Washington State Legislature legalized “missing middle” housing across the state, allowing more homes on a lot in the form of rowhouses, duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes and sixplexes. Seattle will now need to legalize sixplex homes citywide in areas served with frequent transit and fourplexes elsewhere. This restores Seattle to a bygone era of density, affordability, and walkability that so many of us cherish in the older neighborhoods throughout the city.

These sustainable development opportunities add equitable housing in desirable neighborhoods by reducing housing costs, increasing housing supply, and housing families near schools, parks, and walkable business centers. This missing middle policy brings people closer to jobs, transit, and meets sustainability goals by lowering the city and state’s largest source of emissions: driving around for everything in personal vehicles.

But hold that thought, the planners have missed the point

The policy was written by legislators, mostly part-time members with careers in law or other businesses outside of urban planning and architecture. And because smaller jurisdictions don’t have the capacity to develop plans and ordinances to meet compliance, the Washington State Department of Commerce convened planning consultants to build a “model code” that bakes in legal language that was passed and creates a template for cities to adopt. For larger cities like Seattle and Bellevue, it may serve as a starting point. For smaller jurisdictions like Auburn or Tumwater, it will more closely resemble the finish line.

Model code will put a drag on the housing production it was supposed to encourage

The model code destroys the housing bill’s flexibility by limiting building area and micromanaging the building’s look. This bill was a remedy to solve the supply of housing, not the look of housing. Nobody feeling the anxiety of paying high rent or being evicted to the street cares what dormer requirements a planner wants to see, and they certainly would prefer a bigger building with as much housing and bedrooms built as possible. We were warned about the possibilities of a form-based code micromanaging design, building size, and circumventing the bill in clever ways, and it seems like the model code has taken those fears and made them a reality.

Right now, the Washington State Department of Commerce is taking comments for feedback until December 6. I encourage you to raise the following points:

- Raise the floor area ratio (FAR) maximum to 1.5 or consider removing FAR from the regulations entirely so we can guarantee homes are large enough for families and for a wider range of affordability.

- Remove all building aesthetic mandates and allow architectural flexibility which will provide added flexibility for low cost, energy efficient solutions to building design.

Buildings will be FAR too small

The model code is just fine on lot coverage, setbacks and building height. But planners have micromanaged a regulation to intentionally make these buildings smaller. Floor area ratio or FAR is the multiplier assigned to the site’s area that presents the maximum size a building can be. The model code caps the FAR maximum at 1.0 for anything with five or more units, meaning a typical 5,000 square foot lot will only be able to produce a 5,000 square foot building, fitting out a sixplex full of one-bedroom units or studios. At a maximum of 1.0 FAR, and subtracting the circulation and common space, the units will be 750 square feet each in a sixplex or 833 square feet as rowhomes, which are both typically too small for a family of four to even consider.

For townhomes, the 833 square feet will be split by two or three levels and include the staircase making each floor that much smaller. For sixplexes, these will either be comfortable one-bedrooms, or squeeze in a very tight two-bedroom that many families will soon outgrow. Observing the range in FAR maximums, the model code authors clearly want us to build fewer homes on site if they house families, with a duplex providing 1,500 square foot units and skewing them smaller and smaller the more homes that are added.

The model code legalizes 50% lot coverage and 35 feet in building height, enough for three stories. On a typical lot, three stories and 50% lot coverage creates a building totaling 7,500 square feet, which is 1.5 FAR, so why isn’t that the maximum? With a FAR of 1.5, the homes have a chance to be 1,200 square feet each, on a single level. These are large enough for comfortable, family-sized three- or four-bedroom apartments, and will reduce costs per square foot by spreading expensive utility construction (like kitchens and bathrooms) across more space.

If the FAR does not increase to allow larger units, then Washingtonians are likely to pay more for less housing. Banks may also be tighter with financing for smaller missing middle projects without a clear use case or market. The results won’t just be smaller homes, it will result in far fewer homes being built at all — which was the reason for the state reform in the first place.

