Deferring Seattle’s second downtown transit tunnel may be a last resort — but unless the Sound Transit Board demands a systematic strategy for closing its $35 billion funding gap, cuts are coming. And they won’t be small.

The most likely casualties are known: truncating the Ballard line at Smith Cove, reducing West Seattle Link to a single station at Delridge, eliminating Graham Street Station, abandoning Aurora/Harrison as a regional transit hub, and cutting the Boeing Access infill station. The prevailing wisdom among insiders is a repeat of the past, where work is phased and bailed out with future packages, whereby the next “ST4” ballot measure becomes completing Sound Transit 3 (ST3) – asking voters to raise taxes to make up for shortfalls on projects they already voted for and funded.

Delivering ST3 as promised to voters with current funding is possible, but requires political leadership and an appetite for a sea change within Sound Transit. One key is factoring long-term operational costs and imperatives into decisionmaking over capital projects.

Describing an elephant

This situation resembles the parable of the blind men and the elephant in which several blind men each touch a different part of an elephant and, mistaking the part for the whole, argue fiercely about the nature of the elephant — illustrating how limited perspectives each contain truth yet miss the full reality. Sound Transit faces multiple interrelated challenges — operations, engineering standards, financing, and federal process. Tackled independently, none provide a full picture of the opportunities to close the funding gap.

During a recent meeting, several Sound Transit board members dismissed deferring the second downtown tunnel because a preliminary analysis suggested it could only save up to $4.5 billion. By that logic, we should ignore proposed cuts to the Ballard extension or Graham Street because they only save ~$2 billion and $200 million respectively.

The Board should prioritize reversible (“two-way door”) decisions over irreversible (“one-way door”) decisions. Policy choices can be revisited, above ground stations (Boeing Access) can be deferred. Eliminating underground stations (e.g. Aurora and Harrison) is irreversible. Losing voter trust is a one-way door.

There is no single $35 billion fix. The reality is closing a gap of this magnitude requires a systematic approach that finds multiple ways to save the whole. That framework should rest on four pillars:

- Operations: Scrutinize every operating assumption and decision to understand how it drives operating cost and capital requirements

- Design & Engineering – Evaluate and question how operating assumptions and design standards drive up project costs AND their impact on the rider experience

- Financial Strategy: Identify financial policies or restrictions that limit financing capacity and develop a strategy to change them

- Federal Strategy: Activate allies to minimize federal regulatory risk

Before cutting scope, Sound Transit must exhaust reversible operational, design, and financial decisions that can close the budget gap without eliminating stations or lines.

Start with operations: The foundation of cost

Operations is the foundation and everything that follows these decisions. Seemingly mundane policies — fare policy, train frequencies, and rail car design — have enormous implications for both operating and capital budgets.

Sound Transit projects a systemwide farebox recovery of roughly 15% over the life of its plan. Large U.S. transit agencies typically recover closer to 35%1. Getting to 30% (close to industry norm and Sound Transit’s pre-COVID level) could close more than $5 billion dollars of the funding gap — and the policy decisions to get there are two-way doors. This is not an engineering constraint; it is a policy choice.

Sound Transit’s plan assumes 6-minute (or better) headways on all three lines for the entire length of the line (e.g. Tacoma to Ballard, Everett to West Seattle, and Redmond to Everett). At very high frequencies, small increases in operating costs are very expensive. An operating plan that is based on actual ridership patterns, with small reductions in frequencies in peak frequencies and matching service levels to demand could save ~$1 billion by reducing the number of rail cars needed to serve the peak period and close to $100 million of dollars per year in reduced operating expenses

The tradeoff is more crowded trains.2 However, this tradeoff can be mitigated with improved train design, a change Sound Transit is already considering that could increase capacity by 5% to 13%.

