The Sound Transit board Thursday adopted a set of principles intended to solve financial issues that threaten to derail transit projects across the region, in the wake of new estimates that put the agency’s long-term financial shortfall at anywhere from 30 to 40 billion dollars.

The work ahead represents what is likely to be the most important 18 months for Sound Transit since the early 2000s, when the fledgling regional transit system was rescued from the brink of financial ruin. Among the issues set to be put on the table are major elements of the planned Sound Transit 3 (ST3) expansion plan, including the necessity of a second, regionally-funded light rail tunnel under downtown Seattle, and the scope of other planned extensions.

The reset has been signaled for months, with CEO Dow Constantine briefing board members on the so-called “Enterprise Initiative” at their annual retreat this spring. Unlike past program realignments, including the one implemented in 2021 in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, this reset is set to tackle the entire agency, including its growing operations division and the way that Sound Transit structures its finances.

The projected financial gap announced this week, which could approach 25% of Sound Transit’s entire financial plan, includes a $20-$30 billion shortfall impacting its system expansion projects, on top of a hit of $4 to $5 billion in decreased revenues. It also includes a $5 billion expense the agency will need to grapple with when it comes to increased service delivery costs. Those extra service dollars include new train cars, along with projects required to make the system more resilient, including a badly needed new crossover track in downtown Seattle to minimize service disruptions.

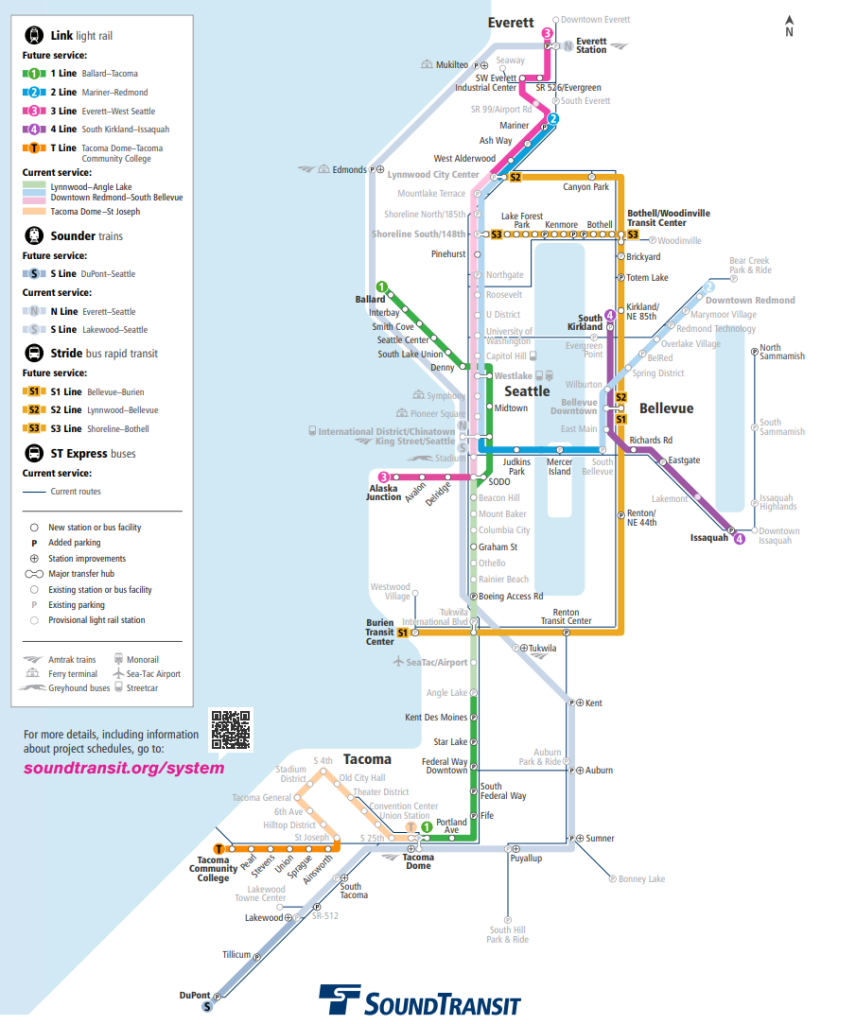

The $20-$30 billion capital funding shortfall is the first comprehensive look at the financial health of the 2016 ST3 plan, and comes on the heels of a public announcement last year that the first major ST3 project to start planning — West Seattle Link — has seen costs escalate by around $3 billion. While scope and schedule changes are likely on the table for even bigger ST3 projects, including Everett, Tacoma Dome, and Ballard Link, it’s too early to know how those projects might be adjusted in order to move forward within Sound Transit’s budget.

“We have in the past dealt with these challenges by pausing all our work, by cutting lines, by using really just these blunt instruments. We want to do better,” Constantine told reporters in a briefing ahead of Thursday’s board meeting. “The Enterprise Initiative is really the framework that allows us to go beyond what we did before, which is just focus on capital and just focus on scope and schedule instead to do the hard work, the innovative work, the careful, meticulous work to save money, to have a better product, to reduce construction impacts, and ultimately, to have a balanced long range financial plan and move forward building a system that people asked us for.”

The motion approved Thursday calls for Sound Transit to update its System Plan, Long Range Plan, and its Long Range Financial Plan, all by the end of next year. Sound Transit staff will be tasked with identifying a “new process to proactively and iteratively manage affordability, service delivery, and related issues.” A significant portion of that work will fall to Terri Mestas, who joined Sound Transit as the agency’s deputy CEO for megaproject delivery last year and has been leading the work to find ways to reduce costs on the hotly anticipated ST3 projects.

What was clear Thursday was that fundamental assumptions related to the buildout of the ST3 network are set to be put on the table, including the plan’s most expensive project — a new tunnel between SoDo and Interbay through Downtown Seattle as a part of Ballard Link. Due to the regional benefit that tunnel would provide for the ability to maintain consistent frequencies, it’s set to be funded jointly by the entire region. But King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci suggested giving it another look.

“I think we need to ask all the big questions, and not shy away from them,” Balducci said. “Do we need the second downtown tunnel? I think we need to ask ourselves that question. It is a major part of the contribution of every subarea in this program. The current plan has been based on assumed constraints on headways and throughput and reliability through the tunnel. Those may continue to maintain, but we also know we have different technology that we have not deployed that could increase reliability and throughput.”

Balducci acknowledged that jettisoning the second tunnel in downtown Seattle would bring tradeoffs, including less passenger capacity and resiliency through the heart of the network. But she framed it as irresponsible to not at least study the idea. Balducci has suggested similar studies of outside-the-box concepts before, such as overhauling the agency’s split-spine concept, but was rebuffed at the time by her colleagues, including now CEO Constantine.

“There’s some real benefits. We could save a lot of money. We could deliver West Seattle to Ballard and the spine faster. We could potentially defer or avoid impacts to downtown Seattle and potentially solve this entire debate we’ve been having about what to do in the Chinatown-International District,” Baldduci continued.

With board members continually reaffirming their commitment to the regional light rail “spine” and the full ST3 network, the tough decisions ahead will likely put competing values including ridership, connectivity, and geography at odds with one another. Balducci is also pushing to adopt consistent service delivery standards that will guide how the board makes decisions around prioritizing segments.

“I’ve really been encouraging people to think big to blue sky. So that means that questions that used to be thought asked and answered can be reopened, whatever they happen to be,” Constantine said. “We’re not going to be weighed down by the assumptions of the past. We’re going to figure out, based on what we know now, how to build this thing and operate this thing sustainably.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.