City staff proposed adjusting Issaquah’s inclusionary zoning program to encourage housing, but Tola Marts was not interested.

Humans are multiplying like rabbits in the Issaquah Valley, and frankly, Issaquah Councilmember Tola Marts has had enough. He’s ready to tamp down the population, and for Issaquah that means keeping restrictive fees on homebuilders in place, forcing humans to seek refuge in other corners of the region.

As his colleagues weighed the pros and cons of a pilot program proposing a minor adjustment to homebuilder fees and incentives in order to encourage development in Central Issaquah at a council meeting on Monday, Marts boldly suggested they were wasting their time.

“I want to gently poke at the underlying narrative that there’s anything wrong that we have to fix here,” Marts said. “So, we had so much development in 2016, we put a moratorium in place. And we had a moratorium in place for two years because housing was growing like rabbits in our valley.”

As he got warmed up in his degrowth manifesto, Marts also shared his frustration with statewide missing middle housing reforms spearheaded by Olympia Representative Jessica Bateman.

“And thanks to our friends in Olympia, we’ve thrown open the barn door and now people can build all sorts of condos and duplexes up on the hillsides,” Marts said. “So we’ll get even more market rate that we will be unable to control. So I don’t want more market rate, but I’m willing to put up with more market rate, and we can get the workforce housing that we so desperately need.”

Marts blamed newer Issaquah residents for traffic congestion and said the City was “choking” on growth and had not built sufficient infrastructure to handle it.

“I think what’s critical to know here is that we — over the last 20 years — have built a radical amount of market-rate housing in this town,” Marts said. “I’m proud of what we did while we did it, but we are now choking on all the housing that we put in without the infrastructure to support that housing.”

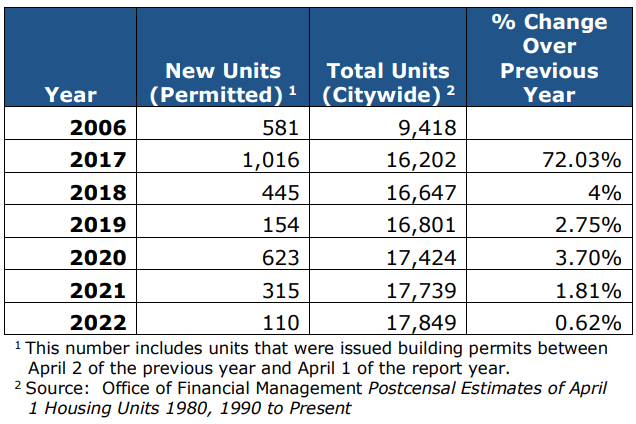

While Marts posited Issaquah was growing much too fast, City figures show housing growth had tanked in Central Issaquah, the city’s designated regional growth center, after the city implemented strict inclusionary zoning requirements, which at 12.5% were set significantly higher than even Seattle’s equivalent: the Mandatory Housing Affordability program.

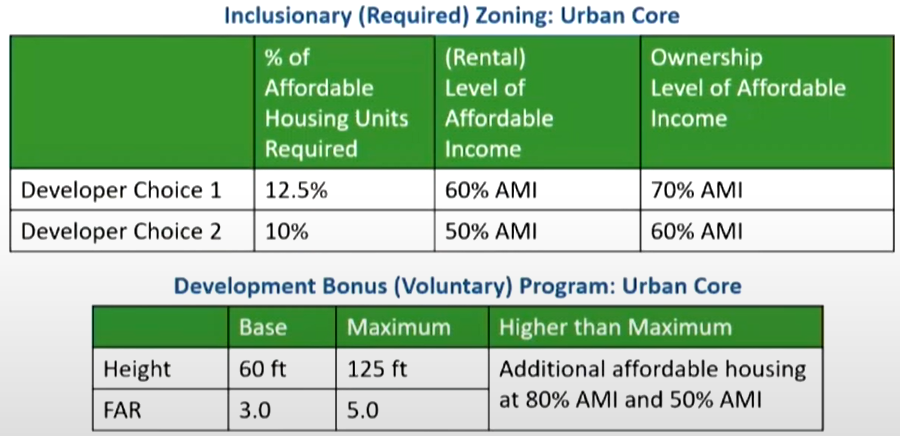

Central Issaquah’s inclusionary zoning requirements mean that if a developer built a 200-unit apartment building, 25 units would need to be set aside as affordable at 60% area median income. At reduced rents, the homebuilder ends up operating the affordable units at a loss, but the hope is the other units are profitable enough to make the whole enterprise worthwhile. However, given the added costs and the difficulty convincing banks and investors to invest in such an environment, most builders focused their energies on other cities.

