America’s most regressive social policy has entrenched the racial wealth gap. It’s time for it to go.

This article is the second half of a two-part series on the importance of ending the Mortgage Interest Deduction (MID). Part One focuses on how the MID works and what negative effects it has had on society at-large.

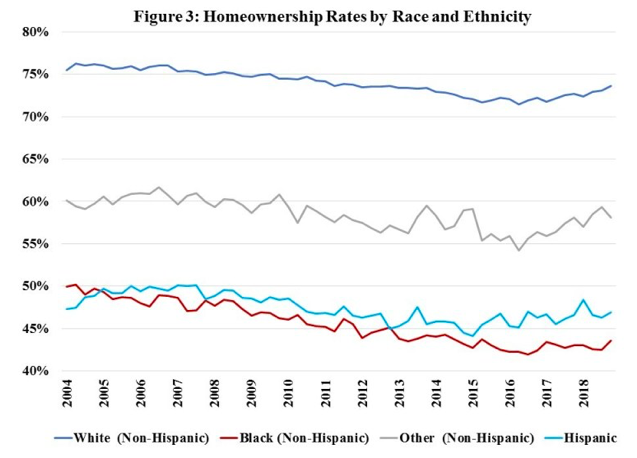

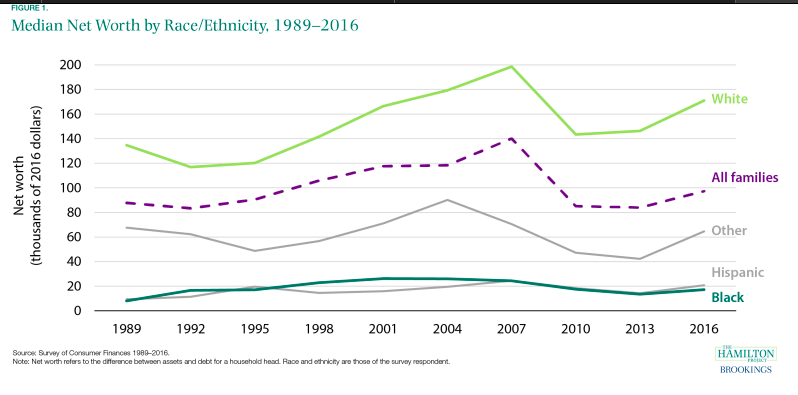

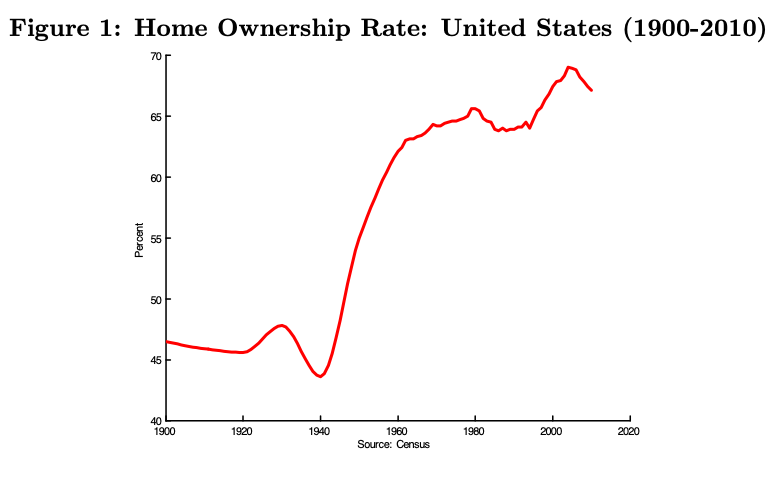

As long as you have set foot on American soil, in one way or another you have experienced the nation’s glaring racial wealth gap. Still there are statistics that bear repeating. According to a recently published report from Brookings titled “Examining the Black-white wealth gap”, the economic disparity between black and white Americans is greater now than it was a century ago. Furthermore, at roughly 41%, black homeownership is at its lowest rate since since 1950. Factors like income and educational attainment have contributed to the wealth disparity, but they do not explain the full extent.

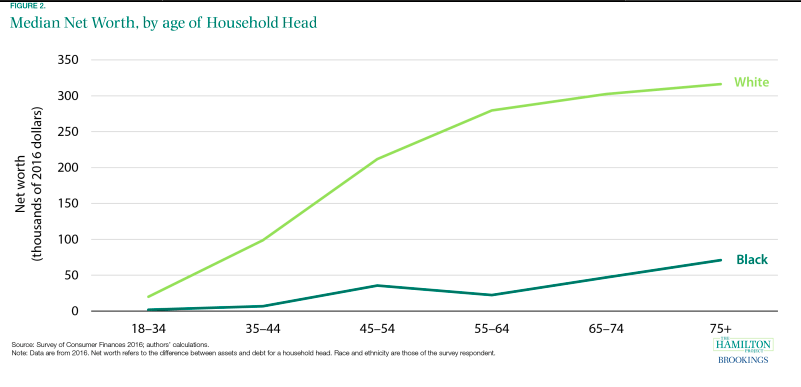

Where then do we lay the blame? Economists Darrick Hamilton and Sandy Darity, who have promoted the creation of Baby Bonds, a program which would increase economic mobility by giving every American child an interest-bearing savings account at birth, have concluded that intergenerational transfer of wealth “account[s] for more of the racial wealth gap than any other demographic and socioeconomic indicators.”

