The Seattle City Council has approved additional hiring bonuses for police officers aimed at boosting the Seattle Police Department’s (SPD’s) number of trained and deployable officers. The legislation, which passed 6-3, allows for SPD to spend an additional $289,000 on hiring bonuses in 2022 on top of the $1.5 million approved in May. Per the legislation, experienced officers joining the force as new recruits will be eligible for hiring bonuses of up to $30,000 as long as they remain with the department for five years. The Council also passed amendments sunsetting the hiring bonuses at the end of 2022 and subjecting them to an evaluation of their effectiveness.

Legislation sponsor Lisa Herbold (Councilmember District 1) pointed out prior to the vote that the hiring bonuses would not require an increase in spending on the police force by the city government. “The bill uses existing funds already in SPD’s budget in support of the hiring plan that the Council already voted for and was already funded in the 2022 budget,” Herbold said.

While emphasizing the need for Seattle to adopt the hiring bonuses in order to remain competitive with other police departments locally and nationally, Herbold also acknowledged that the data around the effectiveness of the bonuses has been mixed so far. A 2019 study undertaken by the City analyzing the impact of police hiring bonuses found that while about 20% of applicants cited bonuses as one reason why they sought to work at SPD, the bonuses could potentially have a demoralizing impact among officers already active on the force if their “financial package does not match what external recruits receive.” This finding was referenced by Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda (At-Large) in connection to her dissenting vote on the legislation.

“Hiring incentives can break trust with existing personnel,” Mosqueda said.

For Herbold and other supporters on the Council, however, the bump in the number of applicants made the bonuses worthwhile. “By the public safety civil service’s best estimate, for every 1,440 applicants, Seattle may be able to hire 30 police officers,” Herbold said describing the difficulty SPD has experienced in its recruitment and hiring processes.

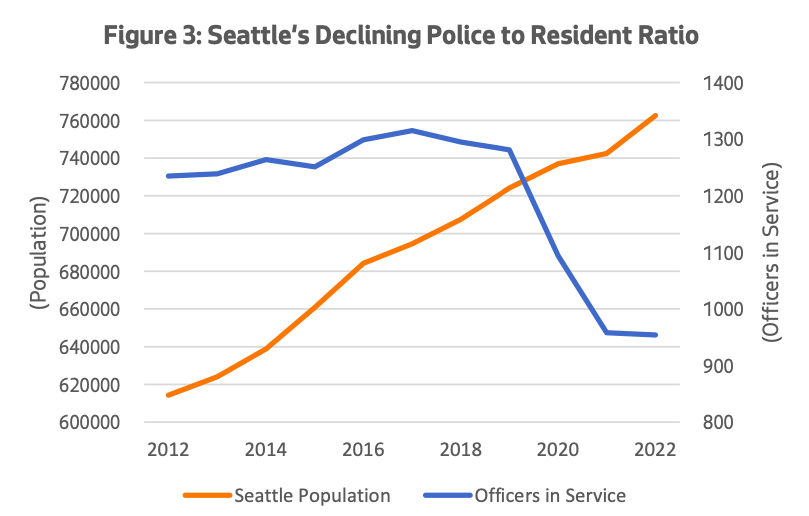

The hiring bonuses are a component of a police hiring and incentive plan proposed by Mayor Bruce Harrell intended to increase SPD’s number of trained and deployable officers from 945 to 1,450 in the next five years. This increase in police officers would surpass the number in SPD’s ranks in 2013-2019 during which the department was staffed by about 1,300 officers. Mayor Harrell has called the increase necessary in order to keep up with the city’s population growth and an increase in crime following the Covid pandemic in keeping with national trends.

For those councilmembers voting against the legislation, however, the hiring bonuses were a misguided attempt at increasing public safety. In addition to citing impacts on existing officers, Councilmember Mosqueda said she felt it was inappropriate to approve the hiring bonuses while the City was still in the midst of negotiating a new contract with SPD. She also mentioned how while the City has approved funding police alternatives, it has failed to progress forward with implementing them.

“There is no amount of funding that compensates for not being able to refer folks who are in the midst of crisis,” Mosqueda said, referencing how police officers had expressed dissatisfaction at the lack of a “landing zone for folks in crisis” to human service providers.

Fellow dissenters Councilmembers Tammy Morales (District 2) and Kshama Sawant (District 3) also made reference to lack of movement in advancing police alternatives and increasing investment in human services and affordable housing as influencing their votes.

“We know that we have a lot of challenges in the city and they won’t be solved by the police,” Morales said.

