Early this year, Minneapolis made headlines when it decided to eliminate restrictive single-family zoning laws citywide. Others followed. Oregon passed a measure that requires cities larger than 10,000 in population to rezone areas for single-family homes to allow duplexes. In Washington, such changes have been attempted in Seattle, Kirkland, Tacoma, and Olympia.

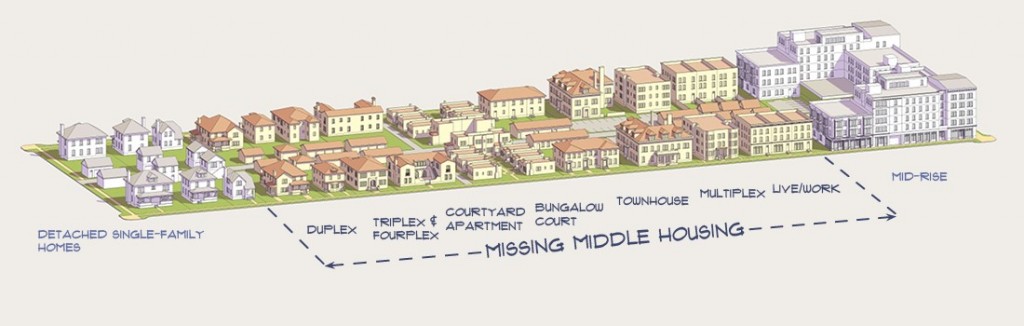

Some advocates want to go further and permit other housing types like triplexes, rowhouses, courtyard apartments, and small condominum buildings–collectively known as “Missing Middle” housing types–in all residential zones. The prevalence of detached single-family zoning has choked this type of housing production. Given our current zoning, rules, and financing structures, developers tend to produce either single-family homes or large apartment buildings and seldom anything in between–hence the Missing Middle moniker–which works doubly since these housing types are a staple for middle class families, providing a more affordable option than single-family homes.

Olympia launched its Missing Middle initiative in 2016, and it is still being debated. Detractors argue that allowing more housing types would actually increase the cost of housing. Jim Keogh, an Eastside resident argued in a 2018 hearing that parking requirements–which are known to increase the cost of housing and put it out of reach of low- to middle-income residents–were necessary, since without them it was too easy to build new housing. The argument being that if it’s easy to build more housing, the price of living in a neighborhood goes up since the neighborhood becomes more attractive for developers.

At play is a key misconstruing of microeconomic and macroeconomic principles. One group is claiming that microeconomic impacts, such as construction of new housing, will lead to unaffordability as new amenities in the neighborhood increase the desirability of houses next door. The other group is claiming that more housing availability will ease the burden on the region, allowing housing growth to keep pace with job growth.

Each side has a point. However, what detractors in their microeconomist pose fail to see is that such “upzoning” simply makes single-family neighborhoods subject to the same natural market forces that all other neighborhoods have always been subject to. Gentrification, for decades, has largely been a concern in urban, longer-established neighborhoods. These neighborhoods were never given the same protections that their low-density single-family counterparts were, and those residents, who are and were disproportionately people of color, took on the burden.

Historians have noted that single-family housing has its roots in racially motivated exclusionary housing practices–single-family zoning zoning spread as racial covenants and other discriminatory practices were struck down. That’s not to say that all opponents of Missing Middle housing today are motivated by race, but the ability to “preserve neighborhood character” through a regulatory framework is a privilege long only afforded to wealthier and disproportionately white residents.

We should have made Missing Middle zoning changes 20 to 30 years ago, across the country, before cities such as Washington, D.C flipped from 70% African American to 45% in just twenty years. Cities are playing catch up. As a region, the Puget Sound has experienced 16% job growth since the recession, and only a 9% increase in households. Most housing growth–especially working class housing growth–has occurred on the periphery, increasing traffic and putting a strain on our resources.

To those who are opposed to Missing Middle housing, yes, this will bring change to your neighborhood. Ask yourself though, is it fair that certain neighborhoods can suppress change while others cannot?

In January, a group of Olympia residents challenged the city’s Missing Middle ordinance to the state’s Growth Management Hearings Board. In July, the board ruled that the city could not implement Missing Middle housing on concerns unrelated to those most often stated by its opponents. It ruled that the city did not thoroughly comply with State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) regulations and that the proposed parking reductions for Missing Middle housing were too great and did not reflect the city’s comprehensive plan. In the November 2019 election, pro-Missing Middle candidates won by substantial margins. And now the city council plans to re-submit its plan to the Growth Management Hearings Board in 2020.

Andreas Wolfe (Guest Contributor)

Andreas is an urban planner and transportation engineer currently based in Olympia, Washington. He graduated with a dual masters in planning and civil and environmental engineering from Georgia Tech in the Spring of 2019, and has since worked as a long-range planner for the Washington State Department of Transportation. He is a 2019 US DOT Eisenhower Fellow, awarded for his work on route planning and administration of county-run rural transit in the US State of Georgia.