Leaders from transit advocacy organizations across Central Puget Sound gathered in front of Sound Transit headquarters Thursday with one clear message: “Build the damn trains!”

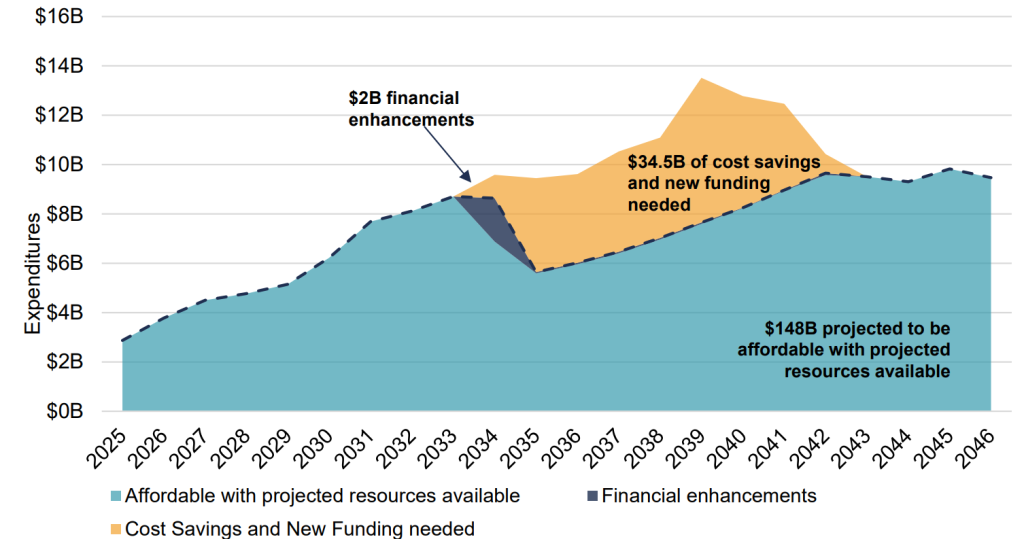

The phrase was initially a coinage of Seattle transit advocate Leonard Harrison Jerome, in response to a failed proposal earlier this year to add new permitting requirements to the city’s next light rail projects. But it has become a full-on campaign, as the Sound Transit board figures out how to grapple with a $30-$40 billion budget shortfall over the next two decades that could impact projects across the agency.

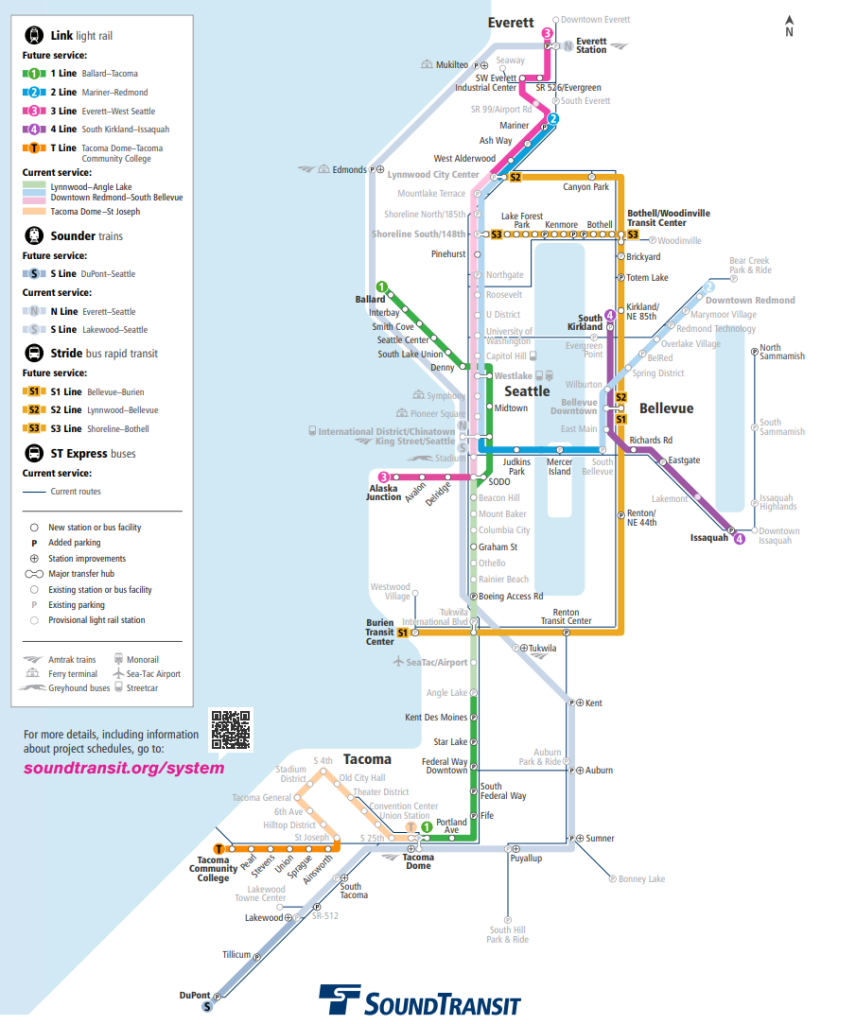

On top of lower-than-expected revenue forecasts and an expected need to increase operational expenses, that shortfall includes a $20 billion to $30 billion gap to complete the slate of new light rail lines approved with the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) package in 2016.

