The agency is squeezing riders who take short trips to subsidize long rides and a suburb-focused service profile.

Sound Transit is poised to implement flat fares for its light rail network, and while the agency paints the changes as user-friendly, most riders will experience the change as a 30% fare hike. Beyond the sting of higher fares, a flat fare structure also reveals that a suburban vision is guiding the agency, which could queue up yet more blunders in the future.

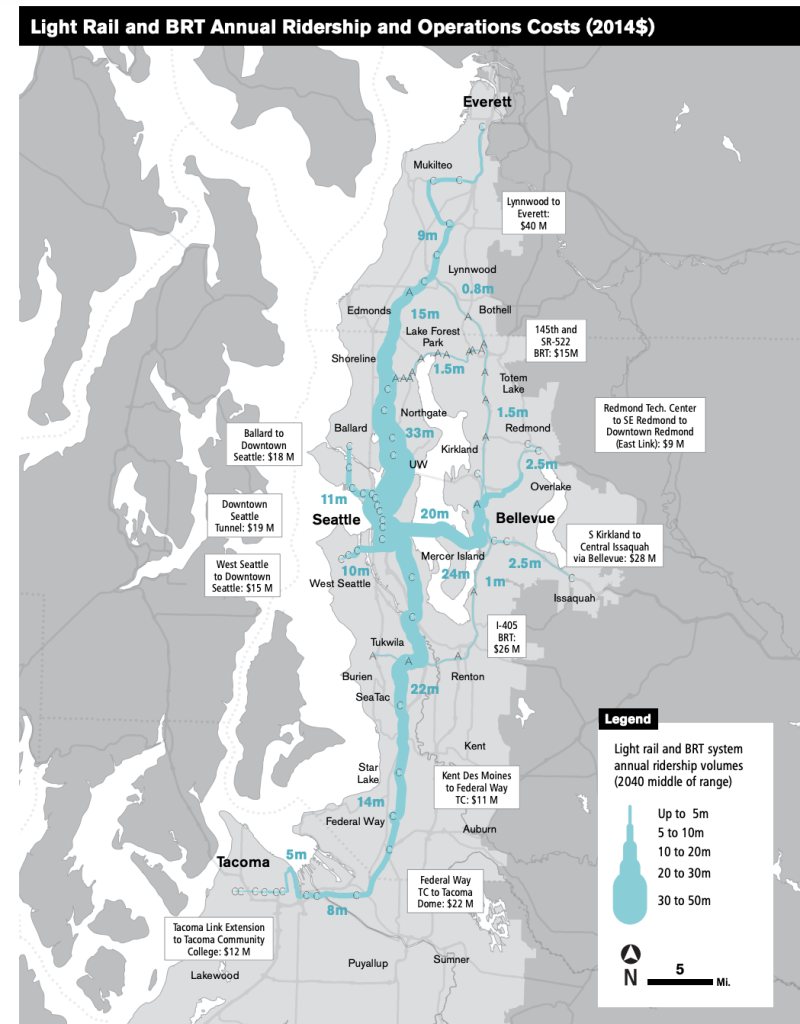

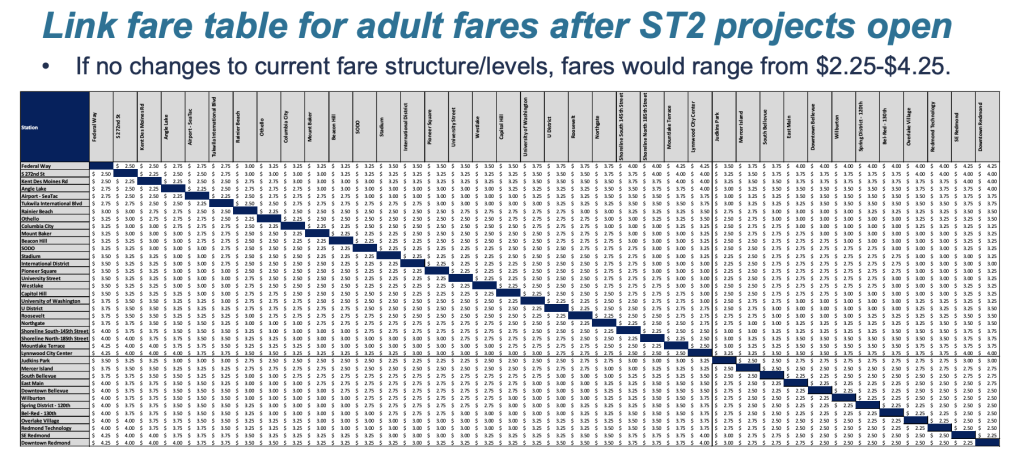

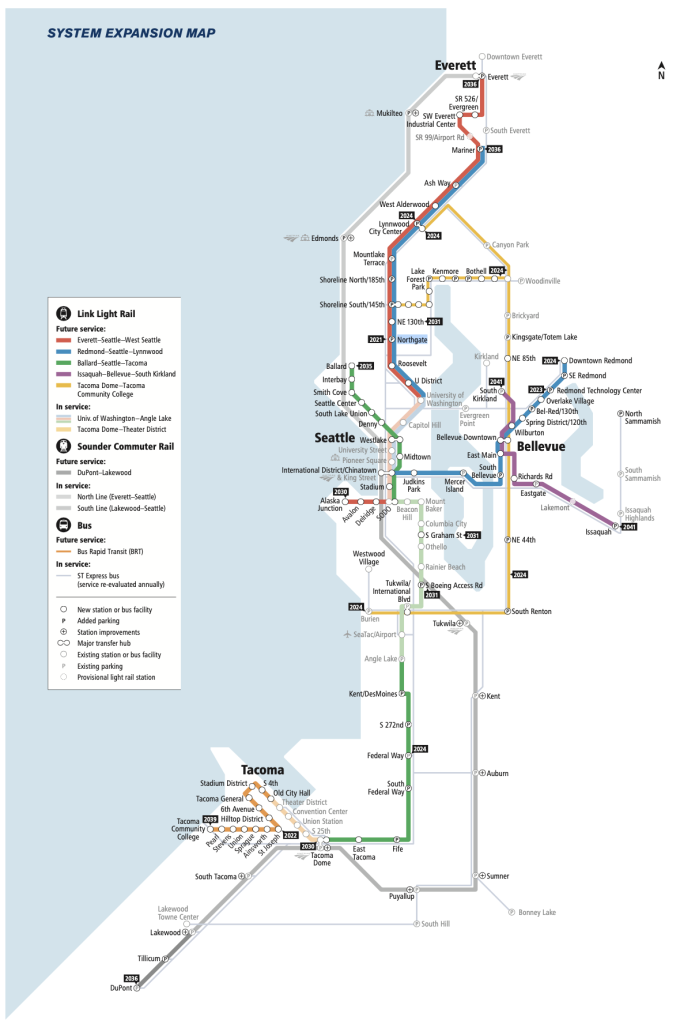

Initially, a flat $3.25 fare might not seem like a big deal, but as the system expands it will become increasingly absurd. Sound Transit’s main goal has been to “complete the spine” to operate a 62-mile long light rail system spanning from Tacoma to Everett. Flat fares mean a rider deciding to ride 62 miles from end to end would pay the same as a rider only going a couple miles from UW to Capitol Hill or Rainier Beach to Columbia City.

A rider going dozens of miles strains the system much more than a rider going only a couple of miles. The beauty of getting off after a couple stops is that it makes space for somebody else to get on. However, riding the whole length of a line is the most taxing kind of trip that eats up system capacity and drives up operational costs.

The logic of distance-based fares (like Sound Transit has now) is that long-distance riders should pay more because the operational cost of serving this kind of trip is higher. It’s a simple way to reflect the cost of a service in its price and it has the benefit of reinforcing the decision to live close to work or school, which lessens strain on the transportation network across the board. Instead, we are left with the opposite signals, where riders are disincentivized from taking short trips — the bus would be cheaper — and encouraged to take long trips.

