A new CEO can’t move mountains; board reform is needed.

For the second time in two years, Sound Transit is seeking a new CEO following Julie Timm’s departure — and is doing so amidst its worst financial crisis since the turn of the century.

A new CEO will not solve Sound Transit’s growing woes all by themselves. The agency’s growing problems increasingly stem from the failures of the agency’s board of directors. Composed of elected officials for whom Sound Transit is a secondary or tertiary responsibility, the board lacks investment in the success of the system. They have made a series of decisions that have caused significant delays, higher costs, and threaten future ridership.

As Sound Transit seeks a new CEO, it’s time for transit riders and environmental advocates to begin exploring options for significant reforms of the Sound Transit board in order to help solve its current problems and get system expansion back on track.

Julie Timm’s departure comes two years after the Sound Transit board voted not to renew then-CEO Peter Rogoff’s contract. Rogoff had been found to have created an unsafe workplace, especially in his treatment of female employees. His tenure also saw mismanagement of key projects, including problems with concrete plinths on the East Link segment over I-90 that have delayed opening of the segment by at least two years.

Timm was brought on to help correct these problems and help get system expansion back on track. Timm regularly rode Sound Transit’s buses and trains and rightly made improving the rider experience a high priority.

Unfortunately, Timm was unable to address deeper challenges facing the agency. One of the biggest is rising construction costs that threaten to cause even more delays in system expansion. Just last week, Sound Transit revealed cost estimates for a Federal Way maintenance base have risen by as much as $1 billion due to wider inflation in the construction industry.

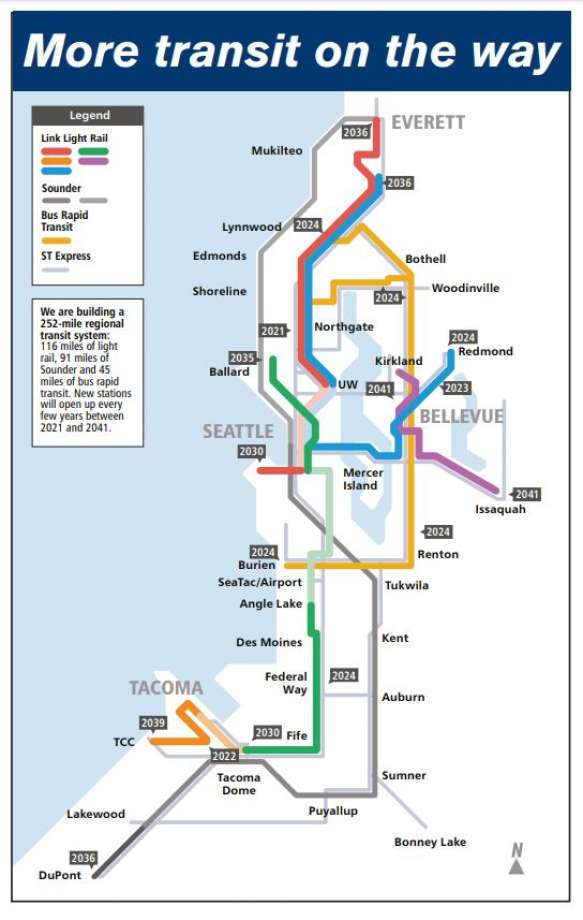

Seven years after voters approved Sound Transit 3 (ST3), key routes such as the West Seattle and Ballard lines remain mired in planning and study, with boardmembers regularly meddling in pivotal decisions. With each delay comes rising costs for further studies and, ultimately, rising construction costs.

Although a new CEO will be asked to tackle these challenges, they will struggle to do so without a change in direction from – and perhaps in the composition of – Sound Transit’s board of directors.

The Sound Transit board is currently made up of 17 locally elected officials plus the secretary of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), currently Roger Millar. The county executives for Snohomish, King, and Pierce counties hold three of the Sound Transit boardmember positions and they in turn appoint the remaining 14 members from county and city councils within the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) that comprises Sound Transit. The appointments are generally weighted for population, giving King County significantly more representation on the board than Snohomish or Pierce counties.

Most local elected officials are serving in a part-time capacity with limited staff support in their primary office — the Seattle City Council and King County Council are some of the few exceptions. This means that for the majority of members appointed to the Sound Transit board, overseeing the transit agency is a part-time job within a part-time job.

Another five members do have videos on and appear to be actively listening from afar. Other nine boardmembers have videos off or are absent in Seattle CM Juarez's case.

— The Urbanist (@UrbanistOrg) December 15, 2023

Not only do these appointees lack extensive experience with transportation policy when appointed to the board — few board members regularly ride Sound Transit’s services. As a result, many boardmembers simply do not have the time, expertise, or familiarity with the system for which they make major policy decisions. For most, Sound Transit duties do not factor heavily in their re-election prospects, providing another incentive to focus attention elsewhere.

The result is a board that has made a series of bad decisions that undermine the effectiveness of the system and make the CEO’s job much more difficult. Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell and King County Executive Dow Constantine spent much of 2022 and 2023 pushing the other Sound Transit boardmembers to change the location of the new Chinatown-International District station that would be built as part of ST3. The new locations, north and south of the neighborhood’s existing station at 5th Avenue S and Jackson Street, undermine transfers within the system and would likely reduce overall ridership.