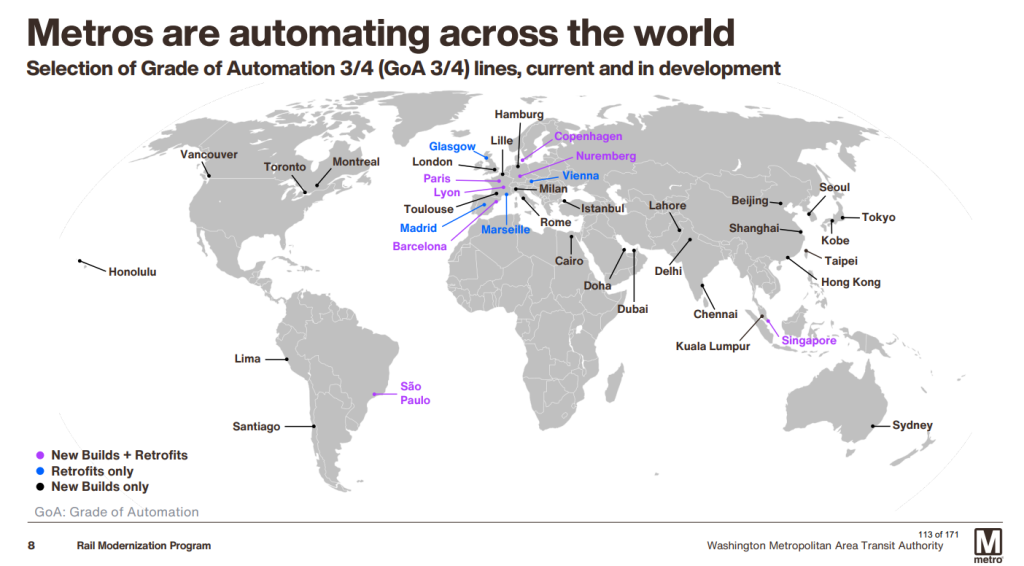

Automation belongs in this discussion as well. Train operators and the administrative staff that support them account for ~12% of light rail operating expenses (~$4.5 billion).3 Additionally, by decreasing the cost of providing service, it is feasible to provide more frequent service across all hours. What’s more, eliminating the remaining driver cabs (and the improvements above) increases rail car capacity by 10% to 25%.

The tradeoff on this is clearly political and human, lost union jobs on the one hand and more ubiquitous, frequent transit for all workers on the other. The Board should be directing the staff to automate as quickly as possible, and simultaneously develop a strategy to assist impacted employees. Systems all over the world are building new and retrofitting old lines to automated operations. This is a policy and planning question, not a fantasy technology.

Taken together, fare policy, frequency, automation, and train design can save billions in operating funds and set the stage for saving hundreds of millions more in capital savings by purchasing fewer, better rail cars. All without meaningfully degrading the rider experience relative to the alternative: permanently eliminating stations, truncating lines, or delaying service for decades..

Design and engineering: Conservatism has a price

Once operating assumptions are set, they cascade into design decisions — often invisibly. Elected leaders and executives are taught to set a vision and empower their technical staff to execute. Questioning technical staff is viewed as “getting in the weeds” and micromanaging. But a $35 billion cost overrun in an industry that consistently underperforms its global peers calls for the board, executives, and outside experts to dive deep into the weeds. There are countless examples (more than one post can handle) of overly conservative engineering standards driving up costs. Three that jump of the page are: platform level of service, station lengths, and track design standards.

