The City of Issaquah fought hard to get a light rail station on the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) map, and they’d like to keep it. That’s the position of newly elected Issaquah Mayor Mark Mullet, who is ramping up a campaign to sway board members not to delay or cancel the Eastside’s next planned light rail line.

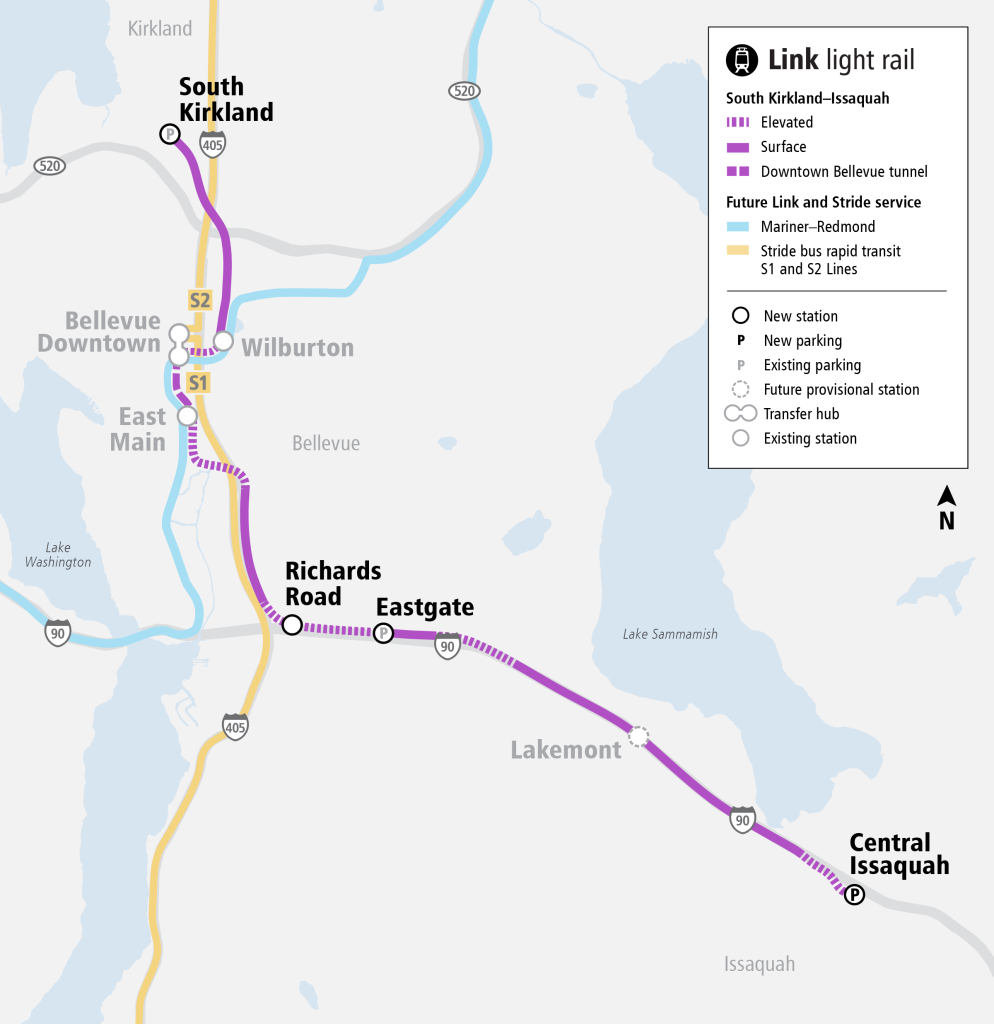

The planned South Kirkland-to-Issaquah Link line would terminate in Issaquah’s underutilized central core, which remains dominated by big box stores and parking lots despite longstanding plans to spur housing growth. The project would connect to the 2 Line in Bellevue via I-90, with two additional stations at Eastgate and Richards Road. A spur north of Wilburton Station would also connect to the South Kirkland Park and Ride, with that entire corridor opening as the 4 Line.

It’s scheduled to be the last light rail project to start construction as part of the ST3 package approved by voters in 2016, with a grand opening date pushed from 2041 to 2044 as a result of Sound Transit’s last attempt to deal with a financial shortfall five years ago.

Sound Transit is now grappling with another financial crisis and working to close a $34 billion shortfall over the next two decades. As a result, Mullet is clearly concerned that the board will turn to the Issaquah line to trim costs. At a meeting Monday night with the Issaquah City Council, he laid out his administration’s approach to keeping things on track, which includes trying to persuade Sound Transit that there are major ways to cut costs that will still allow light rail to come to Central Issaquah, along with what he called a “full court press.”

In addition to hosting a community meeting in Issaquah on February 24, city leaders are gearing up to make a strong showing at upcoming Sound Transit board meetings, including the February 26 full board meeting and the board’s daylong retreat on March 18. At that retreat, the board is expected to start to dig into scenarios that could bring the agency’s long-range financial plan back into alignment.