That incentive to take long trips comes with a hidden cost. It means trains are more likely to be full by the time they reach the busiest nodes of the system. Due to failure to plan sufficient system capacity to deliver promised train frequencies, Sound Transit has warned that crowding will be an issue, particularly in the highest demand areas between Northgate and SoDo. In effect, riders in the core will be left paying significantly more for worse service.

The overwhelming majority of ridership will be in the core of the system, with a healthy dose of short urban-hop trips fueling that ridership. This leads to another issue with flat fares: It puts the rider incentive where demand is weakest and maximizes the disincentive where demand is strongest. Even slashing fares, there’s only so much potential to entice trips on the edges of the network. As a result, the flat fare structure is a recipe for weaker ridership.

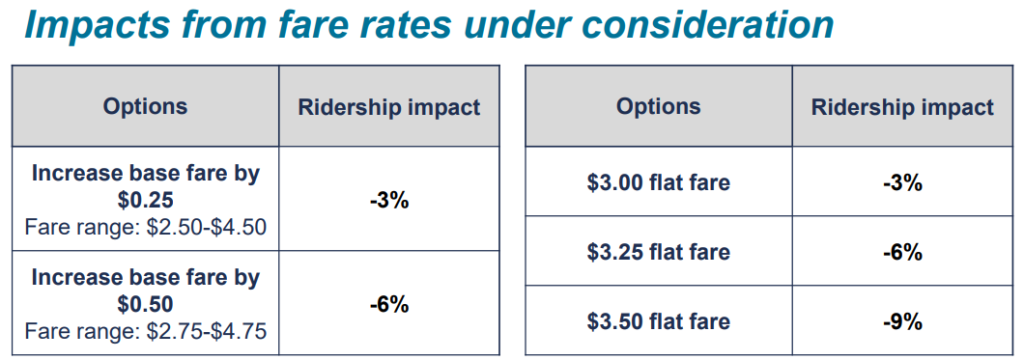

This is backed up in the agency’s own analysis and public outreach, with a greater portion of respondents saying flat fares would discourage them from riding versus entice them. Sound Transit projects a $3.25 fare would lead to a 6% reduction in Link ridership, which the agency has deemed a “minimal impact.” Meanwhile, raising fares by $0.25 in the existing distance-based system would reduce ridership 3%, according to agency projections. Fare simplification is coming at the expense of ridership.

It’s not just Seattle riders who are likely to take short Link trips. The jobs and amenities clustered in downtown Bellevue are going to encourage Eastside residents to ride East Link a few stops and Bellevue’s growth strategy is also centered in the light rail corridor, amplifying the effect. Those trips would be at or near today’s $2.25 base fare (or $2.50 with a proposed fare hike), but flat fares would take it to $3.25. Even if a Bellevue resident rides into Seattle to the stadiums or downtown, since the trip is relatively short, they would pay less under a distance-based fare.

