Newly unearthed records show SPD exploited a policy loophole, deploying dangerous and toxic weapons during the 2020 protests via partner agencies with little to no accountability

Four days after George Floyd was murdered, the Seattle Police Department’s (SPD) then-Assistant Chief Steve Hirjak sent out a call for help, requesting police support for protests planned on Saturday, May 30th, 2020.

Over the next week, at least 23 different police departments (PDs) or agencies would respond or assist, including personnel from Auburn PD, Bellevue PD, Bothell PD, Edmonds PD, Federal Way PD, Kent PD, King County Sheriff, Kirkland PD, Lynnwood PD, Mercer Island PD, Mill Creek PD, Monroe PD, Mukilteo PD, Mountlake Terrace PD, Pierce County Sheriff, Port of Seattle PD, Redmond PD, Shelton PD, Snohomish County Sheriff, Tukwila PD, the Washington State Department of Corrections, the Washington State National Guard, and the Washington State Patrol (WSP).

Many of these cops were automatically commissioned as Seattle Police officers during this period, granting them all the privileges and power to use force within the City of Seattle under a “Mutual Aid” agreement signed into law in 2005. However, while these cops flooded the streets, their use of force, reporting, and accountability practice, did not appear to be governed by SPD policy.

Documents obtained through public records requests show that outside agencies used obscure weapons not explicitly included within Seattle’s Title 8 Use of Force policies. In fact, Seattle’s police manual explicitly applies only to “employees” of SPD, appearing to leave a major tacit exemption for hundreds of regional police when they responded to Seattle in 2020.

These agencies filled that void with toxic and dangerous weapons known to have previously resulted in countless injuries to the public worldwide. In Seattle, injuries resulting from police violence were extensive. A study by volunteers associated with the University of Washington School of Public Health showed the extraordinary human and public health toll this violence caused. Most infamously, a WSP trooper, summoned to Seattle by SPD, was filmed making a directive to his troops: “Don’t kill them, but hit them hard.”

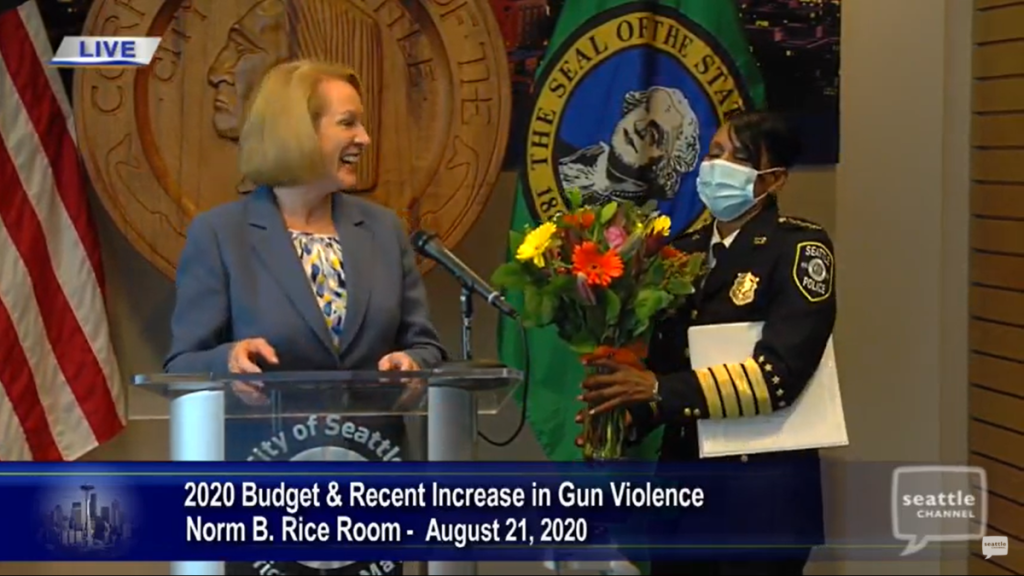

On the three-year anniversary of that protest and the brutal police crackdown that quickly ensued, no police departments have accepted responsibility for the use of banned weapons or the chaotic response that ramped up violence while failing on most metrics of crowd control. Rather than develop an effective strategy, the Seattle Police Department ended up abandoning the East Precinct and concealing who gave the order for years, with public records obtained by The Urbanist suggesting Police Chief Carmen Best and Mayor Jenny Durkan were in on the plan, even if they subsequently denied it, destroyed public records, and fired whistleblowers to obfuscate their role.

‘Mutual aid’ brings toxic banned weapons

The weapons that partner agencies brought in to respond to the 2020 protests were extensive and well beyond what SPD was authorized to use.

