Situated on the central west coast of France, La Rochelle is one of the country’s most popular domestic tourist destinations because of its proximity to Île de de Ré and Île de Oléron, islands best known for their windswept beaches, sea salt production, and pajama-wearing donkeys. However, La Rochelle has also carved out a reputation of its own as a pioneer of forward thinking urban planning and policy.

In a country known for its pride in its cities and urban environment, La Rochelle carries the distinction of being a city of many firsts. In 1970, it was the first city in France to designate its city center as a zone for pedestrians, a move that was quickly followed by enacting some of the country’s strictest historic preservation policies. In 1974 it became the first French city to offer a free municipal bike share program. Those key early decisions led to others later on, such as building out a comprehensive bike lane network, investing in a low emission bus fleet, and fully opening the city center and old port to people walking and biking. A visit to La Rochelle today reveals a flourishing city that is reaping the rewards of those early investments.

When I arrived as a college student in La Rochelle in 2004, I was impressed by how easy it was to walk and bike in the city. At that time, the streets of the city center were open to pedestrians during peak business hours, but the thoroughfare running through the old port was used by cars and buses. But returning to La Rochelle nearly two decades later, the transformation of that street into a space for people to eat, drink, walk, bike, and socialize was stunning. I’d been told in advance to expect the city to be different, but what I hadn’t anticipated was how much more vibrant the public spaces would be at virtually all hours of the day.

Opening streets to people has resulted in many restaurants and shops expanding their footprint. Previously views of the water at the old port were obstructed by moving vehicles, but now it is possible to sit a café and watch people and boats passing by. This is because removal of vehicle traffic created enough space to make possible for a small fleet of ferry boats to come in service linking the city center to the Île de de Ré and Île de Oléron. When I lived in La Rochelle, I only visited the Île de de Ré once because the island was accessible by car or a very long bus ride. The addition of these ferries makes it much more possible for people without a car to move freely between these destinations. Passengers can also bring their bikes on board.

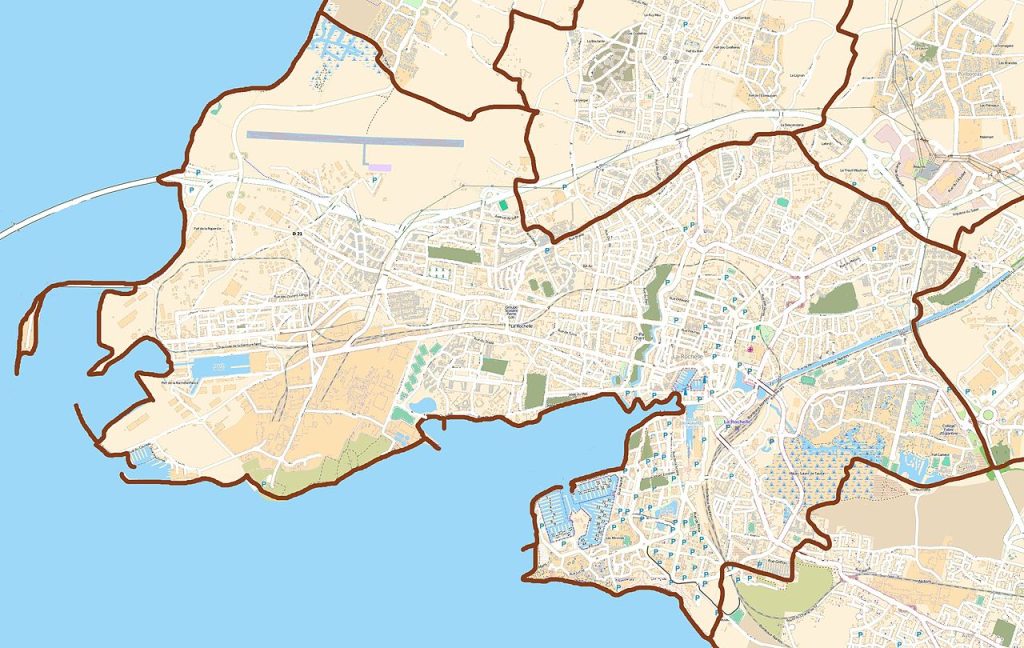

Like many European cities that were spared from World War II bombings, La Rochelle benefits from a compact, walkable center that was designed and built hundreds of years before cities would begin to focus transportation around cars. The city is also naturally flat and hemmed in by coastline that forms a barrier preventing urban sprawl. Some of the city’s most distinctive features today are its urban beaches and its buildings lined with stone arcades, which are very useful in protecting protection against fast-moving Atlantic storms.

But it’s also important to point out, that when La Rochelle did engage in significant urban expansion, starting with the construction of the pleasure port of Les Minimes in the early 1970s, it continued to plan its development around people, not cars. The natural environment was also prioritized in Les Minimes as well, with many trees, grasses, and shrubs incorporated into the urban landscape. A stroll through the neighborhood today shows a modern neighborhood with mid-size residential and commercial buildings connected by sidewalks and bike paths.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that a city needs to be either designed pre-automobile or created as a planned community in order to avoid many of the problems that cars introduce into an urban environment. But Les Minimes shows that it’s possible to create an environment focused on people without entirely banishing cars. Also, by incorporating more greenery and designing streets and sidewalks to be accessible for people with disabilities, it’s possible to create an urban environment that is even more comfortable and welcoming of people than what exists in the historic areas.

Despite its postcard image, La Rochelle is very much a working city with a large maritime industry. Les Minimes is one of the largest pleasure boat ports in the world, and located not far away are shipbuilding and repair businesses. La Pallice, an industrial focused port on the north end of the city is busy with shipping and fishing. From an American perspective, it’s interesting to see how this maritime industry occurs in close proximity to residential areas and cultural destinations like the city library and aquarium. I remember as a student walking back to my university residence at night and staring in wonder at the huge boats under repair.

The presence of industry, along with the university, make La Rochelle a more thriving economic center than it otherwise would be. Housing prices in La Rochelle have been rising in the city recent years, but still remain affordable when compared to the Parisian region or larger cities. A survey of social housing in La Rochelle shows a few social housing developments, known as HLMs in France, located near the old port and Les Minimes, but like much of France, the need for more social housing is on the rise — even as the country remains leaps and bounds ahead of the United States on housing policy. Even with the new development, the city’s population is hovering around 77,000 inhabitants.

La Rochelle is not perfect. Like many French cities with expansive pedestrianized areas, it’s possible to find large surface level parking lots located a stone’s throw away, indicating that cars remain an important part of the regional transportation infrastructure. The same train tracks that connect La Rochelle to France’s extensive regional and national rail network have also served as a barrier isolating the southeast section of the city. However, La Rochelle is engaged in an effort to redesign the train station that includes creating new connections across the tracks for people walking and biking and improving bus connections to reduce the number of cars used to access the station.

The new planning efforts centered around the train station are another example of how La Rochelle firmly keeps its eye on the future. Sometimes it can feel futile to try to reroute the course of development in a city. However, La Rochelle shows that with consistency and dedication to long range goals, it’s possible for cities to use smart policies to continually improve quality of life.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.