While also expressing frustration with the City’s failure to advance a police alternative pilot, Councilmember Andrew Lewis (District 7), attributed his supporting vote to the challenging conditions around police hiring across the country.

“We know that we are nationally in a very competitive marketplace for attracting and recruiting members of the police service,” Lewis said.

At least one other major police department in the Northwest has moved forward with piloting police alternatives while also embracing hiring bonuses. In June, the Portland City Council approved $500,000 in funding for hiring bonuses. Experienced sworn officers can receive up to $25,000 in hiring bonuses, while public safety support specialists can receive bonuses of $3,000-$5,000. Public safety support specialists are unarmed public safety workers who have been responding to incidents like cold theft calls, vandalism, and non-injury incidents in Portland since 2019.

In Seattle, the most significant law enforcement changes that have occurred since protests against police in the summer of 2019 have included moving 911 dispatch staff from SPD to the civilian Community Safety and Communications Center and reassigning parking enforcement officers to the Department of Transportation.

Police hiring bonuses are widespread around the region and nation

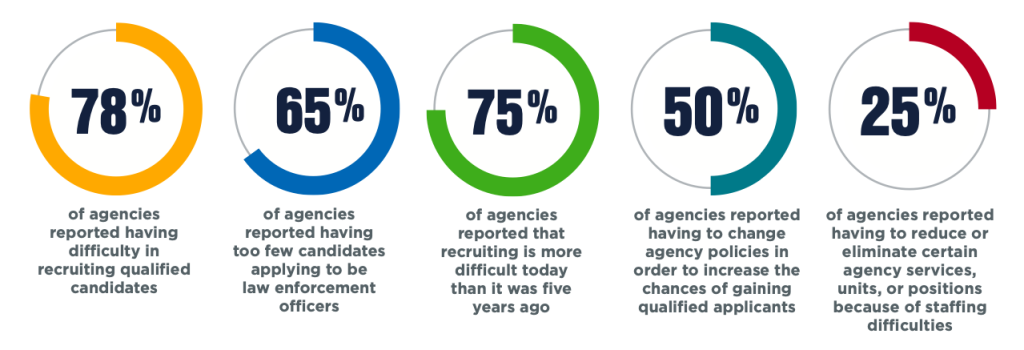

Seattle is far from the only city to struggle with recruiting and retaining police officers. While this trend has become particularly pronounced since 2019, many agencies expressed difficulty in recruiting and retaining officers even prior to that. A 2019 study by the International Association of Chiefs of Police found that across the United States over three quarters of police departments had reported difficulty in recruiting new officers.

