Washington State has 40 electric school buses so far — but big plans to change that. Meanwhile most parents drive their kids to school.

That is the sentiment Vice President Kamala Harris expressed to a handful of Seattle students, educators, and leaders in October when announcing $1 billion for electric school buses.

“It’s part of a nostalgia and a memory of — of the excitement and joy of going to school to be with your favorite teacher, to be with your best friends, and to learn,” Harris said. “The school bus takes us there.”

But like most issues connected to the climate crisis that affects younger generations, the yellow school bus fleet — a system that runs on fossil fuel — is only slowly transitioning to meet the needs of students today and in the future. It’s why Harris’ announcement was more than just a presidential visit. It’s another baseline for clean energy investment for Washington cities trying to reduce a leading cause of climate pollution: the transportation sector.

This back-to-school season, a year after Harris’ announcement, logistics for getting those buses on the road are still underway. Roughly 10,000 school buses operate in Washington state, and only about 40 of them are electric. While that’s under one percent of the total fleet, these electric buses have reduced around 500 tons of carbon emissions. That’s the equivalent of a passenger car driving just over a million miles.

These results are not just important for the state to meet its zero-emission goals, but also for protecting students from pollution coming out of the bus’s tailpipes.

“In both Washington State and across the country, if you consider school buses a form of public transportation, they are the largest fleet because there are just so many of them,” said Leah Missik, senior policy manager for Climate Solutions. “Most school buses right now in Washington unfortunately run on diesel, which is not just a climate pollutant, but also a local air pollutant that is really bad for our health.”

School bus pollution compounds environmental injustice

Across the country, fewer students are walking to school, but for the Seattle Public Schools’ (SPS) body of nearly 50,000 students, pedestrian activity has increased in recent years.

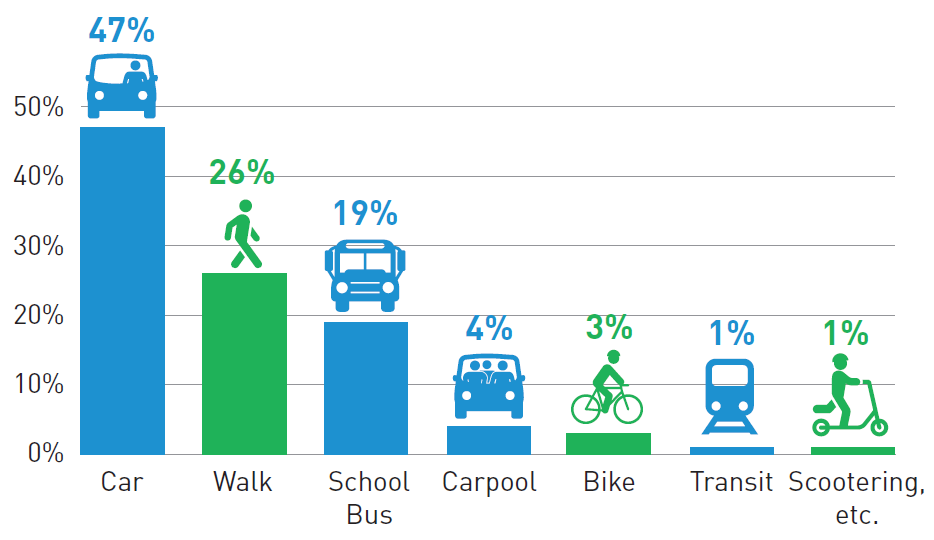

That’s in part to Safe Routes to School initiatives near campuses, a joint effort from the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) and SPS. These agencies have seen the percentages of students walking and biking to school double since they started their tally in 2005. Now 29% of elementary school students are walking and biking to school, with 47% getting a car ride and 19% taking the bus.

But it’s White students who make up most walkers and bikers when compared to students of color, who are more likely to take the bus or get a ride to school, according to a citywide survey in a five-year action plan called “Safe Routes to Schools.” In response, the five-year action plan prioritized racial equity, centering walkable street design and investing in bike gear for communities of color in Seattle.

Toward the goal of walkability, SPS has a new program called “School Streets” that started at TOPS School in Eastlake. It entails closing the street next to a school to cars to improve bike and pedestrian access before and after school. “These are requested by schools, but SDOT operates the program,” an SPS spokesperson said. “The program started during the pandemic, and it’s grown to 14 schools.”

And while Seattle has seen gains thanks to those improvements, walking or biking to school is still far less common than it was in the 1960s and 1970s.