Bellevue PD used weapons such as “Stinger” rubber pellet blast grenades. However, under a “combined WSP and SPD order limiting the use of Stinger Rubber Blast Balls,” they were prohibited for use by WSP and SPD according to WSP Public Affairs Trooper Darren Wright. These types of grenades expel tiny rubber pellet shrapnel, affecting everyone near the explosion in a 50-foot radius according to the manufacturer. With a density of 10-square feet per person in a crowd, a single blast could strike more than 700 people.

“Stinger” rubber pellet rounds were also used by Tukwila PD and the King County Sheriff. These rounds were shot from a 40-millimeter gun, with shells over twice as big as a typical 12-gauge shotgun. These weapons are packed with between 18 (60-cal) and 130 (32-cal) rubber pellets shot at 300 feet per second.

King County Sheriff deputies also shot multiple 12-gauge shotgun “beanbag” rounds at protesters. Filled with #9 lead birdshot BB’s, they have caused countless injuries, especially when fired at the head. These were the same weapons that left Scott Olsen, shot by Oakland PD during the Occupy Protests in 2014, in a medically-induced coma, costing the city of Oakland $4.5 million in a negotiated settlement.

“Military Style SAF Smoke” was also used by Tukwila PD which contains acutely toxic and carcinogenic chemical agents. The intended effect of these smoke agents is unclear, as the manufacturer indicates they can be used to conceal “the movement of agency personnel. It may also be used as a distraction to focus attention away from other activities.”

WSP also used “HC Smoke,” canisters during crowd control tactics. According to the Portland-based Chemical Weapons Research Consortium, these canisters release lethal-to-human levels of carcinogenic toxins into the air. Each canister contains enough chemicals to kill 10 people each according to Dr. Juniper L. Simonis, a quantitative ecologist. WSP deployed at least four smoke canisters.

Additionally, 40-millimeter “warning / signaling” rounds, used by WSP during the protests, are a munition that “deflagrates” (or combusts) 50 meters away from the shooter, producing a five million candela and 170-decibel explosion. WSP training instructs them to shoot the munition to detonate it “20 feet above the head of the crowd.” Other manufacturers call these “Aerial Flash-Bang” devices, essentially flash-bang grenades fired from a grenade launcher in layman’s terms.

In one instance, Kent PD was “advised by the [SPD] officer in charge to launch” 40-millimeter CS Skat shell munitions. At another point, an SPD SWAT team member asked for and took five “launchable CS munitions” from a Kent PD officer while in the field, according to Kent PD case files. Body-worn video obtained through public records requests appears to show an SPD SWAT team member using chemical agents released from a 40-millimeter gun. It is unclear if the use of these munitions were tracked or reported as a use of force by SPD.

None of these weapons are explicitly permitted within SPD’s Title 8 Use of Force policy. Additionally, SPD policy only allows for the use of weapons issued by SPD, not taken from other agencies, raising questions about the unknown SPD SWAT officer’s potential use of Kent PD munitions and the use and tracking of 30 CS grenades handed to SPD then-Lt. John Brooks from North Sound Metro SWAT in the field. WSP also reported providing SPD with 48 “blast balls” and 60 “hand toss gas” while in the field.

The use of these weapons raises significant questions about where SPD policy starts and stops with respect to external agencies responding to Seattle. While SPD has arduously worked to vet policies and weapons use with the U.S. Department of Justice and federal monitoring team, the invitation of external agencies to Seattle appears to invite them to sidestep over a decade of policy reform and federal oversight required under the consent decree Seattle signed in 2012.

Leadership vacuum leads to chaos, widespread use of banned weapons

If SPD holds a backdoor policy that allows for the use of these weapons, that policy is not available to the public, nor are the conditions for the use of these specific weapons. If SPD solely relied on communication with these agencies to prevent the use of certain types of weapons, that dialogue appeared chaotic and indecisive.

Body-worn video obtained through public records requests show Kent PD officers on the ground asking “What’s the plan?!” as they held hundreds of people back on May 30th, 2020. An SPD bike team sergeant rides up behind the line, and is asked “what’s the plan? Are we just holding for now, or..?” He replies, “I don’t know.”

A few minutes later, another SPD bike Sergeant rides up with his entire bike squad behind. A Kent PD officer then asks him, “What’s the plan now?”

The SPD sergeant responds, “I have no idea.”

Kent PD appeared to be shuffled around. When deployed to the Westlake area, as King County Sheriff Deputies deployed huge opaque plumes of chemical agents, a Kent PD officer asked, “What the f*** are we doing?” as other officers in gas masks shook their heads.

King County Sheriff’s After Action Report showed that, “There didn’t seem to be any direction from them [SPD]. We didn’t really have a direct way to communicate with SPD unless the Sgt’s called SPD SWAT directly. TL’s [Team Leaders] were also telling guys to do one thing without seeing what the Sgt’s were being told. There was a lot of confusion with the ranks at times as one TL would say to do one thing and the Sgt’s telling us to do the opposite.”