White households are twice as likely as black households to receive an inheritance. Moreover, receipt of an inheritance is associated with a $104,000 increase in median wealth among white families, but only a $4,000 increase among black families.

“Exploring the Racial Wealth Gap Using the Survey of Consumer Finances.” (2015)

Amending the estate tax would be one important way to address this issue. However, in 2019 estate taxes, along with gift taxes and customs taxes only comprised about 5% of the federal government’s revenue, a percentage that has not budged much since the 1950s.

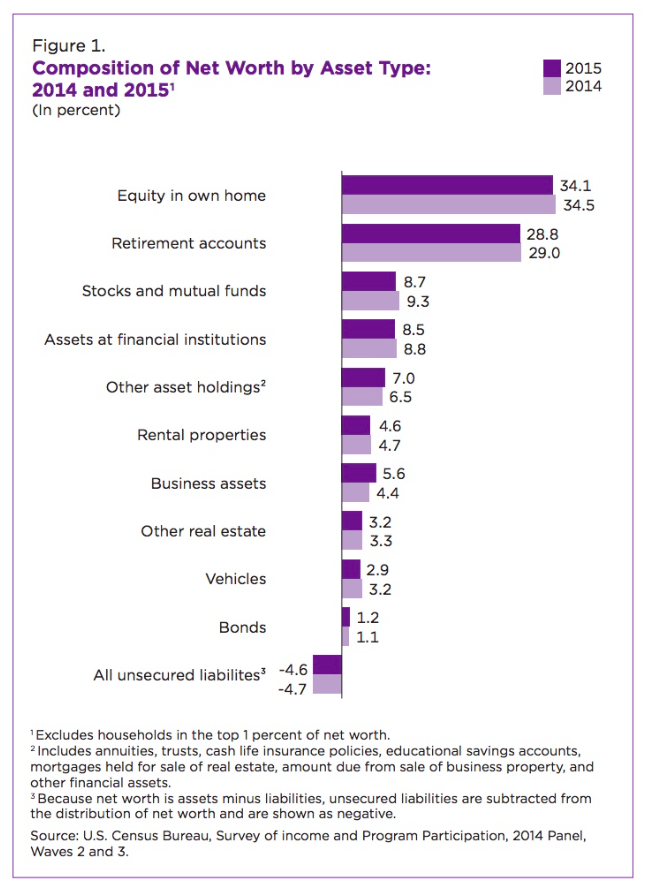

When discussing the intergenerational transfer of wealth in America, it is important to reference the crucial role that homeownership has played in wealth building for many Americans. Homeownership is more than the cornerstone of the mythical American Dream, it is the primary means by which Americans gain and pass on their wealth; on average the net worth of a homeowner is 80 times greater than that of a renter. Why is it then that the federal government continues to spend billions dollars annually subsidizing homeownership for wealthy Americans through the Mortgage Interest Deduction (MID), yet does virtually nothing for renters and lower income homeowners?

The origin of the racial wealth gap lays in 250 years of slavery, but economic and social racism from the 20th century to today continue the disparity.

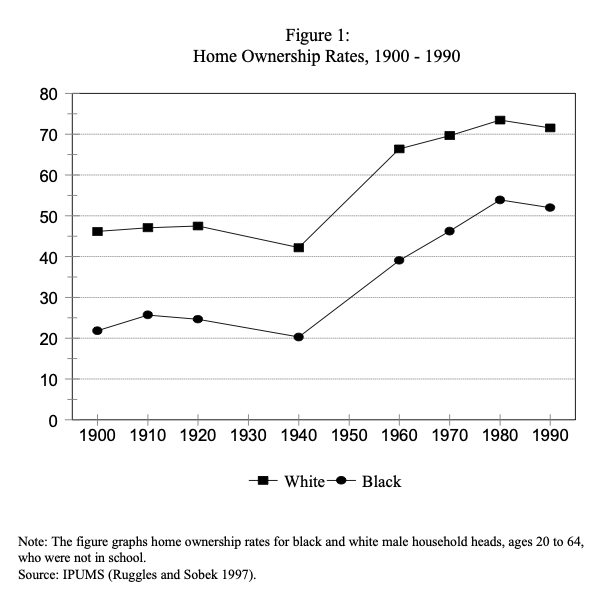

Before World War II, the United States was a majority renter society; however, that changed in the 1950s when generous G.I. Bill provisions made it possible for millions of Americans to become purchase homes, a shift that was transformative to the society both economically and socially. Researchers estimate that 95% of the post-war housing boom resulted from generous G.I. Bill assistance.