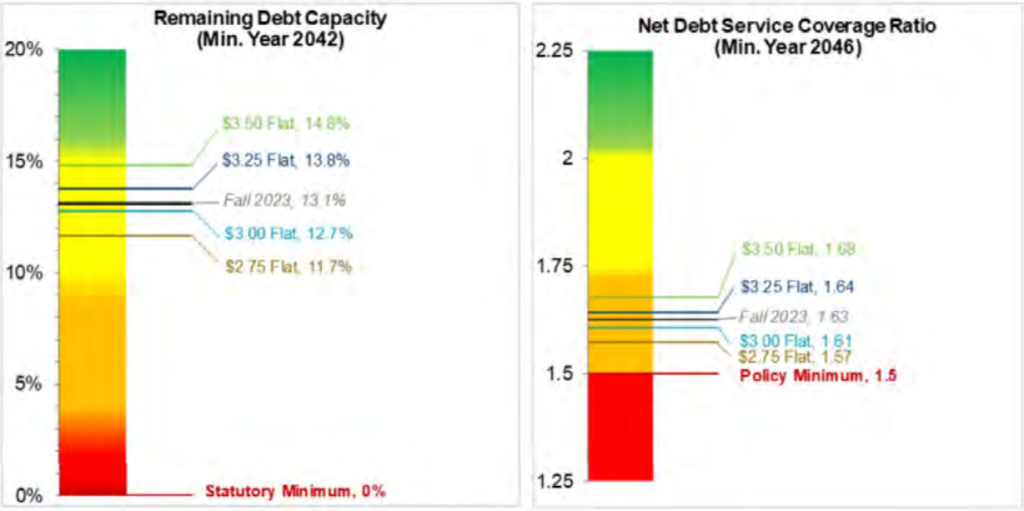

As the system expands, operational costs will increase and fares will need to be raised again — unless Sound Transit reworks its financial plan (by adding other revenue sources or delaying or downsizing projects) and slashes farebox recovery ratio targets. A higher flat fare will be even harder on short trips that only span a few stations. Those short trips are key to meeting ridership projections and supporting transit-oriented development. Leaders have entirely oriented regional growth plans around encouraging people to live near rapid transit stations so they can use light rail as a primary way of getting around for trips short and long.

High flat fares, however, send a signal that light rail isn’t designed for short trips. It’s designed for long-distance suburban commuters.

It’s a conundrum that gave many transit advocates pause when policymakers hatched Sound Transit 3 (ST3) plans in the first place. Link light rail was trying to do it all, spanning 62 miles like a commuter rail line while also offering frequent service in the highly populated urban core like a metro. Because those different identities were contained within the same lines, tension between long-distance commuters and short urban metro hoppers is inherent and having it both ways is nearly impossible.

Many transit agencies have grappled with the challenges of creating a fair fare policy. There is no one-size-fits-all solution since every transit network is different and every structure has tradeoffs. However, several leading systems that are similarly expansive to Sound Transit have landed on zone-based fares, which achieve some of the simplicity of flat fares with the fairness of distance-based fares, maintaining the incentive to choose light rail for short trips.

Unfortunately, Sound Transit did not even study zone-based fares, which stunts the policy debate that the agency is now having. Agency staff have said they did not study zone-based fares because they felt it was not simple enough and board members were not clamoring for it, like they were for flat fares. A few calls published here at The Urbanist were not enough to win them over.

However, zoned-based fares are much simpler and easier to understand than distance-based fares and the complicated fare charts they entail. A Sound Transit zone-based system might entail maybe six zones maximum and a base fare could cover two zones to avoid the unfairness to those who live on the edge of a zone. The fare chart will be much simpler while still providing an incentive for short trips and more closely reflecting the true cost of service.

Somewhat illogically, Sound Transit has argued flat fares have greater compatibility with fare capping and a vague goal of “regional integration” with other transit agencies’ pricing structures. The key thing preventing fare capping isn’t fare structure, it’s political will. Fare capping is quite possible no matter the structure, as other agencies have proven.

As to regional integration, no fare policy will be perfectly integrated with other agencies because fares are all over the map. King County Metro has a $2.75 flat fare and honors the $8 ORCA systemwide day pass, whereas Pierce Transit charges $2 per ride or $5 for an all-day pass, and Snohomish County’s Community Transit charges $2.50 per ride for local service and $4.25 for its commuter lines — the latter are not on the ORCA day pass. Everett Transit charges $2 per ride. Sound Transit’s Sounder commuter rail service ranges from $3.25 to $5.75 based on distance. That $5.75 fare is for the Lakewood to Seattle trip, which will actually be about the same distance as riding end-to-end on the future Tacoma-to-Ballard line. For some mysterious reason, we’re planning to charge a distance-based $5.75 for the longest Sounder trip but a flat $3.25 for Link trips that will be even longer.

The agency should certainly institute fare capping, which helps riders who use light rail multiple times throughout the day by capping the maximum fare charge per day, week, and/or month. Transit agencies should also offer and promote day passes or week passes on their services as a means for riders with ORCA cards to control their costs. However, such a move is quite possible with distance-based or zone-based fares.

