Right now, the city of Seattle is at a crossroads. As a robust job market, the city has never had a housing plan that meets the demand. Thankfully, the Washington State Legislature has done a lot of work this spring, legalizing fourplexes everywhere in Seattle, and legalizing sixplexes near frequent transit. So, you may think we finally have the flexibility to have shovels hit the ground and start building much needed housing, but it’s still a little more complicated than that.

The law doesn’t change a city’s zoning code, it only tells the city how many homes are now legally permitted. It’s not a minimum, or a mandate, it’s simply the new threshold of what is allowed. For example, a lot that can build a sixplex can still build a single-family home, or some accessory dwellings units (ADU’s), or five townhomes, or some cottages, or even that sixplex which will soon be finally permitted.

This flexibility is to be woven into the city’s Comprehensive Plan, a once-a-decade planning process Seattle is currently working on, with a draft originally due in April, then June, and now pushed back to September with yet another delay.

City Planning staff seem reluctant to make big changes.

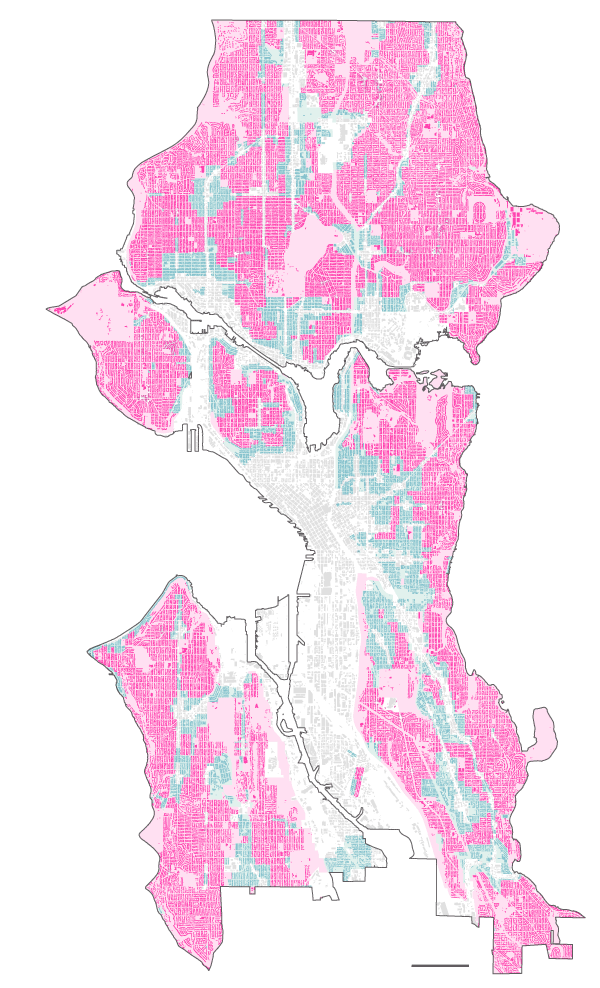

The problem is single family zoning, now called Neighborhood Residential zoning, does not meet the legal requirements under the new state law. It currently dominates the city’s landscape consuming about 29 square miles, meaning this change will be the biggest one proposed in the comprehensive plan. The zone will either be overhauled to meet compliance, or Seattle will have to choose one of their existing zoning types to meet the law. Seattle’s Low-rise zones are the first that meet the requirement and go the extra mile, but upzoning the city to one of these is a much bolder solution than planners have ever shown an appetite for.

Since the law has been publicly discussed for six months, with an obvious likelihood of it passing, and the city still wasn’t ready for it, there is clearly reluctance to go the extra mile. The draft plan was delayed because it doesn’t comply with this law. This means our planning staff has not looked at legalizing more homes throughout the city since it first explored doing so in 2015, and they certainly didn’t look to build in compliance with this year’s new law until the very last minute. With the final plan due in December, time is running out, and staff may desperately seek a consultant to deliver a template solution without adequate review.

