Protests that recently shut down I-5 have reignited a debate that goes back to the freeway’s beginning.

Complicating the narrative of critics who believe major American thoroughfares should remain free of protest is the inconvenient fact that Interstate 5 was steeped in it from the beginning.

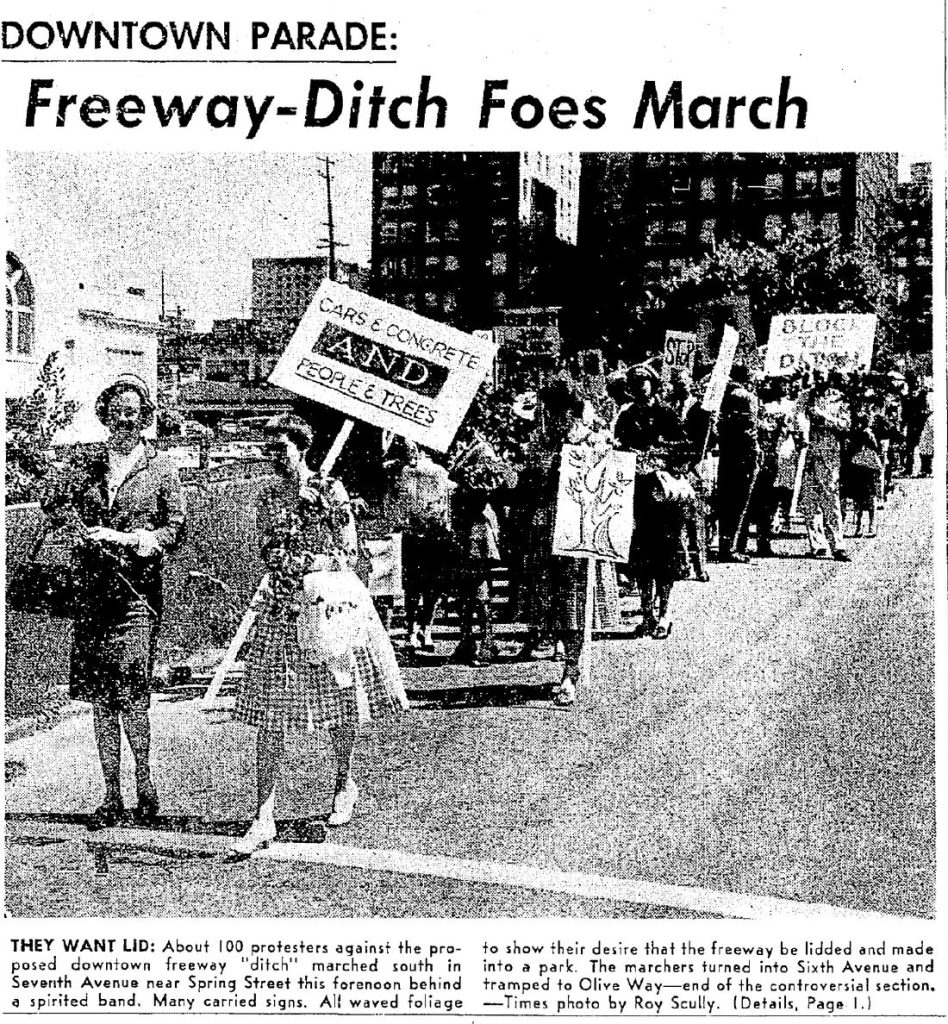

A few years after President Dwight Eisenhower authorized the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act in 1956, a group of 100 marchers – nearly all of them women – took to the streets to push back in June 1961. Some feared that the future freeway would cut area hospitals off from the rest of the city; others lamented pollution and the car-caused ruination of Seattle’s pristine natural environment.

Along a strip of road soon to be occupied by Interstate 5, sign-wavers with placards reading “Tree Lovers Arise” and “Keep Seattle Beautiful” urged transportation officials to at least lid the new freeway if they had to build it at all. The direct action of these White Seattle women eventually proved partly successful.

