told me. “Allowing for housing to be built on park and rides, it’s going to come down to people at the city level actually taking that legislation and actually doing something with it. Because a couple years ago they passed the missing middle bill, and besides in very specific regions in the city of Seattle and Spokane, we haven’t seen a lot of action with it. Most of the other cities, they haven’t tried to get creative, they haven’t tried to figure out. They’ve been hung up on trying to protect ADUs as an option, which is a good option, but you know, it’s comparing building livable communities with building tiny village housing.”

Demand for more holistic transit systems beyond commuter service is well-supported by the data. King County Metro’s weekend service has recovered more ridership than weekday service post-Covid, showing transit is becoming not just a means of avoiding traffic and saving on gas for commuters, but a way of life. Westgaard hopes capitalizing upon that demand at the municipal level will demonstrate transit’s opportunities to state-level decision makers, making Washington a more sustainable and equitable state overall.

“As you’re building out these walking and biking trails and connecting these neighborhoods, and you make transit an option, and ridership goes up and it becomes popular, it’s going to have the state’s attention,” Westgaard said. “Then, instead of expanding highways, which time and again has been shown to create more traffic, then we can start investing in our transit systems, and making them functional. We have to bring the people to it, because people are going to do what’s convenient and reliable. When you’ve got to be at work or you’ve got to be at the doctor’s appointment, or your kid’s got to be at school, you’ve got to be there.”

Editor’s note: The Urbanist Elections Committee did not endorse in Renton City Council races during the primary, but may revisit them during this fall general election.

Collin Reid

Collin Reid is an educator who moved to the Central District of Seattle in 2024 after having lived and worked in St. Petersburg Russia for eight years. His background in political science and international experiences led him towards urbanism and transportation as the foundational elements of society. He is a member of the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America.