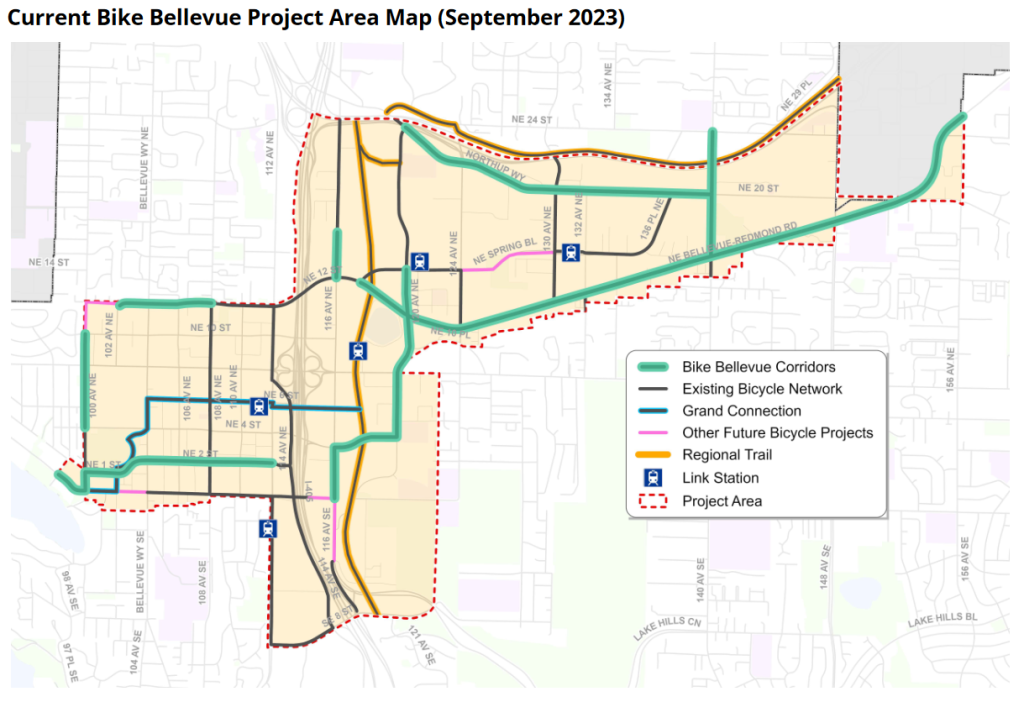

The City of Bellevue is pressing ahead with 15 miles of new on-street bike facilities across downtown, Wilburton, and Bel-Red over the coming years after the city council gave its go-ahead this past spring. The program, called Bike Bellevue, is attracting increased opposition from Bellevue residents and business interests who object to the modest reallocation of street space that it would entail.

Last week, the Bellevue Transportation Commission held a public hearing on the Bike Bellevue proposal, after the commission conducted a 90-minute “deep dive” with Bellevue city staff to dig into questions they had about the project, particularly related to the traffic modeling that the city has conducted. With a full buildout of the proposed network, Bellevue only expects to see a drop in vehicle speeds along the corridors in question of 0.2 miles per hour during the busiest time of day, while at the same time improving safety, and making some of Bellevue’s most pedestrian-and-bike-hostile streets accessible to a broader segment of users.

Bellevue has allocated only $4.5 million for Bike Bellevue, out of an expected $18.6 million budget needed to add or upgrade bike lanes on all 11 corridors in the network. The transportation commission is now tasked with making a recommendation to the City on where to prioritize the available funding, but that process, expected to run well into next year, is affording opportunity to relitigate the entire Bike Bellevue program.

In adding the proposed 15 miles of upgraded bike facilities, Bellevue would only be converting around 30 on-street parking stalls and reallocating around six miles of vehicle lanes — out of over 1,100 lane miles in the entire city.

Ahead of the meeting, Bike Bellevue’s opponents tried to frame the feedback the city’s received already as being disproportionately influenced by transportation advocates from outside Bellevue, primarily Seattle. An ethics complaint filed on December 4 against Bellevue’s Mobility Planning and Solutions Manager, Franz Loewenherz, alleges that Loewenherz conducted a “biased, covert and selective” campaign to undermine Bike Bellevue by contacting advocacy organizations that would be more tapped into the street users that Bike Bellevue is meant to serve, including Cascade Bicycle Club and Seattle Bike Blog, and providing public records that included talking points being used to oppose the plan. The complaint was amplified by right-leaning news outlets, like the anti-tax The Center Square, during the days leading up to the hearing.

But in-person, comment was heavily tilted toward people who would benefit from the modest upgrades that Bellevue would bring.

“You may be hearing from others today about how Bike Bellevue doesn’t work for families, but in fact it is the complete opposite,” Bridle Trails resident Ed Wang told the commission. “It is our current transportation system, based solely on cars, which fundamentally fails the needs of our families. Bike Bellevue would significantly improve the lives of children, like my son, and parents, like myself.”

“I would love safer streets to walk on, and I think bike lanes would greatly contribute to this, so I 100% support Bike Bellevue,” Christina Hwong, a resident of Old Bellevue, said, noting the benefits that could come for people who aren’t even using a bike. “We should have streets that are designed for people to drive safely instead of telling people to drive slower.”

“I am 100% in favor of the Bike Bellevue project,” John Chelminiak, who served on the Bellevue City Council for 16 years until 2019, told the commission. “I think the Bel-Red repurposing is a very good project from what I’ve looked at, and I do want you to know that I am not now, nor have I ever been, a Seattle bicycle activist.”