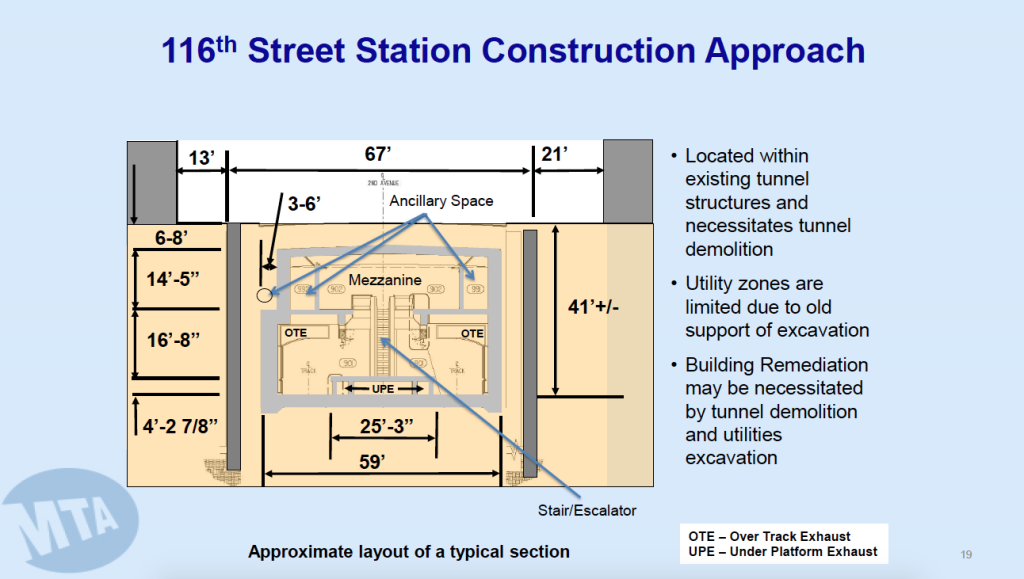

Sound Transit’s platform level-of-service standards call for center platforms roughly 34 feet wide. For context, Washington Metro’s Union Station — more than twice as busy as Sound Transit’s busiest station — has platforms about 30 feet wide. New York’s 2nd Avenue subway is building new stations with a 25-foot center platform (see 116th Street Station diagram above). Many global systems operate comfortably with even less. Reducing platform widths into a reasonable range would significantly cut the cost of excavation, reduce material cost, and minimize surface disruption. The tradeoff is modestly more crowded platforms — not eliminated stations.

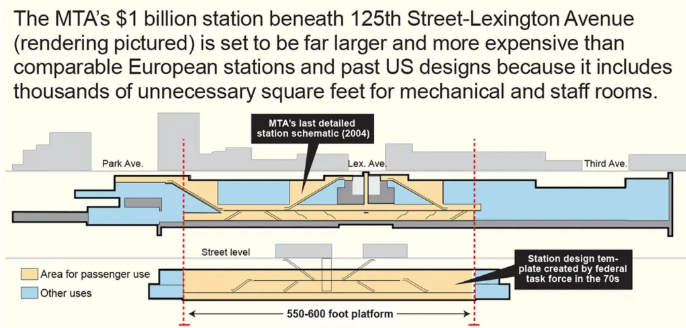

The decision to build deeper, longer, and wider stations (a.k.a. “station bloat”) is well-documented and driving up cost and disruption due to construction. New stations are almost doubling the amount of material excavated (non-platform areas, mezzanines, and back-of-house spaces) with no tangible improvement for the rider. Small reductions in underground footprint translate into hundreds of millions in savings.

NYC offers a concrete example of how station size has metastasized across the U.S.

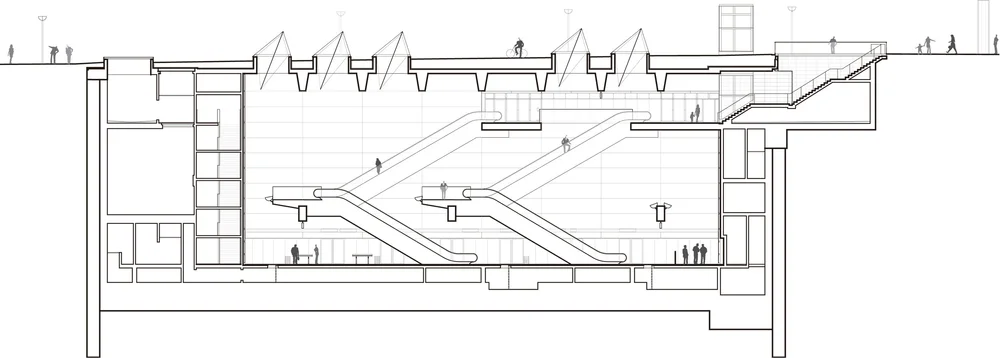

Copenhagen is a great example of how using the vertical space above the platform for vertical circulation to the surface and minimal non-platform space can reduce station size and construction disruption without impacting the rider.

Track design standards are even more arcane, but can be just as impactful – if not more. Sound Transit engineering standards require stations to be built on horizontally and vertically tangent tracks (a.k.a. perfectly straight and perfectly level). When building a brand new station on brand new track this is a reasonable standard. But the Graham Street infill station shows how blind adherence to exceedingly (and needlessly) stringent engineering standards drives up cost when retrofitting existing infrastructure. Building on the existing track is feasible and would meet ADA standards, but Sound Transit has decided that it needs to rigidly adhere to its standard and rebuild the track.

A very telling indicator of “why” is that cost was not an explicit criteria in evaluating alternatives. Once standards require rebuilding track, disruption goes up, new costs start to materialize, right of way (ROW) acquisition increases. This is how an at-grade station balloons to $200 million (for reference the entire Rainier Valley section of Link cost $128 million ($219 million in 2025 dollars). The agency has chosen a path that is almost an order of magnitude higher than simply replicating the station design north and south of Graham Street – a textbook example of letting perfect be the enemy or the good.