Originally planned as a $3.3 billion project, the 4 Line has ballooned in cost, along with the rest of Sound Transit’s portfolio, and is now expected to cost anywhere from $5.6 billion to $6.3 billion. While a less expensive line than most of the others planned as part of ST3, it’s also projected to see the lowest number of riders.

Estimates from 2016, likely somewhat outdated at this point, projected 12,000 to 15,000 daily riders using stations between South Kirkland and Issaquah, compared to 37,000 to 45,000 riders between Lynnwood and Everett and 25,000 to 27,000 between West Seattle and Downtown, confirmed in that project’s recent environmental review.

“My whole focus here is to try to approach our light rail segment very differently than, I think, a lot of other communities, where a lot of different segments are asking for changes that drive up the cost and make it a little more complicated. And we’re trying to do the opposite. We’re trying to find suggestions that actually lower the cost and make it easier to build,” Mullet told The Urbanist.

Before being elected Issaquah’s Mayor last fall after a failed gubernatorial run in 2024, Mullet had previously served on the Issaquah City Council from 2009 to 2012 and then served 12 years in the Washington Senate. While his time in the Senate earned Mullet animosity from many of the region’s progressives, support for bringing Sound Transit to Issaquah has been a through line in his career. In 2016, he defeated an anti-light rail challenger for his Senate seat at the very same election that voters approved the overall ST3 package.

Mullet laid out three potential strategies that could gain cost savings for Issaquah Link: ditching any new parking garages, maximizing the amount of the line that lies within WSDOT right-of-way, and optimizing the connection to the existing 2 Line around South Bellevue. He also sees the stop at Richards Road as something that could potentially be dropped, much like a provisonal stop at Lakemont that is unlikely to be built anytime soon.

“I think we’re making an argument, as we met with Julie Meredith, the head of WSDOT, that you could run a line basically using almost exclusively the WSDOT right-of-way,” Mullet told the Council Monday. “And so you’d have to figure out where it ends, but if you’re going to end on WSDOT right-of-way, it’s very likely in the middle of I-90 with some sort of pedestrian overpass. And then you would have a stop at Eastgate, and then you could connect to Bellevue at what is the most cost efficient connection point, which we think would be South Bellevue, most likely.”

Sound Transit’s preliminary design does not interline with South Bellevue Station due to difficulty with the soil conditions and geometry in the Mercer Slough area. Instead, East Main would be the where the Issaquah line ties in to 2 Line, under the agency’s concept, which Mullet appears to be second guessing.

An I-90 median station has a clear precedent in Judkins Park and Mercer Island Stations, but is a harder sell for riders who might not like waiting for a train in the middle of a highway, and leaves out the potential for a station truly at the heart of a walkable neighborhood. But in addition to potentially being cheaper, Mullet painted a median station as providing equal access to the areas both north and south of the highway, long primed for redevelopment.

“I think our vision is that you have a walkable, vibrant retail village, that you can just get on transit,” Mullet said. “But it’s also on both sides of I-90, north and south. We feel like this pedestrian overpass is a way to kind of help connect both parts of town. Right now I-90 is like a river that runs through us, so this is a chance to kind of bridge that divide.”

When it comes to the low ridership forecasts, Mullet pointed to two ways that those numbers could be improved: bringing in riders from elsewhere in the Snoqualmie Valley via feeder bus service, and improving land use in Central Issaquah, which has been a longstanding goal of the city under multiple mayors.

Mullet’s proposal to go all-in in support of Issaquah Link went over well with the city council Monday.

“I will let you know I am thrilled with this approach,” Councilmember Barbara de Michele said. “I think there’s been, in my opinion, there’s been a little bit of mixed messaging coming from Issaquah, and I think that making a forceful statement in that we are here to support this light rail station is really, really important right now.”

During last year’s campaign to lead the city, Mullet touted having worked to bring light rail to Issaquah with former Mayor Fred Butler, the longtime chair of the Sound Transit board’s Capital Committee, which was later renamed the System Expansion Committee. He sees the connection from South Bellevue to Central Issaquah as separate from the spur to South Kirkland, which falls well short of all of Kirkland’s growth centers due in part to local opposition to utilizing the Cross Kirkland Corridor, a rail-to-trail corridor that could have been an economical route.

“I was in this fight way back in 2015, 2016. We weren’t on the map,” Mullet said. “We went to bat for the Issaquah line. They ended up adding in the South Kirkland portion, but our fight was always: we just want to connect to this network. That was our fight, and that’s our still our focus right now, and the Bellevue to Kirkland connection is more challenging, I think, than our connection is, and we don’t want to have that delay our connection.”

Rather than familiar moves to cut segments of lines and delay projects, Mullet hopes that light rail to Issaquah can turn into an opportunity for Sound Transit to get creative about delivering the types of transit investments that cities around the region are clamoring for.

“I am fully aware that they’ve got a budget challenge. I want to help them solve their budget challenge by coming up with ideas to build our line substantially cheaper than what they’re currently estimating, not by having our line removed,” Mullet said. “I’m a big believer that light rail can transform communities in a positive way. I do not have that same conviction that bus rapid transit brings the kind of investments we’re hoping to see. And I think that this is why I’m so committed.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.