The Seattle Social Housing Developer is riding high after receiving news that its recently voter-approved “excess compensation tax” smashed projections and pulled in $115 million in its first year. Social housing advocates’ priority bill at the state legislature is also making significant progress.

The state House passed House Bill 1687 on February 10, and the Senate housing committee advanced the bill with a do-pass recommendation on Friday. The bill grants social housing public development authorities (PDAs) like Seattle’s additional powers and avenues for collaborations with state and local governments under the Housing Cooperation Law.

Earlier this month, the Seattle City Council unanimously passed the interlocal agreement for the disbursement of the funds from the City to the Seattle Social Housing Developer (SSHD). That gives the developer the funds it needs to begin purchasing properties and fulfilling its mission of delivering affordable housing using a new mixed-income model.

House Our Neighbors, the advocacy nonprofit behind the ballot measures, hosted a summit on February 11 to celebrate their progress. Speaking at the event, Seattle Mayor Katie Wilson stressed the importance of taxing the rich to invest in social infrastructure.

“This city is filthy rich. There’s a lot of wealth here. There’s a lot of money here,” Wilson said. “We continue to have one of the most regressive tax systems in the country, in the state, and it is very gratifying to know that we’re going to be able to use a little bit of that wealth and put it to work building housing.”

The excess compensation tax levies a 5% tax rate on companies for the portion of annual compensation that exceeds $1 million per employee. Clearly, Seattle had more high earners pulling in more than a million in compensation annually than the City’s budget office had projected. Officials have cautioned that the tax will fluctuate significantly year to year, with spikes in the stock market driving up revenue, and crashes doing the opposite.

The spate of news is a welcome sign of a momentum for a fledging agency that just went through a major leadership shakeup. In January, the SSHD board’s ousted former CEO Roberto Jimenez, citing frustration with his leadership style and alleged refusal to relocate to Seattle from California. As interim CEO, the board appointed Tiffani McCoy, who left her post at co-executive director of House Our Neighbors.

McCoy lacks development experience, but she has pledged to surround herself with people who do. She is trusted among social housing advocates after leading campaign victories.

As an organizer herself, Wilson noted that grassroot organizing spearheaded by House Our Neighbors led to this victory — not leadership from establishment politicians, who largely opposed the measure at the prodding of the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce. Although she didn’t name names, she alluded to her predecessor and campaign opponent, Bruce Harrell, who became the face of the opposition campaign to the tax measure.

“Seeing establishment politicians line up in opposition to raising progressive revenue for mixed-income, permanently affordable, publicly owned housing, while the public overwhelmingly supported it, showed this fundamental mismatch. People saw what was needed, but a lot of people were committed to business as usual,” Wilson said. “Voters saw through it, and so here we are today.”

Wilson reminded people that the social housing funding measure is what prodded her to run for office.

“This is why I decided to run for mayor,” Wilson added. “One year ago today, I had zero thought in my mind about running for mayor. One year ago tomorrow. I saw the results of Prop 1, and I decided to go for it.”

The shift at city hall was deeper than just Wilson replacing Harrell. Voters sent Seattle City Council President Sara Nelson packing, replacing her with another staunch social housing supporter in Dionne Foster. An avowed centrist, Nelson pushed the chamber-backed alternative measure that sought to sap support from the grassroots social housing measure and her centrists colleagues put it on the ballot. Progressive Eddie Lin also replaced centrist appointee Mark Solomon, giving social housing another friendly vote.

As a result, social housing received a much warmer reception at the council when SSHD leaders went to brief the housing committee in advance of the committee vote on the interlocal agreement. It was a public debut for new staff members, including McCoy and Ginger Segel, who SSHD hired to be its chief real estate development officer, bringing extensive development experience with the Seattle Housing Authority.

Social housing growth strategy

At the February 11 meeting, Segel provided the council’s Housing Committee (chaired by Foster) an update on the new agency’s plans. The initial strategy out of the gates appears likely to focus on purchasing existing apartment buildings, taking advantage of a favorable market.