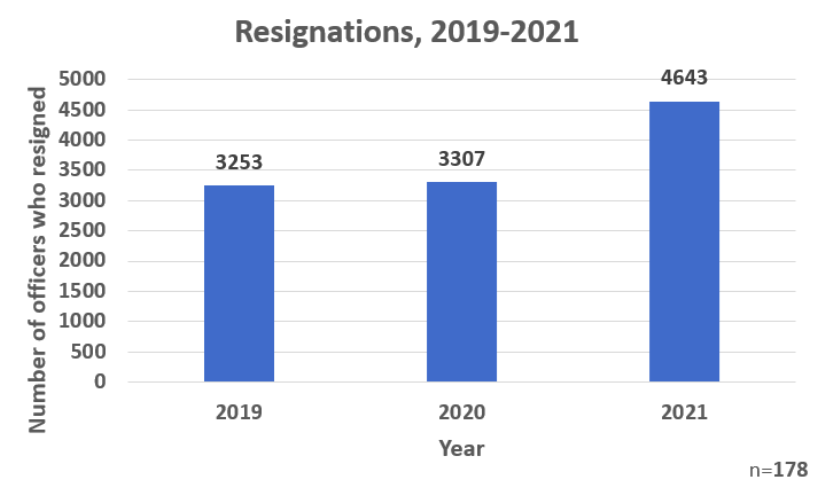

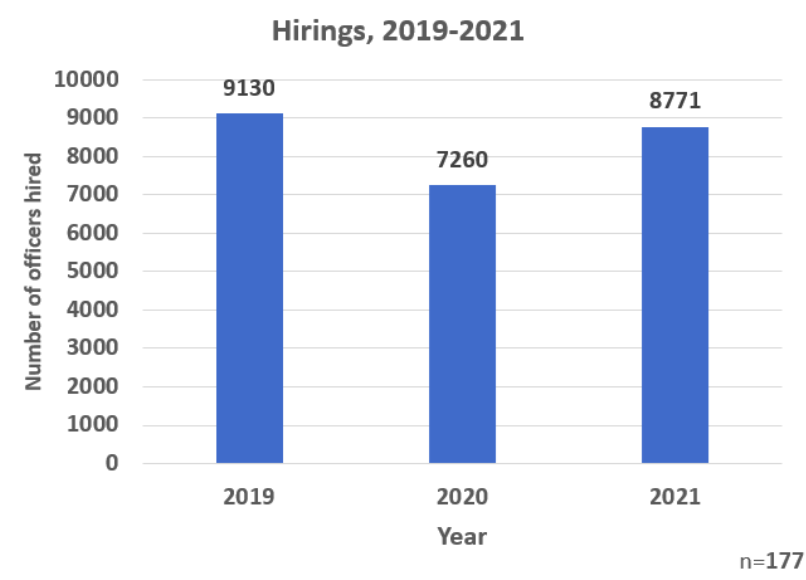

Data indicates that the hiring landscape has become more challenging since then, although police officer hiring numbers appear to have been on the increase in the last year, which could be linked to more widespread adoption of hiring bonuses and other incentives. Still, a 2022 Police Executive Research Forum survey found that among the 179 responding police departments retirements and resignations continued to rise disproportionately to new hires.

In the face of this pressure, cities have been adopting increasingly competitive police bonuses, and Washington State has been a standout in this regard. While Seattle’s hiring bonus of up to $30,000 for experienced new recruits is significant, it is not out of step with hiring bonuses offered by other cities in the region. In addition to a hiring bonus of $25,000, the City of Kent offers 400 hours of frontloaded paid leave (200 hours person, 200 hours sick leave) to experienced officers. Everett also offers experienced in-state officers up to $30,000 in hiring bonuses and $25,000 to experienced officers coming from out-of-state. Departments offer much more generous incentives to experienced, or what they call lateral hires, rather than to recruit new officers who will need to complete academy training or have only recently graduated from the police academy.

In general, it has become commonplace for cities in the Puget Sound region to offer hiring bonuses of $15,000-$25,000 in hiring bonuses for experienced officers, with Bellevue, Tacoma, Federal Way, Auburn, Tukwila, and Kirkland all offering incentives in this range. Elsewhere in the state, cities have been less aggressive. A review of Bellingham’s police hiring page reveals no information about hiring bonuses, and Spokane offers the lower sum of $5,000 as a bonus for new recruits.

The Spokane County Sheriff Office, however, did make some waves in 2021 when it paid for billboards recruiting new officers to be installed in the Seattle area, Denver, Portland, Austin, and even for two days Time’s Square in NYC, after approving a $25,000 hiring bonus for experienced and $10,000 for new officers.

Salaries have increased as well; a review of salaries shows that an experienced police officer joining a Puget Sound department can expect to start out earning about $100,000 annually. And that’s before taking overtime pay and other incentives into account. The Seattle Times analyzed SPD compensation in 2019 and found median gross pay of $153,000 for sworn officers, with some pulling in much more than that, buoyed in part by back pay negotiated in their 2018 contract.

The prevalence of these hiring bonuses and incentives raises big questions in regards to equity, with more affluent jurisdictions attracting more experienced and qualified officers, while those with less resources express frustration with serving as police officer “training grounds” for municipalities that can outcompete them. This trend is found nationally, with virtually all well-funded police departments offering hiring bonuses, incentives, and higher salaries to new recruits.

Questions about policing staffing and incentives remain

While investing in hiring bonuses and incentives to increase new police recruits has become widely adopted, the vexing question of how many sworn police officers are actually needed in a department persists. Research funded by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) shows that while many police departments cite being understaffed, few are able to demonstrate what level of officer staffing they need to meet the demands of their community.

Most cities estimate what police officer staff load they need on a per capita basis, as has been done by the Harrell administration in Seattle, or by using staffing approaches that set baselines historic staffing numbers. However, the DOJ’s research advises instead that police departments use a performance-based approach to police staffing that looks closer at officer workload and responsibilities.

While many agencies have fewer sworn staff numbers

than budgeted, the notion of a “full staff”—let alone what may constitute evidence of understaffing—appears to be subjective. Typically, police personnel consider their agency understaffed if their current number of officers is below their allocated level.This is problematic if the allocated

A Performed-Based Approach to Police Staffing and Allocation, Jeremy M. Wilson and Alexander Weiss, Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S Department of Justice

level is not based on any kind of workload or performance assessment. In this situation, officers might feel there

is a lack of commitment to the police and that they are overworked, even if the agency has enough officers to meet current demand.