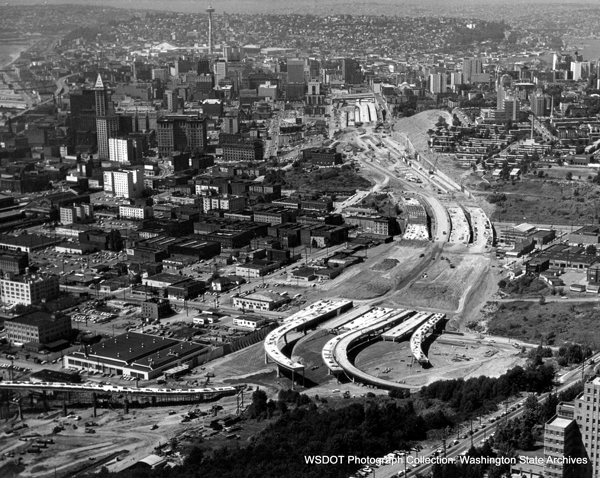

Interstate 5 opened piece-by-piece, up and down Puget Sound in the 1960s, cutting through the heart of the city, razing thousands of homes, displacing droves of city dwellers. No sooner had the expressway opened than did it become clogged with cars: when the stretch of Interstate 5 linking Everett and Seattle opened on February 3, 1965, 20 policemen were posted on freeway access routes to mitigate traffic jams. But thanks to the neighborhood activism of recalcitrant women, residents of First Hill were soon immunized against the worst impacts of Seattle’s new interstate.

Built atop a brutalist lid, the concrete-laden Freeway Park opened over I-5 on July 4, 1976, and was named after local transit activist Jim Ellis. “There are dozens of cities in the United States where freeways run through land of high value,” said the park’s namesake at its opening ceremony; “these cities could create a magnificent new environment by decking freeways.”

