On July 26th of last year, a three-year-old boy was killed while sitting in a parked car that was struck by a box truck in Madison Valley. On Halloween night, a person was hit and killed by a person driving while crossing Rainier Avenue in the Columbia City Neighborhood. On November 4th, a 58-year-old woman died after being hit by a driver while trying to cross Aurora Avenue in the Bitter Lake Neighborhood. These are three of the 24 people killed by traffic violence on our streets last year, 14 of whom were walking, biking, or in at least one case rolling. These are the real lives behind the statistics–people who had friends and family and are now sorely missed.

Twenty-four traffic deaths is down from from 26 deaths in 2019, but up from 21 deaths in 2015, the year the City of Seattle officially committed to Vision Zero, a commitment to eliminate traffic-related deaths in our city by the year 2030. Normally traffic deaths track with traffic volumes, but that trend was broken in 2020 as traffic volumes dipped significantly due to the pandemic and work-from-home measures, but deaths stayed on the trend line. This is a nationwide trend attributed to an increase in speeding as traffic congestion decreased.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) published blog post from last week recapping the work they have done in 2020 to get us closer to zero traffic deaths, and the sad numbers that testify how far we have to go. And while the numbers of deaths might not show it yet, the city did make some important changes in 2020.

Slower is safer

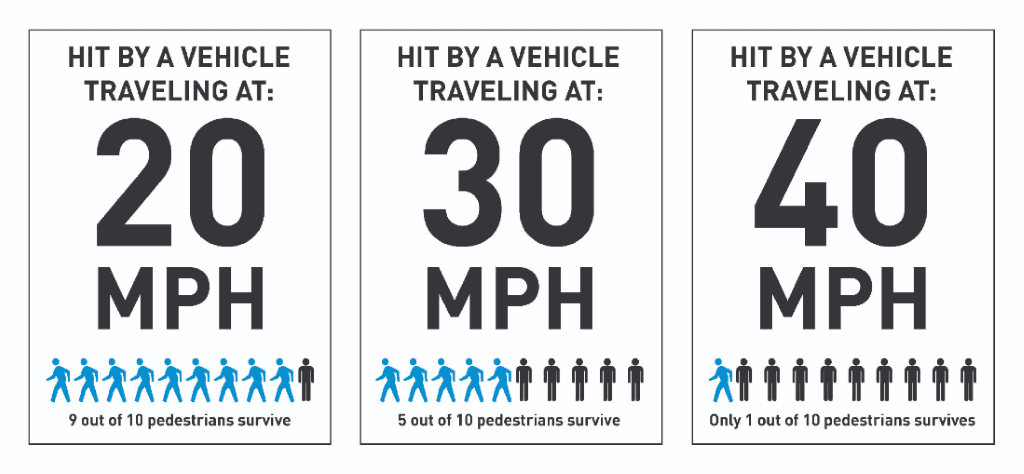

One of the biggest changes that the city made was lowering speed limits throughout the city, including 325 miles of arterial streets such as Rainier Avenue S, to 25 miles per hour. SDOT said there has been a drop in collisions on streets where the speed limit has been lowered, and even if everyone is not obeying the new limit, the average speed has dropped. And particularly with crashes that involve pedestrians or a bike rider, vehicle speed is key. While a person is likely to survive being hit by a car at 20 mph, they only have a one-in-ten chance of survival at 40 mph, which is closer to the typical speed on many of our city’s arterials. SDOT has some research to show that this change in policy is working and there has been a 20% to 40% drop in the volume of crashes where the speed limit has been lowered. But as the fatality numbers show, clearly not enough.

I live a block off of Rainier Avenue S, traditionally one of Seattle’s most dangerous streets and an arterial where the speed limit has been lowered and where a stretch of road has been reduced from four general purpose lanes to two and a turn lane. Anecdotally, the street now feels safer and drivers appear to be going, if not 25 mph, then at least slower than before. I even bike that stretch now, which I never would have before. But try driving 25 mph and watch the impatient drivers pile up behind you. Soon enough someone will pass in the turn lane or bus lane at a speed that should not be seen in city limits. Clearly more needs to be done to redesign streets beyond a mere signage swap if we want to make our streets safe for all users.

