Mayor Bruce Harrell has rolled out a proposal to spend $80 million over the next four years on an “anti-gentrification and reparations fund,” seeking to right past housing injustices against Black Seattle residents. At the press conference held at Bryant Manor Apartments in Seattle’s Central Area Wednesday, Harrell also trumpeted $350 million in Seattle of Housing investments he aims to make in 2026, which he portrayed as record investment.

The mayor sketched out the reparations fund in general terms rather than hard details, but he did say it would feature down payment assistance and rent assistance. Proponents said a change in state law (House Bill 1918) would make the program square with the Fair Housing Act, which limits the extent to which governments can target housing benefits solely to members of one race.

To fund his proposal, Harrell is banking on revenue from the overhaul of business and occupation (B&O) taxes, dubbed the Seattle Shield Initiative, which voters will be asked to approve in November. Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck spearheaded the initiative, with Harrell’s support helping win over her centrist colleagues, who last month greenlit the idea of the measure on the ballot.

With repeated delays and cuts to the mayor’s growth plan (some self-inflicted), zoning is not a tool that the mayor was able to deploy in his first tool to lessen displacement pressure and seek to reverse racist redlining practices that pushed people of color out of Seattle — especially Black residents. If housing prices continue their precipitous climb in Seattle, rent subsidies and down payment assistance will become an increasingly expensive proposition — while still likely representing a modest band-aid on a growing wound.

On the other hand, residents struggling to afford housing will likely take any help they can get.

Harrell ramps up attacks on political opponents

During his Q&A with reporters, Harrell became heated, alluding to attacks against his administration he deemed unfair and firing back at opponents.

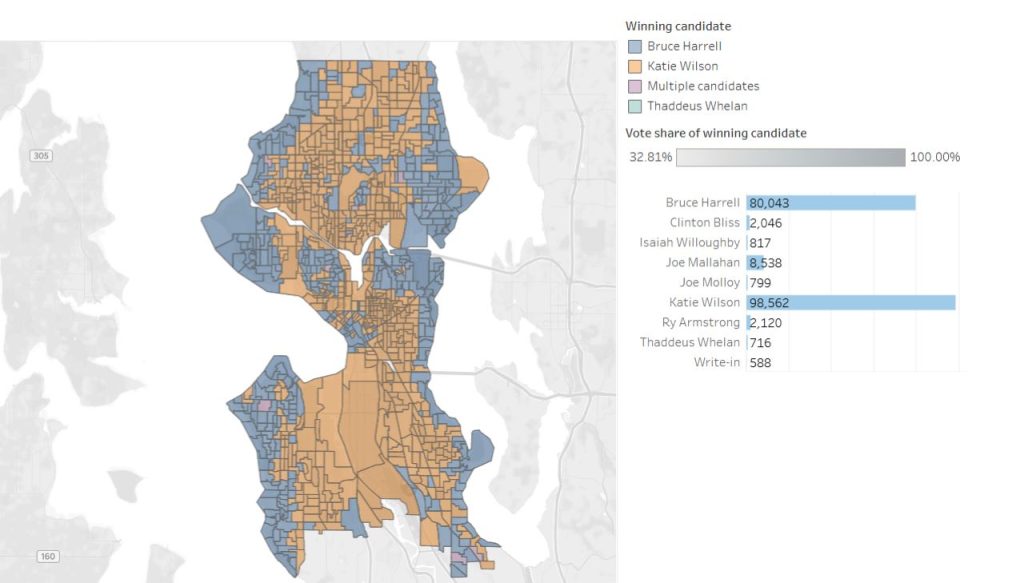

Harrell is in a tough reelection fight with Seattle Transit Riders Union head Katie Wilson, who has criticized the mayor’s approach to homelessness, housing, and economic justice. Wilson won the primary election by nearly 10 points, shocking Seattle’s political establishment who had sought to portray a second Harrell term as inevitable. (Full disclosure: The Urbanist Election Committee, of which I am a member, endorsed Wilson.)

Pundits have pointed to Wilson’s ability to connect with voters over the issues of housing and the rising cost of living as propelling her primary victory. That resonance helped Wilson win precincts in diverse working class areas in the Central Area, Beacon Hill, and much of the Rainier Valley, while Harrell did better in wealthier areas along the waterfront.

On Tuesday night, Harrell’s campaign sent out a press release criticizing Wilson’s homelessness plan, which aims to build 4,000 units of shelter in four years, as too expensive and impractical. The press release mistakenly claimed Wilson’s plan promised these 4,000 units in six months, which is inaccurate.

