Less than one-quarter of the $300 rebates awarded through a lottery were actually redeemed. WSDOT plans a follow-up round of rebate awards.

Washington’s first foray into providing cash rebates to spur new e-bike purchases left more than $1.6 million in unspent funds on the table after rebates were redeemed at lower-than-expected rates, a new state-produced report released earlier this month has revealed. The leftover dollars, which are likely to be rolled into the amount disbursed with the next round of rebates, remained on hand despite the fact that nearly 35,000 Washingtonians signed up for a chance to receive a rebate but didn’t.

The state launched its “WE-bike instant rebate program” this past spring after securing funding via a legislative earmark in 2023. The program allowed state residents to sign up for the chance at a $1,200 rebate or $300 rebate. The larger rebate was reserved for lower income households and required proof that a household is earning less than 80% of their county’s area median income (AMI) in order to qualify. The goal was to enable more residents to access an additional pollution-free mobility option, aided by funding from the state’s Climate Commitment Act.

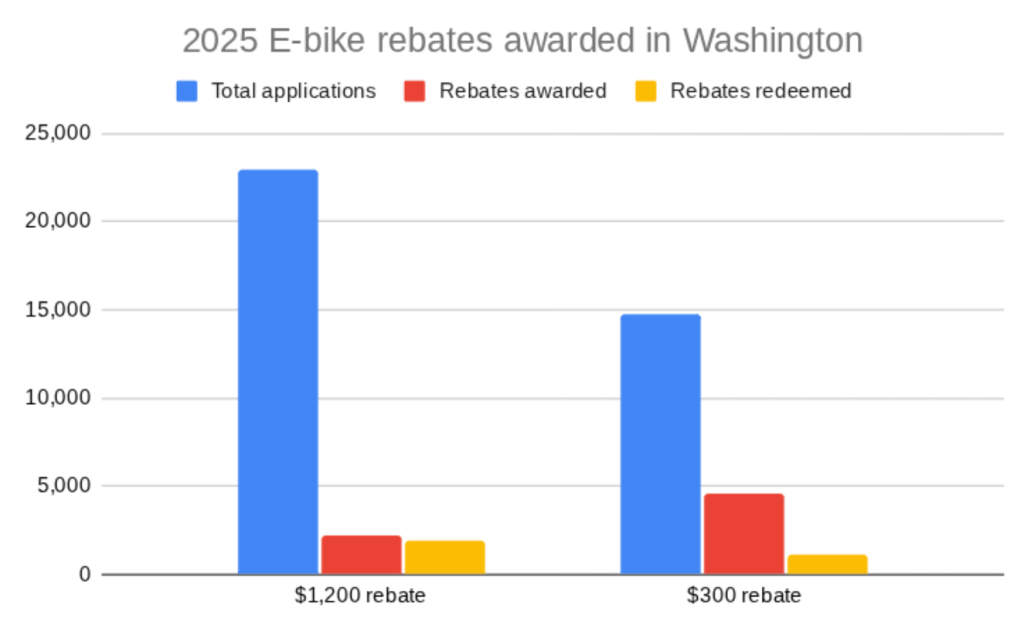

Despite the added paperwork, 55% more potential bike owners applied for the $1,200 rebate during the two-week application period in April compared to the $300 rebate, which meant that only 10% of applicants successfully scored the larger discount. But of those who did, 84% followed through and made a bike purchase — in contrast with just 24% of those who won the smaller $300 rebate.

Under a legislative mandate, 40% of the total rebate funding was intended for the pool of $300 rebates, but in the end less than 13% of the total dollars handed out went to those applicants, after a sizable majority let theirs expire without buying a bike.

Despite offering more than twice as many $300 rebates via random lottery than $1,200 rebates, the state saw 1,880 rebates worth $1,200 redeemed, compared to just 1,087 rebates that were worth $300. Clearly, the larger rebates provided winners with a much bigger incentive to see their purchases through. The unspent dollars could have helped more than 1,000 more low-income Washingtonians to purchase an e-bike

This first attempt at rebate distribution, which comes on the heels of other programs elsewhere in the US, offers some major lessons learned for the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT). In rolling out a rebate program from scratch, the department faced an impatient public and had to significantly tamp down expectations for the program, given the relatively small pool of money that was set to be available.

The report notes that low redemption rates have been seen elsewhere when rebates around $300 were offered, citing a San Francisco bay area program and a Tacoma program, which was offered to residents who live along I-5 at the same time as the statewide WSDOT program.

“[T]he $300 rebate appears to have been insufficient for many recipients, suggesting that some explored purchasing an e-bike but ultimately found the cost prohibitive,” it concludes. “With prices expected to rise further due to recent tariffs […] these affordability barriers are likely to become even more pronounced for lower-rebate recipients.”

The limited program clearly did provide significant benefits. As part of the rollout, WSDOT partnered with the University of Washington to survey rebate program participants, finding that only 6% of residents who failed to win one of the $1,200 rebate went on to make an e-bike purchase. Only 8% of lower-income rebate program participants reported already owning an e-bike, a group that was found to be much more likely to use public transportation as their primary way of getting around. Across both the $1,200 and $300 rebate, 17% of program respondents reported owning no car at all.

“The program also measurably improved access for e-bike purchasers,” the report states. “44 percent of study participants who purchased an e-bike stated that owning an e-bike allowed them to go places that they previously did not visit. 68 percent reported using their e-bike for trips they would have previously taken by car, 46 percent for trips they would have walked, 36 percent for trips they would have biked, and 33 percent for trips they would have taken by transit. These results suggest that e-bikes expanded the range of trips participants could make and offered an alternative to vehicles, biking on a traditional bicycle, walking, and transit for certain trips”

What the UW survey did not find was any measurable impact on the amount of driving trips made by participants before and after purchasing an e-bike, a major question when it comes to gauging the effectiveness of the program as a greenhouse gas reduction tool. Survey respondents used an app to track their trips, with the program automatically determining whether participants had been travelling via bike or car with a 88% accuracy rate.

“Neither the $300 nor the $1,200 rebate offers produced a statistically significant change in daily [Vehicle Miles Traveled] relative to their respective control groups,” the report states, noting the limited scope of the study, which concluded after six months. “Overall, we found no evidence that rebate recipients substantially reduced their vehicle travel. […] These results suggest that while e-bikes may have expanded participants’ travel options and mobility, they did not replace enough vehicle trips to reduce overall driving.”

Other studies, conducted either by GPS or self-reported data, have shown a decrease in driving rates from e-bike incentives, including in Canada, Sweden, and Norway, and the report takes pains to note the limited amount of data from which conclusions can be drawn. But in context with the other data points shown from this initial round of rebates, e-bike purchases seem to be enabling Washingtonians who would have gotten around without a car anyway to dramatically improve their mobility and travel options.

“E-bike rebates may require longer time periods and/or complementary measures to translate increased e-bike adoption into measurable reductions in vehicle travel. Expanding funding for more types of load-carrying equipment or other bike-related accessories, such as add-on equipment for transporting children, might also affect the extent and type of e-bike usage,” it notes.

The chances of winning a rebate are likely to be much higher in the program’s second round, expected in 2026, after the legislature earmarked an additional $7 million for the program. Governor Bob Ferguson’s proposed budget for WSDOT, released earlier this month, rolls over unspent dollars from 2025 into that amount, bringing the total to more than $9 million. But it will be up to the legislature to decide whether to keep that amount in place, and the data learned from the initial round of rebates is likely to significantly shape that decision-making.

Correction: an earlier version of this story stated that Washingtonians who weren’t offered rebates had received rejection notices, when they were simply not notified.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.