In just a year, getting light rail to the Tacoma Dome has gone from a $4.6 billion project to a $5.4-$6.1 billion one, and getting to Downtown Everett has gone from $6.5 billion to as much as $7.7 billion. The combined cost for West Seattle and Ballard Link has gone up anywhere from $11 billion to $14 billion.

The rally’s timing came just as the 18 members of the Sound Transit Board of Directors met for its second retreat of the year, as an opportunity to start to grapple with the decisions that are set to come by the end of 2026, when they adopt an updated ST3 system plan, a new regional transit long-range plan, and a new service guidelines network plan.

Standing in front of a crowd of light rail supporters, Kirk Hovenkotter, executive director at Transportation Choices Coalition, pushed back on the idea that Sound Transit board members might retreat into their corners to advance their preferred projects over others, and emphasized the fact that delay will ultimately make those projects more expensive.

That tendency was already on display this summer, when Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell held a press conference to announce that he didn’t support a delay on the city’s light rail projects, a move that led some board members from other cities to respond in kind and become more entrenched.

“Nearly a decade after this region approved Sound Transit 3, transit riders deal with unreliable and infrequent busses. Commuters are stuck in traffic, and voters are diligently paying their taxes to fund the promise of light rail, and they are sick and tired of the Sound Transit Board wavering on whether to build the light rail that voters approved in 2016,” Hovenkotter said, while wearing a “Build the Damn Trains!” shirt. “Over the last few months of the election season, we’ve heard board members call to cut light rail to West Seattle and the downtown tunnel. Now, that the so called silly season is over, it’s time for the board to get serious.”

But actually building the damn trains is easier said than done.

Costs for complex urban light rail lines — think West Seattle — are rising faster than less complicated projects through suburban areas, at the same time that elected officials in Pierce and Snohomish Counties voice louder frustrations about the fact that light rail hasn’t yet arrived in their communities. While Sound Transit’s capital delivery team, led by Deputy CEO Terri Mestas, has found some early wins that could free up hundreds of millions of dollars without significantly impacting future service quality, the entire shortfall will not evaporate with that work.

“Ballooning costs are making it challenging to deliver on these projects, and that’s why we’re here today to urge the Sound Transit board to look for very real cost savings measures: these might be smaller things like eliminating parking garages or standardizing station design, but it also might take some revisiting of some hard choices around alignment to make sure that we can deliver projects on time and in an affordable way,” Kelli Refer, Executive Director of Move Redmond, said.

Sound Transit does have enough funding to get its biggest future projects — including West Seattle, Tacoma Dome, and Everett Link — under construction. The problem is down the road, when projected costs are expected to quickly exceed available revenue by the early 2030s. Hovenkotter pushed the board to explore ways to finance projects differently than it has in the past.

“We want the board to look at the financial flexibility that they have before they jump to what they’ve done in the past, by cutting projects,” Hovenkotter told The Urbanist. “We want them to get more financial tools at the legislature, be able to be more flexible with the financial resources that they have. We know Sound Transit is a rich agency. It’s about when they have the money. And we want them to get more financial flexibility to be able to deliver projects when they need to build them.”

While many Seattle transit riders will point to Ballard Link, as the highest ridership project included in ST3, as one that should be prioritized ahead of others, delays elsewhere could have downstream effects. In an interview with The Urbanist, Tacoma on the Go executive director Laura Svancarek highlighted the fact that many residents in Pierce County have had their view of all transit projects colored by Sound Transit’s decisions.

“You really can’t discount the very real frustration that people in Pierce County have, and so every time our projects are delayed further, it makes it harder for Pierce Transit to do what they need to do to offer good local service or to ask the voters for more funding to provide better local service,” Svancarek said. “What we need is clarity, and what we need is really strong leadership from the board in putting real effort into exploring like: what options do we have that are not delays? What things can we put off? Do we really have to build parking garages? I think no.”

In providing opening remarks ahead of the board retreat, Sound Transit CEO Dow Constantine noted that decision points are going to come quickly in the months ahead, with board members expected to lead rather than take direction from staff. Some new faces will join the board in early 2026 to help make these decisions, which are likely to reverberate for decades.

Among the board shakeup will be the addition of Seattle Mayor-elect Katie Wilson and a new member for Girmay Zahilay’s seat, who will be taking a more influential role on the board by winning a promotion to King County Executive. County Executives have the power to appoint board members to the seats allocated to their county. Lynnwood Mayor Christine Frizzell lost her reelection and will also need to be replaced on the board, and Interim County Councilmember De’Sean Quinn is also leaving office after not seeking to retain the seat.

“From this point forward, the focus will sharpen and the pace will quicken. General principles will become decision points. Broad scenarios will crystallize into choices with which the board will need to wrestle our work as staff will be focused on supporting the board and on providing board members the tools they need for innovative problem solving and decision making,” Constantine said. “The new paradigm is one where it’s not the staff coming in and dropping fully baked solutions on the table, it is one where each of the people around this table, representing the entire region and their own jurisdictions, are bringing their creativity and their understanding of the needs of the people to help solve those problems.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.