As American cities have sprawled out and neglected road safety, the share of students walking, rolling, or biking has dropped precipitously. In 1969, nearly half of K-8 students walked to school nationwide, but by 2009 that had plummeted to 13%, according to the National Center for Safe Routes to School. Furthermore, in 1969, “89% of students in grades K through eight who lived within one mile of school usually walked or bicycled to school. In 2009, only 35% of students in grades K through eight students who lived within a mile of school usually walked or bicycled to school even once a week.”

These shifting patterns have meant increased reliance on school buses and on parents driving their kids to school, which in turn increases car traffic near schools and makes it more dangerous and unpleasant for those still walking, rolling, or biking.

State policymakers have sought to reinforce transit habits among youth with fare-free transit passes for all kids under 18 years of age, a program which was funded in the 2022 Move Ahead Washington transportation package. Some older students already take a Metro bus to and from school rather than a yellow bus chartered by SPS.

While walking and biking to school are the lowest-emission modes of commuting, it may not be an option for all students or families, whether the reason be living too far from school or unsafe road conditions on the route. In some cases, students of color are most exposed to other forms of pollution, Missik said.

“A lot of the kids who are riding these diesel buses already have factors in their lives, often based on where they live that really compound their exposure to pollutants,” Missik said. “In my opinion, it’s terrible. We have an alternative for those kids who are riding the school bus and we are not using it.”

Inhaling diesel exhaust can give people asthma and other respiratory illnesses, and children – with developing bodies and lungs – are especially vulnerable, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It is responsible for 70% of Washington’s airborne cancer risk, the Department of Ecology’s air pollution study shows.

Environmental health scientists, including researchers from the University of Washington, have found that the levels of air pollution inside school buses were up to four times higher than that on the roadway. This is likely because of how school buses idle in school yards and bus stops. The exhaust pollutes the air in the bus, and sometimes even in the classroom, throughout the day.

Diesel engines can operate for more than 30 years, and how these engines burn fuel is especially harmful. It’s why Missik and other climate coalitions in the city are advocating for funding this upcoming legislative session to get them off the street as soon as possible.

Funding for more electric school buses

In a push toward zero-emission vehicles, the Washington Department of Ecology has invested $25 million for 79 electric buses across 37 school districts. Only half of these buses are on the roads now, and the other half are expected to be delivered in the next six to nine months. That’s because funding for electrifying fleets just started in 2020 when the state received settlement money from Volkswagen – after the automobile manufacturer had allegedly cheated emissions tests, violating the Clean Air Act.

“[This funding] was really kind of the first introduction to electric school buses in the state, and so, we wanted to make sure we were partnering and prioritizing the publicly owned buses,” said Molly Spiller, Pollution Reduction Grants Section Manager for the ecology department. “However, we learned from that, that there was a lot of interest from all the school districts across the state to really make this transit transition to zero emission.”

This upcoming school year, the Department of Ecology will award another $14 million for zero emission school buses. Eligible applicants will include school bus owners that transport students to K-12 schools overseen by the Washington Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction for the 23-24 school year. That includes bus operators like First Student, a transportation company that contracts with SPS as well as Tacoma Public Schools.

First Student has committed to transitioning 30,000 diesel buses nationally to electric by 2035. Such government funding can help make that happen. They applied for and received funding from the Department of Ecology to purchase electric school buses for operation in the Tacoma district.

The Department of Ecology doesn’t oversee all grants for electric school buses in Washington state, and most federal funding will be delegated directly to school districts. Federal dollars are doled out under the Clean School Bus Grant Program, which was established by Sen. Patty Murray under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. This August $400 million was released as part of the investment the Vice President announced in Seattle last year.

“Clean school buses mean cleaner air for students and our planet and cost savings for local school districts—which is why I fought so hard to get my Clean School Bus Act included in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law,” Murray said in a statement. “As funding from my clean school bus bill goes out the door and we get a better sense of the need in our communities, I’ll continue to advocate for clean school buses—which are better for kids and our environment.”

But policymakers know that more funding is needed to accelerate the transition of this massive transit fleet. If they can acquire it, then the ride to reach zero-emission vehicles will be faster, and, to paraphrase Vice President Harris, the bus will take us there.

Ashli Blow

Ashli Blow is a Seattle-based freelance writer who talks with people — in places from urban watersheds to remote wildernesses — about the environment around them. She’s been working in journalism and strategic communications for nearly 10 years and is a graduate student at the University of Washington, studying climate policy.