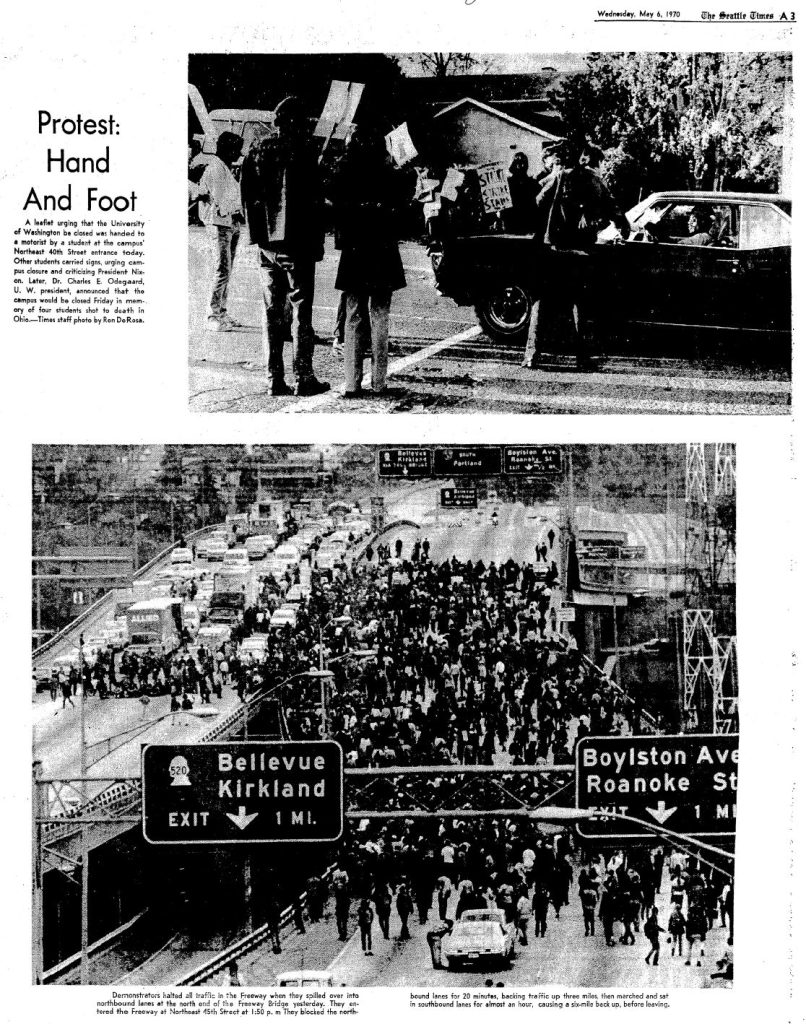

By the time Freeway Park opened on the bicentennial of the United States, many Seattleites were in no mood for national chauvinism. The death toll of the Vietnam War was still raw; a few years earlier, Interstate 5 hosted a massive demonstration against it. On May 5, 1970, approximately 7,000 antiwar protestors marched onto the 45th Street I-5 on-ramp near the University of Washington. Galvanized by the Kent State massacre and undeterred by patrolmen brandishing billy clubs, the marchers blocked traffic in both directions for 80 minutes, causing a backup stretching more than 200 blocks.

“That was an eerie feeling, marching down the freeway,” wrote Frank Herbert, Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist and author of the 1965 science fiction novel Dune; “People waved and gave victory signs from cars stopped by the march. At one point, a row of trucks honked their horns in cadence with the marchers’ chanting.”

What stands out in contemporary press coverage of the anti-freeway demonstrations on First Hill versus the anti-war protests on the freeway is the fact that one was made to look rather like a picnic, while the other was framed as the beginning of the end for Western civ. When women from relatively affluent First Hill picketed against the freeway on June 1, 1961, Seattle newspapers delighted in the spectacle, describing the snazzy midcentury sartorial choices of high-heeled women marching to protect their backyards. Backed by a four-piece marching band blaring “When The Saints Go Marching In,” the ladies of First Hill also enjoyed a police escort.

The Seattle Times referred to the White women’s freeway march – a demonstration – as a “parade.” The paper echoed the environmental concerns of Seattle’s original freeway protesters. When a 1961 state law against billboard clutter on Interstate 5 was nearly diluted, the paper sounded the alarm: “The new stretch of freeway offers vistas of lakes, mountains, and trees. Motorists who appreciate the scarcity of sign clutter should urge legislators to resist the pressures of the billboard lobby.” Yet when the subject of freeway protest turned to antiwar a decade later, the mood of Seattle media shifted.

“The necessity is to halt the spiral of violence,” thundered the Seattle Times editorial board after the peaceful Vietnam War protest of May 1970; “this won’t be done with the cooperation of the far-left agitators whose immediate demand is withdrawal of United States forces from Vietnam, but whose ultimate goal is destruction of the American system they despise.”

Conspicuously absent from the Times during the 1961 White women’s freeway protest was any diatribe about the possible demise of the republic. But what could be more ‘anti-American’ than a demonstration against an expressway?