“The market right now for recently constructed apartment buildings is quite good, so we can pick up some buildings at a good price point, and we think the market is going to cycle away from that in the next two or three years,” Segel said. “So we do hope to take advantage of that. You can buy pretty high quality apartment units for about $350,000 to $400,000 per unit right now, whereas to build them is like $650,000 a unit. So we want to take advantage of this kind of dip in the market…”

While SSHD’s strategy is trending toward purchasing recently-built apartment buildings initially, ultimately Segal said that new construction was likely to be key to meeting their goal of providing family-sized housing.

“There’s no getting around the fact that the private market is is building mostly small units,” Segel said. Only about 10% to 15% of the units are two bedrooms or larger in the buildings they’ve considered for purchase, she added.

“We will look for opportunities to combine small units and make them larger,” Segel said. “There might be some opportunity for that, but we are also trying to build a diverse portfolio for people in Seattle that need housing, and so that ranges from small households to big households. We think the majority of the way we’re going to serve family-sized households is through new construction. We’ll do some conversions, but we think mostly we have to fill that void that the private market is leaving of not building family-sized units.”

Segel also shared the income mix that SSHD is considering for its buildings. While SSHD’s charter says buildings should house people with incomes from zero to 120% of area median income or AMI, flexibility exists for how many units at each income band within that larger band. The staff is using a working assumption of 10/30/30/30 mix in their early financial models, as follows:

- 10% of units at 30% of AMI,

- 30% of units at 50% of AMI,

- 30% of units between 50% and 80% of AMI, and

- 30% of units between 80% and 120% of AMI.

Zoning matters

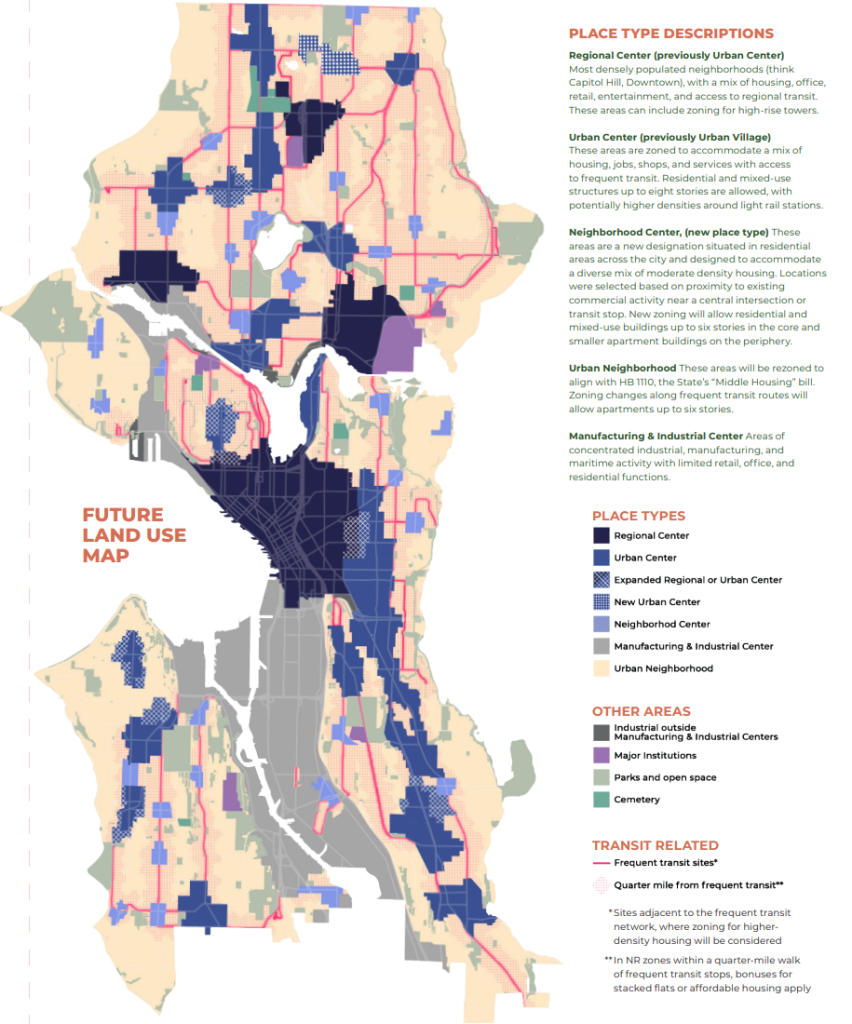

The SSHD also recently hired urbanist and Passive House architect Mike Eliason, who has contributed the articles at The Urbanist as a volunteer. Eliason briefed councilmembers on the SSHD’s thinking about healthier housing, and how the growth strategy in the Comprehensive Plan can be a hinderance on that front.