Kelli Refer, executive director of Move Redmond, emphasized the need for cross-jurisdictional coordination to prevent a situation where bike lanes being added to Bel-Red Road in Redmond fail to continue across the border into Bellevue, and noted the importance of enabling multimodal access between coming light rail stations.

“There is not enough parking at light rail stations to have everyone drive and park there. Bike Bellevue is an essential component of transit access,” Refer said. “This is a smart investment that will pay dividends not only in having safer streets for all users, but it will also ensure that we have a healthier more accessible community for the one in four Washingtonians who do not drive.”

Neighbors for a Livable Bellevue, a community group that opposed the establishment of a transportation benefit district in Bellevue earlier this year to increase transportation funding in the city, set up a form letter on their website, enabling written public comments ahead of the meeting to come in heavily in opposition to Bike Bellevue. “I urge you to reject Bike Bellevue projects in their current form and advocate for more cost-effective and safe alternatives that do not require taking vehicular lanes from the majority of the traveling public,” the form letter stated.

Opponents of Bike Bellevue have a tough case to make as they argue that the current quantity of vehicle capacity on Bellevue’s streets is the only way to accommodate the 33,000 additional residents and 67,000 new jobs expected in the city’s core neighborhoods by 2035 –and that leaving the overbuilt roads to fill up with vehicles is preferable to providing Bellevue residents, workers, and visitors alternative options for getting around.

Bike Bellevue Likely Doesn’t Go Far Enough

Most of the expected increase in bike trips in Bellevue’s urban core neighborhoods over the coming years is expected to come from the change in land use toward more high-density uses, and less from the installation of Bike Bellevue’s infrastructure itself. The bike lanes planned as part of the program are expected to lead to a modest 7% increase in bike usage in the corridor, making it clear that the Bike Bellevue investments are really more of a baseline level of improvements, which is demonstrated by looking at the design of some of the corridor plans.

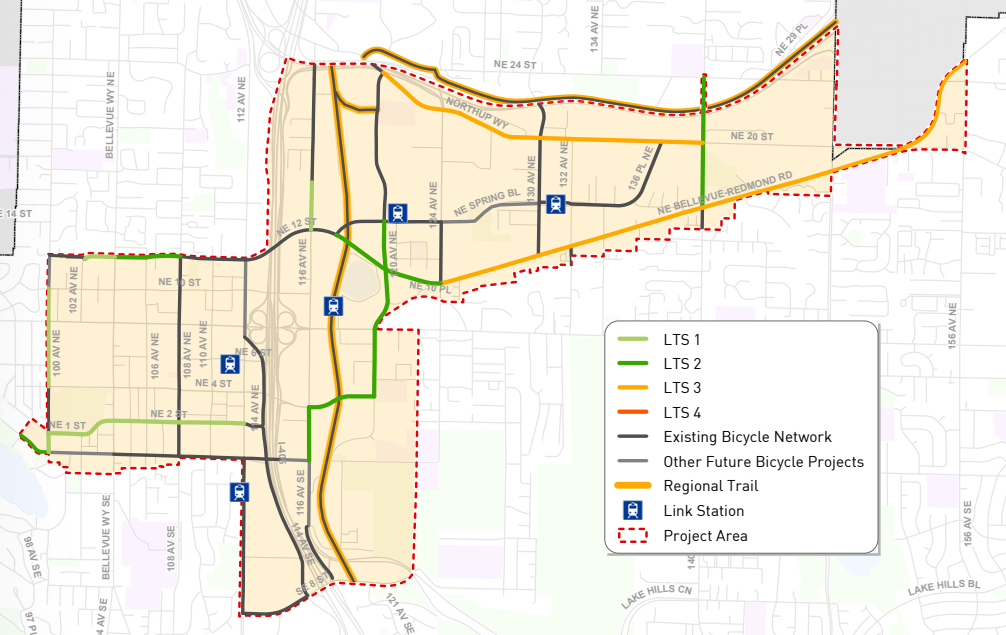

Using a “level of traffic stress” metric, Bellevue determined which streets to upgrade based on current conditions for people biking and the potential to create a fully connected network in these three neighborhoods. A majority of the bike facilities that exist are a level of traffic stress 4, meaning only people biking who are most comfortable sharing street space with fast-moving cars are able to use them, with around one-third of the miles in place a level of stress 3, accessible to slightly less bold users.

If all of the Bike Bellevue corridors were upgraded, level of stress 3 would be the new baseline, with over half of the facilities in the area improved to a level of traffic stress 1 or 2, meaning the network would be more welcoming to people who have much less experience and confidence on bikes, but half the network would still be only accessible to enthused and confident people.

Bel-Red Road, one of the most important corridor upgrades included in the plan, would retain its 35-mph speed limit and four lanes of fast-moving traffic, with no physical barrier planned to separate people biking from that roadway. The plan to create space for people to bike on the street is a huge step, but not the final one. The same is true for Northup Way, despite the ample street space and potential as a direct connection to the 520 Trail. The City of Bellevue recently celebrated the completion of a new bridge connecting the 520 Trail and Eastrail, but the street has a long way to go before it would be safe for all ages and abilities. But Bike Bellevue is a well-planned start.

In the end, it won’t be a computer model spitting out a future amount of traffic delay that decides whether Bike Bellevue aligns with the vision Bellevue’s leaders have for the city. By laying out the case so meticulously in its Bike Bellevue plan, city staff have laid the groundwork for Bellevue’s policymakers to be able to decide what type of future they’d like to create.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.