Issaquah added just over 1,600 homes citywide from 2017 to 2022, but most of them were not in Central Issaquah which local leaders had intended to be the city’s growth center. Instead it has been the sprawl-ier Issaquah Highlands that has continued to be a focal point for growth.

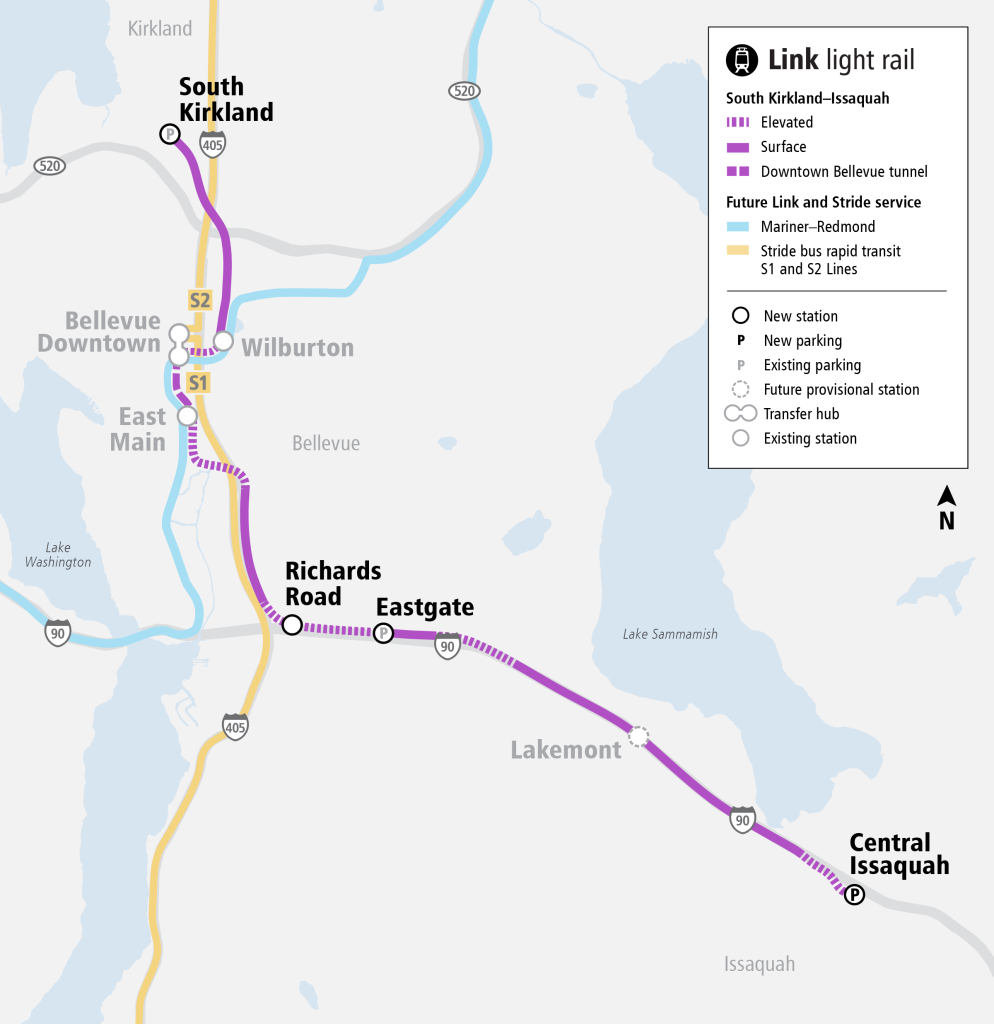

Nonetheless, it was the promise of robust growth in Central Issaquah that helped then-Mayor Fred Butler convince the Sound Transit board to add a light rail line with two stations in Issaquah and a direct link to downtown Bellevue. At the time, Kirkland was viewed as resistant to growth and Issaquah as embracing it. Thus Kirkland only got one station at the very edge of town, compared to Issaquah’s winning two stations, one near its city center.

Issaquah was growing quickly in the lead up to the Sound Transit 3 package assemblage and voter approval in 2016. But in September 2016, Issaquah passed a development moratorium — officially in the name of slowing suburban style-growth and shifting to a more urban character via new design standards. Issaquah lifted the citywide moratorium in 2017, but extended it in Central Issaquah to continue tinkering with affordability requirements and other standards. Even after the city council lifted two-year moratorium in Central Issaquah, few projects materialized, which builders have attributed to the inclusionary zoning requirements that went into place at the time.

