As a first step to authorizing a new transit funding agreement with King County Metro, the Seattle City Council approved an updated agreement on Monday to guide the process for purchasing and providing service in the city. The agreement sets out the responsibilities and binding terms that both agencies are expected follow in making bus service changes and funding decisions through the end of 2027. Most of the terms are similar to the original agreement, but circumstances of over the past few years have led to the City and Metro to seek more certainty on specific matters like revenue sharing and ramping down service.

Changes to the agreement terms were precipitated by renewal of the Seattle Transportation Benefit District (STBD) in November via Proposition 1. Voters overwhelmingly approved Prop 1’s new six-year 0.15% sales tax for transit investments. This replaced the $60 car tab fees and 0.1% sales tax that had been in force for six years but were set to expire in December. A new car tab fee extension was not included in the ballot measure due to uncertainty from a pending statewide court case. That case was only resolved in October when the Washington Supreme Court struck down I-976, allowing local transportation car tab fees to continue being collected.

Agreement terms and cost considerations

Under the terms of the original agreement, there are several critical principles that are outlined and will be carried forward into the new agreement. These include things like:

- Metro not supplanting local service required by the service guidelines with City funding (i.e., funding is for additive service over baseline service);

- Ensuring that Metro provides credits to the City for farebox revenue collected in relation to additive service on City-funded routes; and

- Requiring that transit service is consistent with both the City’s transit master plan and County’s service guidelines.

Traditionally, Seattle purchases bus service at a rate that matches Metro’s basic full hourly service cost unlike other contractors that may pay a mark-up price. This basic cost, referred to a “fully allocated cost”, includes things like wages and benefits, fuel, maintenance, and some administrative costs (e.g., planning and human resources). However, Seattle does get a modest cost reduction on this for farebox credits and equipment purchases (i.e., extra buses the city purchased for trolleybus routes) under the agreement. This has usually meant that the hourly service cost is about 25% less than it otherwise would be. Costs are invoiced on a quarterly basis and paid by the City, but an end-of-year reconciliation process is conducted to deal with any differences from estimated costs and assumed service hours delivered versus actuals.

The pandemic hit Metro hard in 2020, forcing the agency to temporarily suspend fare collection throughout the spring and summer, only bringing it back in October. That led to months of an entire revenue stream drying up for both agencies. When farebox collection has been in effect, farebox recovery has been relatively very low due to capacity restrictions on buses and lowered systemwide ridership. As a result, one change that Seattle is seeking in the new agreement is to share in federal pandemic relief funding proportional to City transit service purchases.

Metro has been a major beneficiary of federal pandemic relief funding. In April, the agency received a substantial sum of money under the initial Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to keep operations going. Additional funding was authorized in December and more is promised to come under the next federal economic relief bill, which is thought to put transit agencies nationally in a safe financial spot through September 2022.

Other key changes in the new agreement include:

- A new financial periodic review of Metro’s key cost drivers that figure into the cost of transit service;

- Provisions allowing other mobility tools like DART, Via to Transit, and Ride2 to be purchased under the agreement;

- An automatic trigger that forces both agencies to collaborate on mitigation strategies when service costs or fare revenues affect service levels;

- A new provision that allows for mutual agreement by the agencies to suspend parts of the agreement that are an obstacle to preventing or reducing service reductions;

- A new disclosure requirement for Metro to notify the City when a new policy or practice has been adopted that could affect service levels; and

- A new ramp-down provision so that no service changes results in more than 100,000 annual service hours being reduced.

The latter change is designed to blunt the impacts of a possible future loss of funding from the City for transit service, giving Metro time to deal with staffing and resource changes. This means that instead of one large service reduction close to the end of the transit service funding agreement, a ramp-down of service would be phased in over two or more service changes.

Seattle’s new transit service agreement is expect to represent about 3% to 4% of Metro’s total annual service hours. Previously, that had reached as much as 8% of Metro’s annual service hours in the heyday of ridership demand. But demand has fallen for peak-hour service and the new STBD measure is much smaller in scale, reducing the volume of service hours that the City can afford to buy.

In the years ahead, cost control will be ever more important with a more limited amount of City transit funding. For Metro’s part, that has been a real challenge where yearly service costs have risen by about 5% per year–well ahead of local inflation rates. So within that context, it is understandable that many of the new agreement terms are focused on containing and minimizing cost increases.

Before the new agreement terms can go into effect, the Metropolitan King County Council needs to co-sign with approval. Companion legislation is pending before the body, but it is widely expected to be approved in the coming weeks.

Looking ahead

In March, the Seattle City Council will determine how to spend excess funding from the $60 car tab fee. There is still approximately $23.7 million of unspent money from the fee that was held in reserve pending the decision on I-976. Mayor Jenny Durkan has already developed a plan that would spend $12.7 million on projects paused last spring due to Covid and $5 million on essential transit service. The remaining $6 million would be put into a reserve account for transit service down the road. Later in the month, Metro will implement the spring service change on March 20th, adding back some bus service in the city. The City’s new transit funding service is expected to go into effect then.

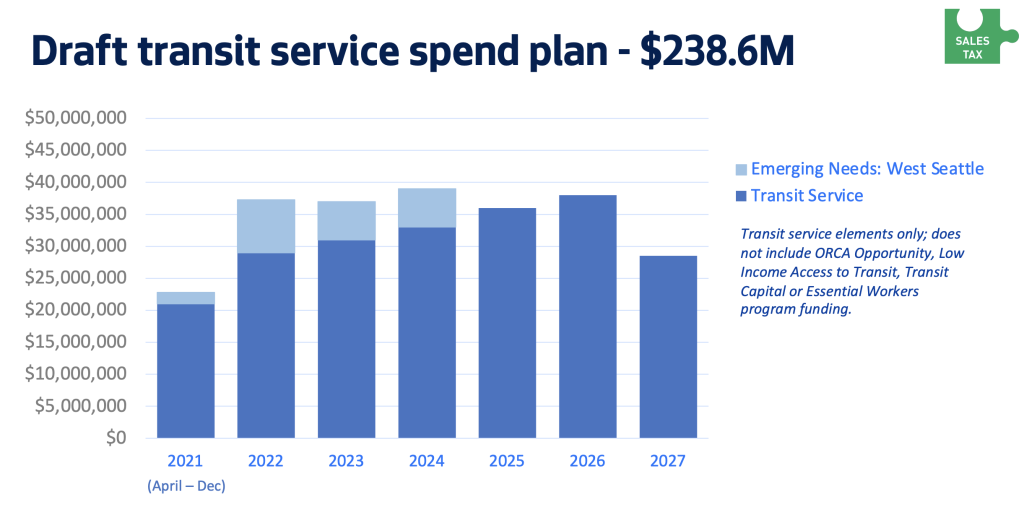

The spending plan still in development for the STBD assumes that $238.6 million will be spent on transit service through 2027 plus emerging transportation needs in West Seattle through 2024. The plan generally increases transit service spending each year of the plan, except in 2027 when a service ramp-down is assumed. Emerging needs for West Seattle are focused on the first four years as solutions for the West Seattle Bridge repair are worked out. This year will have the smallest expenditures in large part because the plan timeframe is April to December.

Then in April, further legislation is expected to consider a new $20 car tab fee that would be councilmanically imposed. A formal spending plan is still being developed, so details are forthcoming.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.