But the G.I. Bill policies were much more generous to White Americans than they were to Black Americans. Language written into the G.I. Bill excluded roughly 1.2 million black veterans from accessing benefits, and the black veterans who were able to access these benefits were confronted with racist exclusionary mortgage lending policies, economic redlining of black neighborhoods, and restrictive racial covenants.

To get a small snapshot of the damage consider this fact–of the first 67,000 mortgages secured by the G.I. Bill for returning veterans in New York and northern New Jersey alone, fewer than 100 mortgages were taken out by people of color.

Despite these practices, many Black Americans did manage to become homeowners. However, because of widespread social and economic racism, the neighborhoods black Americans were segregated into did not increase in value at the same rate as white neighborhoods. From being ripped apart by destructive urban renewal projects, like the construction of freeways, to becoming the site of environment hazards, like toxic waste dumps, Black neighborhoods have often been where white America hides its dirty laundry, giving birth to the term environmental racism.

The American real-estate industry believed segregation to be a moral principle. As late as 1950, the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ code of ethics warned that “a Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood … any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values.” A 1943 brochure specified that such potential undesirables might include madams, bootleggers, gangsters—and “a colored man of means who was giving his children a college education and thought they were entitled to live among whites.”

TaNahisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations”

Additionally, social racism made the simple fact of being black result in depreciation of home values, a trend that continues to the present day. Research from the Brookings Institution on the devaluation of Black neighborhoods estimates that “homes of similar quality in neighborhoods with similar amenities are worth 23% less ($48,000 per home on average, amounting to $156 billion in cumulative losses) in majority Black neighborhoods, compared to those with very few or no Black residents.” Not only are these neighborhoods undervalued, they are highly segregated and provide less upward mobility for the children who reside in them.

While Black Americans tend to purchase homes with lower values, they also tend to have slightly larger mortgages than their White counterparts because of smaller down payments. However, in order to benefit from the MID, it must make sense for borrowers to pay enough interest on their mortgages to qualify for itemized deductions on their taxes. With less than 17% of middle- and lower-income taxpayers claiming the MID, the amount of money it pays into supporting Black homeownership is negligible.

Eliminating the MID would be a powerful symbolic gesture–and it would raise billions of dollars of new federal revenue annually.

The difficulties endured by Black Americans in relation to housing is too extensive to be adequately covered in this article. Two suggested resources for becoming better educated on this topic include Ta-Nahisi Coates’ essay, “The Case for Reparations,” which lays out in painstaking detail the role racist housing policy has played in destroying Black wealth in America, and Season One of The City, a podcast which relates a tale of environmental racism and government and corporate corruption in the North Lawndale neighborhood of Chicago, one of the same Black neighborhoods highlighted in Coates’ essay.

While Black Millennials may not have had to deal with some of problems of racism faced by their grandparents, the historical exclusion of black Americans from the housing market has made it less likely for them to be homeowners. According to data from the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), about 26% of homebuyers in its programs receive down payment assistance from family or friends, a number that has been steadily on the rise since the Great Recession. But for many Black families, generations of racist policies have eroded family wealth, making it impossible for elders to give a financial leg up to younger generations.

Right now as millions of people across the the United States and beyond have risen up to decry racism against Black Americans, it is important to identify what concrete steps we can take as a society to invest in Black Americans and eliminate the racial wealth gap. Eliminating the Mortgage Interest Deduction would end an extremely regressive policy, restoring billions of dollars to the federal budget annually, money that could be invested in social programs and services. It would also represent a symbolic reversal of American housing policy, shifting the policy from one that subsidizes wealth to one that actually improves the lives of low- and middle-income earning Americans.

Of course, how we would choose to invest those billions of dollars is of great significance. At this point most discussion has centered on repurposing the funds from the MID to create a $10,000 tax credit for first-time homebuyers. While the plan is well-intentioned, it would do relatively little to increase housing affordability on a grand scale, and it would nothing address systemic racism in the housing market or provide support to the lowest income and most vulnerable people.

So step one should be to eliminate the MID and commit our federal government to crafting a national housing policy centered on access and affordability. But before moving further, let’s challenge our elected officials to actually listen to needs and concerns of people of color, specifically black people. Only after taking time to learn, can we expect our government to create policies that are truly address the needs of people who have been systematically excluded for generations.

Do you have a minute to take action against the MID? Contact your local Congressional Representative and Washington State Senators. Find your Congressional Representative here. Contact Senators Maria Cantwell and Patty Murray online.

Featured photo: According to tax records the land this single-family house sits on in the historically black and redlined Central District of Seattle was valued at $160,000 as recently as 2013. The property sold for $1.2 million dollars in May of 2020. Across the United States Black neighborhoods have lower property values relative to White neighborhoods making them vulnerable to gentrification. (Photo by author)

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.