Other agencies also came away with similar concerns. When summarizing the day’s events to other chiefs, commander of the North Sound Metro SWAT team, Glen Koen, wrote while embedded at the Seattle Police Operations Center: “honestly, at times it was difficult to tell who was in charge and to discern what the plan was.”

Koen’s personal cell phone texts revealed that their officers were heading to Seattle with “no clear assignment.” SPD was not returning their calls.

On initial coordination with the Washington State National Guard, SPD “asked what our RUF [Rules for Use of Force] was going to be, so they didn’t have a plan for it.” SPD Assistant Chief Deanna Nollette voted for them to come fully “armed.”

Snohomish County Sherriff pulls out

A week later, on June 7th, Snohomish County Sheriff (SCSO) deputies would raise the alarm while deployed to Seattle to help SPD augment patrol staffing. SCSO sergeant Cynthia Caterson wrote in an update that SCSO deputies “are now working alone in the North Precinct area (not riding with SPD officers, no SPD radios). SPD patrol officers are just lounging around the precincts and not responding to calls, so SCSO going [sic] to many calls and normally alone.”

The next day, SCSO Operations Bureau Chief Ian Huri would write to his colleagues, “I have contacted SPD and let them know we will not have any units to assist them tonight. I would like to see a better plan come together from SPD…” This was first reported by Carolyn Bick of the South Seattle Emerald.

Mutual aid overreliance leads to SPD’s Proud Boys ruse

SPD then devised a false reporting ruse, broadcasting false radio transmissions over the radio about Proud Boys preparing for violence against protesters. SPD Captain Bryan Grenon said said one of the reasons this hoax was initiated was “because of the political situation, all our mutual aid partners … had abandoned us.”

The use of mutual aid and the hundreds of individual uses of force they exerted on protesters during this period would become integral to SPD’s strategy of crowd control. Without them, SPD felt forced to improvise the Proud Boys “ruse,” in which officers falsified radio reports of armed right-wing extremists nearing the Capitol Hill Organized Protest.

Mutual aid police forces also made disturbing and denigrating comments while deployed to Seattle, and bragged about the amount of overtime pay they were raking in. One exclaimed, “enjoying the overtime!?” Another said, “more overtime to pay for your patio furniture!” One officer walking down 4th Avenue after the city had been inundated with chemical agents and blast grenades said, “You know what though, to me it even looks better after this, because there’s no tents and people laying on the side of the street.” Another officer stood at 6th and Pine, staring at a crowd of protesters, he said, “I’m just waiting for a car to come barreling in here man.” Another cop said, “Yea!”

A few days later, a family member of an SPD officer would drive into crowded 11th Avenue, exit his car and shoot Dan Gregory before surrendering to police.

No accountability or guarantee this won’t happen again

In all, WSP had used at least 261 Uses of Force, in addition to “~1000s” of pepper balls shot at protesters, according to internal documents between May 30th and June 4th alone. The totals are staggering: Bellevue PD tallied at least 69 official Uses of Force, Kent PD at least 25 Uses of Force, Redmond PD at least 2 Uses of Force, Tukwila PD at least 6 Uses of Force, Port of Seattle PD at least 65 Uses of Force, and KCSO at least 119 Uses of Force on people within Seattle during the 2020 protests.

Of the likely-undercounted 547 total Uses of Force (not including the thousands of pepper balls) by mutual aid agencies responding to Seattle, it does not appear that the Seattle Office of Police Accountability (OPA) or SPD investigated a single one.

Since 2019, Seattle’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) has been completing an audit of SPD’s use of “mutual aid.” The results of this audit, ongoing over four years, have not been made public. Even prior to the 2020 protests, OIG highlighted “potential impacts associated with this topic include use of force, bias, improper consideration of immigration status, and discipline.” Any OIG work in this area failed to mitigate the harms caused by mutual aid forces in 2020. OIG has not responded to questions about the audit’s status or revealed why the audit is still ongoing after four years of work. The use of force by mutual aid was conspicuously omitted from the OIG’s Sentinel Event Review reports produced over the past two years.

The Mayor’s Office, SPD, OPA, OIG and the Federal Monitoring Team were all contacted for this article. None responded to comment.

Without a policy intervention, these mutual aid forces will continue to use violence with little accountability when called upon by Seattle Police command.

Glen Stellmacher (Guest Contributor)

Glen Stellmacher is a licensed architect. He is a graduate and former lecturer at the University of Washington. His work can be found around Seattle and in print within Advancing Wood Architecture: A Computational Approach, Trajectories, a compendium of research on robotics, digital design, fabrication and sustainable forestry practices and online.