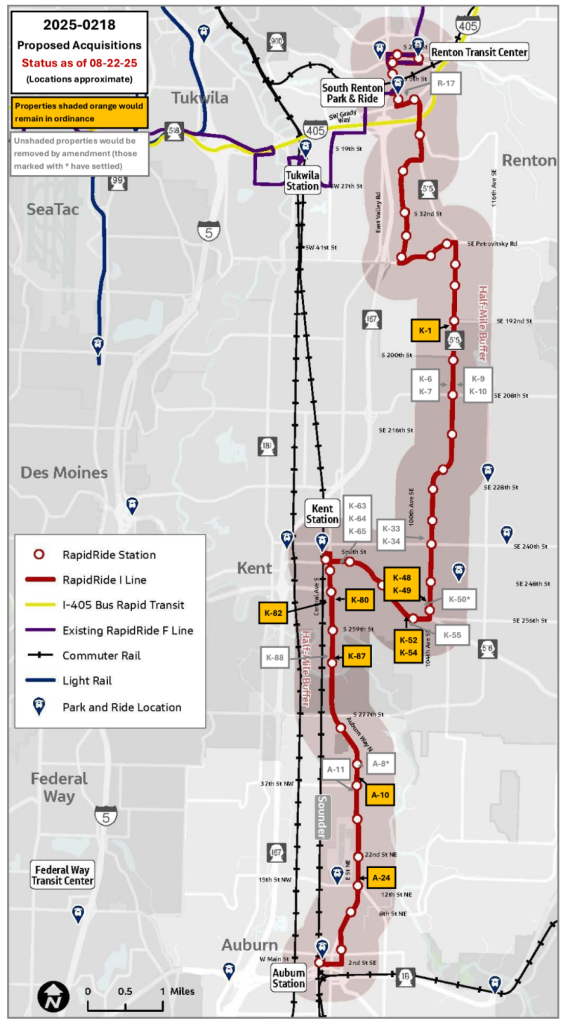

A county council committee this week voted to authorize a set of property condemnations intended to ensure that King County Metro’s next RapidRide project, the I Line between Renton and Auburn, remains on schedule. The $174 million project is set to start construction this fall, but Metro has not yet secured the rights to build bus stop upgrades and transit improvements on a few dozen properties up and down the corridor.

Monday’s unanimous vote in the transportation, economy, and environment committee represented a scaled-back version of the initial broader condemnation proposal. After initial consideration of 25 potential condemnations in July, several councilmembers had raised concerns over the number being that high, even as county officials provided assurances that there would likely be more settlements reached before condemnation authority was actually used. At that time, there were also issues raised around what public notice had been provided to impacted property owners, with several showing up directly at a council meeting with concerns.

Condemnation is generally used as a tool of last resort when local governments need to acquire property, but direct negotiations reach a full impasse. By the time of yesterday’s committee vote, the number of properties included had been whittled down to just 10. Of the 15 properties that were taken off the list was the White River Buddhist Temple in Auburn, where Metro remains in negotiations around potential modifications that would lessen the impact on a religious institution. Of the other nine remaining properties, one more is in Auburn, with the other eight in Kent.

Overall, the I Line is set to require 110 individual property acquisitions and construction easements, primarily to make room for upgraded transit stations that include rider amenities like off-board payment infrastructure, seating and lighting, and real-time information signs.

Without approving the condemnations, the I Line risks running behind schedule, which could put its federal funding at risk. The $80 million grant Metro received from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), transmitted in the final days of the Biden Administration, makes up nearly half of the full project’s cost. Initially scheduled to be delivered in 2023, the I Line has already been subjected to numerous delays during its design phase. As a result, its targeted opening has slipped to 2027.

“Condemnation authority is not something that we take lightly, and even though this ordinance does not involve the full taking of any property and does not impact any buildings, I think it behooves us to ensure that the process itself is transparent, and that legislation is narrow as possible, while still enabling Metro and the amazing work that Metro is doing to move forward with this important project for all of those in affected in South King County,” Councilmember Sarah Perry said Monday.

Among the councilmembers raising questions about the idea of potentially condemning 25 properties was Rod Dembowski, who had drafted an amendment for Monday’s meeting requiring Metro to give the council 60 days to review any condemnations before proceedings actually moved forward, allowing time for that authority to be repealed on an individual basis. A real estate attorney by training, Dembowski was a partner at Foster Pepper and chaired their real estate litigation practice group before being appointed to the King County Council in 2013 — filling a vacancy created by Bob Ferguson winning higher office.

Despite his earlier concerns, Dembowski withdrew his amendment at the meeting, seemingly placated by the reduction in the number of properties included.

“My concern with this legislation was its breadth, but more importantly, that there was no indication that the dozens of property owners had received any notice that the Executive transmitted a condemnation ordinance to the council and that we would be considering it and voting on it, and no notice to the affected property owners,” Dembowski said. “I hope this will not happen again. If we are going to be considering condemnation of people’s property, they ought to have notice early, not late or not at all. And so I hope we’ll do better in the future.”

The RapidRide I will be King County’s first bus rapid transit line to be built fully outside the City of Seattle since the F Line in 2014. It will serve an area of the county that saw remarkably transit strong ridership throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.

By upgrading the existing Route 160 with dedicated transit lanes and signal priority at intersections, Metro expects to save riders going from one end of the corridor to the other around 8 minutes by 2040, as traffic congestion levels increase. That’s a significant savings, but for such a long route it’s less dramatic than the time savings seen in other RapidRide corridors, like Madison Street’s G Line.

With around 5,500 riders currently using the 160 every weekday, Metro expects to see ridership increase by around 50% by 2040, to 8,500 daily riders.

“We are trying to balance very real rights and very real needs,” Councilmember Claudia Balducci said. “The property rights of the property owners that are being impacted are very real and need to be respected and treated fairly. The people who are going to ride this line when we build it to the standards that we commit to for RapidRides, where it is fast, frequent, reliable, especially for people, many people who ride our RapidRides rely on our busses for their everyday transportation, and so […] not watering down the line is very important, a very important interest here.”

The full county council is set to vote to approve the condemnation authority in early October.

The I Line is set to open within a few months of the City of Seattle-led RapidRide J, between Downtown Seattle and the University District. After the I and J, King County Metro doesn’t expect to open another RapidRide line until the Eastside’s K Line in 2030 and the R Line upgrade of Rainier Valley’s Route 7 as soon as 2031. Beyond that, RapidRide expansion plans remain murky and threatened by Metro’s looming financial crunch.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.