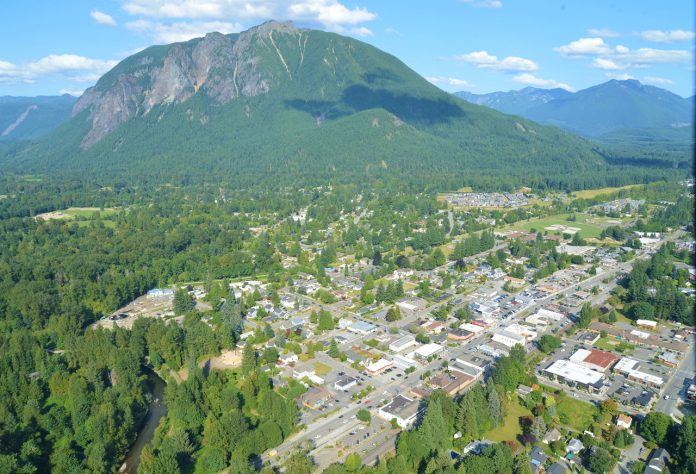

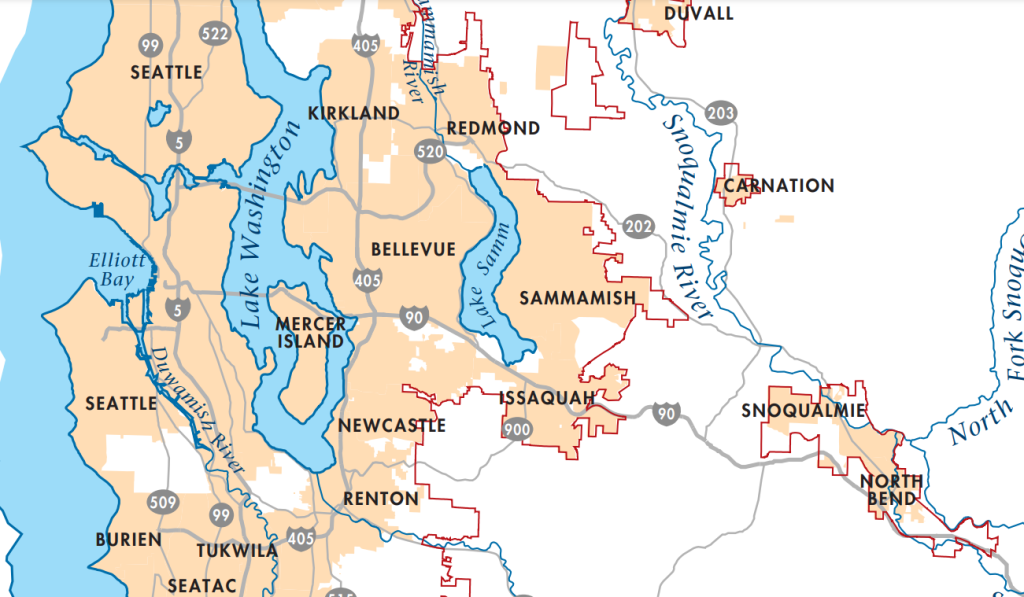

A meeting of an obscure regional planning body got tense last week as elected officials sparred over the issue of expanding King County’s urban growth boundary to encourage housing development and preservation of existing open space along the exurban fringe. The area of focus are near the cities of North Bend and Snoqualmie, an isolated patch of the county’s Urban Growth Area (UGA) along Interstate 90, with city officials there wanting to keep the door open to some types of development, and leaders representing places like Seattle and Bellevue wary of too much sprawl in the I-90 corridor.