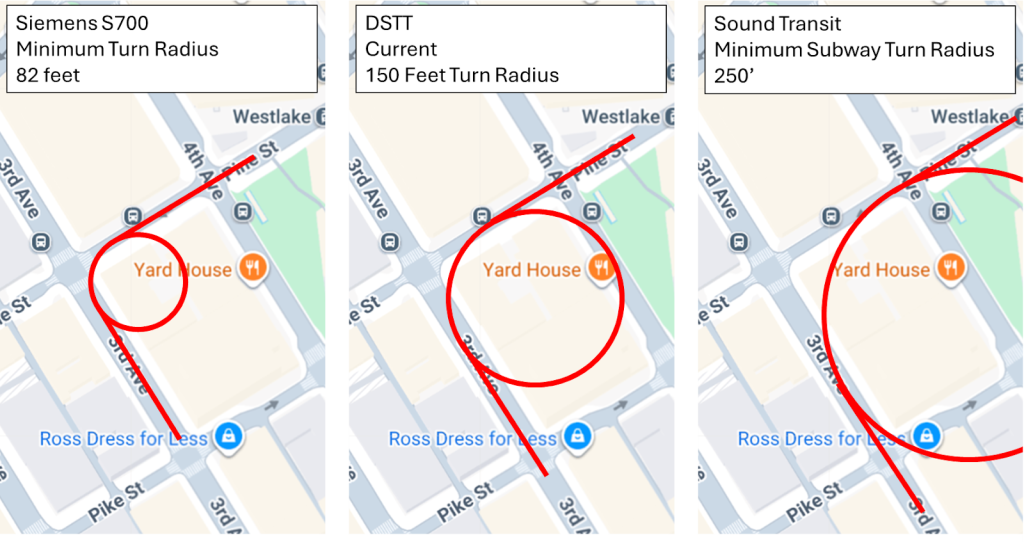

This is to say nothing about the minimum turn radii Sound Transit applies to its track design, which makes cut-and-cover construction impractical without massive right-of-way acquisition cost (example below). Vancouver reduced cost by 16% on the Canada Line changing from deep bore tunneling to cut and cover.

There is no better parallel for Sound Transit’s ballooning costs than the California High-Speed Rail (CHSR) project to show how engineering decisions hidden in plain sight cause costs to balloon. CHSR has updated its Design Criteria Manual adopted a design speed 30 mph faster than CHSR trains’ maximum speed, grade requirements for freight rail (vs. lighter commuter rail), and vertical clearances almost 70% taller than the clearance required by their vehicles. These all contributed to ballooning costs for “tunnels, bridges, and associated earthworks — which together account for more than 50% of the project’s capital costs.” Luckily, their new CEO has identified the problem and is moving to fix it.

Train design, platform width and length, and track design are the tip of a very large iceberg of cost savings that have de minimis impact on the rider experience. Strict adherence to level of service (LOS) and design standards has driven highway design to the detriment of communities for decades. Sound Transit is applying the same logic.

None of this argues for unsafe or substandard infrastructure. It argues for aligning Sound Transit’s design standards with global peers, rather than treating gold-plated assumptions as immutable facts. Dow Constantine should demand the same depth of review for Sound Transit’s design standards.

Financial constraints are not immutable laws of physics

Even after operational and design reforms, the gap won’t disappear entirely. That brings us to financing. The Board needs to request a financial plan that fully closes the funding gap.

Some limits are statutory. Others are self-imposed. Treating both as immutable creates unnecessary constraints. Sound Transit should examine state law that currently limits Sound Transit’s borrowing capacity to 1.5% of the assessed value of the transit district. Right now, property tax accounts for 6.5% of all revenue, excluding federal grants, but this borrowing restriction is driving down agency financing capacity.

This isn’t the 11th commandment Moses brought down from the mountain. It is a law that can get changed by the state legislature OR the voters. Asking voters to allow Sound Transit to borrow slightly more seems lower risk and allows ST4 to be a vote for expansion vs. filling holes.

The Board should also explore its current debt policy on coverage ratios and cash reserves. The tradeoff here is Sound Transit bond rating – currently AAA. The approaches above would likely lower ST’s bond rating – potentially raising borrowing cost. The funny thing about a bond rating though, it is only worth having a good one if you borrow money. There is a balancing act between financing good public investments and maintaining a strong credit rating.

Ironically, Sound Transit’s credit rating may not have a huge impact on borrowing costs. Much of the agency’s borrowing comes via the federal TIFIA loan program. The TIFIA loan program offers borrowers the same rate regardless of bond rating because it is backed by the federal government. The only stipulation is that the revenue stream must be “creditworthy” or investment grade (rated BBB or better by a major credit agency).