Under pressure from Vulcan and Amazon, the Sound Transit board is risking further delay of final environmental approvals for the Ballard Link in order to conduct additional study on moving the planned South Lake Union station, potentially to locations that would have less ridership. The board also just approved a $3 flat fare that is unfriendly to the system’s frequent riders in the urban core and is unpopular with existing riders.

Sound Transit’s Technical Advisory Group has also called out the agency for failing to move quickly to implement its recommendations, many of which aimed to reduce board micromanagement.

Taken together, these factors along with Timm’s quick ouster after just 16 months on the job suggest that the Sound Transit board is part of the agency’s problems. Without a change in direction or reforms to the board, they are setting a new CEO up for failure.

One of the CEO’s main jobs under the current structure is managing relationships with 17 local elected officials. Rogoff and Timm appear to not have succeeded at this, likely for different reasons. This aspect of the job may effectively limit who would want to serve as CEO and their ability to navigate Sound Transit successfully through its current challenges.

Notably, Sound Transit’s most effective CEO brought deep experience in local government to the job. Before Joni Earl was appointed CEO in 2001, she had served as city manager of Mill Creek and as deputy executive for Snohomish County. This experience and her relationships with local elected officials helped to corral them into supporting her reforms that put Sound Transit back on stable financial footing and delivered her revised light rail plan on time and under budget. However, it does not make sense for the pool of potentially effective CEOs to be limited to the ranks of local government managers.

Before considering changing how Sound Transit board members are chosen, transit advocates should first seek to change who is chosen to be a board member. Appointees such as King County Councilmember Pete von Reichbauer, Auburn Mayor Nancy Backus, and Kenmore City Councilmember David Baker are examples of local elected officials for whom mass transit does not appear a high priority.

Several current board members are leaving elected office, including Baker, as well as Seattle City Councilmember Debora Juarez and King County Councilmember Joe McDermott. These departures create an opportunity for King County Executive Dow Constantine to appoint new board members who have a deeper commitment to Sound Transit’s success and the needs of its riders. The ranks of city councils in King County are increasingly full of Sound Transit supporters and regular transit riders who deserve a chance to help guide the agency through its present challenges.

Still, it’s worth considering whether there are other governance models that could help improve Sound Transit and avoid the known pitfalls of county executives appointing board members. One possible reform is to directly elect Sound Transit’s board and make it a full-time paid position.

It’s been done before. The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) has nine boardmembers, each of whom are directly elected by a public vote from nine districts of equal population size across the BART district. A similar model could be used to divide up Sound Transit’s RTA into nine or so districts of equal population size, each of which would elect a director to the Sound Transit board. This would ensure that board directors are directly accountable to voters for the state of the system, and would likely increase the chances that rider-friendly people serve on the board and can give the job their full attention.

For the last 20 years, it has been conservative voices such as the Washington Policy Center that have led the call for an elected board, hoping that voters would elect anti-rail boardmembers to rein in the system’s growth. Their advocacy has led transit supporters to be skeptical of an elected board, but that skepticism is unwarranted.

Conservatives are likely to be disappointed by the outcome of an elected board. Given the widespread popularity of mass transit in the RTA, it seems much more likely that an elected board would be composed of transit supporters and rail advocates. That’s the case for the BART board in the San Francisco Bay Area, where directly elected boardmembers are usually transit riders who have emphasized improving the rider experience. BART’s current financial woes are not the fault of that elected board, given the system’s over-dependence on fares and the lack of state operating funds.

There are other options for reforming Sound Transit’s board. An incremental approach could include appointing members who represent riders, and members who have technical expertise with project management, finances, or engineering.

Another option that would be more transformative would be abolishing the board entirely and moving the agency under WSDOT, which has experience managing and delivering major transportation infrastructure projects, and could be more insulated from efforts by localities to thwart station locations or route decisions. WSDOT’s Millar has been one of the most reform-minded members of the Sound Transit board.

However, moving ST under WSDOT would also put the agency at the mercy of whoever succeeds Jay Inslee as governor. There is no guarantee that the next governor would appoint a transit champion to lead WSDOT. Republican Dave Reichert currently holds a narrow lead over Democrat Bob Ferguson in polling for the 2024 gubernatorial election, running the risk of a conservative appointee being named to lead WSDOT in 2025 who would not be good for Sound Transit. Finally, WSDOT’s own record in supporting the passenger rail program it does oversee, the Amtrak Cascades, is seen by many transit advocates to be mixed at best.

As long as Sound Transit’s CEO must respond to the desires of 17 local elected officials, most of whom do not treat Sound Transit as a priority and lack the expertise and resources needed to oversee the agency effectively, they will struggle to tackle the agency’s problems. Transit advocates need to begin making reform of the Sound Transit board part of our overall agenda if we’re going to realize the rapid transit projects we so urgently need in this region.

Robert Cruickshank

Robert is the Director of Digital Strategy at California YIMBY and Chair of Sierra Club Seattle. A long time communications and political strategist, he was Senior Communications Advisor to Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn from 2011-2013.