Give them a chance

We have all had the experience of the light turning and before you can step off the sidewalk a car comes flying through, trying to sneak in a turn before you can get in the crosswalk and almost hitting you in the process. Leading pedestrian intervals, having the walk sign turn green before the traffic control light, helps to minimize this situation by letting people crossing get into the crosswalk before cars can move. It has been SDOT’s other big change this year. This is a tactic that has been used in other cities and has been shown to reduce the risk of people crossing being hit by cars. In mid-2019, SDOT began reprograming traffic signals to let sidewalk users go before cars. At the end 2019, the mayor announced a goal of having 250 reprogrammed intersections by the end of 2020. And now the city has 316 pedestrian-first intersections, which is 30% of the city’s total signalized intersections. Hopefully they are not stopping at 30%. Every one deserves to know that when they step off the sidewalk, they will make is across the street safely.

More NE 65th St’s, fewer 35th Ave NE’s

While the slower speed limits and leading pedestrian intervals are big improvements, more still needs to be done reshape our roads is we want to truly make our city safe for human life. People tend to drive at the speed that feels comfortable for the road, so a wide arterial like Martin Luther King Jr Way S (where an upside down 25 mph sign which now looks to read 52 mph is closer to the reality) will continue to see dangerous speeds until changes are made to the road itself. We only have to looks at NE 65th Street, a Vision Zero project in Seattle’s Roosevelt neighborhood that reduced the general purpose lanes on a 1.5-mile stretch of arterial road and add a bike land and improved pedestrian infratrusture. According to an SDOT study, the redesigned street saw fewer collisions and injuries, slower driving, more people walking and biking, and minimal additional travel time.

35th Avenue NE was slated for similar treatment, but some neighbors fought the changes and the mayor ended up siding with them, eliminating many of the safety features. The street, while somewhat better, is still a danger to everyone not encased in steal. A before and after study showed that traffic speeds were not changed much due to the redesign and a person was killed in a crash the day after the reconfigured street opened. Unfortunately it is doubtful they will be the last.

The suburbanization of traffic fatalities

While this traffic safety analysis has been focused on Seattle, the city and traffic does not stop at municipal borders. Taking a quick look at traffic deaths between 2015 and 2019, the most recent years I could find data for and by using four years, it hopefully washes out some of the year to year noise, King County had 510 car-involved deaths or about 0.23 per 1,000 residents. Seattle had 125 deaths or 0.17 per 1,000 residents. This means that while Seattle has a third of the county’s people, it had only a quarter of the traffic fatalities, suggesting you are actually safer in city limits.

And while most of the other cities I looked at are in the neighborhood of Seattle or King County, with Bellevue and Redmond a bit lower than Seattle and Bothell a little higher than King County as a whole, Kent was an outlier at 0.39 deaths per 1,000 residents with Federal Way a bit behind at 0.29 per 1,000 residents. Tukwila on the other hand is an extreme outlier at 1.1 deaths per 1,000 residents.

This may seen like an odd segue in a recap of Seattle’s year in Visions Zero, except that due to rising housing prices in Seattle, many low-income people have been forced to relocate to Kent, Federal Way, and other more affordable suburban locations. As Angie Schmitt highlights in her great book, Right of Way, low-income people are less likely to own cars, more likely to use transit, and more likely to die from traffic violence. One side effect of displacement is forcing people to move from transit-rich inner city neighborhoods with sidewalks to transit-poor suburban locations where the street infrastructure was designed around speed and is inherently more dangerous to people walking or rolling. The result is more people are killed in the street. So while Seattle gradually makes its streets safer for its residents, it is also exporting its most vulnerable people to dangerous suburban locations.

What Does 2021 Have in Store

With the turn of the new year, the clock has reset again. On 1am on New Years’ Day, a man was hit while walking across the Montlake Bridge in what must have been our city’s first traffic fatality of the new year. The driver responsible kept driving only to be found several blocks north. Whether 2021 sets us back on our path to Visions Zero or instead sees new heights of tragedy on our streets is still unknown.

We also have a role as a community. We must hold our elected leaders and officials accountable to their Vision Zero commitment. We must decide if Vision Zero is just another empty pledge at a press conference—how many years have we been in a state of emergency around homelessness?—or whether we are done with seeing our friends and neighbors killed while trying cross the street or get to work. Are we willing to trade a little speed and convenience for safer streets and less heartbreak? I hope so. I hope 2020 was a high point we shall never see again.

Patrick grew up across the Puget Sound from Seattle and used to skip school to come hang out in the city. He is an designer at a small architecture firm with a strong focus on urban infill housing. He is passionate about design, housing affordability, biking, and what makes cities so magical. He works to advocate for abundant and diverse housing options and for a city that is a joy for people on bikes and foot. He and his family live in the Othello neighborhood.