Enter the Form-Based Code

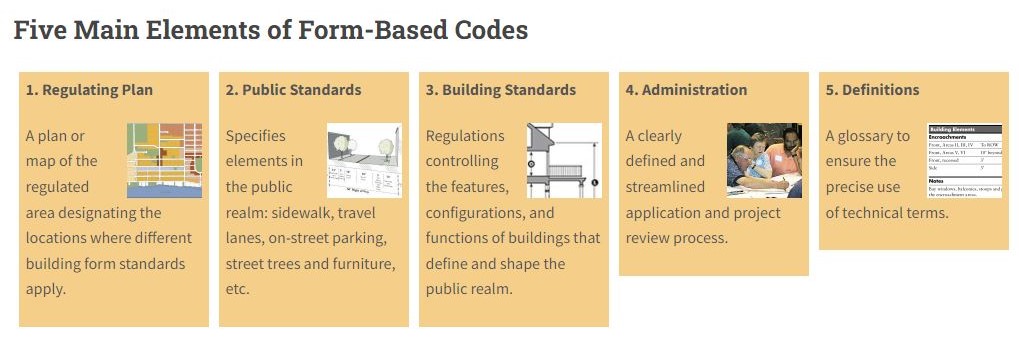

Seattle planners are now exploring something called a form-based code. The great thing about a form-based code is that it allows things like coffee shops, bookstores, corner stores, and small retail to mix in with the neighborhoods previously zoned exclusively for residential. With a form-based code’s flexibility for land-use, we can finally have vibrant, walkable neighborhoods again. We see this flexibility in places like Paris, London, Tokyo, New York City, or parts of Seattle where grandfathered-in uses were permitted before the invention of zoning, like the Central District, Capitol Hill, and Wallingford. Seattle planners are doing a great job exploring the flexibility of form-based code land use.

However, where a form-based code fails is when it is used to mandate aesthetic details that have little impact on improving the quality of the public realm—the very purpose of form-based code’s existence. This brings me to the other bill the State Legislature passed, one that will seek to streamline building approvals and get us away from legislating to subjective guidelines and mandating low-impact aesthetic details. If the subjective guidelines are ‘not ascertainable’ or if they reduce the building’s height, bulk, or scale beyond the zoning code, they are legally disregarded and no longer apply. But if your form-based code mandates building aesthetics, and reduces allowable height, bulk, and scale, it now is part of the code, and the guidelines meet the requirement of whatever ‘ascertainable’ means (is there a lawyer in the house?)

Prescriptive Design is part of form-based codes, which poses the problem.

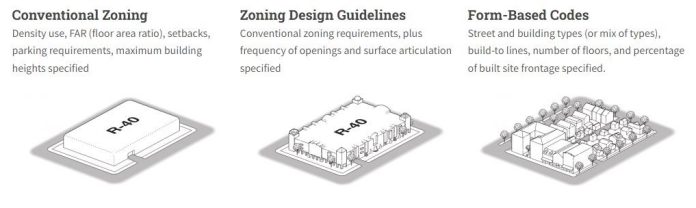

One of the five elements of form-based codes is to regulate building design, which can sound like it’s helpful in ensuring some baseline level of quality design in the public realm. However, form-based Codes are overly prescriptive and result in cookie-cutter designs that handcuff architects and discourage creativity. All the flexibility promised is now lost in prescriptive design.