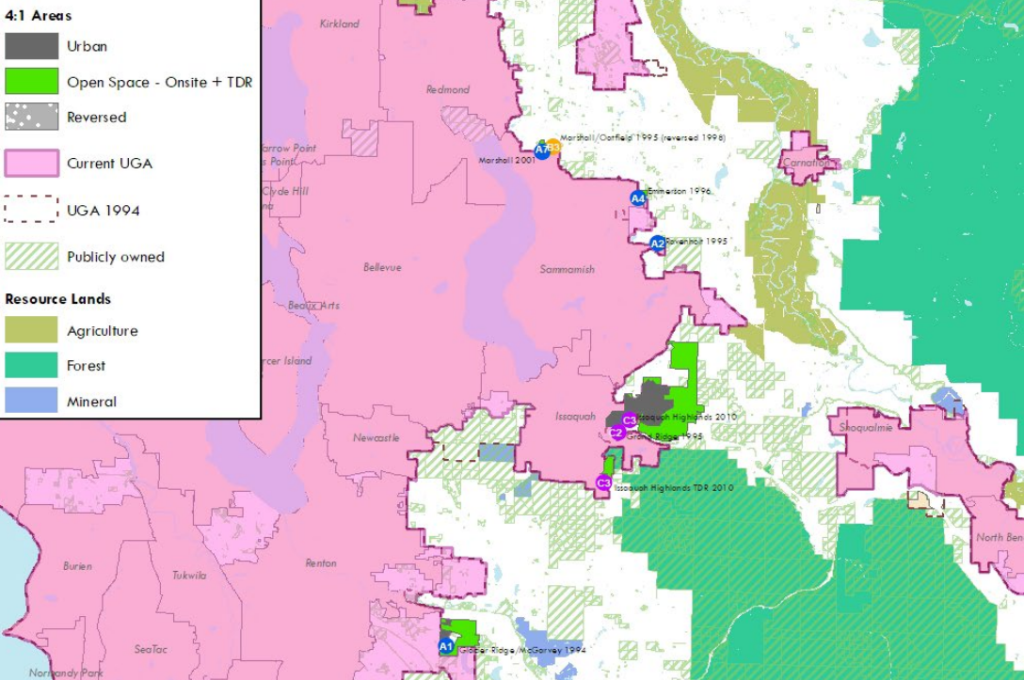

At the heart of the dispute is the wonky “four-to-one” program. An element of King County’s comprehensive plan, the four-to-one program is one of only three ways that the UGA boundary is able to be modified, changing the line established in 1994 intended to constrain urban growth. Property owners interested in developing property that’s immediately contiguous to the existing boundary, where compact development is able to be served with existing services, can apply to do so, if 80% of the property is dedicated to open space: four parts open space to every one that’s developed.

The goal of the program is to provide incentives to create a “contiguous band” of open space along the growth boundary. A 2019 review of the four-to-one program found that proposals either completed or in the pipeline added up to 360 acres of new development, coming with around 1,100 new units of housing, and the preservation of around 1,400 acres of open space. Developments include 100-acre Glacier Ridge in Renton, the first four-to-one program approved immediately after the growth boundary was set in 1994, and smaller ones like five-acre Marshall near Sammamish.

On top of that, even larger developments, like Grand Ridge in Issaquah (490 acres), have been approved using four-to-one “principles,” through what’s called a Joint Planning Agreement (JPA), that expanded the 1994 UGA boundary while at the same time adding a considerable amount of open space. It’s those existing JPA additions to the 1994 growth boundary that are at the center of the dispute now. The question is whether the county should allow new four-to-one development projects on the borders of those JPAs. The upside could be more preservation of open space, but that would come at the cost of adding more residents in harder-to-serve areas of the county at a time when it’s trying to promote the opposite.

While the county calls the four-to-one program “award-winning,” there’s not a consensus on whether approving these additions to the urban growth area has actually achieved the goal of constraining growth.

“Some of the biggest failures of growth management that we look at today, and we say, ‘that was not what we wanted, and that is impossible to serve’, those locations started life as four-to-one programs,” King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci said this spring. “This program can be problematic if we’re not careful.”

But cities like North Bend and Snoqualmie argue that the current UGA boundary, not the 1994 one, is what should be used to make planning decisions and that means allowing four-to-one development like in any other area.

“Providing a direct exchange of property into and out of the UGA appropriately allows for the right balance of urban and rural lands,” Snoqualmie Mayor Katherine Ross wrote to County Executive Dow Constantine earlier this year in a letter asking for the current boundary to be used. Ross suggested areas between the current UGA boundary and I-90 would be appropriate areas for “accessible workforce housing, medical, and/or behavioral health services.”

Changing the four-to-one program in this way across King County would add around 750 acres of developable land to the 5,500 acres that already qualify. That’s around 6,000 units of housing potentially added to the county’s urban fringes — slightly more than the official housing growth target for the city of SeaTac through 2044 and nearly five times the target of Mercer Island.

Why is this coming up now? In preparing for the major update to King County’s comprehensive plan next year, county staff discovered that a previous update in 2012 had inadvertently removed the reference to the original 1994 boundary, prompting a need to clarify. In May, County Executive Dow Constantine proposed an amendment to the countywide planning policies that would have fully closed the loophole; at the time, it failed, after a faction on the council, largely made up of elected officials in east King County but also including County Councilmember Rod Dembowski and Seattle City Councilmember Dan Strauss, supported the idea of allowing four-to-one development adjacent to the JPA areas in North Bend and Snoqualmie.

County Executive Dow Constantine pushed back on that idea. “Changing the basis of the four-to-one program would take us back in time, and allow new four-to-ones right next to the ones we already allowed, allowing sprawl even further into the rural area,” he said at that meeting.

King County Councilmember Sarah Perry, who represents the district that includes North Bend and Snoqualmie as well as much of rural King County, was at odds with Executive Constantine’s approach, and deferred to the work that local officials in those cities have been doing to plan for growth. “I really want to honor the work that the cities have done in this. And I think it’s very important to recognize that leadership, recognize the changes, recognize how they’re holding it and the work they’ve done throughout this process,” she said.