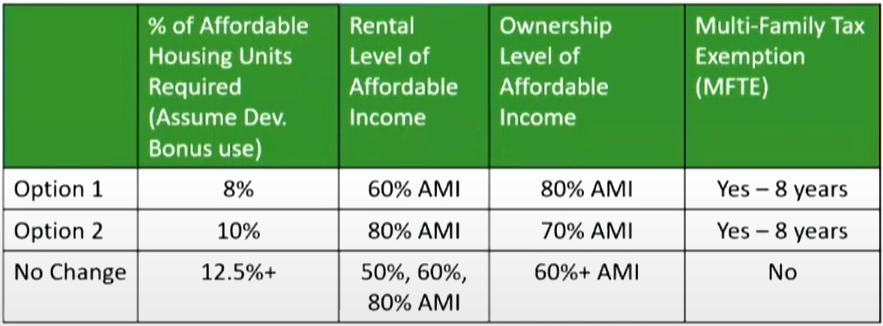

That’s where the “Pioneer Program” proposal that Issaquah City staff are crafting comes into play. The idea is to ratchet down the affordability requirements a tad in hopes of enticing a few mixed-use projects in Central Issaquah. The proposal also called for a eight-year Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE) to provide another incentive to build. Since inclusionary zoning requirement would tick down only a couple points to 10% at 80% of area median income, it’s a modest proposal.

However, Marts rejected the whole premise.

“So I don’t believe that residents are telling us to build more housing,” Marts said. “I believe residents are telling us we build too much market rate housing, and we didn’t recover the costs of the infrastructure associated with that market rate housing. So we have traffic and no ability to pay for things that will help manage that traffic. We built tons and tons and tons of housing in the valley already. That’s why we have low targets going forward because we blew out our numbers over the last 20 years.”

While Marts posited the usual ‘growth should pay for growth’ arguments typical of anti-housing homeowners, more anemic growth in Issaquah also robs the city of tax revenue from sources like the real estate excise tax and sales tax on builders. And of course there’s that old pledge to the rest of the region that Issaquah would build a dense urban neighborhood around its future light rail station on a line the region was invested billions of dollars in building.

While Marts assumes Issaquah residents are with him, polling shows strong support for expanding housing across the state. And many environmentalists would not agree with him that sustainability requires abandoning urban growth.

A four-term Councilmember first elected in 2009 and unopposed in his last three elections, Marts “chose to run for office to try to help his adopted community of Issaquah make the transition from being a growth community to one focusing on sustainability,” his council biography notes. (While Marts lives astride Squawk Mountain sandwiched between two massive parks and Tiger Mountain State Forest, people hoping to move to Issaquah to enjoy those amenities are just too late to the party — those pesky little rabbits.)

Marts argued it was premature to recalibrate Central Issaquah’s inclusionary program pointing to the disruption of the pandemic. However, that was misleading, since development activity has accelerated in some Puget Sound cities since the pandemic rather than slowing down. Seattle set a recent record in 2020 with more than 20,000 housing starts, as builders sought to take advantage of a streamlined online design review approval system.

Plus, housing prices show demand continues to be very strong. When Issaquah instituted its development moratorium in 2016, the city’s average single family home price was around $650,000 and the average condo sold for less than $300,000, according to Zillow estimates. Single family home prices have doubled since then, peaking at $1.4 million in 2022 and coming down slightly since then. Average condo prices peaked just shy of $550,000 during the pandemic. These price spikes are typical for the region and especially the Eastside, which has grown an increasingly exclusive enclave in recent years. People who were lucky enough to buy before the boom accrued incredible housing wealth.

No cities in the region are building enough housing to keep pace with demand, and unfortunately many are participating in a race to the bottom to see how little housing growth they can get away with. Some have gotten very sophisticated at disguising anti-housing policies in the trappings of progressive concerns, such as wanting new projects to immediately solve other ills, like traffic congestion, inadequate school funding, and the lack of affordable housing or reliable transit. Instead of an outright moratorium, loading potential housing projects up with fees and running them through a labyrinth of process will do.

Marts’ comments Monday were interesting for saying the quiet part aloud amidst the dog whistles. He sees less new housing as a virtue rather than a problem to solve.

That race to the bottom is exactly why a broad coalition of advocates came together behind Representative Bateman’s statewide missing middle housing reform. To people not lucky enough to already own a home, throwing “open the barn doors” doesn’t sound like such a bad idea.

Likewise, views seem mixed on Issaquah City Council and most of Marts’ colleague seemed open to the pioneer program to encourage more development in Central Issaquah. Contact the Issaquah City Council to let them know you want more housing in Issaquah, especially near the future light rail station.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.