The racial and social equity analysis is also mixed, as agency staff have admitted. Lower-income riders in Snohomish County, Pierce County, and South King County would tend to benefit from flat fares while lower-income riders in Shoreline, the Eastside, the Rainier Valley, and other parts of Seattle would tend to suffer.

The agency’s ORCA Lift reduced fare program blunts the negative impact on the lowest income riders, but regional transit agencies are only about halfway to their goal of 80,000 active Lift passes distributed, which shows many intended recipients are falling between the cracks. And with the qualification threshold set at 200% of the federal poverty line, plenty of people — teachers, social workers, baristas, etc. — remain heavily cost-burdened by transit costs (compounded with the region’s high cost of living) but do not qualify for reduced fares. This is who will bear the brunt of fare hikes.

Torn between suburban and urban service focus, Sound Transit has to choose, and the flat fare debate shows that the board is landing on a suburban vision. Recent decisions to spend $360 million building Sounder parking garages or to consider canceling an entire station in fast-growing South Lake Union to cut costs echo this paradigm as well.

Other decisions compound this error. For example, selecting light rail as the system technology means each train has less capacity than a heavy rail counterpart even though construction costs are similar. This mistake is already rearing its ugly head with premature service capacity issues in a young system. Facing serious overcrowding concerns once Lynnwood Link opens, the agency has balked at instituting turn-back service to boost train frequencies in the crowded core of the system because it would complicate operations and it might seem unfair to the suburban areas at the end of the line.

Newsflash: It’s going to get complicated operating a 116-mile light rail network that is simultaneously trying to act like commuter rail and a metro while seeking to appease disparate factions across the tri-county region. Best get comfortable with complicatedness. The only way to patch together a cogent service pattern is with much more frequent service in the core than in the outskirts and a fair pricing structure.

With mismatched parts and a wandering vision, Sound Transit has the makings of a frankenstein transit system.

Dreams of Seattle growing into a world-class city depend on it having a metro to act as the backbone of the transit network. A functioning metro would allow Seattle to shoulder rapid population growth without trapping residents and workers in gridlock. However, the suburban vision guiding Sound Transit is making it increasingly unlikely that Seattle will ever have that high-functioning metro rail system. The risk of a stunted frankenstein is real.

The hopes of a true metro system rest on Ballard Link, and unfortunately planning isn’t going well at all. So far, the Sound Transit Board has managed to:

- Abandon two of its highest ridership stations — Chinatown and Midtown — while planning a clearly inferior transfer hub station in Pioneer Square.

- Delay the project by four years from an initial plan of opening in 2035 to now 2039 at the earliest due to planning delays and decisions that have ballooned costs without offering a clear path forward.

- Walk away from initial station plans for Denny, South Lake Union, and Uptown stations due to neighborhood and business pushback forcing the agency back to the drawing board to design stations anew at different locations.

- Dwell on reducing construction impacts, particularly for motorists and businesses, at the expense of maximizing ridership or transit quality.

Given the staff recommendation and momentum behind the proposal, Sound Transit appears likely to approve a $3.25 flat fare to be implemented as Lynnwood Link opens in fall 2024. The move goes to the Rider Experience and Operations Committee tomorrow (December 7) and may get a final board vote as soon as December 15.

The agency has even won several leading transportation groups over to the flat fare idea, with Transportation Choices Coalition, Commute Seattle, Move Redmond, and Cascade Bicycle Club sending a letter backing a $2.75 flat Link fare. The agency is unlikely to set the fare that low since it would cut deeply into future debt capacity, but they are likely to spin the letter as support for their higher proposal.

That Sound Transit boardmembers from Snohomish and Pierce counties support flat fares isn’t unfathomable since their constituents stand to benefit most. The support from the King County contingent (which theoretically has the votes to set policy if they ever got their heads together and united) is more head-scratching. Perhaps King County leaders like being a cash cow for a system increasingly oriented to the outer suburbs, but riders might not share the sentiment.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.