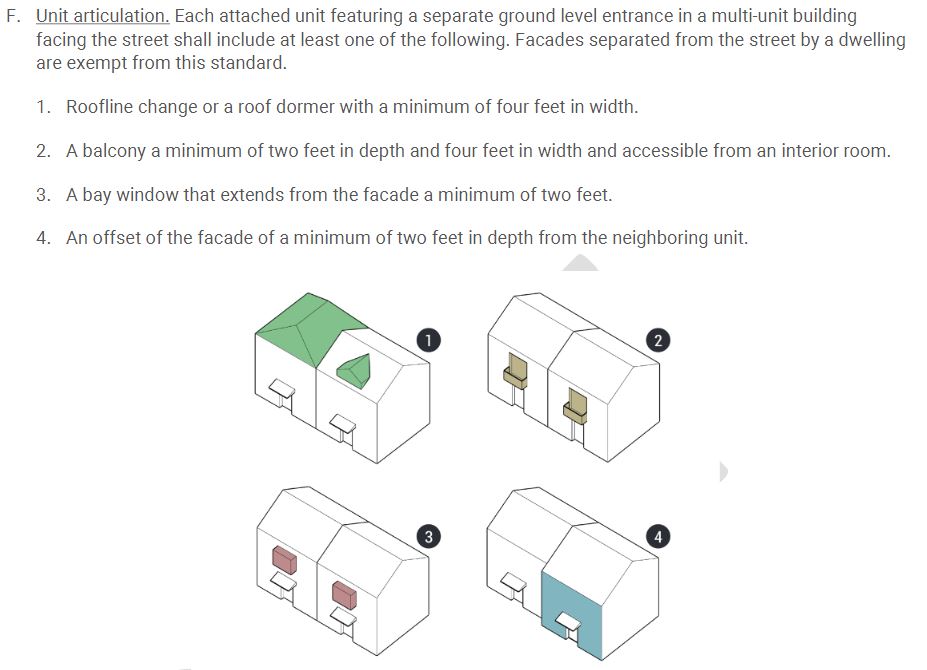

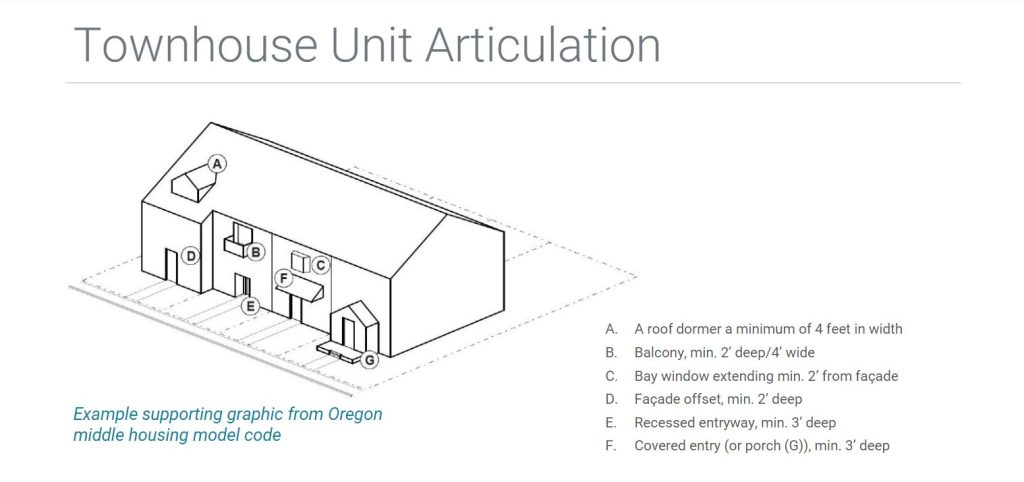

Micromanaged aesthetic requirements

Even worse than the efforts to shrink the buildings with FAR mandates, the model code requires each unit be “distinct” from one another with architectural detailing for no apparent reason. Is this bill about creating housing or highlighting the subtlety of unit count that will be barely noticeable to a neighbor strolling by? What does a roof slope, dormer, or bay window contribute to the housing solution? Nothing. Why should we be focusing our housing efforts on these vagaries of aesthetics?

The aesthetic mandates will only increase building costs, add embodied emissions to the design, and make the compliance review harder and longer with planners dimensioning roof slopes and balcony depths to determine approvals.

Architects don’t need a planning consultant to show them their bad ideas for building design. Additionally, why are we wasting any time whatsoever on this when the plan is to add homes, not govern what they look like?

Planners should be focused on making the rules simple for reviewers to understand to speed up approvals and get these projects built. We should be using flexibility to get as many homes and bedrooms as possible with a model code, not measuring balcony depths, dormer heights, and street-facing facade opacity.

Planners need to limit their purview to lot coverage, building setbacks, and maximum building heights. After that, just get out of the way and let the architects do their job instead of trying to do it for them. We don’t micromanage carpenters or roofers, extolling on them exactly how to hammer or shingle; we should give architects the same leeway to practice their craft without unreasonable stipulations.

Planners are missing the point with missing middle

We legalized missing middle homes to make housing development easier, to bring more homes on a lot, and to make our cities, towns and neighborhoods more equitable. We legalized missing middle homes so households of all types and sizes are offered sustainable solutions that reduce costs and give people housing options, not to regulate aesthetics and reduce the building’s size.

The other housing bill the state passed, House Bill 1293, is designed to streamline building approvals and outright banned design guidelines that reduced a building’s “height, bulk and scale” when it comes to housing. But these planners have cleverly realized that if those illegal reductions were codified with FAR limits and aesthetic requirements, they would meet legal compliance and totally undermine that bill as well.

All this backlash to the housing bills makes me wonder what these planning consultants fear most. With a six unit maximum, what is the worst that could happen without these proposed regulations on building size and aesthetics? Would the homes be bigger, and would it be cheaper and easier for households to find homes that fit their needs?

Oh, the horror!

The fight to legalize housing never stops

The restriction of housing didn’t stop when the Supreme Court invalidated racial covenants in 1948, it didn’t stop when redlining was banned in the 1960’s, and it won’t stop now that single-family zoning is at death’s door in the 2020’s. Housing restrictions always mutate and change into the next socially accepted regulation. By the time the Harrell administration finally releases its draft Comprehensive Plan, it will set the stage for housing here for the next 20 years. With it, they will likely adopt this model code with regulations that make homes smaller and more expensive to build.

There are more than 100 different ways to cook an egg. If we were in a hunger crisis, would people starving really care if the eggs were poached, scrambled or over easy? No, because they are starving. And that’s what happened with the model code. By micromanaging the flexibility to create the homes we need, we are missing the point of legalizing missing middle housing and are left with egg on our face when we try to cook up a solution.

The Washington State Department of Commerce is accepting public feedback on the model code until December 6. Please fill out this form and encourage others to do so. Tell them to raise FAR maximums or remove FAR restrictions entirely and to remove the high-cost aesthetic mandates from the baseline regulation.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.