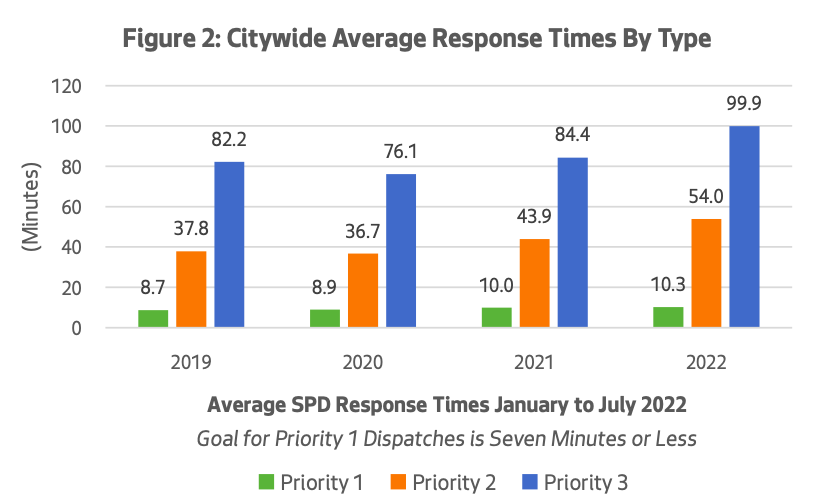

Seattle appears to be an interesting case in this regard. While SPD has reported concerning trends, such as not pursuing sexual assault cases due to staff reductions, police response times to Priority 1 incidents, which involve lethal threats, have only increased slightly since 2019 and remain relatively close to the City’s stated goal of seven minutes or less. Conducting a performance-based review of SPD’s work might reveal ways workload and tasks could be approached differently to result time-savings for response times to all levels of incidents.

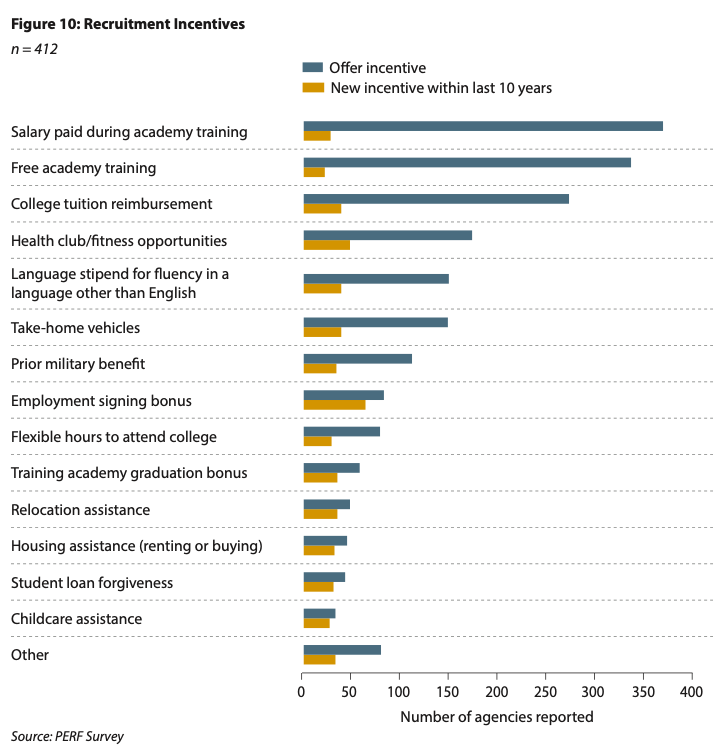

Additionally, while financial hiring bonuses have been appealing to departments in recent years, it may be worth examining other incentive possibilities that may increase both recruitment and retention more sustainably. One example of an underutilized incentive in police recruitment is access to childcare, which is commonly mentioned as a concern by police officers in surveys and also could serve to grow the number of female police officers, which continues to lag behind male officers nationwide.

Making police academy training free to eligible recruits and offering a salary during time spent in the academy are also incentives linked to hiring more officers from low-income backgrounds and underrepresented communities, while offering student loan forgiveness has been connected to attracting recruits with higher levels of education.

As the landscape for recruiting and retaining police officers remains competitive locally and nationally, it seems unlikely that reliance on hiring bonuses and incentives will disappear anytime soon. However, it will also be interesting to see what can be learned from the report assessing the impacts of these bonuses on SPD that will be completed after the bonuses sunset in 2022. Looking to the future, it does not appear sustainable or equitable for cities to use hiring bonuses and incentives to compete for experienced police officers as a longterm recruitment strategy. More data driven analysis of police staffing needs and wider adoption of civilian workers, like public safety support specialists, may help ease some of the pressure from police departments, but these changes will need to gain greater acceptance among agencies and will take time to institute.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.