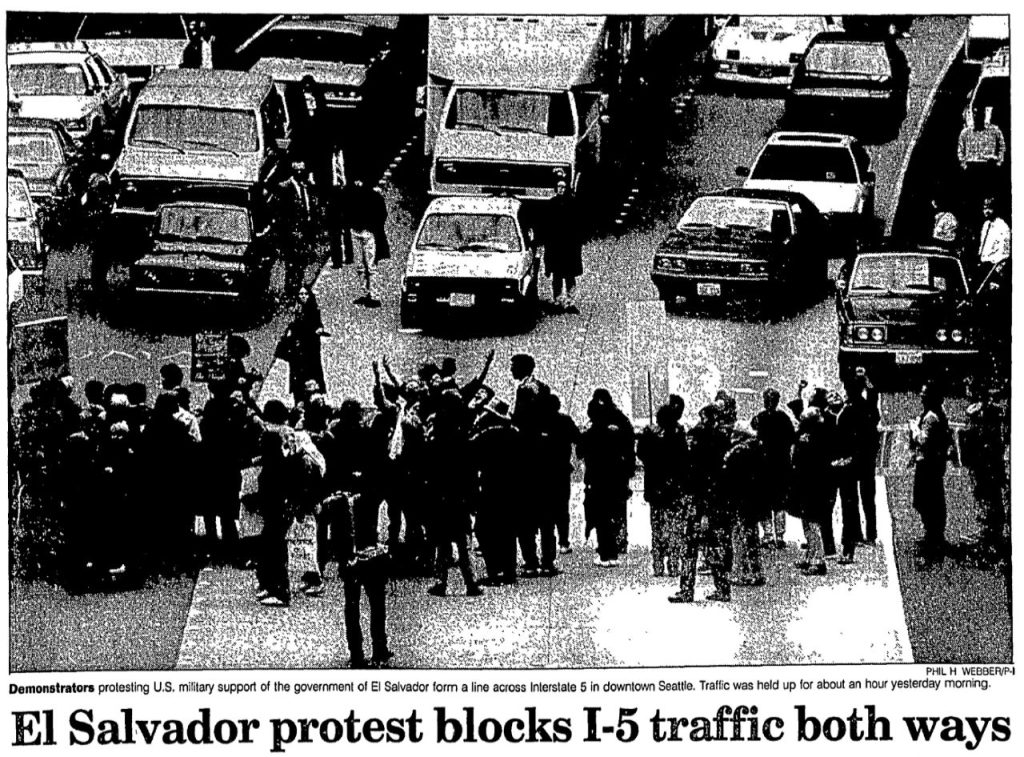

For Seattle freeway protesters, perhaps the difference between public support and public scrutiny was a friendly-seeming face. After six Jesuit priests were murdered by the U.S.-backed Salvadoran Army in November of 1989, protests broke out around the world, denouncing America’s brutal puppet regime in El Salvador. Demonstrators urged a ceasefire. In Seattle, on November 20, 1989, police arrested 72 protestors who obstructed traffic on Interstate 5 near the Freeway Park established by activists a generation earlier. Several of these demonstrators resisted arrest and engaged in petty property damage.

But the vandals weren’t an easy political target: the march was organized by Seattle churchgoers, and participants – many of them ministers – brandished wooden crosses. As God’s sheep led the first local freeway disturbance in decades, Seattle Times jeremiads about the fall of civilization were nowhere to be found.