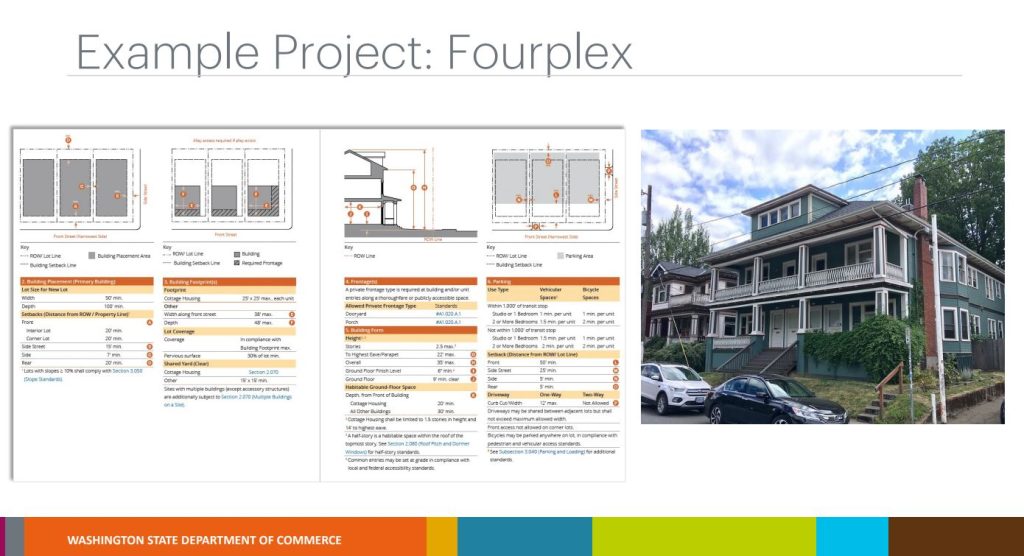

It will take out all design flexibility and force you to build something that looks like it came out of a catalog. For themed places like Disneyland, Leavenworth, and Seabrook Washington, form-based codes make sense. These are places that are master planned and sell the aesthetic as part of the vacation or town’s micromanaged feel. But in cities like Seattle, where we have a variety of property ownership, architectural styles, ages of buildings, and the city is not a manufactured vacation destination where everyone might feel like they should dress up in lederhosen, prescriptive design standards aren’t right.

The Washington State Department of Commerce’s exploration of form-based codes have already sounded the alarm bells for urbanists. The consultant who created this book sent the exact same one to other states too. With the clock running out on Seattle’s planning process, there is a deep concern that form-based code adoption will include prescriptive design regulations because it’s an established element of the code according to a consultant who has already completed a template.

City planners may think this is the easiest, most straightforward solution to get us into legal compliance with both laws, but the consultant’s arbitrary, prescriptive building design standards will decimate the entire effort. Seattle should be leading this effort, not relying on one consultant’s template, and adopt the portions we believe fit the goals of our city and discard the parts that make things like appealing design and affordability here worse.

Seattle is in a housing crisis, not an aesthetics crisis.

The eclectic mix of different styles of buildings is what makes Seattle neighborhoods interesting and desirable. Sure, you may have homes in your neighborhood you think look weird, aren’t what you’d want to build, or have too many materials or paint colors. But it’s not your house, and it is not just your neighborhood. We need to build homes, not fret over window frames, and roof slope details.

Those “ugly townhouses” that some elected officials and appointed city staff shake their head at in disgust, are precious to the people who call those places home. One person’s “ugly townhouse” is another person’s “dream home.” We don’t regulate what color you dye your hair or how loose or tight your pants are when you leave your house. Why should we regulate window sizes and whether your house has a flat roof or one with a pitch? Did I mention that Donald Trump loves prescriptive building design mandates? We need to celebrate change to neighborhoods and style, because if your neighborhood doesn’t change, it’s either deteriorating or skyrocketing further into unaffordability.

Planners need to let go and trust architects. We need new homes built citywide. Seattle is blessed with many talented architectural and construction firms, both big and small. But budgets are a real thing, and overcomplicating homes with ornamentation, dormers, and squiggly detail requirements are not going to make homes cheaper. A form-based code with overly specific design requirements will either make homes cost too much for most people to afford, or the cost to detail them means they’ll never get built at all.

How Seattle can reform housing instead of performing like they will.