After approving the amendment that would open the door to using the boundary with those JPAs added, the county opened public comment on the proposal. Sustainable land use, transportation, and environmental advocacy organizations were fairly unanimous that the idea should not move forward.

“Both environmental and economic rationale demand that the region focus growth in our existing cities and towns where infrastructure and support services already exist. Therefore, any four-to-one program expansion should be based on the UGA line adopted in 1994 and not on later additions to the UGA in any local jurisdiction,” Sierra Club of Washington’s Tim Gould wrote the council last month.

North Bend and Snoqualmie have limited transit networks and adding service would be expensive and difficult to do effectively given their low density and distance from job centers and activity nodes. In effect, such UGA expansions mean more car trips taxing I-90 and the highway network.

“Adding UGA expansions onto UGA expansions creates an urban pattern that is more expensive to serve with public facilities and services and will generate unnecessary adverse traffic impacts and additional greenhouse gas pollution,” Hester Serebrin, policy director with Transportation Choices Coalition, wrote in a separate letter.

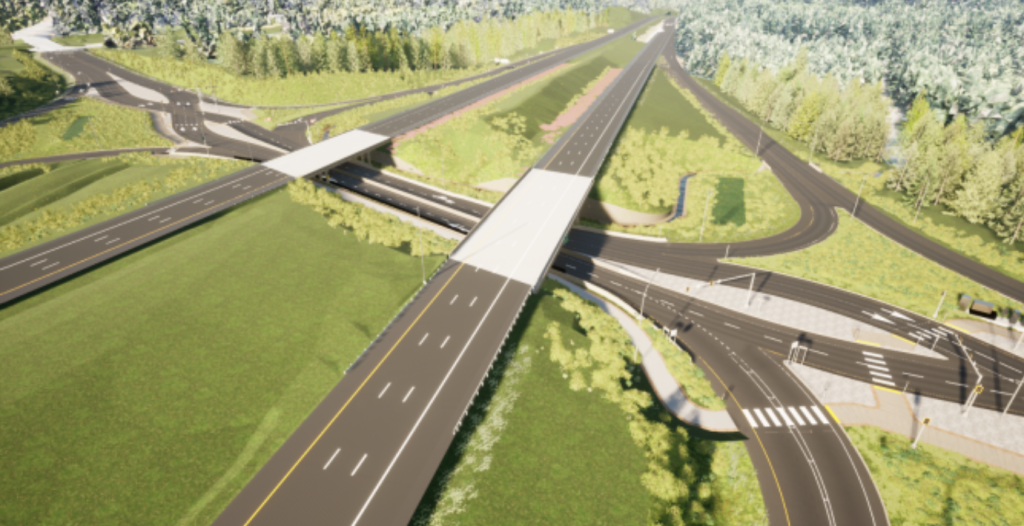

Even the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), which is in the process of expanding State Route 18, and building a new diverging diamond interchange at the highway’s outlet to Interstate 90, in large part to accommodate housing growth in the area, expressed concerns with further expansion of the urban growth boundary in this instance. Brian Nielsen, Northwest Region Administrator for WSDOT, said the policy chance could lead to “more unplanned and unanticipated challenges on the local, regional, and state transportation network” as a result of unanticipated future growth.

“[W]e maintain our concern that the recommended policies allowing exceptions for select jurisdictions are based on a request with urban development already in mind, not based on a countywide or regional need or policy rationale,” Nielsen wrote.

In the end, the planning council voted 5 to 4 to stick with the original 1994 boundary. Executive Constantine joined with County Councilmembers Claudia Balducci, Joe McDermott, Jeanne Kohl-Welles, and Seattle City Councilmember Tammy Morales to squash the expansion of the four-to-one program to additional areas in North Bend and Snoqualmie. They were outnumbered by local elected officials like North Bend Mayor Rob McFarland, but their votes carried more weight.

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell and Councilmember Dan Strauss, who both also serve on the council, were not present for the vote.

With King County finalizing housing growth targets and handing them over to cities to plan around, the vote illustrates some of the deep divisions that still exist across King County when it comes to figuring out how to accommodate growth. Given the intense opposition to changes in state law that would loosen restrictions on residential zoning, encouraging infill housing and supporting transit-oriented development, some electeds in the region clearly see reconsidering the urban growth boundary an easier path forward.

Councilmember Perry described the final vote as an urban versus rural divide, calling out what she described as a “divisiveness highlighted simply by the differences in the specific communities represented” on the planning council.

“What you’re seeing playing out is a discussion that is largely between members who represent the space outside the contiguous UGA… versus those whose jurisdictions are contained within the contiguous UGA,” Parry said.

County Councilmember Claudia Balducci painted a more existential threat that could have come from moving forward with the change that had been considered. “I tried to get to the point where I felt confident that this would not start a cascade of actions up and down the urban growth boundary, fundamentally breaking it over time,” she said in support of Executive Constantine’s amendment.

For now, the line is holding.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.