“With the Comp Plan focus on corridors, how do we site family-sized housing so that kids aren’t growing up directly on roads like Aurora or 15th Avenue NW, broad arterials, high levels of pollution. They’re loud, right?” Eliason said. “So we’re starting to think about how we can site these buildings so that they can be in quieter places, so that they are places that people will want to raise their kids and will want to stay in place.”

To scale up that approach may ultimately require zoning changes. Harrell’s plan limited corridor upzones to the immediate half-block along major transit corridors, and trimmed 50 neighborhood growth nodes proposed earlier to 30. Wilson has pledged to revisit the decision to add more housing density, pending further environmental study that the City legal team has urged.

At the same meeting, Kelli Larsen, Policy and Planning Director with the Seattle Office of Housing (OH) also presented and brought up that just a tiny fraction of land in Seattle has zoning friendly to affordable housing development.

“We’ve looked at a lot of the data and maps and zoning possible for the types of projects that we build, which are typically midrise, and we estimate that we can build midrise affordable housing in about 3% of the city,” Larsen said.

Easing zoning restrictions would create more opportunities for affordable housing projects, and drive down costs for nonprofit builders.

“Zoning really matters, and zoning matters for density and for housing of all types, ” Larsen said. “So, this is a huge part of the housing plan that the Office of Housing does not control, but our partners at OPCD and others in the city are contributing significantly to Comp Plan changes and reforms that are really necessary and significant for the housing market overall. In addition permitting reforms and speeding up the development process infrastructure, all of that contributes to delays that end up costing more and then actual hard costs that add to projects budgets and make them less feasible.”

Rising costs for constructing and operating building has been a growing problem, and increasingly OH has had to dedicate funds to stabilizing finances in existing buildings rather than new construction. Even with those challenges, OH reported 721 affordable rental homes opened in 2025, thanks in part to its funding, including 288 permanent supportive housing units geared toward serving people exiting homelessness.

Larsen sought to correct the notion that there is widespread overbuilding in the affordable housing sector, which stemmed from an August Seattle Times article that cited a point-in-time vacancy rate in the double digits. She said the vacancy rate in OH’s portfolio is around 6%.

“Across our entire portfolio, this is the truth of the vacancy: It is right around 6% right now in the OH portfolio. 7% mean, and our median is actually below 5% — I think it’s 4.7% last we looked,” Larsen said. “So this is much more in line with the citywide vacancy. You know, we’d like to see it closer to three, if we could get there. But it’s not really out of range or out of whack from the way that other units are operating in the city right now.”

Over the last decade, the Seattle metropolitan area has led the nation in affordable housing production, according to figures from RentCafe, although housing leaders acknowledge it’s still far from enough to meet the need.

Looking ahead

McCoy told The Urbanist that the SSHD’s goal is to have its first property acquisition done in the next six months. The interlocal agreement means the social housing PDA will have the money, and Wilson has pledged the support of her administration.

“In a moment when housing costs continue to rise and displacement pressure remains real, social housing is going to give us a tool that can match the scale of the problem,” Wilson said. “My administration is committed to working with the developer, not around it, providing technical support, helping to navigate systems that were not designed for social housing, and clearing barriers rather than adding new ones. Building something new inside existing systems is hard.”

Of course, many hurdles remain and getting the implementation right will be challenging. Wilson ended her speech on a hopeful note and argued Seattle could be a beacon of light guiding other cities struggling to roll out their own social housing regimes.

“We’re going to do everything we can to make the new social hospital developer successful in the years ahead,” Wilson said. “And we also know this work that we’re doing is part of a growing national movement for social housing. Other cities are watching us. They’re watching what we do here. Advocates across the country are learning from us. We have the chance to lead, and not just with ideas, but with implementation.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.