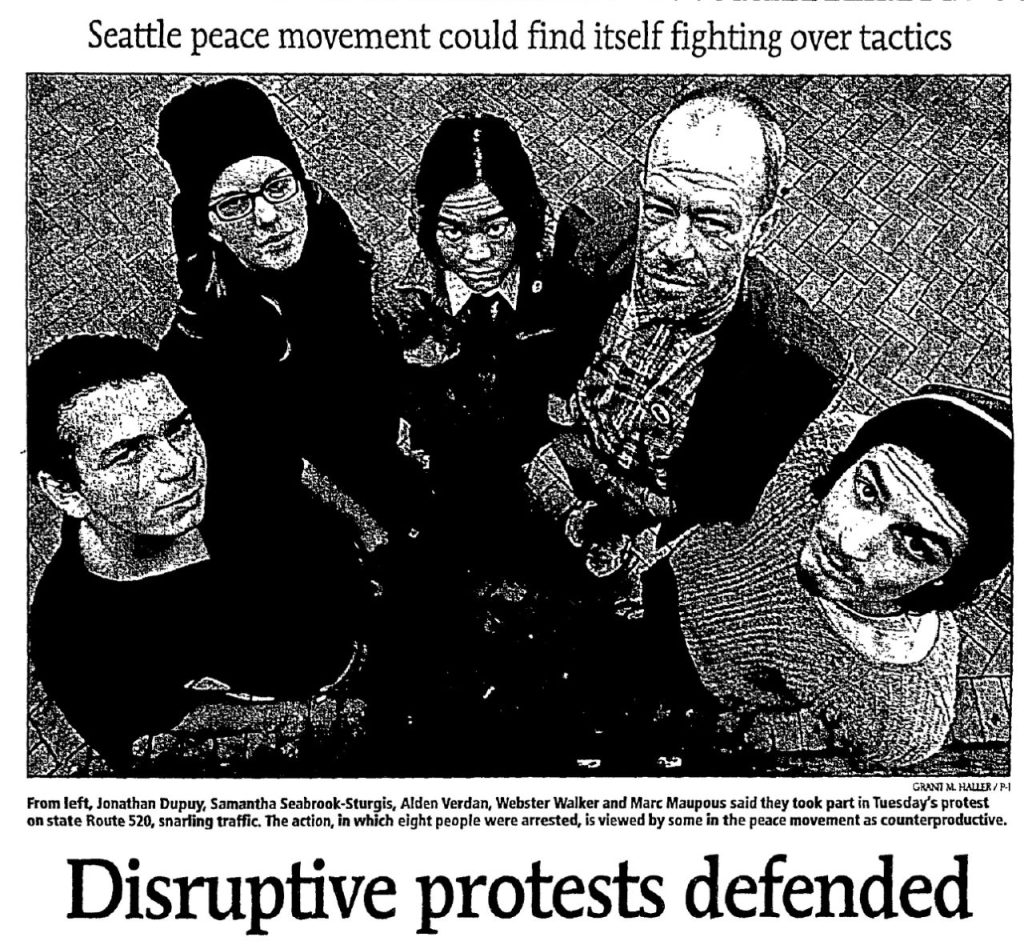

America’s post-9/11 moment presented area reactionaries with a more familiar freeway foe: young dissidents and brown immigrants. The coming Iraq War prompted protesters to block the east approach to the Evergreen Point Floating Bridge in February 2003. Represented in the crowd were teenagers with green hair, college students arrested for trespassing, and an immigration rights coordinator named Pramila Jayapal (thirteen years before she eventually became a Congressional representative). The coalition’s direct action caused local hand wringing about tactics and criminality, with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer bemoaning “calls for more disruptive protests in the future represent serious consequence for the Seattle peace movement.”

One 20-year-old participant responded to the criticism that protests disrupt public safety by saying “We’re not going to beg George Bush to stop the war. We’re going to put a wrench in the system to slow it down, to shut it down.”

The reason a freeway protest works as a political statement is because our politics already prop up freeways at every turn. Not everybody agrees these roads should exist, but everyone has to contend with their existence; residents displaced by their construction, neighbors who deal with noise and noxious fumes, environmentalists who see them as a disaster. A single affordable housing development or bike lane in a major city is subject to endless delays and red tape, design review and public discussion; by contrast, interstates and their itinerant connections go up willy-nilly, whether they’re welcome or not. So long as we take for granted that freeways belong in the hearts of our cities and at the center of our transit decisions, they’ll remain an effective target for protestors seeking to disrupt business as usual.

In countries with a greater tradition of social investment in public space, protests can take on a carnivalesque atmosphere that doesn’t detract from the seriousness of the statement made. That country is not the United States, where pedestrian gathering spaces are surrounded by cars, and expressways exist in place of greenways. Not coincidentally, some of the most recent episodes of Seattle freeway protests involved intersections between one form of preventable public death – police violence – and another (pedestrian fatalities).

As Black Lives Matter activists took to Interstate 5 to call for divestment from the Seattle Police Department, activist Summer Taylor was struck and killed by a speeding driver traveling the wrong way onto Interstate 5 in July 2020. With calls for increased police accountability still roiling in January 2023, a Seattle cop traveling at freeway speeds on a local road struck and killed Jaahnavi Kandula at a marked crosswalk. Every freeway protest would seem to have two targets: the progressive cause at hand – anti-police brutality, solidarity with Palestine – and also the status quo that makes disruption of car traffic a great societal disturbance.

Everywhere we look, places to protest are drying up. Tech titans are canceling social media as a space for insurgent activity, turning Twitter into a vapid fascist-friendly platform and Facebook into a torrent for fake news. Lacking the moral fortitude required to stand against a genocide in Gaza, higher-ups at American universities are cracking down on pro-Palestinian organizers. Nationwide, lawmakers are targeting freeway protest: a bill to this end has already been introduced in the Washington State Legislature. But the proposed laws are a step behind the movements they’re intended to stop.

The crises of late-stage capitalism are many: exclusionary cities, erratic weather caused by climate change, and endless war. As the costs of this condition escalate, so will desperate protests against them.

“The most disciplined revolutions have relied upon mass action,” writes Vincent Bevins in the 2023 book If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution; “It is conceivable that the 2020s will surpass the 2010s as the decade with the most protests in human history.”

Protest is a way of life now, and Interstate 5 was born in it. The traffic will eventually clear; and if it doesn’t, you were used to it anyway.

A full list of newspaper archives cited in this article is available here.

Shaun Scott is the author of Heartbreak City: Seattle Sports and the Unmet Promise of Urban Progress, available now from University of Washington Press.

Shaun Scott

Shaun Scott is a Seattle writer. His book Heartbreak City is available wherever books are sold.