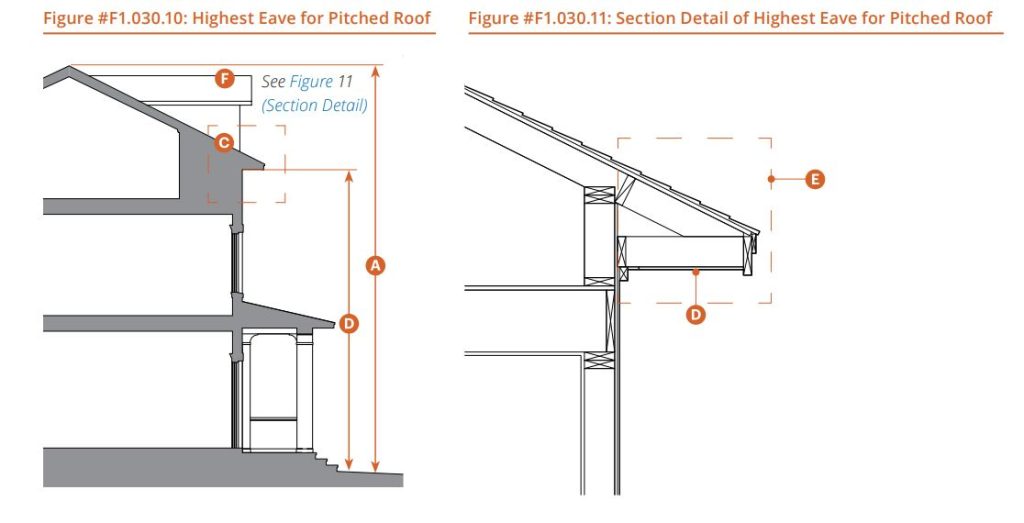

We say we want to be affordable, but we keep pushing everything to make housing more expensive. Complex buildings cost more to build, are not environmentally friendly, and make a passive house, mass timber buildings impossible to construct. If we adopt a form-based code, it needs to be simple and easy for planners to understand. Reviewing roof slopes, dormer heights, and cornice details yields no discernable public benefit and only adds to the delay of building homes. And remember, none of the century-old homes and neighborhoods that many adore today had to adhere to such subjective scrutiny from micromanaging city officials.

Let’s reduce every lot setback to three feet on all sides, legalize 50% lot coverage for the building footprint, and maintain a Neighborhood Residential zoning height of 30 feet. It would give you the flexibility to place your building or buildings across 85% of your site, meaning you can avoid knocking over that exceptional tree since there is plenty of room to work around it – by design. It will also give the residents enough space for a garden, a playground, or a communal Pickle Ball court. Today, architects spend too many hours ensuring their designs conform with overly specific code requirements instead of using their skill and design-thinking to find inventive ways to enhance the livability and sustainability of their projects.

By maintaining the height of neighborhoods with new development regulations, new buildings will fit in with their context. For example, a uniform allowable height of 30 feet is enough height to get rowhouses, stacked flats, or a combination of things in a comfortable family-sized home — and still allows for large-scale detached homes if that’s what you want to build. It also gives you the option to throw the homes above the first level and leave that space for a small retail shop or workspace for the community to support, since planners are right in seeking form-based code’s flexibility on land-use.

We need fewer rules and better processes.

Seattle is not unaffordable just because we don’t build enough affordable housing. It’s unaffordable because we don’t build enough total housing to meet job growth, stabilize the housing market, keep existing homes affordable, and build subsidized housing so that everyone in every market sector has a home here.

Seattle is unaffordable due to restrictive zoning, subjective rules, community reviews, and long timelines. Those rules made housing growth illegal in most of our city and made places where it was permitted too costly or difficult to build affordably or ever get built at all. Since this cookbook catalog of design mandates will be expensive to build, a form-based code’s prescriptive design rules will only perpetuate these problems. And since housing is almost never a charity, the aesthetic rules will only kill building plans, limit housing supply, and segregate who can afford to move into the neighborhood. This will guarantee gentrification without demolition.

We can say we don’t want our neighborhoods to change, but they always do and always have. People move in, they move out, they remodel their homes and gardens, they grow up, and they die. While a building may stay the same as you remember, the people living in it probably haven’t, and in Seattle’s ever increasing real estate market, the economics of your neighborhood have certainly changed.

A code to make our neighborhoods affordable again

We need to realize this is about people and not buildings. We don’t intend to ban people from living in our neighborhoods and to make sure we don’t, we need to relax the rules for housing. Everyone knows someone who is living in more house than they need or cramped into a small unit — not because they want to live like that, but because they want to stay in their community and there simply aren’t enough different types of housing options for people to choose from as their needs change.

Form-based codes can be useful for relaxing land use regulations. But overly prescriptive design standards are stricter and more exclusionary than the code we have, it just puts all the problems of segregation and housing affordability behind a pretty picture of something that’s never getting built anyway.

The flexibilities promised in form-based codes are great for mixing different uses within our exclusively residential neighborhoods. But legislating cornice details is bad form for Seattle and completely off-base. If we are going to adopt a form-based code, we need one that eliminates silly rules and celebrates our freedom of speech when it comes to identity, diversity, and that allows our neighborhoods the freedom to grow again. Isn’t that the city we want to be? Then let our buildings celebrate their diversity and let’s legalize architectural free speech in the process.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.