The current notion of a 75-year bond should be a last resort. First, it is bad financial policy – particularly with current interest rates – the loan term exceeds the useful life of the asset its financing. Money that should be used to rehab the system in the future will instead be used to finance the initial investment. Second, the cost of the additional capacity is exorbitant. Over the life of the loan, Sound Transit will pay 2.5 to 3 times more interest (depending on rates) on a 75-year loan than it would on a 35-year loan (the standard TIFIA loan term). This is VERY expensive debt.

Staff needs to show the board how changing current constraints creates financial capacity to close the remaining gap and transparently discuss the tradeoffs with the board.

But delay…

The biggest risk of delay is federal approval of Sound Transit’s environmental impact statements (EISs) for its respective projects. It is important to remember the purpose of the EIS: document environmental impacts. What’s more, many of the changes (higher capacity trains; smaller, less intrusive stations; less disruptive track work; less property takings) will reduce the environmental impact.

There is ample time to redesign smaller stations before they become “critical path” schedule drivers. The tunneling can begin and will be far from completion by the time Sound Transit has new, more cost-effective stations designed, all without impacting the overall schedule. This requires a change to how Sound Transit contracts for construction and to accept certain constraints on future station design.

All of the changes above fall under the umbrella of “value engineering.” They reduce the environmental impact, fall well within the scope of a supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), and can be addressed in a matter of months not years.

If the Federal Transit Administration holds up these changes and requires a new full EIS, the Sound Transit CEO and Board needs to activate their federal allies. That means U.S. Senators Maria Cantwell and Patty Murray and the Puget Sound delegation in the U.S. House. It also means the delegates where steel rails will get rolled, rail cars will get built, and other components are built (a classic Department of Defense / military industrial complex strategy).

None of this eliminates federal risk, but the alternative, cutting lines and stations, is not risk. It is a certainty.

A better way forward

Before eliminating a single station or truncating a single line, the Sound Transit Board should publicly answer four questions:

- Have we exhausted reversible operational and policy changes before making irreversible cuts to scope?

- Are Sound Transit design standards aligned with global best practice — or with institutional conservatism, and does Sound Transit have a process for deviating from them when it makes sense?

- Have we tested every financial assumption and constraint to show what COULD be if we approached state law and board policy as mutable?

- Has Sound Transit developed a federal strategy to deal with funding and environmental delay?

If the answer to any of these is no, then cutting or deferring scope is premature.

This region does not lack money so much as it lacks a framework and a strategy. A $35 billion gap cannot be closed by hope, future ballot measures, or piecemeal reductions. It can only be addressed by disciplined, systems-based, and rider-focused decision-making that treats cost, capacity, and credibility as inseparable, and improving delivery today will ensure that voters clamor for an ST4.

Sound Transit owes voters — and riders — nothing less.

Foot Notes:

1. Farebox recovery is driven by a combination of ridership, system design, pricing, and fare enforcement. From a system design standpoint, Link is much closer to a heavy rail or commuter rail system than a typical U.S. light rail system and are more appropriate peers for benchmarking policy. Sound Transit ridership is quite high, but in the future its typical trip will be very long (more typical of a commuter rail system like Bay Area Rapid Transit). Given its current flat fare, suburban trips on the spine will have much lower cost recovery than short trips in high rider density segments in the core of the system. A different flavor of subarea equity.

2. Sound Transit defines crowded as 4.4 square feet per standing passenger. If Sound Transit adopted load standards comparable to systems like New York City’s subway (3 sq. ft. / passenger), it could increase “capacity” by roughly one-third without building anything new.

3. Sound Transit cost of human operators is opaque as it is partially included in ST’s operating budget as salary and fringe and partly included in Purchased Transportation from King County Metro. Using 2024 numbers (most recent available), the cost per hour is $664, assuming a typical operator wage of $37 and a 42% fringe rate; the direct cost of operators is about 8%. The county budget is opaque and doesn’t transparently present salary, fringe benefits, and overhead costs (supervisors, HR, etc). It is not clear what overhead rate Metro applies. This old report indicates that it is likely around ~40% to 50%, bringing the cost of human operators to about 11% to 12% before considering any ST operator-related costs

Scott Kubly

Scott Kubly was the Director of the Seattle Department of Transportation under Mayor Ed Murray from 2014 to 2017. Prior to SDOT, Scott held senior leadership roles in the Chicago DOT and Washington DC DOT. He also led a team of Office of Management and Budget analysts for Mayor Adrian Fenty in DC and worked for the Washington Metro (WMATA) for five years leading capital financial planning strategy.