Harrell would know something about the perils of bold homelessness pledges after running on a promise to build 2,000 units of additional emergency housing for homeless people in his first year in office. He came up well short, not even identifying 2,000 emergency homes in his first year, let alone building them. Making matters worse, capacity in homeless shelters actually shrank under Harrell’s watch.

For their part, Wilson’s campaign criticized Harrell’s proposal to raise rent caps in new Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE) buildings. Later this month, the Seattle City Council is set to vote to approve the seventh iteration of the program, which trades a property tax break for landlords of new buildings setting aside a portion of apartments at more affordable rents. Typically, the requirement has been to rent 25% of apartments at 70% of area median income (AMI) — through studios have to hit lower AMI and multi-bedrooms can be higher. The remaining 75% of apartments usually remain market-rate.

A draft proposal would set the AMI-based rent caps lower initially, while allowing larger rent increases after the initial year in the program. About 7,000 homes are in the MFTE program, which is voluntary for landlords to participate in. Beyond producing rent-restricted homes, housing advocates argue a major benefit of the MFTE program is to spur housing development generally, which takes added importance as Seattle faces a housing slowdown.

“Instead of focusing city resources to build the affordable housing Seattle desperately needs, Bruce Harrell is championing changes to the MFTE program which would give developers millions of dollars of tax breaks to build housing that tenants can’t afford. Councilmembers should reject this proposal,” Wilson said in a statement. “As Mayor, I will work with renters, housing providers, and private-market developers to improve the MFTE program so our city builds more of the kinds of apartments working families want, need, and can afford.”

Harrell bristled at attacks from Wilson and her allies, and fired back at critics generally.

“How dare they write that under this administration, which has, by the way, the most diverse set of leaders on the Executive floor in our city’s history, how dare they write not sensitive to the needs of those who have been overlooked,” Harrell said. “I will remind all of you that it was a presidential executive order that put […] my mother in a concentration camp. So when I see executive orders coming out affecting communities of color, this is personal for me. So how dare anyone question the compassion of this administration toward people who are underrepresented, Black people, brown people, people of color, people who have been othered, such as the LGBTQ+ community. How dare anyone comment on us being less sensitive. For me, this is personal. This $350 million in a budget is personal. I don’t expect you to understand this.”

Harrell selected a friendly and familiar audience to make his announcement. First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church’s Housing Corporation built Bryant Manor Apartments, and the mayor noted — for the part of the crowd that didn’t overlap with AME’s congregation — his family’s close ties to First AME Church and its associated housing corporation.

“I grew up in AME Church,” Harrell said. “I served as the lawyer for the AME Housing Corporation for many years. My grandfather was on the usher board. My brother: an altar boy. Myself, a Sunday school teacher [and I] was married in that church.”

Seattle housing investment face headwinds in future years

Harrell’s $350 million figure is about the same as the previous year when adjusting for inflation, and warning signs do exist that housing resources will shrink in coming years without further action. That large housing investment comes from three primary sources: the JumpStart payroll expense tax, the Seattle Housing Levy, and payments from builders via Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) fees.

An MHA report from the Seattle Office of Housing noted that housing permits are down sharply, which means MHA fee revenue is also trending downward sharply. Those fees are due at permit intake; without development activity they dry up. The slowdown is already starting to hit the City’s housing trust fund, but the City underspending previous years’ revenue has provided some slack in the coffers.

That slack won’t last forever. This is especially true if Council President Sara Nelson and her allies succeed in using the Office of Housing underspend to patch over other areas of the City budget, as she has suggested.

Payroll tax revenue tends to trend with the economy, as well, with revenue decreasing if large Seattle companies shed payroll. Moreover, the practice (embraced by Harrell) of diverting payroll revenue toward the general fund to patch holes, rather than sticking with the original spending plan to set aside about two-third for housing, also threatens to lessen investment levels in future years.

Additionally, housing investment is facing pressure from high inflation, rising construction costs, and higher operating costs, in what some builder’s are portraying as a perfect storm. Operating cost woes have included some issues filling apartments (particularly in higher rent segments) and getting full payment of rents.

Harrell confirmed some of the $350 million investment would go toward stabilizing existing affordable homes in nonprofit building, rather than expanding affordable housing stock. The net effect of rising operating and capital costs is that each dollar invested leads to fewer homes, through Seattle still has been able to add thousands of nonprofit homes.

“In 2025 already this year, we’ve added 1,025 new units of City-funded affordable housing, and we’ve added more than 6,500 new units since 2022,” Harrell said.

The rollout of his reparations fund and the fiery press conference accompanying it marked a stake in the ground for a mayor battling to prevent his own displacement from City Hall. Whether a more aggressive tone and announcements like this one will be enough to hold on remains to be seen.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.